Across California’s coastlines, valleys, and foothills, edible plants thrive in surprising abundance. You can find dozens of plants hiding in plain sight across meadows, mountains, and coastal bluffs.

Many plants that grow wild in California have long histories as food and medicine. For example, cattails near marshy areas and elderberries growing in sunny clearings are among the many wild ingredients you can gather. The trick is knowing how to find them without mistaking them for similar plants.

Whether you explore dense forests or dry hillsides, you are likely walking past a buffet of edible plants without realizing it. Knowing what to look for can turn a simple walk into a trip filled with incredible edible discoveries.

What We Cover In This Article:

- The Edible Plants Found in the State

- Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

- How to Get the Best Results Foraging

- Where to Find Forageables in the State

- Peak Foraging Seasons

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

The Edible Plants Found in the State

Wild plants found across the state can add fresh, seasonal ingredients to your meals:

Miner’s Lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata)

Miner’s lettuce, also known as Indian lettuce and winter purslane, has round, cup-shaped leaves that almost look like they are threaded through the stem. Tiny white flowers often bloom right in the center of the leaf, giving it a distinctive, easy-to-spot look if you are paying attention.

The leaves and stems are edible and have a crisp, tender texture with a mild, slightly sweet flavor. Some people describe the taste as a little like spinach but even fresher and lighter when eaten raw.

You can toss miner’s lettuce straight into salads, blend it into smoothies, or lightly sauté it for a simple side dish. It also holds up well when added to sandwiches or wrapped in tortillas if you want a bit of fresh crunch.

While it is generally safe to eat, it is important to avoid confusing miner’s lettuce with toxic lookalikes like young spurge plants, which have a milky sap if snapped. Always double-check that the stems are smooth and the flowers are small and white before harvesting anything to eat.

Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album)

Lamb’s quarters, also called wild spinach and pigweed, has soft green leaves that often look dusted with a white, powdery coating. The leaves are shaped a little like goose feet, with slightly jagged edges and a smooth underside that feels almost velvety when you touch it.

A few plants can be confused with lamb’s quarters, like some types of nightshade, but true lamb’s quarters never have berries and its leaves are usually coated in that distinctive white bloom. Always check that the stems are grooved and not round and smooth like the poisonous lookalikes.

When you taste lamb’s quarters, you will notice it has a mild, slightly nutty flavor that gets richer when cooked. The young leaves, tender stems, and even the seeds are all edible, but you should avoid eating the older stems because they become tough and stringy.

People often sauté lamb’s quarters like spinach, blend it into smoothies, or dry the leaves for later use in soups and stews. It is also rich in oxalates, so you will want to cook it before eating large amounts to avoid any problems.

Chickweed (Stellaria media)

Chickweed, sometimes called satin flower or starweed, is a small, low-growing plant with delicate white star-shaped flowers and bright green leaves. The leaves are oval, pointed at the tip, and often grow in pairs along a slender, somewhat weak-looking stem.

When gathering chickweed, watch out for lookalikes like scarlet pimpernel, which has similar leaves but orange flowers instead of white. A key detail to check is the fine line of hairs that runs along one side of chickweed’s stem, a feature the dangerous lookalikes do not have.

The young leaves, tender stems, and flowers of chickweed are all edible, offering a mild, slightly grassy flavor with a crisp texture. You can toss it fresh into salads, blend it into pestos, or lightly wilt it into soups and stir-fries for a fresh green boost.

Aside from being a food plant, chickweed has been used traditionally in poultices and salves to help soothe skin irritations. Always make sure the plant is positively identified before eating, since mistaking it for a toxic lookalike could cause serious issues.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

Bright yellow flowers and jagged, deeply toothed leaves make dandelions easy to spot in open fields, lawns, and roadsides. You might also hear them called lion’s tooth, blowball, or puffball once the flowers turn into round, white seed heads.

Every part of the dandelion is edible, but you will want to avoid harvesting from places treated with pesticides or roadside areas with heavy car traffic. Besides being a food source, dandelions have been used traditionally for simple herbal remedies and natural dye projects.

Young dandelion leaves have a slightly bitter, peppery flavor that works well in salads or sautés, and the flowers can be fried into fritters or brewed into tea. Some people even roast the roots to make a coffee substitute with a rich, earthy taste.

One thing to watch out for is cat’s ear, a common lookalike with hairy leaves and branching flower stems instead of a single, hollow one. To make sure you have a true dandelion, check for a smooth, hairless stem that oozes a milky sap when broken.

