Oregon’s forests, beaches, and meadows are full of valuable things you can pick and use. From tasty mushrooms to healing plants, our state offers many natural treasures for people who know where to look. The hunt for these wild goodies connects us to nature and can even put money in your pocket.

Many foragers search for morel mushrooms each spring when they pop up in forests after fires. These wrinkly mushrooms sell for $50 per pound or more to fancy restaurants. Local chefs pay top dollar for fresh, wild foods that you might find growing near your home.

Truffles hide underground in Oregon’s western forests, making them a challenge to find without a trained dog or pig. These rare fungi can bring $400 per pound when sold to food lovers. People travel from all over the world to search for Oregon truffles.

Wild berries grow along trails and forest edges throughout the summer months. Huckleberries and salal berries taste delicious and also make wonderful jams that sell well at farmers markets. Gathering berries gives you time to enjoy beautiful scenery while filling your basket with valuable food.

Medicinal plants like Oregon grape root and elderflowers help people feel better and stay healthy. Herbalists buy these plants to make tinctures, teas, and salves. Learning which plants heal teaches important skills while providing useful items for your family.

What We Cover In This Article:

- What Makes Foreageables Valuable

- Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

- The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

- Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

- When to Forage for Maximum Value

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

What Makes Foreageables Valuable

Some wild plants, mushrooms, and natural ingredients can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re selling them or using them at home, their worth often comes down to a few key things:

The Scarcer the Plant, the Higher the Demand

Some valuable forageables only show up for a short time each year, grow in hard-to-reach areas, or are very difficult to cultivate. That kind of rarity makes them harder to find and more expensive to buy.

Morels, truffles, and ramps are all good examples of this. They’re popular, but limited access and short growing seasons mean people are often willing to pay more.

A good seasonal foods guide can help you keep track of when high-value items appear.

High-End Dishes Boost the Value of Ingredients

Wild ingredients that are hard to find in stores often catch the attention of chefs and home cooks. When something unique adds flavor or flair to a dish, it quickly becomes more valuable.

Truffles, wild leeks, and edible flowers are prized for how they taste and look on a plate. As more people try to include them in special meals, the demand—and the price—tends to rise.

You’ll find many of these among easy-to-identify wild mushrooms or herbs featured in fine dining.

Medicinal and Practical Uses Drive Forageable Prices Up

Plants like ginseng, goldenseal, and elderberries are often used in teas, tinctures, and home remedies. Their value comes from how they support wellness and are used repeatedly over time.

These plants are not just ingredients for cooking. Because people turn to them for ongoing use, the demand stays steady and the price stays high.

The More Work It Takes to Harvest, the More It’s Worth

Forageables that are hard to reach or tricky to harvest often end up being more valuable. Some grow in dense forests, need careful digging, or have to be cleaned and prepared before use.

Matsutake mushrooms are a good example, because they grow in specific forest conditions and are hard to spot under layers of leaf litter. Wild ginger and black walnuts, meanwhile, both require extra steps for cleaning and preparation before they can be used or sold.

All of that takes time, effort, and experience. When something takes real work to gather safely, buyers are usually willing to pay more for it.

Foods That Keep Well Are More Valuable to Buyers

Some forageables, like dried morels or elderberries, can be stored for months without losing their value. These longer-lasting items are easier to sell and often bring in more money over time.

Others, like wild greens or edible flowers, have a short shelf life and need to be used quickly. Many easy-to-identify wild greens and herbs are best when fresh, but can be dried or preserved to extend their usefulness.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

When you’re foraging for high-value plants, mushrooms, or other wild ingredients, every decision matters. Whether you’re selling at a farmers market or stocking your own pantry, simple mistakes can make your harvest less valuable or even completely worthless.

Harvesting at the Wrong Time

Harvesting at the wrong time can turn a valuable find into something no one wants. Plants and mushrooms have a short window when they’re at their best, and missing it means losing quality.

Morels, for example, shrink and dry out quickly once they mature, which lowers their weight and price. Overripe berries bruise in the basket and spoil fast, making them hard to store or sell.

