Walking through Washington’s woods feels like stepping into nature’s grocery store. Morel mushrooms pop up after spring rains while chanterelles show their golden caps in fall. Sweet berries hang from bushes during summer months, free for the picking.

The coast brings its own bounty with clams buried in sandy beaches and mussels clinging to rocky shores. Seaweed washes up with each tide, offering nutritious additions to your dinner table. These ocean treats make beach walks even more rewarding.

Mountain areas provide special finds, including wild onions and alpine berries. Pine nuts can be gathered from certain cones if you visit at the right time. Many edible plants grow at higher elevations during brief summer seasons.

Learning to forage connects you to Washington’s land in ways shopping never will. Your meals become adventures, and your hikes turn into treasure hunts.

What We Cover In This Article:

- What Makes Foreageables Valuable

- Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

- The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

- Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

- When to Forage for Maximum Value

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

What Makes Foreageables Valuable

Some wild plants, mushrooms, and natural ingredients can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re selling them or using them at home, their worth often comes down to a few key things:

The Scarcer the Plant, the Higher the Demand

Some valuable forageables only show up for a short time each year, grow in hard-to-reach areas, or are very difficult to cultivate. That kind of rarity makes them harder to find and more expensive to buy.

Morels, truffles, and ramps are all good examples of this. They’re popular, but limited access and short growing seasons mean people are often willing to pay more.

A good seasonal foods guide can help you keep track of when high-value items appear.

High-End Dishes Boost the Value of Ingredients

Wild ingredients that are hard to find in stores often catch the attention of chefs and home cooks. When something unique adds flavor or flair to a dish, it quickly becomes more valuable.

Truffles, wild leeks, and edible flowers are prized for how they taste and look on a plate. As more people try to include them in special meals, the demand—and the price—tends to rise.

You’ll find many of these among easy-to-identify wild mushrooms or herbs featured in fine dining.

Medicinal and Practical Uses Drive Forageable Prices Up

Plants like ginseng, goldenseal, and elderberries are often used in teas, tinctures, and home remedies. Their value comes from how they support wellness and are used repeatedly over time.

These plants are not just ingredients for cooking. Because people turn to them for ongoing use, the demand stays steady and the price stays high.

The More Work It Takes to Harvest, the More It’s Worth

Forageables that are hard to reach or tricky to harvest often end up being more valuable. Some grow in dense forests, need careful digging, or have to be cleaned and prepared before use.

Matsutake mushrooms are a good example, because they grow in specific forest conditions and are hard to spot under layers of leaf litter. Wild ginger and black walnuts, meanwhile, both require extra steps for cleaning and preparation before they can be used or sold.

All of that takes time, effort, and experience. When something takes real work to gather safely, buyers are usually willing to pay more for it.

Foods That Keep Well Are More Valuable to Buyers

Some forageables, like dried morels or elderberries, can be stored for months without losing their value. These longer-lasting items are easier to sell and often bring in more money over time.

Others, like wild greens or edible flowers, have a short shelf life and need to be used quickly. Many easy-to-identify wild greens and herbs are best when fresh, but can be dried or preserved to extend their usefulness.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

When you’re foraging for high-value plants, mushrooms, or other wild ingredients, every decision matters. Whether you’re selling at a farmers market or stocking your own pantry, simple mistakes can make your harvest less valuable or even completely worthless.

Harvesting at the Wrong Time

Harvesting at the wrong time can turn a valuable find into something no one wants. Plants and mushrooms have a short window when they’re at their best, and missing it means losing quality.

Morels, for example, shrink and dry out quickly once they mature, which lowers their weight and price. Overripe berries bruise in the basket and spoil fast, making them hard to store or sell.

Improper Handling After Harvest

Rough handling can ruin even the most valuable forageables. Crushed mushrooms, wilted greens, and dirty roots lose both their appeal and their price.

Use baskets or mesh bags to keep things from getting smashed and let air circulate. Keeping everything cool and clean helps your harvest stay fresh and look better for longer.

This is especially important for delicate items like wild roots and tubers that need to stay clean and intact.

Skipping Processing Steps

Skipping basic processing steps can cost you money. A raw harvest may look messy, spoil faster, or be harder to use.

For example, chaga is much more valuable when dried and cut properly. Herbs like wild mint or nettle often sell better when bundled neatly or partially dried. If you skip these steps, you may end up with something that looks unappealing or spoils quickly.

Collecting from the Wrong Area

Harvesting in the wrong place can ruin a good find. Plants and mushrooms pulled from roadsides or polluted ground may be unsafe, no matter how fresh they look.

