Rhode Island offers a great range of edible plants, even in small patches of overlooked land.

You might spot lamb’s quarters growing near a fence line or find wild strawberries nestled low to the ground in early summer. Japanese knotweed shoots, often treated as invasive, are actually edible and tangy when harvested young.

Many of these plants have been foraged for generations, used fresh or stored for later. Garlic mustard leaves have a bite similar to arugula, while stinging nettle loses its sting once cooked and delivers a rich, earthy flavor. Ripe elderberries hang in dark clusters, but only after the flowers have drawn pollinators through the spring.

The range of options is wider than most expect from a state this size. There’s no need to travel far to come across edible leaves, flowers, shoots, or roots. Once you begin to recognize a few of them, it becomes easier to head home with a surprising variety of fresh, foraged food.

What We Cover In This Article:

- The Edible Plants Found in the State

- Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

- How to Get the Best Results Foraging

- Where to Find Forageables in the State

- Peak Foraging Seasons

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

The Edible Plants Found in the State

Wild plants found across the state can add fresh, seasonal ingredients to your meals:

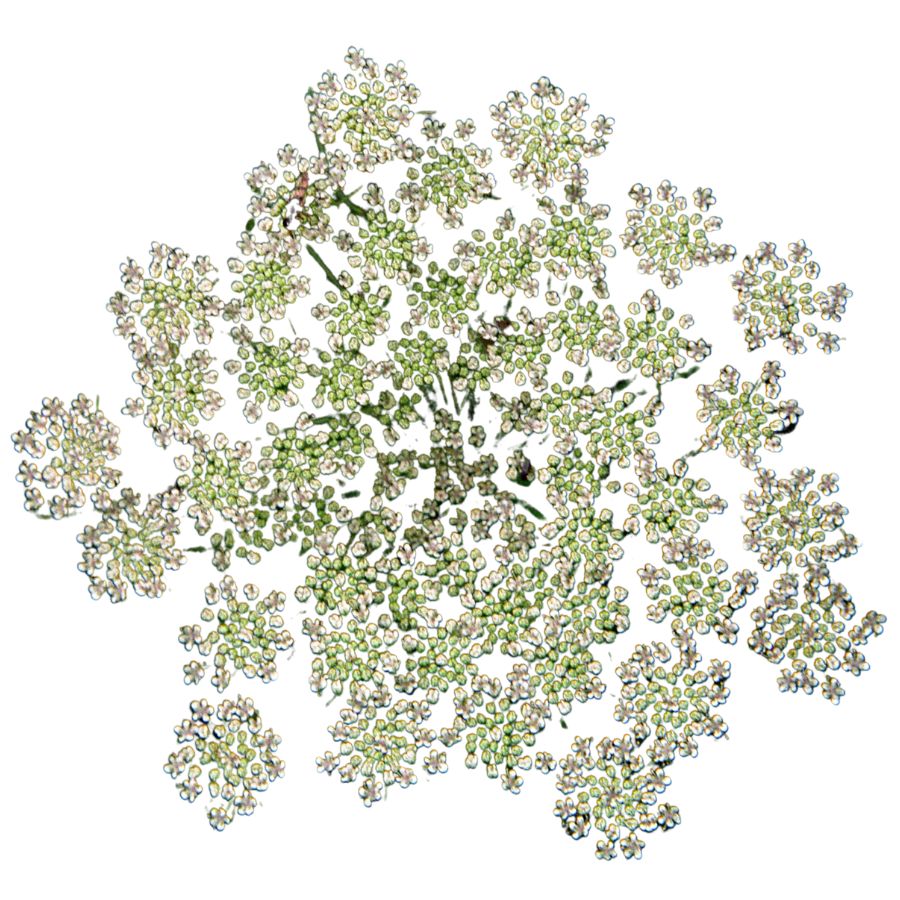

Common Plantain (Plantago major)

Common plantain has broad green leaves that grow in flat clusters, with stems that connect at the base and long, vertical flower spikes. You can tell it apart from similar plants by looking for those strong parallel veins and leafless flower stalks.

Its young leaves have a slightly earthy flavor, somewhat like spinach with a stringy bite. Most foragers blanch or fry them to take the edge off the toughness.

The seeds aren’t flavorful on their own, but you can dry and grind them for bulk or texture in flour mixes. They also release a mucilage when soaked, which can be useful in thickening recipes.

There’s no danger from the plant itself, but it’s smart to avoid spots where herbicides are used. Leaves and seeds are the most commonly eaten parts—skip the roots, they’re woody and offer little culinary value.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

Bright yellow flowers and jagged, deeply toothed leaves make dandelions easy to spot in open fields, lawns, and roadsides. You might also hear them called lion’s tooth, blowball, or puffball once the flowers turn into round, white seed heads.

