Tennessee offers a world of natural foods waiting in its forests, fields, and mountains. The state’s diverse landscape creates perfect growing conditions for many valuable plants and fungi. Learning to spot these wild treasures can be both fun and rewarding.

From morel mushrooms in spring to wild berries in summer, our state has seasonal treats to gather year-round. Local knowledge helps foragers find these special plants at just the right time.

Many Tennessee families have passed down foraging traditions through generations. These skills connect people to the land and provide tasty, free food. Foraging also teaches us about nature’s cycles and the importance of taking only what we need.

Safety matters most when gathering wild foods in Tennessee. Learning to identify plants correctly prevents mistakes with look-alikes.

With some basic knowledge and respect for nature, you can enjoy finding valuable plants across Tennessee. The hills and hollows of our beautiful state contain foods that grocery stores simply don’t carry. Your next hiking trip might lead to a delicious wild meal that costs nothing but time spent outdoors.

What We Cover In This Article:

- What Makes Foreageables Valuable

- Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

- The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

- Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

- When to Forage for Maximum Value

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

What Makes Foreageables Valuable

Some wild plants, mushrooms, and natural ingredients can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re selling them or using them at home, their worth often comes down to a few key things:

The Scarcer the Plant, the Higher the Demand

Some valuable forageables only show up for a short time each year, grow in hard-to-reach areas, or are very difficult to cultivate. That kind of rarity makes them harder to find and more expensive to buy.

Morels, truffles, and ramps are all good examples of this. They’re popular, but limited access and short growing seasons mean people are often willing to pay more.

A good seasonal foods guide can help you keep track of when high-value items appear.

High-End Dishes Boost the Value of Ingredients

Wild ingredients that are hard to find in stores often catch the attention of chefs and home cooks. When something unique adds flavor or flair to a dish, it quickly becomes more valuable.

Truffles, wild leeks, and edible flowers are prized for how they taste and look on a plate. As more people try to include them in special meals, the demand—and the price—tends to rise.

You’ll find many of these among easy-to-identify wild mushrooms or herbs featured in fine dining.

Medicinal and Practical Uses Drive Forageable Prices Up

Plants like ginseng, goldenseal, and elderberries are often used in teas, tinctures, and home remedies. Their value comes from how they support wellness and are used repeatedly over time.

These plants are not just ingredients for cooking. Because people turn to them for ongoing use, the demand stays steady and the price stays high.

The More Work It Takes to Harvest, the More It’s Worth

Forageables that are hard to reach or tricky to harvest often end up being more valuable. Some grow in dense forests, need careful digging, or have to be cleaned and prepared before use.

Matsutake mushrooms are a good example, because they grow in specific forest conditions and are hard to spot under layers of leaf litter. Wild ginger and black walnuts, meanwhile, both require extra steps for cleaning and preparation before they can be used or sold.

All of that takes time, effort, and experience. When something takes real work to gather safely, buyers are usually willing to pay more for it.

Foods That Keep Well Are More Valuable to Buyers

Some forageables, like dried morels or elderberries, can be stored for months without losing their value. These longer-lasting items are easier to sell and often bring in more money over time.

Others, like wild greens or edible flowers, have a short shelf life and need to be used quickly. Many easy-to-identify wild greens and herbs are best when fresh, but can be dried or preserved to extend their usefulness.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

When you’re foraging for high-value plants, mushrooms, or other wild ingredients, every decision matters. Whether you’re selling at a farmers market or stocking your own pantry, simple mistakes can make your harvest less valuable or even completely worthless.

Harvesting at the Wrong Time

Harvesting at the wrong time can turn a valuable find into something no one wants. Plants and mushrooms have a short window when they’re at their best, and missing it means losing quality.

Morels, for example, shrink and dry out quickly once they mature, which lowers their weight and price. Overripe berries bruise in the basket and spoil fast, making them hard to store or sell.

Improper Handling After Harvest

Rough handling can ruin even the most valuable forageables. Crushed mushrooms, wilted greens, and dirty roots lose both their appeal and their price.