Curly Dock (Rumex crispus)

Curly dock, sometimes called yellow dock, is easy to spot once you know what to look for. It has long, wavy-edged leaves that form a rosette at the base, with tall stalks that eventually turn rusty brown as seeds mature.

The young leaves are edible and often cooked to mellow out their sharp, lemony taste, which can be too strong when eaten raw. You can also dry and powder the seeds to use as a flour supplement, although they are tiny and take some effort to prepare.

Curly dock has some lookalikes, like other types of dock and sorrel, but its heavily crinkled leaf edges and thick taproot help it stand out. Be careful not to confuse it with plants like wild rhubarb, which can have toxic parts if misidentified.

Besides being edible, curly dock has a history of being used in homemade remedies for skin irritation. The roots are not eaten raw because they are tough and contain compounds that can upset your stomach if you are not careful.

Wild Mustard (Brassica rapa, Brassica nigra)

Wild mustard is sometimes called field mustard or black mustard, and it is a surprisingly common wild edible. The plants usually have bright yellow flowers with four petals and slightly fuzzy, lobed leaves that look a little like arugula.

When you are looking for wild mustard, be careful not to confuse it with young poison hemlock, which can have similar leaf shapes but no yellow flowers and a more finely divided, lacy appearance. Wild mustard leaves, stems, flowers, seed pods, and seeds are all edible, but the roots are usually too tough and fibrous to be worth eating.

The flavor of wild mustard can be peppery and sharp when raw, but cooking the leaves or stems softens the taste and brings out a mild, cabbage-like sweetness. People often sauté the greens, pickle the buds, or grind the seeds to make a spicy homemade mustard.

One interesting thing about wild mustard is that it is part of a huge family of plants humans have cultivated for centuries, including broccoli, kale, and turnips. If you harvest wild mustard, make sure you positively identify it, because while it is safe to eat, some toxic plants can look similar when they are young.

Mallow (Malva neglecta, Malva parviflora)

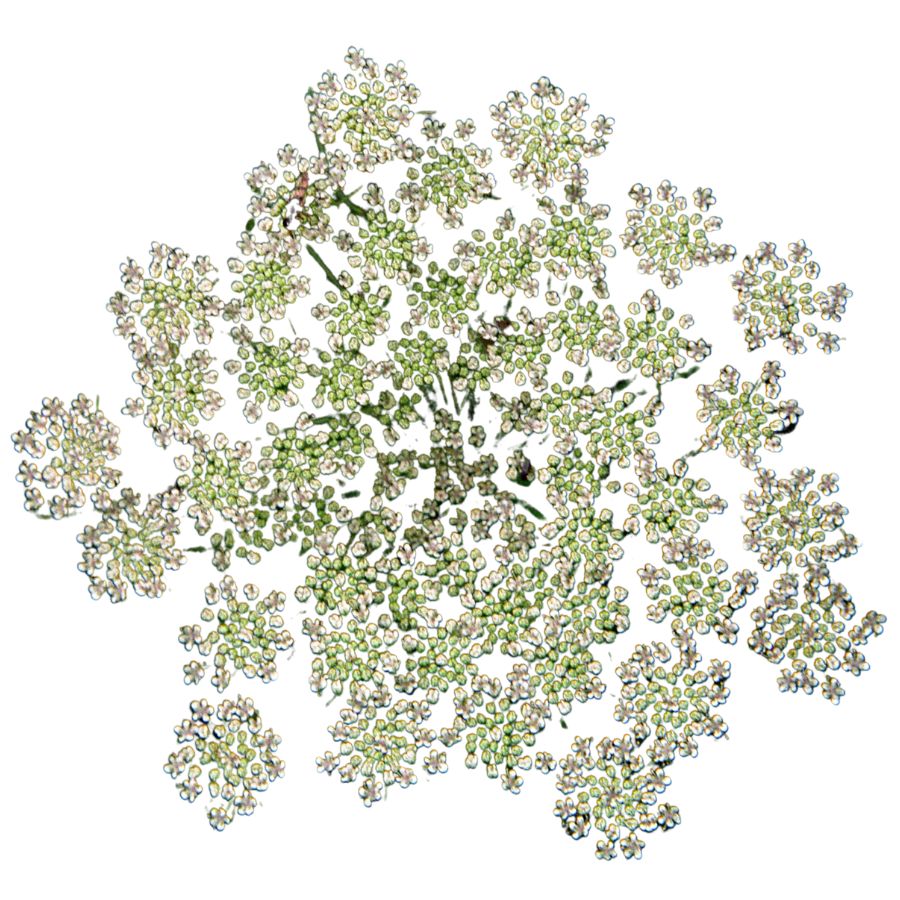

Mallow, often called common mallow or cheeseweed, grows low to the ground and spreads with round, crinkled leaves that look a bit like tiny lily pads. It produces small pale purple or pink flowers with five delicate petals, and the seed pods are shaped like little green wheels.