Improper Handling After Harvest

Rough handling can ruin even the most valuable forageables. Crushed mushrooms, wilted greens, and dirty roots lose both their appeal and their price.

Use baskets or mesh bags to keep things from getting smashed and let air circulate. Keeping everything cool and clean helps your harvest stay fresh and look better for longer.

This is especially important for delicate items like wild roots and tubers that need to stay clean and intact.

Skipping Processing Steps

Skipping basic processing steps can cost you money. A raw harvest may look messy, spoil faster, or be harder to use.

For example, chaga is much more valuable when dried and cut properly. Herbs like wild mint or nettle often sell better when bundled neatly or partially dried. If you skip these steps, you may end up with something that looks unappealing or spoils quickly.

Collecting from the Wrong Area

Harvesting in the wrong place can ruin a good find. Plants and mushrooms pulled from roadsides or polluted ground may be unsafe, no matter how fresh they look.

Buyers want to know their food comes from clean, responsible sources. If a spot is known for overharvesting or damage, it can make the whole batch less appealing.

These suburbia foraging tips can help you find overlooked spots that are surprisingly safe and productive.

Not Knowing the Market

A rare plant isn’t valuable if nobody wants to buy it. If you gather in-demand species like wild ramps or black trumpets, you’re more likely to make a profit. Pay attention to what chefs, herbalists, or vendors are actually looking for.

Foraging with no plan leads to wasted effort and unsold stock. Keeping up with demand helps you bring home a profit instead of a pile of leftovers.

You can also brush up on foraging for survival strategies to identify the most versatile and useful wild foods.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

Some of the most sought-after wild plants and fungi here can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re foraging for profit or personal use, these are the ones worth paying attention to:

Matsutake Mushroom (Tricholoma matsutake)

Matsutake mushrooms grow under pine trees, working together with the tree roots. They have firm white flesh and smell like a mix of cinnamon and pine. The caps start round and then flatten out, growing 2-8 inches wide with brown scales.

You can spot these mushrooms by their thick stem, the ring around them, and their strong, spicy smell. Watch out for the toxic Amanita mushrooms that look similar but don’t have the same smell.

You can eat both the caps and stems. People love to use matsutake in soups and rice dishes. In Japan, these mushrooms are special and mean good luck.

Matsutake mushrooms are rare and hard to find. Their habitats are shrinking. Some perfect ones can sell for over $100 each in special markets, making them some of the most valuable wild mushrooms you can find.

Oregon White Truffle (Tuber oregonense)

Hidden beneath the forest floor, Oregon White Truffles create a network of tiny threads among Douglas fir roots. These potato-shaped treasures range from marble to golf ball size with a marbled interior that changes from white to beige as they ripen.

The entire truffle is edible and can be shaved raw over foods or mixed into oils and butter. Their complex smell blends garlic, cheese, and earthy notes that make food taste amazing.

To tell it’s real, check the marbled pattern inside. Fake truffles don’t smell as good and look different inside. Many collectors use trained dogs to find real truffles without hurting the forest.

Chefs will pay $200-$400 for just one pound of fresh Oregon White Truffles. Their short season and the skill needed to find them without damaging their growing spots makes them truly special.

Huckleberry (Vaccinium spp.)

Huckleberries grow on woody shrubs and bear dark berries that range from blue to nearly purple-black, often with a slightly gritty skin. The flavor is strong—sweet, tangy, and sometimes almost wild-tasting, especially when fresh.

You’ll usually find them cooked into sauces, made into compotes, or baked into muffins and pancakes. The leaves and stems aren’t edible, so only the fruit should be harvested.

While they’re similar in color to blueberries, huckleberries have larger seeds and a more robust flavor. Some people confuse them with deadly nightshade, but nightshade berries are glossier and grow in hanging clusters, not singly.

If you chew a huckleberry, expect a bit of crunch from the seeds, which helps set them apart from softer, smoother berries.