Use baskets or mesh bags to keep things from getting smashed and let air circulate. Keeping everything cool and clean helps your harvest stay fresh and look better for longer.

This is especially important for delicate items like wild roots and tubers that need to stay clean and intact.

Skipping Processing Steps

Skipping basic processing steps can cost you money. A raw harvest may look messy, spoil faster, or be harder to use.

For example, chaga is much more valuable when dried and cut properly. Herbs like wild mint or nettle often sell better when bundled neatly or partially dried. If you skip these steps, you may end up with something that looks unappealing or spoils quickly.

Collecting from the Wrong Area

Harvesting in the wrong place can ruin a good find. Plants and mushrooms pulled from roadsides or polluted ground may be unsafe, no matter how fresh they look.

Buyers want to know their food comes from clean, responsible sources. If a spot is known for overharvesting or damage, it can make the whole batch less appealing.

These suburbia foraging tips can help you find overlooked spots that are surprisingly safe and productive.

Not Knowing the Market

A rare plant isn’t valuable if nobody wants to buy it. If you gather in-demand species like wild ramps or black trumpets, you’re more likely to make a profit. Pay attention to what chefs, herbalists, or vendors are actually looking for.

Foraging with no plan leads to wasted effort and unsold stock. Keeping up with demand helps you bring home a profit instead of a pile of leftovers.

You can also brush up on foraging for survival strategies to identify the most versatile and useful wild foods.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

Some of the most sought-after wild plants and fungi here can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re foraging for profit or personal use, these are the ones worth paying attention to:

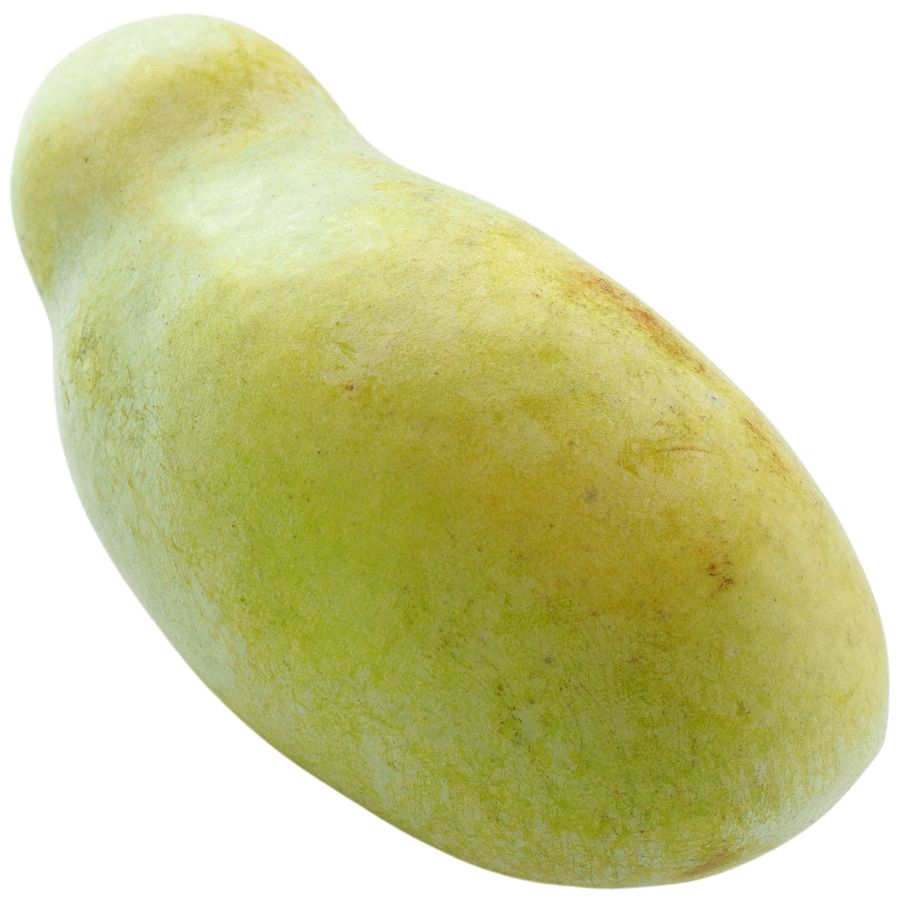

Pawpaw Fruit (Asimina triloba)

The pawpaw grows fruits that are green and shaped a little like small mangoes. Inside, the soft yellow flesh tastes like a blend of banana, mango, and melon, with a custard-like texture that melts in your mouth.