Buyers want to know their food comes from clean, responsible sources. If a spot is known for overharvesting or damage, it can make the whole batch less appealing.

These suburbia foraging tips can help you find overlooked spots that are surprisingly safe and productive.

Not Knowing the Market

A rare plant isn’t valuable if nobody wants to buy it. If you gather in-demand species like wild ramps or black trumpets, you’re more likely to make a profit. Pay attention to what chefs, herbalists, or vendors are actually looking for.

Foraging with no plan leads to wasted effort and unsold stock. Keeping up with demand helps you bring home a profit instead of a pile of leftovers.

You can also brush up on foraging for survival strategies to identify the most versatile and useful wild foods.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

Some of the most sought-after wild plants and fungi here can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re foraging for profit or personal use, these are the ones worth paying attention to:

Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus)

Oyster mushrooms grow in shelf-like clusters on dead trees with fan-shaped caps that look like oyster shells. Their color ranges from white to gray, with gills running down the short stem. When cooked, they have a mild, slightly sweet flavor.

To identify oysters, look for gills that run down the stem and check that they grow on wood, not soil. True oysters have white to lilac spore prints. The entire mushroom is edible, though larger stems can be tough.

After rain, experienced foragers can find large clusters, making them a profitable find in the woods. Restaurants pay good prices for wild oysters because they’re packed with protein and B vitamins.

Chanterelle Mushroom (Cantharellus spp.)

Chanterelles light up the forest floor with their bright golden-yellow color and trumpet shape. Instead of flat gills, they have blunt, ridge-like folds that run down the stem. They smell fruity like apricots and taste peppery with a hint of sweetness.

You can eat the whole chanterelle, and bugs rarely damage them because of natural pest-fighting compounds. False chanterelles have thin, true gills and lack the fruity smell.

These mushrooms can’t be farmed because they need to grow with certain trees. This makes them valuable to foragers since chefs will pay top dollar for their unique flavor that can’t be found in grocery stores.

Matsutake (Tricholoma matsutake)

Matsutake mushrooms have firm white flesh and brown caps that get darker as they age. Their strong spicy smell combines cinnamon, pine, and candy-like notes. They often grow partly underground, pushing up the soil before fully emerging.

Look for the veil that connects the stem to the cap edge when young, along with the unique smell. Other similar mushrooms in the same family don’t have this powerful aroma.

In Japan, these mushrooms can cost hundreds of dollars per pound. Their special place in Japanese cooking and decreasing numbers in the wild have made them very expensive. Foragers who can find them can earn good money from their distinct flavor.

Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica)

Stinging nettle is also known as burn weed or devil leaf, and it definitely earns those names. The tiny hairs on its leaves and stems can leave a painful, tingling rash if you brush against it raw, so always wear gloves when handling it.

Once it’s cooked or dried, those stingers lose their punch, and the leaves turn mild and slightly earthy in flavor. The texture softens too, making it a solid substitute for spinach in soups, pastas, or even as a simple sauté.

The young leaves and tender tops are what you want to collect. Avoid the tough lower stems and older leaves, which can be gritty or unpleasant to chew.

Some people confuse stinging nettle with purple deadnettle or henbit, but those don’t sting and have more rounded, fuzzy leaves. If the plant doesn’t make your skin react, it’s not stinging nettle.

Fiddlehead Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris)

Fiddleheads are the young, curled fronds of the ostrich fern that look like the scroll on a violin. These bright green coils have a deep groove on the inside of their smooth stem. Their taste mixes flavors of asparagus and artichoke.

Only ostrich fern fiddleheads are commonly eaten in North America. You can tell them from other ferns by their smooth stems, brown papery scales, and U-shaped groove. Always cook them thoroughly to avoid stomach upset.

The very short spring harvest period of just 1-2 weeks makes fiddleheads special on restaurant menus. Their unique shape and flavor create high demand since they can’t be grown commercially like farm vegetables.

Miner’s Lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata)

Miner’s lettuce, also known as Indian lettuce and winter purslane, has round, cup-shaped leaves that almost look like they are threaded through the stem. Tiny white flowers often bloom right in the center of the leaf, giving it a distinctive, easy-to-spot look if you are paying attention.

The leaves and stems are edible and have a crisp, tender texture with a mild, slightly sweet flavor. Some people describe the taste as a little like spinach but even fresher and lighter when eaten raw.

You can toss miner’s lettuce straight into salads, blend it into smoothies, or lightly sauté it for a simple side dish. It also holds up well when added to sandwiches or wrapped in tortillas if you want a bit of fresh crunch.