Sea Bean (Salicornia pacifica)

Sea beans grow in salty marshes where most plants can’t survive. They don’t have normal leaves. Instead, they have bright green jointed stems that grow up to about 12 inches tall. When you bite them, they’re crunchy and naturally salty.

You can eat all the parts that grow above ground. Try them raw in salads or lightly cooked as a side dish. They’re already salty, so you don’t need to add much salt when cooking them.

When picking sea beans, cut the top parts rather than pulling up the whole plant. This lets them grow back. There are some plants that look similar in marshes, but most aren’t harmful.

Restaurants pay good money for sea beans because they add unique crunch and natural saltiness to dishes. They also contain vitamin C and minerals from the sea, making them good for you as well as tasty.

Camas Bulb (Camassia quamash)

Star-shaped blue-purple flowers signal the presence of camas, a plant deeply connected to Native American history. For thousands of years, tribes across western North America relied on camas bulbs as a staple food and valuable trading item.

Only proper cooking makes the bulb safe and tasty. Raw bulbs contain inulin that humans can’t digest, but slow cooking transforms them into sweet, pear-flavored treats. Traditional methods involved pit cooking for 1-3 days, though modern cooks use ovens instead.

Correct identification saves lives. Death camas looks similar but is deadly poisonous. True camas has blue-purple flowers, while death camas produces white or cream blooms.

The cultural importance of camas continues today. When collecting, remember it’s still sacred to many Native American communities. Always leave plenty to grow back. The unique sweet flavor that develops after cooking and its rich history make camas a truly special find.

Blackcap Raspberry (Rubus leucodermis)

The blackcap raspberry grows as a thorny shrub reaching 3-6 feet tall with distinctive bluish-white stems that appear almost powdery. Its berries transform from green to red and finally to a deep purple-black when fully ripe, offering a sweet-tart flavor with subtle floral notes.

These wild berries grow in clusters and can be found along forest edges, disturbed areas, and old logging roads throughout western North America. Unlike the more common red raspberry, blackcaps have a deeper, more complex flavor that many foragers prefer.

The entire berry is edible, with no parts to remove. Look for the characteristic hollow core when you pick them – this helps distinguish them from other similar berries. They can be eaten fresh, added to desserts, or made into jams and syrups.

Blackcaps contain high levels of antioxidants and vitamin C, making them not just delicious but nutritious too. Their limited commercial availability makes them especially prized by wild food enthusiasts.