If you are comparing it to similar plants, keep in mind that young pawpaw trees can look a little like young magnolias because of their large leaves. True pawpaws grow fruits with large brown seeds tucked inside, while magnolias do not produce anything that looks or tastes similar.

You can eat the flesh straight out of the skin with a spoon, or mash it into puddings, smoothies, and even homemade ice cream. Some people also like to freeze it into cubes for later, although it does tend to brown quickly once exposed to air.

Stick to eating the soft inner flesh. Make sure not to ingest the skin and seeds of the fruit because they contain compounds that can upset your stomach.

This fruit is that it was a favorite snack of Native Americans and early explorers long before it started showing up in backyard gardens.

Black Trumpet Mushrooms (Craterellus fallax)

The trumpet-shaped, dark gray to black fungi grow in clusters on forest floors, often hidden among leaves. Their vase-like hollow form can reach 3 inches tall with wavy edges. Many foragers walk right past these camouflaged treasures, which have a rich, smoky flavor similar to black truffles.

The edible portion includes the entire mushroom. They have no poisonous look-alikes, making them relatively safe for beginning foragers.

Black trumpets tend to grow in the same spots year after year, particularly near oak and beech trees. Their dark color helps them blend perfectly with the forest floor.

These mushrooms are prized by chefs for their intense flavor that enhances soups, sauces, and egg dishes. Once dried, their flavor becomes even more concentrated. Unlike many other wild mushrooms, black trumpets rarely host bugs or worms.

Wild Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

Known as wild ramp, leek, or ramson, this flavorful plant is famous for its broad green leaves and slender white stems. It grows low to the ground and gives off a strong onion-like scent when bruised, which can help you tell it apart from toxic lookalikes like lily of the valley.

If you give it a taste, you will notice a bold mix of onion and garlic flavors, with a tender texture that softens even more when cooked. People often sauté the leaves and stems, pickle the bulbs, or blend them into pestos and soups.

The entire plant can be used for cooking, but the leaves and bulbs are the most prized parts. It is important not to confuse it with similar-looking plants that do not have the signature onion smell when crushed.

Wild leek populations have declined in some areas because of overharvesting, so it is a good idea to only take a few from any given patch. When harvested thoughtfully, these vibrant greens can add a punch of flavor to just about anything you make.

Persimmons (Diospyros virginiana)

Persimmon, sometimes called American persimmon or common persimmon, grows as a small tree with rough, blocky bark and oval-shaped leaves. The fruit looks like a small, flattened tomato and turns a deep orange or reddish color when ripe.

If you bite into an unripe persimmon, you will quickly notice an extremely astringent, mouth-drying effect. A ripe persimmon, on the other hand, tastes sweet, rich, and custard-like, with a soft and jelly-like texture inside.

You can eat persimmons fresh once they are fully ripe, or you can cook them down into puddings, jams, and baked goods. Some people also mash and freeze the pulp to use later for pies, breads, and sauces.

Wild persimmons can sometimes be confused with black nightshade berries, but nightshade fruits are much smaller, grow in clusters, and stay dark purple or black. Only the ripe fruit of the persimmon tree should be eaten; the seeds and the unripe fruit are not edible.

Appalachian Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus lateritius)

Bright golden-orange in color, these trumpet-shaped fungi have a fruity aroma reminiscent of apricots. Their meaty texture and slightly peppery taste make them a favorite among mushroom enthusiasts. Unlike store-bought varieties, wild chanterelles offer a complex flavor that can’t be cultivated commercially.