The leaves, flowers, and immature seed pods of mallow are all edible, offering a mild, slightly sweet flavor and a soft, somewhat mucilaginous texture. Some people add the leaves to salads, toss them into soups for thickening, or quickly sauté them with garlic for a simple side dish.

When gathering mallow, make sure you do not confuse it with young deadly nightshade plants, which can sometimes grow in similar weedy areas but have very different flower and fruit structures. Mallow is safe to eat, but it tends to absorb pollutants from the soil, so be cautious about harvesting from roadsides or contaminated areas.

An interesting thing about mallow is that it was traditionally used for soothing sore throats and irritated skin because of its natural slimy quality. If you are foraging for food and medicine, mallow is a versatile and easy plant to start with once you are confident in your identification.

Sow Thistle (Sonchus oleraceus)

Sow thistle, often called hare’s thistle or milk thistle, is a spiny-leaved plant with bright yellow flowers that resemble small dandelions. The young leaves are tender and green, with a mild flavor that makes them easy to mix into salads or sautés.

The leaves and tender stems are the parts you can eat, and they are often lightly steamed or added raw to dishes for a slight bitter note. Older leaves can get fibrous and less pleasant, so it helps to pick younger plants if you want a smoother texture.

When foraging, make sure you are not confusing sow thistle with prickly lettuce or spiny sow thistle, both of which have sharper spines and a much tougher texture. One good way to tell is by snapping a stem and checking for the milky sap and softer feel that true sow thistle has.

Sow thistle has also been used traditionally for its potential medicinal properties, especially for digestion. Always harvest away from roadsides or treated areas, since the leaves can easily absorb chemicals from the surrounding environment.

Watercress (Nasturtium officinale)

Watercress, also known as yellowcress or garden cress, is an aquatic plant with small, rounded green leaves and hollow stems that often float along the water’s surface. It usually grows in dense mats, and the bright green color is one of the easiest ways to spot it in clear, shallow streams and ponds.

Besides being a popular edible green, watercress has been traditionally used in herbal remedies, especially for boosting digestion and respiratory health.

The leaves and stems are edible, offering a crisp texture and a peppery, slightly spicy taste that can remind you of arugula. People often enjoy it raw in salads, blended into soups, or lightly wilted into stir-fries for a fresh bite.

Stick to eating the leaves and stems, and avoid any parts that look yellowed or slimy, since healthy watercress should always look vibrant and clean.

Watercress has a few lookalikes like lesser celandine or young wild mustard, but true watercress has a distinct sharp flavor and tends to grow only in moving, clean water. Always double-check your identification, because gathering from stagnant or contaminated water sources can expose you to harmful bacteria or parasites.

Wood Sorrel (Oxalis spp.)

Wood sorrel is easy to spot with its clover-like leaves, delicate flowers, and sour flavor. It often goes by names like sourgrass and shamrock, although it is not the same as the traditional Irish shamrock.

Wood sorrel can be mistaken for true clovers, which do not have the same sour taste. Always check the leaf shape and flavor before eating, because wood sorrel leaves are distinctly heart-shaped and more delicate.

The leaves, flowers, and seed pods of wood sorrel are all edible and have a sharp, lemony taste that makes them a refreshing trail snack. You can also toss them into salads or use them as a garnish to brighten up a dish with their tartness.

While wood sorrel is generally safe in small amounts, it does contain oxalic acid, so it is best not to eat large quantities. Some people also like to brew the leaves into a light, tangy tea, adding another way to enjoy this common and flavorful wild plant.

Wild Onion (Allium spp.)

Wild onion, sometimes called meadow garlic or wild garlic, grows with slender green stems and small bulbs tucked just below the surface. The leaves are smooth, narrow, and hollow, giving off a sharp onion scent when crushed between your fingers.

The entire plant is edible, from the crisp bulbs to the tender stems and flowers. Its strong onion flavor can be used fresh, cooked into soups, or even pickled for longer storage.

One important thing to watch for is its lookalike, death camas, which has similar leaves but no onion smell and can be deadly if eaten. Always crush a leaf and check for that familiar onion scent before harvesting any wild onion.