While it is generally safe to eat, it is important to avoid confusing miner’s lettuce with toxic lookalikes like young spurge plants, which have a milky sap if snapped. Always double-check that the stems are smooth and the flowers are small and white before harvesting anything to eat.

Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus)

Thimbleberry is a native shrub that produces bright red, hollow berries with a seedy, melt-in-your-mouth texture. You can eat them raw, but they’re often used in jams and desserts because they fall apart easily.

The leaves are soft and wide with five deep lobes, unlike the more jagged or compound leaves of black raspberry or blackberry. Be cautious of misidentifying it with red raspberry, which has thorny stems and smaller, firmer fruit.

There’s no commercial thimbleberry farming because the fruit is too fragile to ship.

Thimbleberry has no thorns, which makes harvesting less painful compared to other berries in the same family. The plant’s white, five-petaled flowers are another clue you’ve found the right thing.

Don’t eat the leaves or stems; they aren’t toxic, but they’re not used for food.

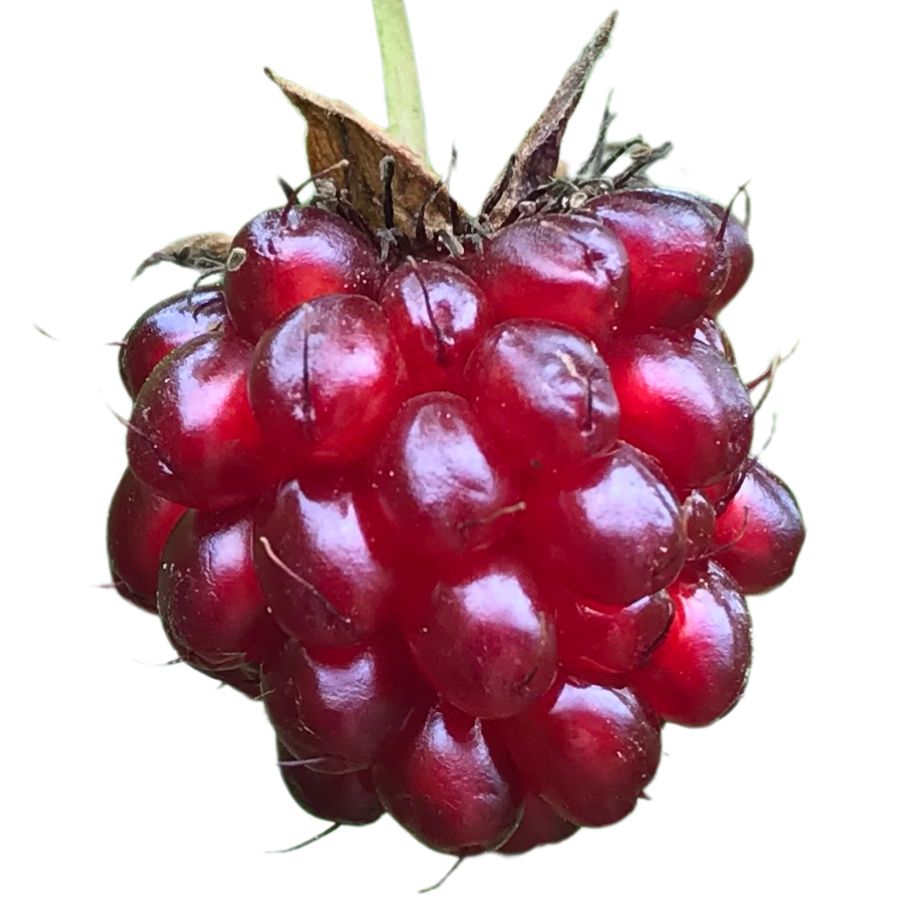

Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis)

Salmonberries are bright pink to red berries that are a sweet, tangy treat. They are similar to raspberries but have a firmer texture and a more pronounced sweetness with a slight tart finish.

Although the berries are safe to eat, it’s important to avoid consuming the leaves, as they can lead to mild stomach irritation.

Fresh salmonberries are often enjoyed on their own, mixed into yogurt, or turned into homemade preserves like jam. The fruit also freezes well, which allows you to enjoy the harvest long after picking.

Salmonberry bushes can be found along the edges of wetlands, and their thorns can make picking them a bit of a challenge. However, the effort is well worth it for those who enjoy the rich taste and versatility of this unique berry.

Huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum)

Huckleberries grow on small shrubs with oval, toothed leaves. The dark purple to black berries pack an intense flavor that combines sweetness with a tangy punch. Unlike cultivated blueberries, wild huckleberries have 10 large seeds that give them a distinctive crunch.