These fungi grow in symbiotic relationships with hardwood trees, particularly oak. The caps have ridges rather than true gills that run down the stem.

False chanterelles can be distinguished by their true gills and duller orange color. The poisonous jack-o-lantern mushroom also looks similar, but grows on wood rather than soil.

Chanterelles work well in cream sauces, risottos, and egg dishes. They retain their texture when cooked, unlike many other mushrooms that become soft.

Their value comes from their short growing season and the fact they cannot be commercially grown.

Hickory Nuts (Carya spp.)

The sweet kernels of hickory nuts are encased in thick, woody shells that split into four sections when mature. These nuts grow on tall, native trees throughout eastern North America. Each variety offers slightly different flavors, with shagbark hickory producing the sweetest and most sought-after nuts.

Hickory nuts require patience to harvest and process. The sweet inner kernel must be extracted from both the outer husk and the hard inner shell.

The edible portion is only the kernel inside. The nut meat can be eaten raw or used in baking.

What makes hickory nuts valuable is their rich, buttery flavor that surpasses even pecans. They contain healthy fats and proteins along with several minerals. Indigenous peoples once used these nuts as a dietary staple, even processing them into a nutritious milk-like drink.

Many foragers consider the effort of cracking them worthwhile for their incomparable taste.

Fiddlehead Ferns (Matteuccia struthiopteris)

Tightly coiled and resembling the scroll on a violin, these young ostrich fern shoots emerge in woodland areas. The bright green spirals are covered with papery brown scales and grow in circular clusters called “crowns.” Each fiddlehead features a distinctive deep groove running down the inside of the stem.

Only harvest ostrich fern fiddleheads, as some other fern species can be toxic. Look for the U-shaped groove on the inside of the stem and brown papery scales.

Fiddleheads need thorough cooking to remove bitter compounds and make them safe to eat. Their flavor combines aspects of asparagus, artichoke, and nuts.

Only the tightly coiled young shoots, before they unfurl into fronds, are edible. The mature fern leaves are not edible.

Their unique appearance makes them popular in high-end restaurants. Foragers value them for their brief harvest window and distinctive taste that can’t be found in cultivated vegetables.

Spicebush Berries (Lindera benzoin)

Spicebush has smooth-edged leaves that release a spicy citrus scent when crushed, and it produces clusters of red berries that grow close to the stem. Those berries, along with the young twigs and leaves, are all edible and flavorful.

The berries are especially valued for their warm, peppery kick and are often dried and ground as a seasoning. You can steep the leaves and twigs into tea or simmer them into broths.

Avoid confusing it with lookalikes like Carolina allspice, which has larger, thicker leaves and lacks the same aromatic quality. Its berries also differ in size and internal seed structure.

Spicebush has a long history of use in traditional cooking for its mild numbing effect and warming flavor. Only the berries, leaves, and tender twigs should be consumed—avoid the bark and roots.

Sassafras (Sassafras albidum)

Sassafras is a small deciduous tree with bright green leaves that feel slightly mucilaginous when crushed. You can eat the young leaves raw or dried, and they develop a unique flavor—lightly citrusy, with a smooth texture when chewed.

People use the ground leaves as a thickener in soups and stews, especially in southern recipes. The bark and roots have a stronger taste and were historically brewed into teas with a deep, spicy profile.

There’s a caution with sassafras root: it contains safrole, which has been restricted from commercial food use due to safety studies. However, using a small amount occasionally in traditional preparations is still common in home kitchens.

The tree has a sweet, clove-like scent that sets it apart when the leaves or twigs are snapped. Its closest lookalikes lack that scent and don’t have the same combination of leaf shapes on a single branch.

Wild Mint (Mentha spicata)

You’re probably familiar with the strong scent of wild mint, which comes from the essential oils concentrated in its leaves. It has square stems, lance-shaped leaves with slightly toothed edges, and pale lilac flower clusters.

The fresh leaves can be eaten raw, cooked into soups, or muddled into drinks for a crisp flavor. Expect a bright, menthol-like kick with a hint of sweetness.