Every part of the dandelion is edible, but you will want to avoid harvesting from places treated with pesticides or roadside areas with heavy car traffic. Besides being a food source, dandelions have been used traditionally for simple herbal remedies and natural dye projects.

Young dandelion leaves have a slightly bitter, peppery flavor that works well in salads or sautés, and the flowers can be fried into fritters or brewed into tea. Some people even roast the roots to make a coffee substitute with a rich, earthy taste.

One thing to watch out for is cat’s ear, a common lookalike with hairy leaves and branching flower stems instead of a single, hollow one. To make sure you have a true dandelion, check for a smooth, hairless stem that oozes a milky sap when broken.

Red Raspberry (Rubus idaeus)

The red raspberry, also called wild raspberry or bramble raspberry, grows on prickly, arching canes with compound leaves and clusters of red drupelets. You’ll usually find them forming loose thickets, with berries that pull away cleanly from the core when ripe.

The fruit is sweet-tart and juicy with a soft, seedy texture, often used in jams, jellies, or baked into pies. Leaves and stems aren’t edible and shouldn’t be consumed.

While it looks a lot like wineberry or thimbleberry, red raspberry’s hollow core and matte, soft drupelets help separate it from those. Wineberries, in particular, have a shiny, sticky coating and red bristles on their stems.

Unwashed berries can sometimes host small insects or eggs, so rinse them thoroughly before eating or preserving. The fruit can also be frozen or dried for later use, though fresh is when it’s most flavorful.

Cattail (Typha latifolia)

Cattails, often called bulrushes or corn dog grass, are easy to spot with their tall green stalks and brown, sausage-shaped flower heads. They grow thickly along the edges of ponds, lakes, and marshes, forming dense stands that are hard to miss.

Almost every part of the cattail is edible, including the young shoots, flower heads, and starchy rhizomes. You can eat the tender shoots raw, boil the flower heads like corn on the cob, or grind the rhizomes into flour for baking.

Besides food, cattails have long been used for making mats, baskets, and even insulation by weaving the dried leaves and using the fluffy seeds. Their combination of usefulness and abundance has made them an important survival plant for many cultures.

One thing you need to watch for is young cattail shoots being confused with similar-looking plants like iris, which are toxic. A real cattail shoot will have a mild cucumber-like smell when you snap it open, while iris plants smell bitter or unpleasant.

Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus)

Jerusalem artichoke grows tall with sunflower-like blooms and has knobby underground tubers. The tubers are tan or reddish and look a bit like ginger root, though they belong to the sunflower family.

The part you’re after is the tuber, which has a nutty, slightly sweet flavor and a crisp texture when raw. You can roast, sauté, boil, or mash them like potatoes, and they hold their shape well in soups and stir-fries.

Some people experience gas or bloating after eating sunchokes due to the inulin they contain, so it’s a good idea to try a small amount first. Cooking them thoroughly can help reduce the chances of digestive discomfort.

Sunchokes don’t have many dangerous lookalikes, but it’s important not to confuse the plant with other sunflower relatives that don’t produce tubers. The above-ground part resembles a small sunflower, but it’s the knotted, underground tubers that are worth digging up.

Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

Known for its thick stems, broad leaves, and clusters of pinkish-purple flowers, common milkweed is sometimes called silkweed or butterfly flower. When you snap a stem or leaf, it releases a milky sap that helps you tell it apart from other plants that can be harmful.

If you want to try it in the kitchen, focus on gathering the young shoots, the tightly closed flower buds, and the small, immature pods. These parts have a mild, slightly sweet flavor when cooked, and their soft texture makes them a good addition to soups, sautés, and fritters.

Getting it ready to eat takes a little care, since boiling the plant parts in several changes of water helps remove bitterness and unwanted compounds. Some people also like to steam the buds or fry the pods lightly to bring out their best taste.

Although monarch caterpillars rely on this plant for survival, it has a long history of being used by people as well. Watch out for lookalikes like dogbane, though, since they share the same milky sap but are dangerously toxic if eaten.

Lowbush Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

Lowbush blueberries grow on shrub with smooth-edged, oval leaves and clusters of small white or pinkish bell-shaped flowers. The berries start green and ripen to a deep blue with a dusty-looking skin that easily rubs off.

A few lookalikes can confuse foragers, like the berries of Virginia creeper or pokeweed, but the differences are clear when you know what to check. True blueberries grow on woody shrubs and have a five-pointed crown on the bottom of each berry, while dangerous lookalikes often grow on vines or have no crown at all.