Look for bell-shaped flowers in spring and single berries on stems rather than clusters. They’re sometimes confused with toxic baneberry, but baneberries grow in clusters and have white berries with black dots.

Only the berries are edible, not the leaves or stems. Huckleberries can’t be commercially grown, making them valuable at farmers markets and restaurants.

Their high antioxidant content exceeds blueberries, adding to their appeal for health benefits. The unique flavor makes them perfect for jams, pies, and syrups.

Wild Strawberry (Fragaria vesca)

Wild strawberries carpet forest floors with their three-parted leaves and white five-petaled flowers. The tiny red fruits may be small, but they contain more flavor than any store-bought variety. Their sweet aroma fills the air when a patch is ripe.

The entire plant offers benefits: fruits for eating, leaves for vitamin C-rich tea, and runners for growing new plants. Wild strawberries present their fruit facing outward rather than hanging down like mock strawberries.

Be careful not to confuse them with mock strawberries (Potentilla indica), which have yellow flowers and tasteless fruits.

Blackcap Raspberry (Rubus leucodermis)

Blackcap raspberries feature arching canes covered with a white waxy coating that looks bluish in sunlight. The berries ripen from red to deep purple-black and maintain a hollow core when picked. Their flavor balances sweetness and tartness with subtle floral hints.

Ripe fruits pull away easily, leaving their central core behind, unlike blackberries which keep their core when picked. Wear gloves when harvesting to protect yourself from the thorny canes.

These berries contain powerful antioxidants that give them deep color and health benefits. Some compounds in blackcaps are being studied for fighting cancer.

Their fragility and short shelf life mean they’re mostly wild-harvested. The striking juice makes natural dyes and adds flavor to syrups and jams that sell well at local markets.

Hazelnut (Corylus cornuta)

Hazelnuts come from multi-stemmed shrubs with heart-shaped, doubly toothed leaves. The nuts develop inside distinctive husks with long, beak-like extensions. These wild relatives of commercial filberts offer rich, sweet flavor that gets even better when roasted.

Ripe nuts show themselves when husks turn from green to brown. Watch out for tiny irritating hairs on some husks when harvesting.

Squirrels often beat humans to finding these protein-rich treats. Only the kernel inside is edible, not the husk or shell.

Properly dried hazelnuts stay fresh for months, providing valuable fats and nutrients during winter. Their versatility in cooking makes them sought-after for specialty chocolates, baked goods, and oils that command premium prices.

Wild Onion (Allium cernuum)

Wild onions stand out with their drooping flower heads in pink to lavender colors. The umbrella-shaped clusters sit atop hollow, tube-like leaves growing from small bulbs. Breaking any part releases an unmistakable onion smell.

Both bulbs and greens are edible, with bulbs providing sharp flavor and greens offering milder taste like chives. The pretty flowers make tasty additions to salads.

The onion smell when crushed is your safety test; toxic lookalikes like death camas never smell like onions. This simple test keeps foragers safe.

Wild onions contain compounds that historically helped preserve food and treat illness. Chefs prize them for garnishing expensive dishes, creating steady demand despite their small size compared to grocery store varieties.

Camas Bulb (Camassia quamash)

Camas produces star-shaped blue to purple flowers that grow in clusters on tall stalks. The plants grow from underground bulbs that Native American tribes across the Pacific Northwest relied on as a main food source for thousands of years. When properly cooked, these starchy bulbs taste sweet like baked pears.

Look for grass-like leaves with no center rib and the star-shaped blue flowers. Never harvest without seeing the flowers first, as death camas has similar leaves but white flowers and is deadly poisonous.

Only the bulb is edible after slow cooking, which turns the indigestible inulin into sweet sugars. Traditional cooking involves pit roasting for 24-48 hours.

The cultural importance and unique sweet flavor make camas popular among people interested in traditional foods. Some restaurants now feature them in special dishes.

Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia)

Serviceberries grow in clusters on shrubs or small trees with smooth gray bark. The purple-red fruits follow white spring flowers and taste like a mix of blueberry, cherry, and almond. Each berry has a star-shaped crown on the bottom.

You can eat the whole fruit, including the small seeds that add an almond flavor note. The berries taste great fresh, dried like raisins, or made into jams and pies.

Serviceberries have no dangerous lookalikes, making them safe for new foragers. They might be confused with chokecherries, which grow in hanging clusters and have larger pits.

These berries contain high amounts of iron, protein, and antioxidants. Since they’re rarely grown commercially and spoil quickly after picking, finding them in stores is nearly impossible, making them valuable for foragers.