False mint species like purple deadnettle grow in similar spots but lack the menthol smell and have fuzzy leaves. If the plant doesn’t smell like mint, it probably isn’t.

Stick to the leaves and younger stems for eating because the woody stalks aren’t palatable. Wild mint also holds up well when dried and stored for tea or seasoning.

Autumn Olive Berries (Elaeagnus umbellata)

With its silver-dusted leaves and small, speckled red fruits, autumn olive, also called silverberry or Japanese silverberry, has made its way into many thickets and field edges. The fruit is edible, tart, and slick-skinned, with a burst of sourness that mellows in cooked preparations.

People often turn autumn olive into jelly, sauces, or fermented beverages to tame the intense flavor. You can also dehydrate the berries into a powder for use in baked goods.

Some confuse it with Russian olive, which grows similar leaves but bears dry, yellow fruit instead. Stick to harvesting just the berries, as the rest of the plant doesn’t have any culinary use.

What makes autumn olive particularly interesting is its nitrogen-fixing ability, which helps it thrive where other plants struggle, but that same trait is also why it spreads so aggressively. Still, the fruit is safe and edible, and one of the few wild berries with such a high lycopene content.

Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus)

Jerusalem artichoke grows tall with sunflower-like blooms and has knobby underground tubers. The tubers are tan or reddish and look a bit like ginger root, though they belong to the sunflower family.

The part you’re after is the tuber, which has a nutty, slightly sweet flavor and a crisp texture when raw. You can roast, sauté, boil, or mash them like potatoes, and they hold their shape well in soups and stir-fries.

Some people experience gas or bloating after eating sunchokes due to the inulin they contain, so it’s a good idea to try a small amount first. Cooking them thoroughly can help reduce the chances of digestive discomfort.

Sunchokes don’t have many dangerous lookalikes, but it’s important not to confuse the plant with other sunflower relatives that don’t produce tubers. The above-ground part resembles a small sunflower, but it’s the knotted, underground tubers that are worth digging up.

Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

Wild bergamot has clusters of lavender-colored flowers and opposite leaves that smell like thyme when crushed. Its flavor leans herbal and minty, with a little bitterness that works well in marinades.

The flower heads are shaggy and irregular, and the plant’s square stem helps tell it apart from lookalikes like spotted horsemint.

In recipes, it’s most often dried and steeped or blended into herb mixes.

Both leaves and petals can be eaten, though most people avoid the stems. Don’t eat it in large amounts raw—it’s strong and can be overpowering.

It’s related to mint, and that shows in how fast the flavor develops when heat is applied. You’ll get the most aroma if you bruise the leaves before using them.

Wild Hopniss / Groundnut (Apios Americana)

Groundnut is also called potato bean or Indian potato, and it grows as a climbing vine with clusters of pinkish-purple flowers. The part most people go for is the underground tuber, which looks a bit like a small, knobby chain of beads.

The flavor is richer than a regular potato, with a nutty, earthy taste and a dense, almost chestnut-like texture when cooked. It holds up well in soups and stews, or you can boil and mash it like a root vegetable.

Some people slice it thin and roast it until crisp, while others slow-cook it to bring out a sweeter taste. The vine also produces beans, but the root is what’s usually eaten.

There are a few vines that resemble groundnut, but many of those don’t have the same distinctive flower clusters or tend to lack the beadlike roots. Always make sure you’re digging up the right plant before cooking it.

Toothwort Root (Cardamine concatenate)

Toothwort gets its name from the tooth-like segments of its underground rhizome. The plant produces delicate white or pink flowers in early spring before many trees leaf out. Its roots have a spicy, horseradish-like flavor that adds a pleasant kick to foods.

The edible roots can be harvested carefully without killing the plant by taking only a portion of the rhizome. When identifying toothwort, look for its distinctive palm-shaped leaves with toothed edges growing on stems about 8-12 inches tall.

Be careful not to confuse toothwort with poisonous plants in the woodland understory. The plant contains valuable nutrients and natural compounds that support immune health. Native Americans used toothwort roots both as food and medicine, particularly for respiratory conditions.