Wild onion adds a punch of flavor to dishes like scrambled eggs, roasted meats, and vegetable sautés. Besides cooking, it has a long history of being used in herbal remedies for colds and minor infections.

Yampah (Perideridia spp.)

Yampah, also known as wild carrot or Indian carrot, grows with feathery, fern-like leaves and small white flowers arranged in delicate clusters. It has slender roots that resemble thin parsnips, often buried just a few inches underground.

The root is the edible part and has a sweet, nutty flavor with a crisp texture when fresh. You can roast it, boil it like a vegetable, or dry it for later use in stews and broths.

It is very important to properly identify yampah, because it looks a lot like toxic plants such as poison hemlock and water hemlock. A true yampah root will smell pleasantly carrot-like when snapped, unlike the unpleasant or musty odor of its deadly lookalikes.

In addition to being a food source, yampah roots were traditionally used by Indigenous peoples for both nourishment and trade. The roots are small, so you often have to gather quite a few to make a meal, but their rich flavor makes the effort worthwhile.

Cattail (Typha latifolia)

Cattails, often called bulrushes or corn dog grass, are easy to spot with their tall green stalks and brown, sausage-shaped flower heads. They grow thickly along the edges of ponds, lakes, and marshes, forming dense stands that are hard to miss.

Almost every part of the cattail is edible, including the young shoots, flower heads, and starchy rhizomes. You can eat the tender shoots raw, boil the flower heads like corn on the cob, or grind the rhizomes into flour for baking.

Besides food, cattails have long been used for making mats, baskets, and even insulation by weaving the dried leaves and using the fluffy seeds. Their combination of usefulness and abundance has made them an important survival plant for many cultures.

One thing you need to watch for is young cattail shoots being confused with similar-looking plants like iris, which are toxic. A real cattail shoot will have a mild cucumber-like smell when you snap it open, while iris plants smell bitter or unpleasant.

Northern California Black Walnut (Juglans hindsii)

Northern California black walnut, also known as Hinds’ black walnut or California black walnut, grows as a medium-sized tree with wide, rounded leaves and deeply furrowed bark. The nuts develop inside thick, green husks that turn dark as they mature, giving off a rich, earthy smell when you crack them open.

The edible part of the plant is the nut inside the hard shell, while the green husk and leaves are not considered edible. The shell is extremely tough, so you will need a strong nutcracker or a hammer to get to the flavorful meat inside.

When you taste Northern California black walnut, you will notice it has a strong, bold flavor that is richer and more astringent than the common English walnut. People often roast the nuts to bring out their sweetness or use them in baked goods like cookies, breads, and cakes.

One thing to watch out for is that the husks stain everything they touch, including your hands and clothes. It would be a good idea to wear gloves when handling them.

Oak (Quercus spp.)

There are different types of oak trees, such as live oaks, white oaks, black oaks, and more. Oak trees are generally are easy to spot by their sturdy trunks and lobed leaves.

Their acorns are the edible part, though you have to properly prepare them to safely enjoy their nutty flavor.

Some types of acorns are very bitter because of high tannin levels, but leaching them in water removes the bitterness. When prepared correctly, acorns can be ground into a sweet, nutty flour that works well for baking or thickening stews.

Besides being a food source, acorns have been used traditionally to make coffee substitutes and animal feed. However, it is important to avoid eating raw acorns because the tannins can cause digestive issues if they are not properly removed.

Be careful not to confuse true oaks with plants like horse chestnuts, which produce similar-looking nuts that are toxic. One way to tell the difference is that true oak acorns have a distinctive, rough-textured cap, while horse chestnuts do not.

Pinyon Pine (Pinus monophylla)

The pinyon pine, sometimes called single-leaf pinyon, is easy to spot because it has just one needle per bundle instead of the usual two or more. The tree stays small and bushy, with a rounded shape and dense clusters of short, bluish-green needles.

The pine nut hidden inside the thick-shelled cones is the only edible part of the tree, and it has a rich, buttery flavor when eaten raw or roasted. The seeds are small compared to commercial pine nuts but have a soft, slightly chewy texture that makes them easy to enjoy by the handful.

You can crack open the shells and eat the seeds fresh, toast them lightly to bring out a deeper flavor, or grind them into sauces or spreads. Only the seeds are edible, so avoid nibbling on the cones, bark, or needles, which are not considered safe to eat.