Blueberries have a sweet, sometimes tangy flavor and a juicy texture that makes them great for fresh eating. You can also bake them into pies, simmer them into jams, or dry them for snacks.

Only the ripe berries are eaten, while the leaves and stems are usually left alone.

Interestingly, blueberries is that they contain natural pigments that can turn recipes and even your fingers a deep purple when handled.

Plant

New England aster features vibrant purple daisy-like flowers, golden centers, and tall stalks covered in short white hairs. The plant grows thick and full, often forming dense stands.

Smooth aster lacks the coarse hair and has more delicate, widely spaced blooms, making it less ideal for eating. White heath aster may grow in similar places but has much smaller flowers and a sharper, unpleasant taste.

Both the leaves and flower petals are edible, though the stems should be avoided due to their woody texture. Use the petals raw or steeped in hot water to extract their subtle color and flavor.

Leaves are best cooked or steeped, as they can feel too stiff and bitter when raw. They work well as a secondary green in soups or as a light addition to stir-fry when softened.

Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica)

Stinging nettle is also known as burn weed or devil leaf, and it definitely earns those names. The tiny hairs on its leaves and stems can leave a painful, tingling rash if you brush against it raw, so always wear gloves when handling it.

Once it’s cooked or dried, those stingers lose their punch, and the leaves turn mild and slightly earthy in flavor. The texture softens too, making it a solid substitute for spinach in soups, pastas, or even as a simple sauté.

The young leaves and tender tops are what you want to collect. Avoid the tough lower stems and older leaves, which can be gritty or unpleasant to chew.

Some people confuse stinging nettle with purple deadnettle or henbit, but those don’t sting and have more rounded, fuzzy leaves. If the plant doesn’t make your skin react, it’s not stinging nettle.

Broadleaf Dock (Rumex obtusifolius)

Broadleaf dock gives you broad, slightly puckered leaves with a waxy surface and tall seed stalks that rise late in its growth cycle. The edible part is the young leaf, though only when it’s tender and not yet bitter.

The flavor is sour and tangy, and the texture stays firm even after a quick boil. Some people chop it into stews or stuff it into dumplings and pastries after cooking.

Its closest lookalike, curly dock, has narrower, more curled leaf edges and a rougher surface. If you’re unsure, tear a leaf—broadleaf dock is smoother and less stringy along the stem.

Avoid the roots and seeds—they’re not edible and don’t have culinary use. Stick to cooking the leaves lightly and use them in savory dishes where you’d use chard or mustard greens.

Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

Wild strawberry, sometimes called Virginia strawberry or mountain strawberry, grows low to the ground with three-part leaves that have jagged edges. The small white flowers with yellow centers eventually give way to tiny, bright red fruits nestled close to the soil.

The fruits are sweet with a burst of tartness, and their texture is much softer than the large cultivated strawberries you find in stores. You can eat them raw, mix them into jams, or bake them into pies for a rich, fruity flavor.

Wild strawberry can sometimes be confused with mock strawberry, which has similar leaves but produces dry, flavorless fruits and yellow flowers instead of white. Always check the flower color and taste a small piece before collecting more.

Only the berries and the tender young leaves of wild strawberry are edible, with the leaves often brewed into teas. Be careful not to overharvest because these plants grow slowly and support plenty of small wildlife.

Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album)

Lamb’s quarters, also called wild spinach and pigweed, has soft green leaves that often look dusted with a white, powdery coating. The leaves are shaped a little like goose feet, with slightly jagged edges and a smooth underside that feels almost velvety when you touch it.

A few plants can be confused with lamb’s quarters, like some types of nightshade, but true lamb’s quarters never have berries and its leaves are usually coated in that distinctive white bloom. Always check that the stems are grooved and not round and smooth like the poisonous lookalikes.

When you taste lamb’s quarters, you will notice it has a mild, slightly nutty flavor that gets richer when cooked. The young leaves, tender stems, and even the seeds are all edible, but you should avoid eating the older stems because they become tough and stringy.

People often sauté lamb’s quarters like spinach, blend it into smoothies, or dry the leaves for later use in soups and stews. It is also rich in oxalates, so you will want to cook it before eating large amounts to avoid any problems.

Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica)

With its reddish-green stems and large spade-shaped leaves, Japanese knotweed—also called monkey weed—can be a surprisingly tasty wild ingredient. It has a strong, lemony flavor that mellows with cooking and pairs well with fruit.

People sometimes confuse it with giant ragweed or pokeweed, but knotweed stems are smooth, hollow, and ridged at the nodes, unlike the solid or grooved stems of those toxic lookalikes. Always focus on the young, flexible shoots, discarding any that feel stiff or woody.