Toothwort root can be eaten raw in small amounts, pickled, or dried and ground as a mustard-like spice for soups and stews.

Devil’s Walking Stick Shoots (Aralia spinosa)

Sharp thorns cover the trunk and branches of the Devil’s Walking Stick, making it instantly recognizable in forests across eastern North America. Despite its intimidating appearance, this plant offers tender, edible young shoots in spring that taste similar to asparagus.

The plant grows as a small tree or large shrub, reaching up to 20 feet tall. The young shoots must be harvested before they develop thorns and while still tender. To prepare them, simply peel away the outer layer and cook them like asparagus.

Devil’s Walking Stick belongs to the same family as ginseng and contains similar beneficial compounds. Native American tribes used various parts of the plant for medicinal purposes. The shoots provide a good source of vitamins and minerals.

When foraging, wear thick gloves to protect yourself from the sharp thorns on mature parts of the plant.

Wild Prickly Ash Berries (Zanthoxylum americanum)

Wild Prickly Ash produces small, aromatic berries that create a unique numbing sensation when chewed. This native shrub features distinctive paired thorns along its branches and compound leaves that release a citrus scent when crushed.

The berries turn from green to red-brown when ripe in late summer. The outer husks, not the seeds inside, are the edible part used as a spice. Their flavor combines citrus and pepper notes, earning them the nickname “toothache tree” for their numbing properties.

Avoid confusing Wild Prickly Ash with similar thorny shrubs by checking for its citrus smell and the distinctive pimple-like oil glands on the leaves. The berries contain valuable essential oils that have been used in traditional medicine.

These berries can be dried and ground as a spice similar to Szechuan peppercorns, adding unique flavor to meats, soups, and sauces.

Mulberries (Morus rubra)

Mulberry trees produce juicy, sweet fruits that resemble blackberries but grow directly on the branches. Native red mulberries are particularly flavorful, with a perfect balance of sweetness and mild tartness that makes them a favorite wild treat.

The trees can grow quite tall, often reaching 30-50 feet in height. Their leaves are easily identified by their variable shapes on the same branch, sometimes lobed and sometimes not. The berries start green, then turn red, and finally darken to purple-black when fully ripe.

No poisonous lookalikes exist for mulberries in North America. The fruits are not only delicious fresh but also make excellent jams, pies, and wines. They stain fingers and clothing purple, so wear old clothes when gathering.

Mulberries offer excellent nutrition, packed with vitamin C, iron, and antioxidants. Birds love them too, so competition can be fierce when they’re in season.

Wood Nettles (Laportea canadensis)

Wood nettles grow in rich, moist woodland soils, forming patches of upright plants with serrated, opposite leaves. Unlike their relative stinging nettle, wood nettles have alternate leaves and less intense stinging hairs, though they can still cause temporary skin irritation if touched.

The stinging sensation comes from hollow hairs that inject a mix of chemicals when brushed against. Despite this defense mechanism, wood nettles are among the most nutritious wild greens available, containing high levels of protein, iron, and vitamins A and C.

Cooking or drying completely neutralizes the sting, transforming them into a spinach-like green with a richer, more complex flavor. They can be used in soups, pasta dishes, or anywhere you would use cooked spinach.

When harvesting, wear gloves and collect young plants or just the top few inches of taller plants for the most tender greens. The stems, leaves, and even seeds are all edible when properly prepared.

Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

Some parts of the state are better than others when it comes to finding valuable wild plants and mushrooms. Here are the different places where you’re most likely to have luck:

| Plant | Locations |

|---|---|

| Pawpaw Fruit (Asimina triloba) | – Duck River bottoms near Columbia – Shelby Bottoms Greenway near Nashville – Holston River area |

| Black Trumpet Mushrooms (Craterellus fallax) | – Smoky foothills near Townsend – Fall Creek Falls vicinity near Spencer – Prentice Cooper State Forest |

| Wild Ramps (Allium tricoccum) | – Cherokee National Forest – Roan Mountain lower slopes – Big Ridge area north of Knoxville |