Make sure not confuse the pinyon pine with other types of pines that either do not produce edible seeds or have seeds too small to bother collecting. Single-leaf pinyon cones are larger and rounder than many other pines, and the tree’s distinctive needle pattern helps make a positive ID.

Currant (Ribes spp.)

Currants are small, shrubby plants that produce clusters of round berries and are often called wild currants or gooseberries, depending on the species. You can recognize them by their lobed leaves, slender stems, and berries that come in shades of red, black, or even golden yellow.

Some currant plants have lookalikes, such as certain types of nightshade, which can be toxic if eaten. To tell them apart, check the leaves and stems closely because real currants have woody stems and leaves that feel soft and slightly rough.

The berries are edible and offer a tart, slightly sweet flavor with a juicy texture that pops when you bite into them. People often use currants to make jams, jellies, syrups, and even baked goods like tarts and cakes.

While currant berries are a treat, the leaves can also be used to flavor teas, although they are not as widely eaten.

It’s important to avoid eating any berries that taste bitter or look unfamiliar, since not all wild berries are safe.

California Poppy (Eschscholzia californica)

The California poppy, also known as golden poppy or cup of gold, is easy to recognize with its bright orange to yellow petals and soft, blue-green leaves. Its silky, bowl-shaped flowers usually close at night or when it is cloudy, adding to their delicate charm.

The leaves and flowers of the California poppy are edible, although they have a slightly bitter, grassy flavor that can be surprising if you are expecting sweetness. Some people like to add the petals to salads for color or steep the leaves in teas, but it is important to use only small amounts.

Aside from culinary uses, California poppy has a history of being used in traditional herbal remedies for its mild calming effects.

Always remember that while the plant is generally safe in small quantities, larger amounts can cause drowsiness and should be avoided if you need to stay alert.

When identifying California poppy, be careful not to confuse it with other orange-flowered plants like Mexican poppy, which has more spiny leaves and a rougher appearance. California poppy’s leaves are smooth and finely divided, almost feathery, which helps set it apart.

Wild Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare)

Wild fennel, sometimes called sweet fennel or common fennel, is easy to recognize once you know what to look for. It grows tall with feathery, bright green leaves and small clusters of yellow flowers, and the whole plant smells strongly of licorice when crushed.

The frilly leaves, tender stems, seeds, and even the pollen of wild fennel are edible, but the mature stalks can become woody and unpleasant to chew. If you find a plant that looks similar but does not have that distinct sweet smell, it could be poison hemlock, which is deadly and should never be touched or eaten.

The leaves have a delicate, slightly sweet flavor that works well in salads, pestos, or sprinkled fresh over fish and pasta dishes. People often toast the seeds to release their warm, anise-like aroma and use them to flavor breads, sausages, or herbal teas.

Some people also harvest the bright yellow fennel pollen, often called “spice gold,” to use as a luxurious seasoning for meats, vegetables, and desserts.

One interesting thing about wild fennel is that it does not form a fat, bulb-like base the way cultivated fennel does, so you will not find a large white bulb underground.

Wild Radish (Raphanus sativus)

Wild radish, sometimes called jointed charlock, can be recognized by its rough, hairy leaves and flowers that range from white to light purple with darker veins. The seed pods are slender and bumpy, almost bead-like, which helps separate it from other wild plants that grow in similar places.

It’s important to know that wild radish can sometimes be confused with wild mustard, which has smoother seed pods and leaves. If you look closely, wild radish leaves are more deeply lobed and feel rougher to the touch, helping you tell them apart with a little practice.

The flowers, seed pods, young leaves, and even the roots of wild radish are edible and have a spicy, peppery taste similar to cultivated radish. You can eat them raw in salads, sauté them with other greens, or pickle the seed pods for a crunchy, flavorful snack.

Even though the plant is edible, make sure that you avoid eating older, woody seed pods or large, tough roots, since they become bitter and unpleasant. Some people also experience mild stomach upset from eating too much wild radish, so it is best to start with small amounts and see how your body reacts.

Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

There are plenty of wild edibles to choose from, but some toxic native plants closely resemble them. Mistaking the wrong one can lead to severe illness or even death, so it’s important to know exactly what you’re picking.

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild carrot (Daucus carota)

Poison hemlock is a tall plant with lacy leaves and umbrella-like clusters of tiny white flowers. It has smooth, hollow stems with purple blotches and grows in sunny places like roadsides, meadows, and stream banks.