Simmered into jams, blended into dressings, or used in baked goods, this plant transforms into something tart and refreshing. Peeled stalks can also be quick-pickled or sautéed.

You don’t want to eat the leaves or roots, and it’s smart to avoid areas sprayed with herbicides. Despite being considered a nuisance plant, it’s highly versatile in the kitchen.

American Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon)

American cranberries grow on trailing vines and produce firm, round berries that turn deep red when mature. The flesh is tart, slightly woody, and not sweet unless cooked or sweetened.

The closest visual mix-up tends to be with swamp-loving bog rosemary, which looks similar but is toxic and has narrow leaves with rolled edges. Cranberry leaves are broader, leathery, and evergreen, while bog rosemary gives off a medicinal smell when bruised.

People usually boil cranberries into sauces or bake them into bread and cakes after adding sugar or orange zest to cut the bitterness. Drying them with sweetener turns them into chewy snacks with a tangy punch.

Only the fruit is eaten; the rest of the plant isn’t dangerous but has no culinary value. The berry contains a high amount of natural pectin, making it ideal for jellies and thick preserves without added thickeners.

Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

Garlic mustard, sometimes called poor man’s mustard or hedge garlic, has heart-shaped leaves with scalloped edges and small white four-petaled flowers. When you crush the leaves between your fingers, they release a strong garlic-like smell that makes it stand out from similar-looking plants.

The flavor of garlic mustard is sharp and garlicky at first bite, with a peppery bitterness that lingers. Its young leaves are often blended into pestos, stirred into soups, or tossed into salads to add a punch of flavor.

You can also use the roots, which have a taste similar to horseradish when fresh. The seed pods are sometimes collected and used as a spicy seasoning after being dried and crushed.

If you decide to gather some, make sure not to confuse it with plants like ground ivy or purple deadnettle, which do not have that garlic aroma. Stick to harvesting the leaves, flowers, seeds, and roots, and avoid anything with a fuzzy texture or a very different smell.

Pine (Pinus spp.)

Pine trees offer several edible parts, including the fresh needles, which are used to make tea with a piney, slightly sour flavor. Their bundles of long, slender needles make them easy to separate from toxic lookalikes like yew, which has flat, single needles.

The seeds—pine nuts—are tucked away between the scales of mature cones and are highly nutritious. They’re often toasted to bring out their rich, oily flavor and are commonly added to trail mixes and pasta dishes.

You can scrape the soft white layer of inner bark and dry it into flour, though it’s mostly a fallback food. This layer is chewy when raw and works best when baked or roasted.

Not all pines are safe to eat, and some species contain compounds that can upset your stomach. When in doubt, Eastern White Pine is one of the most widely accepted edible types.

Wild Leek / Ramp (Allium tricoccum)

Known as wild leek, ramp, or ramson, this flavorful plant is famous for its broad green leaves and slender white stems. It grows low to the ground and gives off a strong onion-like scent when bruised, which can help you tell it apart from toxic lookalikes like lily of the valley.

If you give it a taste, you will notice a bold mix of onion and garlic flavors, with a tender texture that softens even more when cooked. People often sauté the leaves and stems, pickle the bulbs, or blend them into pestos and soups.

The entire plant can be used for cooking, but the leaves and bulbs are the most prized parts. It is important not to confuse it with similar-looking plants that do not have the signature onion smell when crushed.

Wild leek populations have declined in some areas because of overharvesting, so it is a good idea to only take a few from any given patch. When harvested thoughtfully, these vibrant greens can add a punch of flavor to just about anything you make.

Hop Clover (Trifolium campestre)

Hop clover has soft, green trifoliate leaves and rounded yellow flower heads that turn brown and papery as they dry. The flowers and leaves are edible, but skip the stems and roots, which are stringy and unpleasant.

Its taste is mild and grassy, with a barely-sweet hint that works well in herbal teas or chopped into cold grain salads. Some people also add the raw leaves to sandwiches or fold them into soft cheese spreads.

White clover and hop clover look similar, but white clover produces whitish flower balls and tends to grow flatter to the ground. The yellow coloring of hop clover is your clearest sign it’s not white or red clover.

Don’t overdo it—eating large amounts may cause bloating or mild digestive upset in some people. Stick to small quantities, especially if you’re eating it raw.

Elderberry (Sambucus nigra subsp. canadensis)

Elderberry is often called American elder, common elder, or sweet elder. It grows as a large, shrubby plant with clusters of tiny white flowers that eventually turn into deep purple to black berries.

You can recognize elderberry by its compound leaves with five to eleven serrated leaflets and its flat-topped flower clusters. One important thing to watch out for is its toxic lookalikes, like pokeweed, which has very different smooth-edged leaves and reddish stems.