| Persimmons (Diospyros virginiana) | – Natchez Trace near Hohenwald – Meeman-Shelby Forest – Greenbelt Park in Maryville |

| Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus lateritius) | – Hiwassee River woods near Reliance – Standing Stone State Forest – Norris Dam vicinity forest trails |

| Hickory Nuts (Carya spp.) | – Savannah area hardwood groves – Radnor Lake State Natural Area – Obion River bottoms near Union City |

| Fiddlehead Ferns (Matteuccia struthiopteris) | – Roan Creek valley – Cold Springs Hollow near Tellico Plains – Buffalo Mountain area |

| Spicebush Berries (Lindera benzoin) | – Old Stone Fort area near Manchester – Cedars of Lebanon forest edge – French Broad River corridor near Newport |

| Sassafras Root and Leaves (Sassafras albidum) | – Henry Horton State Park woodlands – Reelfoot Lake edge near Tiptonville – Lookout Mountain base near Trenton |

| Wild Mint (Mentha arvensis, Mentha spicata) | – Beaver Creek wetlands near Powell – Laurel River Lake inlet banks – Cane Creek near Cookeville |

| Autumn Olive Berries (Elaeagnus umbellata) | – Abandoned fields near Elizabethton – Columbia farmland edges – Hillsboro pastures near Tullahoma |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | – Sequatchie Valley ditch lines – Muddy Creek floodplain near Blountville – Ducktown scrublands |

| Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) | – Savage Gulf edge meadows – Fort Loudoun Lake hillsides – Ridge top prairies near Dover |

| Wild Hopniss / Groundnut (Apios americana) | – Wetlands near Fort Pillow – South Harpeth River edges near Fairview – Shallow creek banks near Pikeville |

| Toothwort Root (Cardamine concatenata) | – Shade-rich hollows near Cosby – Laurel Creek forest near Townsend – Shady groves near Wartburg |

| Devil’s Walking Stick Shoots (Aralia spinosa) | – Cedar Glades near Murfreesboro – Hill slopes near Monteagle – Forest paths near Lexington |

| Wild Prickly Ash Berries (Zanthoxylum americanum) | – Fields near Martin – Open groves near Jamestown – Bluffs near Savannah |

| Mulberries (Morus rubra) | – Wood edges near Jackson – East Nashville park trails – Cane Ridge meadows |

| Wood Nettles (Laportea canadensis) | – Moist hollows near Dayton – Hatchie River bottoms – Forked Deer River near Dyersburg |

When to Forage for Maximum Value

Every valuable wild plant or mushroom has its season. Here’s a look at the best times for harvest:

| Plants | Valuable Parts | Best Harvest Season |

|---|---|---|

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | Ripe fruit | August – September |

| Black Trumpet Mushrooms (Craterellus fallax) | Fruiting bodies | July – September |

| Wild Ramps (Allium tricoccum) | Bulbs, young leaves | Bulbs (March – April), young leaves (April – May) |

| Persimmons (Diospyros virginiana) | Ripe fruit | September – November |

| Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus lateritius) | Fruiting bodies | June – September |

| Hickory Nuts (Carya spp.) | Nuts | September – October |

| Fiddlehead Ferns (Matteuccia struthiopteris) | Young coiled fronds | April – May |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | Berries | August – September |

| Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) | Root bark, young leaves | Root bark (October – November), young leaves (April – May) |

| Wild Mint (Mentha arvensis, Mentha spicata) | Leaves | May – August |

| Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) | Berries | September – October |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | Tubers | October – November |

| Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) | Leaves, flowers | June – August |

| Wild Hopniss / Groundnut (Apios americana) | Tubers | September – November |

| Toothwort Root (Cardamine concatenata) | Rhizomes | March – April |

| Devil’s Walking Stick(Aralia spinosa) | Tender young shoots | April – May |

| Wild Prickly Ash (Zanthoxylum americanum) | Berries | August – September |

| Mulberries (Morus rubra) | Ripe berries | May – June |

| Wood Nettles (Laportea canadensis) | Young leaves, tender stems | April – June |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.