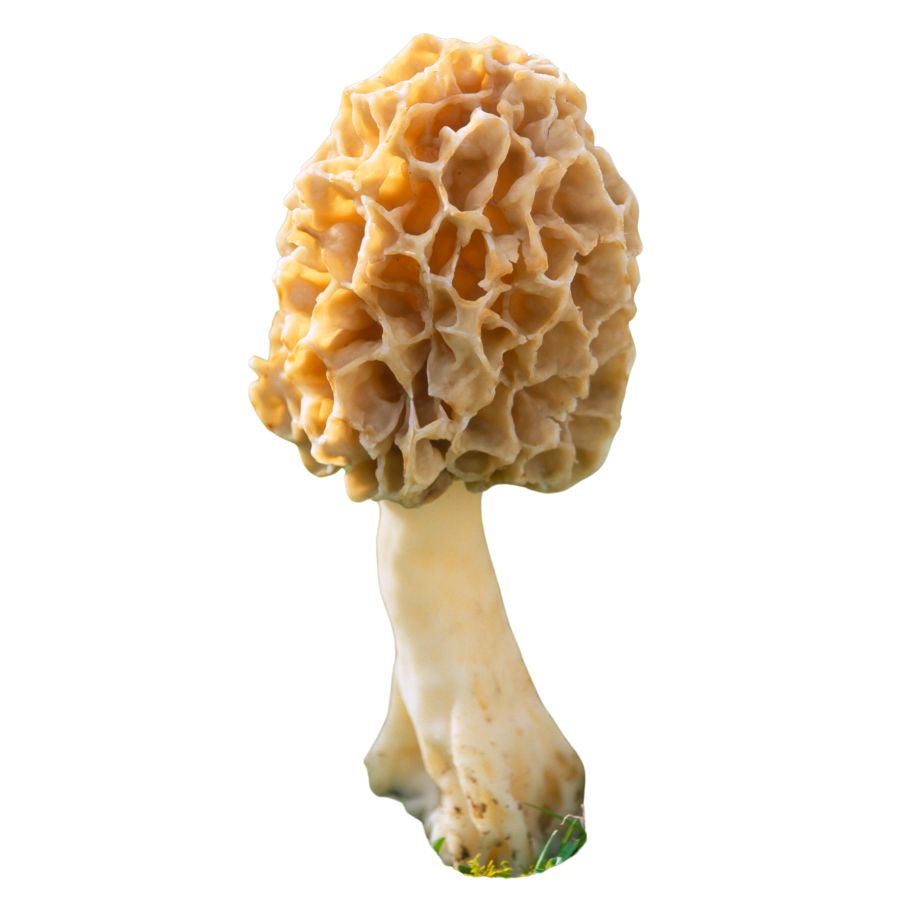

Morel Mushroom (Morchella spp.)

With their distinctive honeycomb-patterned caps and hollow stems, morel mushrooms are among the most sought-after wild fungi in North America. These mushrooms feature a nutty, earthy flavor that intensifies when cooked, making them prized ingredients in gourmet cooking.

Identifying morels correctly is crucial, as they have toxic lookalikes. True morels are completely hollow inside when cut lengthwise, including the stem. False morels (Gyromitra spp.) have a brain-like cap and cotton-like material inside the stem.

Morels typically grow in forest areas, especially around dying elms, old apple orchards, and recently burned areas. They have a symbiotic relationship with certain trees and appear in spring when soil temperatures reach the right level.

Always cook morels thoroughly before eating, as they contain small amounts of toxins that are destroyed by heat. Their umami-rich flavor makes them valuable in risottos, pasta dishes, and sauces. Their limited seasonal availability and difficulty to cultivate commercially adds to their value.

Wild Watercress (Nasturtium officinale)

Watercress, also known as yellowcress or garden cress, is an aquatic plant with small, rounded green leaves and hollow stems that often float along the water’s surface. It usually grows in dense mats, and the bright green color is one of the easiest ways to spot it in clear, shallow streams and ponds.

Besides being a popular edible green, watercress has been traditionally used in herbal remedies, especially for boosting digestion and respiratory health.

The leaves and stems are edible, offering a crisp texture and a peppery, slightly spicy taste that can remind you of arugula. People often enjoy it raw in salads, blended into soups, or lightly wilted into stir-fries for a fresh bite.

Stick to eating the leaves and stems, and avoid any parts that look yellowed or slimy, since healthy watercress should always look vibrant and clean.

Watercress has a few lookalikes, like lesser celandine or young wild mustard, but true watercress has a distinct, sharp flavor and tends to grow only in moving, clean water. Always double-check your identification, because gathering from stagnant or contaminated water sources can expose you to harmful bacteria or parasites.

Fiddlehead Fern (Athyrium filix-femina)

Tightly coiled and resembling the scroll on a violin, fiddleheads are the young unfurled fronds of the lady fern. These vibrant green spirals emerge from the forest floor in clusters and offer a unique flavor often described as a blend between asparagus and green beans with nutty undertones.

The ideal harvest time is when fiddleheads are still tightly coiled and about 1-3 inches tall. Only harvest a few fronds from each plant to ensure its continued growth. The lady fern variety is generally considered safe when properly prepared.

Not all ferns produce edible fiddleheads. Avoid bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum), which contains carcinogens. Lady fern fiddleheads have a U-shaped groove on the inside of the stem and papery brown scales.

Proper preparation involves removing all brown papery material and boiling for at least 10 minutes or steaming for 20 minutes before sautéing. This traditional food of many indigenous peoples pairs wonderfully with butter, garlic, and a squeeze of lemon.