The ripe berries have a tart, almost earthy flavor and a soft texture when cooked. People usually cook elderberries into syrups, jams, pies, or wine because eating raw berries can cause nausea.

Only the ripe, cooked berries and flowers are edible, while the leaves, stems, and unripe berries are toxic. Always take care to strip the berries cleanly from their stems before using them, as even small bits of stem can cause problems.

Beech (Fagus grandifolia)

From the American beech tree—also nicknamed white beech—you can collect small, three-sided nuts that are tightly enclosed in a spiny outer husk. They’re best roasted or pan-dried to bring out their buttery texture and mellow flavor.

The husks naturally open on their own once the nuts are ready, and you’ll often find two shiny brown seeds inside. Don’t eat them raw in large amounts, since they contain small amounts of oxalic acid that cooking neutralizes.

Beech trees are easy to confuse with chestnut trees at a glance, but chestnut leaves have longer tapering tips and the husks are far more heavily armored with spines. Avoid picking from horse chestnut, which has poisonous seeds that look similar.

Once prepared, the nuts can be added to soups or ground into a coarse flour for baked goods. Nothing else from the tree is eaten—only the seeds inside the husks are used.

Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

There are plenty of wild edibles to choose from, but some toxic native plants closely resemble them. Mistaking the wrong one can lead to severe illness or even death, so it’s important to know exactly what you’re picking.

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild carrot (Daucus carota)

Poison hemlock is a tall plant with lacy leaves and umbrella-like clusters of tiny white flowers. It has smooth, hollow stems with purple blotches and grows in sunny places like roadsides, meadows, and stream banks.

Unlike wild carrot, which has hairy stems and a dark central floret, poison hemlock has a musty odor and no flower center spot. It’s extremely toxic; just a small amount can be fatal, and even touching the sap can irritate the skin.

Water Hemlock (Cicuta spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) or wild celery (Apium spp.)

Water hemlock is a tall, branching plant with umbrella-shaped clusters of small white flowers. It grows in wet places like stream banks, marshes, and ditches, with stems that often show purple streaks or spots.

It can be confused with wild parsnip or wild celery, but its thick, hollow roots have internal chambers and release a yellow, foul-smelling sap when cut. Water hemlock is the most toxic plant in North America, and just a small amount can cause seizures, respiratory failure, and death.

False Hellebore (Veratrum viride)

Often mistaken for: Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

False hellebore is a tall plant with broad, pleated green leaves that grow in a spiral from the base, often appearing early in spring. It grows in moist woods, meadows, and along streams.

It’s commonly mistaken for ramps, but ramps have a strong onion or garlic smell, while false hellebore is odorless and later grows a tall flower stalk. The plant is highly toxic, and eating any part can cause nausea, a slowed heart rate, and even death due to its alkaloids that affect the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Death Camas (Zigadenus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild onion or wild garlic (Allium spp.)

Death camas is a slender, grass-like plant that grows from underground bulbs and is found in open woods, meadows, and grassy hillsides. It has small, cream-colored flowers in loose clusters atop a tall stalk.

It’s often confused with wild onion or wild garlic due to their similar narrow leaves and habitats, but only Allium plants have a strong onion or garlic scent, while death camas has none. The plant is extremely poisonous, especially the bulbs, and even a small amount can cause nausea, vomiting, a slowed heartbeat, and potentially fatal respiratory failure.

Buckthorn Berries (Rhamnus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Elderberries (Sambucus spp.)

Buckthorn is a shrub or small tree often found along woodland edges, roadsides, and disturbed areas. It produces small, round berries that ripen to dark purple or black and usually grow in loose clusters.

These berries are sometimes mistaken for elderberries and other wild fruits, which also grow in dark clusters, but elderberries form flat-topped clusters on reddish stems while buckthorn berries are more scattered. Buckthorn berries are unsafe to eat as they contain compounds that can cause cramping, vomiting, and diarrhea, and large amounts may lead to dehydration and serious digestive problems.

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Mayapple is a low-growing plant found in shady forests and woodland clearings. It has large, umbrella-like leaves and produces a single pale fruit hidden beneath the foliage.

The unripe fruit resembles a small green grape, causing confusion with wild grapes, which grow in woody clusters on vines. All parts of the mayapple are toxic except the fully ripe, yellow fruit, which is only safe in small amounts. Eating unripe fruit or other parts can lead to nausea, vomiting, and severe dehydration.

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Virginia creeper is a fast-growing vine found on fences, trees, and forest edges. It has five leaflets per stem and produces small, bluish-purple berries from late summer to fall.