Beech Nuts (Fagus grandifolia)

Beech nuts hide inside spiky husks that split open when ripe to reveal brown, triangular nuts. They grow on tall trees with smooth, gray bark that stands out in the forest. The small kernels inside taste sweet and rich, similar to hazelnuts but with their own unique flavor.

You can spot American beech trees by their smooth bark and thin, pointed cigar-shaped buds that remain through winter. Look for nuts on the ground after they fall from the tree.

Only the kernel inside the thin shell is edible. The husks contain substances that can upset your stomach, so avoid eating those.

These nuts are packed with healthy fats and protein. Squirrels, deer, and bears love them too, making competition fierce. Their rich taste makes them worth the effort to collect, though gathering enough requires patience.

Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

Some parts of the state are better than others when it comes to finding valuable wild plants and mushrooms. Here are the different places where you’re most likely to have luck:

| Plant | Locations |

|---|---|

| Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) | – Capitol State Forest – Green River Natural Resources Area – Snoqualmie River Valley woodlands |

| Chanterelle Mushroom (Cantharellus spp.) | – Tiger Mountain State Forest – Yacolt Burn State Forest – Chehalis River hillsides near Adna |

| Matsutake (Tricholoma matsutake) | – Ahtanum State Forest – Indian Heaven region near Trout Lake (non-federal edges) – Colville area pine woods |

| Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) | – Sammamish River Trail edges – Woodard Bay Natural Resources Area – Puyallup River greenbelt |

| Fiddlehead Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) | – Nisqually Valley streambanks – Wallace Falls State Park area – Twin Harbors near Grayland marshes |

| Miner’s Lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata) | – Bellingham hillside trails – Bainbridge Island woodlots – Fort Steilacoom Park wooded areas |

| Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) | – Rattlesnake Ledge area – Larrabee State Park surroundings – Fort Borst Park woodland edge in Centralia |

| Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis) | – Discovery Park wooded trails in Seattle – Kitsap Peninsula ravines – Elwha River greenways near Port Angeles |

| Huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum) | – Mount Spokane lower slopes – Bluewood area forests near Dayton – Kettle Range clearings |

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria vesca) | – San Juan Island meadows – Camas Prairie near Pomeroy – Millersylvania State Park edge fields |

| Blackcap Raspberry (Rubus leucodermis) | – Green River Gorge area – Columbia Plateau bluffs near Kahlotus – Okanogan Valley trails |

| Hazelnut (Corylus cornuta) | – Cedar River Trail banks – Tumwater Falls Park woods – Methow Valley stream corridors |

| Wild Onion (Allium cernuum) | – Selah Cliffs area – Manastash Ridge near Ellensburg – Little Spokane River hillsides |

| Camas Bulb (Camassia quamash) | – Lacamas Prairie Natural Area – Mima Mounds Natural Area Preserve – Fort Vancouver historic prairie edges |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia) | – Yakima River Canyon near Selah – Turnbull-area shrublands – Lopez Island slopes |

| Beech Nuts (Fagus grandifolia) | – Northern Kitsap Peninsula – Point Defiance older forest groves – Fort Flagler forest edges |

When to Forage for Maximum Value

Every valuable wild plant or mushroom has its season. Here’s a look at the best times for harvest:

| Plants | Valuable Parts | Best Harvest Season |

|---|---|---|

| Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) | Fruit bodies | September – November |

| Chanterelle Mushroom (Cantharellus spp.) | Fruit bodies | August – October |

| Matsutake (Tricholoma matsutake) | Fruit bodies | September – November |

| Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) | Young leaves, shoots | March – May |

| Fiddlehead Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) | Young coiled fronds (fiddleheads) | April – May |

| Miner’s Lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata) | Tender leaves, stems | February – April |

| Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) | Ripe berries, young shoots | June – July (berries), April – May (shoots) |

| Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis) | Ripe berries, young shoots | May – June (berries), March – April (shoots) |

| Huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum) | Ripe berries | July – September |

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria vesca) | Ripe berries, young leaves | May – July (berries), April – May (leaves) |

| Blackcap Raspberry (Rubus leucodermis) | Ripe berries | June – July |

| Hazelnut (Corylus cornuta) | Nuts | September – October |

| Wild Onion (Allium cernuum) | Bulbs, leaves, flowers | April – June (leaves and flowers), September – October (bulbs) |

| Camas Bulb (Camassia quamash) | Bulbs | May – June (after flowering) |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia) | Ripe berries | June – July |

| Beech Nuts (Fagus grandifolia) | Nuts | October – November |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.