Wild Hazelnut (Corylus cornuta var. californica)

Native to the western United States, wild hazelnuts grow on multi-stemmed shrubs that reach 6-12 feet tall with heart-shaped, serrated leaves. Unlike their commercial counterparts, these wild nuts are smaller but pack an intensely rich, sweet flavor that many find superior to store-bought varieties.

The nuts develop inside distinctive husks with long, beak-like extensions that give them their other common name, “beaked hazelnut.” These husks turn from green to brown as the nuts ripen in late summer to early fall.

Harvesting requires careful timing – too early and the nuts aren’t developed, too late and wildlife will have claimed them. The entire nut is edible once removed from its husk and hard shell. Some foragers roast them to enhance their buttery flavor.

Wild hazelnuts are nutritional powerhouses containing healthy fats, protein, fiber, vitamins, and minerals. Their concentrated caloric value made them an important food source for many Native American tribes. They can be eaten raw, roasted, or ground into flour for baking.

Blue Elderberry (Sambucus cerulea)

Blue elderberry trees stand out with their clusters of tiny creamy-white flowers that transform into dusty blue-purple berries by late summer. These berries appear powdery because of their natural waxy coating that helps preserve their freshness.

The berries grow in flat-topped or slightly rounded clusters that can be quite heavy when ripe. Only the fully ripened berries should be gathered, as unripe berries contain higher levels of compounds that can cause stomach upset.

While the berries are edible when cooked, the stems, leaves, roots, and seeds contain cyanide-producing compounds and should be avoided. Always remove berries from stems before processing them. The flowers are also edible and make wonderful syrups and teas.

Elderberries have been used medicinally for centuries to boost immune function and fight colds. They’re rich in vitamin C and antioxidants. The berries make excellent jellies, syrups, and wines, but are rarely eaten raw due to their tartness. Their beautiful purple juice is also used as a natural food coloring.

King Bolete (Boletus edulis)

King Bolete is a prized mushroom with a brown cap and thick stem. The cap can grow up to 10 inches wide, ranging from light tan to dark brown. When cooked, its white flesh stays firm and has a rich, nutty taste that gets stronger when dried.

To find this mushroom, look for a spongy bottom surface instead of gills. The stem is thick at the base with a net-like pattern. King Boletes never have a ring on the stem.

Be careful not to pick the bitter bolete, which looks similar but tastes awful. Cut mushrooms and check if they turn blue – real King Boletes stay the same color when cut.

You can eat the whole mushroom. Many people dry slices to make the flavor stronger or cook them fresh in butter. They contain good protein and vitamin D, making them healthy and tasty.

Wild Ginger (Asarum caudatum)

Wild Ginger grows as a carpet of heart-shaped leaves on forest floors in the Pacific Northwest. These plants spread underground and create thick ground cover under tall trees. When crushed, the leaves smell like spicy ginger.

The plant makes brownish-purple flowers close to the ground, often hidden under leaves. These small flowers attract insects for pollination.

People mainly use the underground stems, which have a strong, earthy flavor more powerful than store-bought ginger.

Don’t mix it up with European ginger types. The Pacific kind has shinier, rounder leaves with clear heart shapes.

Native peoples used Wild Ginger for colds, stomach problems, and adding flavor to foods. Today, people collect it for its smell and to make teas and preserves. Always take just a little so the plants can grow back.

Pacific Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus formosus)

Pacific Golden Chanterelles look like golden-orange trumpets growing from the forest floor after fall rains. Instead of flat gills, they have ridge-like folds running down their stems. They smell fruity, like apricots, and taste slightly peppery.

You can eat the whole mushroom. Clean them with a brush instead of water because they soak up moisture fast.

Watch out for fake chanterelles, which have true gills and no fruity smell. Also avoid Jack-o-lantern mushrooms, which grow on wood and glow in the dark.

These mushrooms grow with tree roots in a way that helps both survive. This special relationship means people can’t grow them on farms.