It’s often confused with wild grapes since both are climbing vines with similar berries, but grapevines have large, lobed single leaves and tighter fruit clusters. Virginia creeper’s berries are toxic to humans and contain oxalate crystals that can cause nausea, vomiting, and throat irritation.

Castor Bean (Ricinus communis)

Often mistaken for: Wild rhubarb (Rumex spp. or Rheum spp.)

Castor bean is a bold plant with large, lobed leaves and tall red or green stalks, often found in gardens, along roadsides, and in disturbed areas in warmer regions in the US. Its red-tinged stems and overall size can resemble wild rhubarb to the untrained eye.

Unlike rhubarb, castor bean plants produce spiny seed pods containing glossy, mottled seeds that are extremely toxic. These seeds contain ricin, a deadly compound even in small amounts. While all parts of the plant are toxic, the seeds are especially dangerous and should never be handled or ingested.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

How to Get the Best Results Foraging

Safety should always come first when it comes to foraging. Whether you’re in a rural forest or a suburban greenbelt, knowing how to harvest wild foods properly is a key part of staying safe and respectful in the field.

Always Confirm Plant ID Before You Harvest Anything

Knowing exactly what you’re picking is the most important part of safe foraging. Some edible plants have nearly identical toxic lookalikes, and a wrong guess can make you seriously sick.

Use more than one reliable source to confirm your ID, like field guides, apps, and trusted websites. Pay close attention to small details. Things like leaf shape, stem texture, and how the flowers or fruits are arranged all matter.

Not All Edible Plants Are Safe to Eat Whole

Just because a plant is edible doesn’t mean every part of it is safe. Some plants have leaves, stems, or seeds that can be toxic if eaten raw or prepared the wrong way.

For example, pokeweed is only safe when young and properly cooked, while elderberries need to be heated before eating. Rhubarb stems are fine, but the leaves are poisonous. Always look up which parts are edible and how they should be handled.

Avoid Foraging in Polluted or Contaminated Areas

Where you forage matters just as much as what you pick. Plants growing near roads, buildings, or farmland might be coated in chemicals or growing in polluted soil.

Even safe plants can take in harmful substances from the air, water, or ground. Stick to clean, natural areas like forests, local parks that allow foraging, or your own yard when possible.

Don’t Harvest More Than What You Need

When you forage, take only what you plan to use. Overharvesting can hurt local plant populations and reduce future growth in that area.

Leaving plenty behind helps plants reproduce and supports wildlife that depends on them. It also ensures other foragers have a chance to enjoy the same resources.

Protect Yourself and Your Finds with Proper Foraging Gear

Having the right tools makes foraging easier and safer. Gloves protect your hands from irritants like stinging nettle, and a good knife or scissors lets you harvest cleanly without damaging the plant.

Use a basket or breathable bag to carry what you collect. Plastic bags hold too much moisture and can cause your greens to spoil before you get home.

This forager’s toolkit covers the essentials for any level of experience.

Watch for Allergic Reactions When Trying New Wild Foods

Even if a wild plant is safe to eat, your body might react to it in unexpected ways. It’s best to try a small amount first and wait to see how you feel.

Be extra careful with kids or anyone who has allergies. A plant that’s harmless for one person could cause a reaction in someone else.

Check Local Rules Before Foraging on Any Land

Before you start foraging, make sure you know the rules for the area you’re in. What’s allowed in one spot might be completely off-limits just a few miles away.

Some public lands permit limited foraging, while others, like national parks, usually don’t allow it at all. If you’re on private property, always get permission first.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

Where to Find Forageables in the State

There is a range of foraging spots where edible plants grow naturally and often in abundance:

| Plant | Locations |

| Elderberry (Sambucus nigra subsp. canadensis) | – Arcadia Management Area – Lincoln Woods State Park – Ninigret National Wildlife Refuge |

| Chicory (Cichorium intybus) | – Fort Adams State Park – Colt State Park – Blackstone River State Park |

| Common Plantain (Plantago major) | – Roger Williams Park – Haines Memorial State Park – Beavertail State Park |

| Wild Rose (Rosa spp.) | – Trustom Pond National Wildlife Refuge – Sachuest Point National Wildlife Refuge – Snake Den State Park |

| Sheep Sorrel (Rumex acetosella) | – East Beach Management Area – Burlingame State Park – Beavertail State Park |

| American Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) | – Carolina Management Area – Great Swamp Management Area – Tillinghast Pond Management Area |

| Hazelnut (Corylus americana) | – George Washington Management Area – Big River Management Area – Arcadia Management Area |

| Red Raspberry (Rubus idaeus) | – Browning Mill Pond Area – Pulaski Park – Burlingame State Park |