Unlike wild carrot, which has hairy stems and a dark central floret, poison hemlock has a musty odor and no flower center spot. It’s extremely toxic; just a small amount can be fatal, and even touching the sap can irritate the skin.

Water Hemlock (Cicuta spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) or wild celery (Apium spp.)

Water hemlock is a tall, branching plant with umbrella-shaped clusters of small white flowers. It grows in wet places like stream banks, marshes, and ditches, with stems that often show purple streaks or spots.

It can be confused with wild parsnip or wild celery, but its thick, hollow roots have internal chambers and release a yellow, foul-smelling sap when cut. Water hemlock is the most toxic plant in North America, and just a small amount can cause seizures, respiratory failure, and death.

False Hellebore (Veratrum viride)

Often mistaken for: Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

False hellebore is a tall plant with broad, pleated green leaves that grow in a spiral from the base, often appearing early in spring. It grows in moist woods, meadows, and along streams.

It’s commonly mistaken for ramps, but ramps have a strong onion or garlic smell, while false hellebore is odorless and later grows a tall flower stalk. The plant is highly toxic, and eating any part can cause nausea, a slowed heart rate, and even death due to its alkaloids that affect the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Death Camas (Zigadenus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild onion or wild garlic (Allium spp.)

Death camas is a slender, grass-like plant that grows from underground bulbs and is found in open woods, meadows, and grassy hillsides. It has small, cream-colored flowers in loose clusters atop a tall stalk.

It’s often confused with wild onion or wild garlic due to their similar narrow leaves and habitats, but only Allium plants have a strong onion or garlic scent, while death camas has none. The plant is extremely poisonous, especially the bulbs, and even a small amount can cause nausea, vomiting, a slowed heartbeat, and potentially fatal respiratory failure.

Buckthorn Berries (Rhamnus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Elderberries (Sambucus spp.)

Buckthorn is a shrub or small tree often found along woodland edges, roadsides, and disturbed areas. It produces small, round berries that ripen to dark purple or black and usually grow in loose clusters.

These berries are sometimes mistaken for elderberries and other wild fruits, which also grow in dark clusters, but elderberries form flat-topped clusters on reddish stems while buckthorn berries are more scattered. Buckthorn berries are unsafe to eat as they contain compounds that can cause cramping, vomiting, and diarrhea, and large amounts may lead to dehydration and serious digestive problems.

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Mayapple is a low-growing plant found in shady forests and woodland clearings. It has large, umbrella-like leaves and produces a single pale fruit hidden beneath the foliage.

The unripe fruit resembles a small green grape, causing confusion with wild grapes, which grow in woody clusters on vines. All parts of the mayapple are toxic except the fully ripe, yellow fruit, which is only safe in small amounts. Eating unripe fruit or other parts can lead to nausea, vomiting, and severe dehydration.

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Virginia creeper is a fast-growing vine found on fences, trees, and forest edges. It has five leaflets per stem and produces small, bluish-purple berries from late summer to fall.

It’s often confused with wild grapes since both are climbing vines with similar berries, but grapevines have large, lobed single leaves and tighter fruit clusters. Virginia creeper’s berries are toxic to humans and contain oxalate crystals that can cause nausea, vomiting, and throat irritation.

Castor Bean (Ricinus communis)

Often mistaken for: Wild rhubarb (Rumex spp. or Rheum spp.)

Castor bean is a bold plant with large, lobed leaves and tall red or green stalks, often found in gardens, along roadsides, and in disturbed areas in warmer regions in the US. Its red-tinged stems and overall size can resemble wild rhubarb to the untrained eye.

Unlike rhubarb, castor bean plants produce spiny seed pods containing glossy, mottled seeds that are extremely toxic. These seeds contain ricin, a deadly compound even in small amounts. While all parts of the plant are toxic, the seeds are especially dangerous and should never be handled or ingested.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

How to Get the Best Results Foraging

Safety should always come first when it comes to foraging. Whether you’re in a rural forest or a suburban greenbelt, knowing how to harvest wild foods properly is a key part of staying safe and respectful in the field.

Always Confirm Plant ID Before You Harvest Anything

Knowing exactly what you’re picking is the most important part of safe foraging. Some edible plants have nearly identical toxic lookalikes, and a wrong guess can make you seriously sick.

Use more than one reliable source to confirm your ID, like field guides, apps, and trusted websites. Pay close attention to small details. Things like leaf shape, stem texture, and how the flowers or fruits are arranged all matter.

Not All Edible Plants Are Safe to Eat Whole

Just because a plant is edible doesn’t mean every part of it is safe. Some plants have leaves, stems, or seeds that can be toxic if eaten raw or prepared the wrong way.