Cooks love chanterelles because they stay firm when cooked. They contain vitamins B and D, copper, and potassium. Cooking them slowly brings out their best flavor.

Wild Rose Hip (Rosa nutkana)

After the pink flowers of Nootka Rose fade, bright red rose hips grow on their thorny stems. These small, round fruits hold the plant’s seeds inside sweet-tart flesh. Each hip grows about as big as a marble and turns red in late summer.

The outer part contains more vitamin C than oranges. Inside are tiny hairs around the seeds that you must remove before eating because they can upset your stomach.

You can spot wild rose hips by their round shape and the dried flower parts at the tip. They grow on thorny plants with compound leaves, unlike similar-looking hawthorn berries.

People use rose hips to make teas, jams, and syrups. They help support the immune system.

Rose hips fight inflammation with their high levels of antioxidants. They naturally thicken jams without adding extra ingredients. When picking, choose firm hips that give slightly when squeezed.

Wild Gooseberry (Ribes divaricatum)

Wild Gooseberry bushes protect their fruits with sharp thorns. These plants grow small, round berries that hang alone or in small groups on branches. Ripe berries are dark purple and taste both sweet and tangy.

The bushes can grow up to six feet tall and lose their leaves in winter. Their lobed leaves look like those of currants, which are related plants.

You can eat the whole berry raw or cooked. They work great in jams, pies, and homemade wines.

Look for thorns at the stem joints and berries with visible lines or stripes. Unlike gooseberries, currants have no thorns and grow in longer clusters.

Native Americans mixed these berries with other foods to add flavor. Sailors ate them to prevent scurvy because of their high vitamin C. Today, people pick Wild Gooseberries for their special taste that store-bought ones can’t match. The berries also provide good antioxidants and fiber.

Cattail (Typha latifolia)

Cattails, often called bulrushes or corn dog grass, are easy to spot with their tall green stalks and brown, sausage-shaped flower heads. They grow thickly along the edges of ponds, lakes, and marshes, forming dense stands that are hard to miss.

Almost every part of the cattail is edible, including the young shoots, flower heads, and starchy rhizomes. You can eat the tender shoots raw, boil the flower heads like corn on the cob, or grind the rhizomes into flour for baking.

Besides food, cattails have long been used for making mats, baskets, and even insulation by weaving the dried leaves and using the fluffy seeds. Their combination of usefulness and abundance has made them an important survival plant for many cultures.

One thing you need to watch for is young cattail shoots being confused with similar-looking plants like iris, which are toxic. A real cattail shoot will have a mild cucumber-like smell when you snap it open, while iris plants smell bitter or unpleasant.

Manzanita Berry (Arctostaphylos spp.)

Manzanita berries dangle like tiny apples from shrubs with striking red-brown bark that peels in thin layers. These small, round fruits start green, then ripen to a bright red or reddish-brown color. The berries have a mealy texture and taste both sweet and tart with a slight astringency that many compare to crab apples.

The plant’s name comes from Spanish, meaning “little apple,” which perfectly describes the appearance of these small fruits. Manzanita shrubs stand out with their twisted branches and smooth bark.

You can eat the berries raw, though many people prefer to make them into jelly, cider, or dry them for later use. The seeds inside are hard and should not be chewed.

To identify manzanita, look for evergreen leaves that are thick, leathery, and oval-shaped. Don’t confuse them with madrone trees, which have similar bark but larger leaves and bigger berries.

Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

Some parts of the state are better than others when it comes to finding valuable wild plants and mushrooms. Here are the different places where you’re most likely to have luck:

| Plants | Specific Locations |

|---|---|

| Matsutake Mushroom (Tricholoma matsutake) | – Tillamook State Forest – Umpqua National Forest buffer zone (east side) – Elliott State Forest |

| Oregon White Truffle (Tuber oregonense) | – Coast Range near Philomath – Marys Peak area – McDonald-Dunn Forest |

| Wild Huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum) | – Mt. Hebo area – Ochoco Mountains (Lookout Mountain region) – Calapooya Mountains |

| Sea Bean (Salicornia pacifica) | – Netarts Bay mudflats – Yaquina Bay estuary – South Slough National Estuarine Reserve |

| Camas Bulb (Camassia quamash) | – Baskett Slough region – French Prairie wet meadows – Wapato Lake area |

| Blackcap Raspberry (Rubus leucodermis) | – Eola Hills – Siskiyou foothills – Banks-Vernonia State Trail edges |

| Morel Mushroom (Morchella spp.) | – Burn zones near Glide – Strawberry Mountain foothills – Warner Mountains (southern edge) |

| Wild Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | – Silver Creek near Silverton – Butte Creek (near Scotts Mills) – Alsea River headwaters |

| Fiddlehead Fern (Athyrium filix-femina) | – Nestuca River corridor – North Santiam River valley – Drift Creek wilderness buffer |

| Wild Hazelnut (Corylus cornuta var. californica) | – Molalla River State Scenic Corridor – Luckiamute State Natural Area – Applegate Valley edges |

| Blue Elderberry (Sambucus cerulea) | – Rogue River banks – John Day Valley (Dayville outskirts) – Yamhill River trail zones |

| King Bolete (Boletus edulis) | – Siuslaw forest buffer near Mapleton – Rogue-Umpqua Divide area – Laurel Hill near Welches |

| Wild Ginger (Asarum caudatum) | – Columbia Gorge slopes near Bridal Veil – Peavy Arboretum woodlands – Upper Nestucca drainage |

| Pacific Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus formosus) | – Tillamook Burn region – Mount Hood State Forest – McKenzie River trail zone |

| Wild Rose Hip (Rosa nutkana) | – West Eugene wetlands – Metolius River trail region – Applegate Lake trail surroundings |

| Wild Gooseberry (Ribes divaricatum) | – Detroit Lake region – Illinois River canyon – North Powder valley hedgerows |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | – Ankeny National Wildlife Refuge (non-federal zone) – Fern Ridge Reservoir marshes – Bandon marsh edge zone |

| Manzanita Berry (Arctostaphylos spp.) | – South Ashland hills – Cascade-Siskiyou foothills – Dead Indian Memorial Road region |

When to Forage for Maximum Value

Every valuable wild plant or mushroom has its season. Here’s a look at the best times for harvest:

| Plants | Valuable Parts | Best Harvest Season |

|---|---|---|

| Matsutake Mushroom (Tricholoma matsutake) | Mature fruiting bodies | September – November |

| Oregon White Truffle (Tuber oregonense) | Underground truffle body | December – March |

| Wild Huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum) | Ripe berries | July – September |

| Sea Bean (Salicornia pacifica) | Young green shoots | May – July |

| Camas Bulb (Camassia quamash) | Cooked bulbs | May – June (bulbs after flowering) |

| Blackcap Raspberry (Rubus leucodermis) | Ripe berries | June – July |

| Morel Mushroom (Morchella spp.) | Fruiting bodies | April – June |

| Wild Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | Tender leaves and stems | March – May, September – October |

| Fiddlehead Fern (Athyrium filix-femina) | Young unfurled fronds | March – April |

| Wild Hazelnut (Corylus cornuta var. californica) | Mature nuts | September – October |

| Blue Elderberry (Sambucus cerulea) | Ripe berries | August – September |

| King Bolete (Boletus edulis) | Fruiting bodies | September – October |

| Wild Ginger (Asarum caudatum) | Aromatic rhizomes | April – June |

| Pacific Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus formosus) | Fruiting bodies | September – December |

| Wild Rose Hip (Rosa nutkana) | Ripe rose hips | October – November |

| Wild Gooseberry (Ribes divaricatum) | Ripe berries | May – June |

| Cattail Shoot (Typha latifolia) | Inner young shoots | April – May |

| Manzanita Berry (Arctostaphylos spp.) | Ripe berries | August – September |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.