| Pine (Pinus spp.) | – Goddard Memorial State Park – Lincoln Woods State Park – Arcadia Management Area |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | – Blackstone River State Park – Brenton Point State Park – Fort Wetherill State Park |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | – Fort Adams State Park – Haines Memorial State Park – Roger Williams Park |

| Spearmint (Mentha spicata) | – Ninigret National Wildlife Refuge – Great Swamp Management Area – Tillinghast Pond Management Area |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.) | – Arcadia Management Area – George Washington Management Area – Browning Mill Pond Area |

| Bee Balm (Monarda didyma) | – Pulaski Park – Big River Management Area – Snake Den State Park |

| New England Aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae) | – Fort Wetherill State Park – Burlingame State Park – Trustom Pond National Wildlife Refuge |

| Peppermint (Mentha × piperita) | – Great Swamp Management Area – Ninigret National Wildlife Refuge – Tillinghast Pond Management Area |

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) | – George Washington Management Area – Arcadia Management Area – Fort Adams State Park |

| Lowbush Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) | – Carolina Management Area – Big River Management Area – Pulaski Park |

| Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) | – Roger Williams Park – Snake Den State Park – Blackstone River State Park |

| Common Burdock (Arctium minus) | – Beavertail State Park – Brenton Point State Park – Colt State Park |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | – Trustom Pond National Wildlife Refuge – Great Swamp Management Area – Fort Barton Woods |

| Wild Leek / Ramp (Allium tricoccum) | – Arcadia Management Area – George Washington Memorial Camping Area – Durfee Hill Management Area |

| Common Ground Cherry (Physalis longifolia) | – Browning Mill Pond Area – Haines Memorial State Park – Black Farm State Management Area |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta) | – Tillinghast Pond Management Area – Ninigret National Wildlife Refuge – Lincoln Woods State Park |

| Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) | – Pawtuxet River Trail – Blackstone River Bikeway – Wickaboxet Management Area |

| Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina) | – Sachuest Point National Wildlife Refuge – Snake Den State Park – Fort Wetherill State Park |

| Beech (Fagus grandifolia) | – Carolina Management Area – Nicholas Farm Management Area – Beach Pond Forest |

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | – Beavertail State Park – Camp Cronin Fishing Area – East Beach Management Area |

| Common Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis) | – Fort Adams State Park – Napatree Point Conservation Area – Burlingame State Park |

| Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | – Roger Williams Park – Neutaconkanut Hill Conservancy – Cliff Walk Trail (woodland segments) |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | – Colt State Park – Fort Getty Park – Brenton Point State Park |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | – John H. Chafee Nature Preserve – Little Compton Wildlife Refuge – Hundred Acre Cove |

| Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | – Dexter Training Grounds – Swan Point Cemetery (public-access side trails) – Warwick City Park |

| Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) | – Norman Bird Sanctuary – Rome Point Trail – Camp Hoffman Conservation Area |

| Broadleaf Dock (Rumex obtusifolius) | – Salter Grove Memorial Park – Meshanticut State Park – Fields at Fort Greene Army Reserve |

| Hop Clover (Trifolium campestre) | – Fort Ninigret Grounds – Goddard Memorial State Park – India Point Park |

| Hickory (Carya spp.) | – Big River Management Area – Moosup Valley State Park Trail – Durfee Hill Management Area |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | – Great Swamp Management Area – Maxwell Mays Wildlife Refuge – King Benson Preserve |

Peak Foraging Seasons

Different edible plants grow at different times of year, depending on the season and weather. Timing your search makes all the difference.

Spring

Spring brings a fresh wave of wild edible plants as the ground thaws and new growth begins:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) | March – May | Cool, overcast, or damp days after rain |

| Common Burdock (Arctium minus) | March – May | Damp soil, partly cloudy skies |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | March – May | Sunny or lightly overcast with moist ground |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | March – May | Mild days with damp understory soil |

| Wild Leek / Ramp (Allium tricoccum) | April – May | Cool, moist forest soil after rainfall |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.) | April – May | Clear, cool days before fruit matures |

| Common Plantain (Plantago major) | April – May | Moist soil and light rain, early morning for best harvest |

| Spearmint (Mentha spicata) | April – May | Cool, shaded areas after light rain |

| Peppermint (Mentha × piperita) | April – May | Overcast days or after a rainstorm |

| Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | April – May | Overcast days or just after rain |

| Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) | April – May | Warm, wet spring days just after sprouting |

| Broadleaf Dock (Rumex obtusifolius) | April – May | Overcast weather or post-rain conditions |