For example, pokeweed is only safe when young and properly cooked, while elderberries need to be heated before eating. Rhubarb stems are fine, but the leaves are poisonous. Always look up which parts are edible and how they should be handled.

Avoid Foraging in Polluted or Contaminated Areas

Where you forage matters just as much as what you pick. Plants growing near roads, buildings, or farmland might be coated in chemicals or growing in polluted soil.

Even safe plants can take in harmful substances from the air, water, or ground. Stick to clean, natural areas like forests, local parks that allow foraging, or your own yard when possible.

Don’t Harvest More Than What You Need

When you forage, take only what you plan to use. Overharvesting can hurt local plant populations and reduce future growth in that area.

Leaving plenty behind helps plants reproduce and supports wildlife that depends on them. It also ensures other foragers have a chance to enjoy the same resources.

Protect Yourself and Your Finds with Proper Foraging Gear

Having the right tools makes foraging easier and safer. Gloves protect your hands from irritants like stinging nettle, and a good knife or scissors lets you harvest cleanly without damaging the plant.

Use a basket or breathable bag to carry what you collect. Plastic bags hold too much moisture and can cause your greens to spoil before you get home.

This forager’s toolkit covers the essentials for any level of experience.

Watch for Allergic Reactions When Trying New Wild Foods

Even if a wild plant is safe to eat, your body might react to it in unexpected ways. It’s best to try a small amount first and wait to see how you feel.

Be extra careful with kids or anyone who has allergies. A plant that’s harmless for one person could cause a reaction in someone else.

Check Local Rules Before Foraging on Any Land

Before you start foraging, make sure you know the rules for the area you’re in. What’s allowed in one spot might be completely off-limits just a few miles away.

Some public lands permit limited foraging, while others, like national parks, usually don’t allow it at all. If you’re on private property, always get permission first.

Where to Find Forageables in the State

There is a range of foraging spots where edible plants grow naturally and often in abundance:

| Plant | Locations in California Where It Can Be Found and Foraged |

| Miner’s Lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata) | Mendocino National Forest, Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park, Angeles National Forest |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | Los Padres National Forest, Tahoe National Forest, Cleveland National Forest |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | Big Basin Redwoods State Park, Humboldt Redwoods State Park, Eldorado National Forest |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Point Reyes National Seashore, San Bernardino National Forest |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | Sierra National Forest, Russian River area, Yosemite National Park (outside developed areas) |

| Wild Mustard (Brassica rapa, Brassica nigra) | Marin Headlands, Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area |

| Mallow (Malva neglecta, Malva parviflora) | Angeles National Forest, Los Padres National Forest, Golden Gate National Recreation Area |

| Sow Thistle (Sonchus oleraceus) | Napa-Sonoma Marshes Wildlife Area, San Luis Reservoir State Recreation Area, Cuyamaca Rancho State Park |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | San Bernardino National Forest, Sequoia National Forest, Tahoe National Forest |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis spp.) | Redwood National and State Parks, Big Basin Redwoods State Park, Armstrong Redwoods State Natural Reserve |

| Amaranth (Amaranthus retroflexus, A. palmeri) | Sacramento River National Wildlife Refuge, Carrizo Plain National Monument, Modoc National Forest |

| Wild Onion (Allium spp.) | Inyo National Forest, Lassen National Forest, Klamath National Forest |

| Yampah (Perideridia spp.) | Lassen National Forest, Sierra National Forest, Six Rivers National Forest |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | Cosumnes River Preserve, Point Reyes National Seashore, Mendocino National Forest |

| Northern California Black Walnut (Juglans hindsii) | Putah Creek Wildlife Area, Cache Creek Natural Area, Sacramento River National Wildlife Refuge |

| Oak (Quercus spp.) | Cleveland National Forest, Eldorado National Forest, Los Padres National Forest |

| Pinyon Pine (Pinus monophylla) | Inyo National Forest, El Paso Mountains Wilderness, San Bernardino National Forest (higher elevations) |

| Gray Pine (Pinus sabiniana) | Sierra Foothills, Mendocino National Forest, Lake Berryessa area |

| Manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.) | San Bernardino National Forest, Cleveland National Forest, Los Padres National Forest |

| Blue Elderberry (Sambucus nigra ssp. caerulea) | Lassen Volcanic National Park, Tahoe National Forest, Angeles National Forest |

| Toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia) | Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, Big Sur area (Los Padres National Forest), Mount Diablo State Park |

| Wild Grape (Vitis californica) | Sacramento River corridor, Napa River Ecological Reserve, Butte Creek Ecological Preserve |

| California Blackberry (Rubus ursinus) | Redwood National and State Parks, Point Reyes National Seashore, Humboldt Redwoods State Park |

| Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) | Six Rivers National Forest, Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Lassen National Forest |

| Currant (Ribes spp.) | Tahoe National Forest, Angeles National Forest, Cleveland National Forest |

| Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia spp.) | Joshua Tree National Park, Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, Carrizo Plain National Monument |

| California Poppy (Eschscholzia californica) | Antelope Valley California Poppy Reserve, Carrizo Plain National Monument, Cuyamaca Rancho State Park |

| Nasturtium (Tropaeolum majus) | Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Santa Cruz Mountains, Marin Headlands |

| Wild Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) | Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Santa Barbara area (coastal), Point Reyes National Seashore |

| Wild Radish (Raphanus sativus) | Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, Santa Monica Mountains, Elkhorn Slough Reserve |

| California Bay Laurel (Umbellularia californica) | Big Basin Redwoods State Park, Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park, Sonoma Coast State Park |

| Pine (Pinus spp.) | Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Inyo National Forest, Sierra National Forest |

Peak Foraging Seasons

Different edible plants grow at different times of year, depending on the season and weather. Timing your search makes all the difference.

Spring

Spring brings a fresh wave of wild edible plants as the ground thaws and new growth begins:

| Edible Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| California Poppy (Eschscholzia californica) | March – May | Mild temperatures after winter rains |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | March – June | Warm days with consistent soil moisture |

| Miner’s Lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata) | February – May | Cool, moist weather after winter rains |

| Nasturtium (Tropaeolum majus) | March – May | Cool to mild, moist conditions |

| Sow Thistle (Sonchus oleraceus) | March – June | Mild temperatures, moist soil |

| Wild Mustard (Brassica rapa, Brassica nigra) | February – May | Cool to warm, especially after rain |

| Wild Onion (Allium spp.) | March – May | Cool to mild weather, moist soil |

| Wild Radish (Raphanus sativus) | March – May | Cool to warm, disturbed ground after rain |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis spp.) | February – May | Cool and damp, shady areas after rain |

| Yampah (Perideridia spp.) | April – July | Mild temperatures, moist meadows and slopes |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | March – May, September – November | Mild temperatures, moist ground |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | March – June, September – November | Cool, very moist or near freshwater streams |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | March – August | Warm weather, wet conditions in marshes |

| Mallow (Malva neglecta, Malva parviflora) | March – August | Warm weather with occasional moisture |

Summer

Summer is a peak season for foraging, with fruits, flowers, and greens growing in full force:

| Edible Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Amaranth (Amaranthus retroflexus, A. palmeri) | June – September | Hot, dry to moderately moist conditions |

| Blue Elderberry (Sambucus nigra ssp. caerulea) | June – August | Warm, dry conditions after spring rains |

| California Blackberry (Rubus ursinus) | June – August | Warm, moist conditions after spring rains |

| Currant (Ribes spp.) | June – August | Warm days, some moisture in the soil |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | May – September | Warm to hot, moderate soil moisture |

| Manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.) | July – September | Hot, dry summers during fruit ripening |

| Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia spp.) | June – September | Hot, dry desert or scrubland weather |

| Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) | June – August | Cool, moist areas, especially after rain |

| Wild Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) | June – October | Warm, dry conditions along roadsides |

Fall

As temperatures drop, many edible plants shift underground or produce their last harvests:

| Edible Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Gray Pine (Pinus sabiniana) | September – November | Warm, dry conditions |

| Northern California Black Walnut (Juglans hindsii) | September – November | Dry, late summer into early fall conditions |

| Oak (Quercus spp.) | September – November | Dry, warm to cool weather during acorn drop |

| Pine (Pinus spp.) | September – November | Dry, warm to cool conditions during cone drop |

| Pinyon Pine (Pinus monophylla) | September – October | Dry, warm weather before winter storms |

| California Bay Laurel (Umbellularia californica) | October – February | Cool, moist coastal or foothill weather |

| Wild Grape (Vitis californica) | August – October | Hot, dry late summer into early fall |

Winter

Winter foraging is limited but still possible, with hardy plants and preserved growth holding on through the cold:

| Edible Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia) | November – January | Cool, dry to slightly moist weather |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | December – April | Cool, moist, often after rain |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.