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) | April – June | Mild, sunny days with moist soil |

| Sheep Sorrel (Rumex acetosella) | April – June | Light rain or early morning dew in sunny fields |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | April – June | Overcast or partly cloudy with soft ground |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta) | April – June | Light rain or morning dew in partial shade |

| Hop Clover (Trifolium campestre) | April – June | Sunny mornings with well-drained soil |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | May | Warm spring days after rain |

Summer

Summer is a peak season for foraging, with fruits, flowers, and greens growing in full force:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | June – July | Sunny mornings after rainfall |

| Wild Rose (Rosa spp.) | June – July | Warm, breezy days when petals are dry |

| Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) | June – July | After early summer rain, before stems get tough |

| Red Raspberry (Rubus idaeus) | June – August | Warm, dry mornings with full sun |

| Chicory (Cichorium intybus) | June – August | Dry, sunny weather with firm soil |

| Bee Balm (Monarda didyma) | June – August | Warm, sunny afternoons with low wind |

| Common Plantain (Plantago major) | June – August | Dry weather or dewy mornings |

| Spearmint (Mentha spicata) | June – August | Shaded areas, early morning or post-rain |

| Peppermint (Mentha × piperita) | June – August | Cool, moist areas with morning sun |

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | June – August | Warm, dry weather with full sun |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | June – August | Dry conditions or dewy mornings |

| Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) | June – August | Warm, dry afternoons with good sunlight |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta) | June – August | Shaded or lightly moist soils after summer showers |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | June – August | Hot, sunny days in marshy areas |

| Elderberry (Sambucus nigra subsp. canadensis) | July – August | Sunny days after several days of rain for plump berries |

| Lowbush Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) | July – August | Hot, sunny days after rain |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | July – August | Humid, shady woodlands with moist soil |

| Common Ground Cherry (Physalis longifolia) | July – September | Hot, dry days with full sun |

| Common Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis) | July – September | Sunny, dry conditions, best in evening |

Fall

As temperatures drop, many edible plants shift underground or produce their last harvests:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina) | August – September | After dry spells, before rain dilutes flavor |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | September | Warm afternoons before seeds drop |

| Spearmint (Mentha spicata) | September | Lightly shaded areas, especially after rainfall |

| Peppermint (Mentha × piperita) | September | Damp soil, overcast mornings |

| Hop Clover (Trifolium campestre) | September | Cool, sunny days after late summer rain |

| American Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) | September – October | Cool, crisp mornings after light frost |

| Hazelnut (Corylus americana) | September – October | Dry weather, just before or after nuts fall |

| New England Aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae) | September – October | Mild days with high sun and dry air |

| Common Burdock (Arctium minus) | September – October | Moist soil, overcast days for root harvest |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | September – October | Cool, post-rain conditions |

| Common Plantain (Plantago major) | September – October | Moist mornings or after gentle rainfall |

| Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | September – October | Dry days after nut drop, before heavy frost |

| Hickory (Carya spp.) | September – October | Crisp, dry mornings during nut fall |

| Common Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis) | September – October | Cool, dry evenings for seed pods and roots |

| Broadleaf Dock (Rumex obtusifolius) | September – October | Damp soil on cloudy days for root harvest |

| Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | September – October | After rainfall, during second-year rosettes |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta) | September – October | Soft, damp soil with filtered sunlight |

| Pine (Pinus spp.) | September – November | Dry conditions for needle collection, after wind events |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | September – November | After first frost, cool mornings for digging |

Winter

Winter foraging is limited but still possible, with hardy plants and preserved growth holding on through the cold:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Peppermint (Mentha × piperita) | December – January | Root foraging in damp, unfrozen streambanks |

| Pine (Pinus spp.) | December – February | Cold, dry days after windstorms for fresh needle collection |

| Common Burdock (Arctium minus) | December – February | Dig roots during unfrozen soil periods on cloudy days |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | December – February | Root harvest during soft ground thaws |

| Sheep Sorrel (Rumex acetosella) | December – February | Sunny or lightly frosted ground with exposed patches |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | December – February | Mild winter days with unfrozen ground |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | December – February | Frozen marshes for root and shoot access |

| Beech (Fagus grandifolia) | December – February | After frost drop, dry days for collecting nuts |

| Broadleaf Dock (Rumex obtusifolius) | December – February | Root collection during soil thaws |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | December – February | Branch and twig harvesting during dormancy |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | December – February | Root digging during mild winter thaws |

| Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) | January – February | Only roots are accessible; dig during thawed soil periods |

| Common Plantain (Plantago major) | January – February | Root and seed head collection during mild winter days |

| Hickory (Carya spp.) | January – February | Cold, dry days to collect fallen nuts |

| Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | January – February | Dry, leafless periods to locate and gather fallen nuts |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.