New Jersey offers so many amazing plants you can gather for free. The state has beaches, forests, and meadows where edible and useful plants grow wild. You just need to know where to look and what’s safe to collect.

Foraging connects you to nature in a way few other activities can. When you pick your own berries or mushrooms, you experience the land as our ancestors did. It also saves money while providing fresh, healthy foods.

The best part about foraging in New Jersey is the variety across different regions. The Pine Barrens contain unique plants you won’t find in the northern highlands. Coastal areas offer salty treats that inland spots don’t have.

Wild foods in New Jersey are both tasty and good for you. Many contain vitamins and minerals that store-bought foods lack. Knowing which plants to gather makes your outdoor adventures even more rewarding.

What We Cover In This Article:

- What Makes Foreageables Valuable

- Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

- The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

- Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

- When to Forage for Maximum Value

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

What Makes Foreageables Valuable

Some wild plants, mushrooms, and natural ingredients can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re selling them or using them at home, their worth often comes down to a few key things:

The Scarcer the Plant, the Higher the Demand

Some valuable forageables only show up for a short time each year, grow in hard-to-reach areas, or are very difficult to cultivate. That kind of rarity makes them harder to find and more expensive to buy.

Morels, truffles, and ramps are all good examples of this. They’re popular, but limited access and short growing seasons mean people are often willing to pay more.

A good seasonal foods guide can help you keep track of when high-value items appear.

High-End Dishes Boost the Value of Ingredients

Wild ingredients that are hard to find in stores often catch the attention of chefs and home cooks. When something unique adds flavor or flair to a dish, it quickly becomes more valuable.

Truffles, wild leeks, and edible flowers are prized for how they taste and look on a plate. As more people try to include them in special meals, the demand—and the price—tends to rise.

You’ll find many of these among easy-to-identify wild mushrooms or herbs featured in fine dining.

Medicinal and Practical Uses Drive Forageable Prices Up

Plants like ginseng, goldenseal, and elderberries are often used in teas, tinctures, and home remedies. Their value comes from how they support wellness and are used repeatedly over time.

These plants are not just ingredients for cooking. Because people turn to them for ongoing use, the demand stays steady and the price stays high.

The More Work It Takes to Harvest, the More It’s Worth

Forageables that are hard to reach or tricky to harvest often end up being more valuable. Some grow in dense forests, need careful digging, or have to be cleaned and prepared before use.

Matsutake mushrooms are a good example, because they grow in specific forest conditions and are hard to spot under layers of leaf litter. Wild ginger and black walnuts, meanwhile, both require extra steps for cleaning and preparation before they can be used or sold.

All of that takes time, effort, and experience. When something takes real work to gather safely, buyers are usually willing to pay more for it.

Foods That Keep Well Are More Valuable to Buyers

Some forageables, like dried morels or elderberries, can be stored for months without losing their value. These longer-lasting items are easier to sell and often bring in more money over time.

Others, like wild greens or edible flowers, have a short shelf life and need to be used quickly. Many easy-to-identify wild greens and herbs are best when fresh, but can be dried or preserved to extend their usefulness.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

When you’re foraging for high-value plants, mushrooms, or other wild ingredients, every decision matters. Whether you’re selling at a farmers market or stocking your own pantry, simple mistakes can make your harvest less valuable or even completely worthless.

Harvesting at the Wrong Time

Harvesting at the wrong time can turn a valuable find into something no one wants. Plants and mushrooms have a short window when they’re at their best, and missing it means losing quality.

Morels, for example, shrink and dry out quickly once they mature, which lowers their weight and price. Overripe berries bruise in the basket and spoil fast, making them hard to store or sell.

Improper Handling After Harvest

Rough handling can ruin even the most valuable forageables. Crushed mushrooms, wilted greens, and dirty roots lose both their appeal and their price.

Use baskets or mesh bags to keep things from getting smashed and let air circulate. Keeping everything cool and clean helps your harvest stay fresh and look better for longer.

This is especially important for delicate items like wild roots and tubers that need to stay clean and intact.

Skipping Processing Steps

Skipping basic processing steps can cost you money. A raw harvest may look messy, spoil faster, or be harder to use.

For example, chaga is much more valuable when dried and cut properly. Herbs like wild mint or nettle often sell better when bundled neatly or partially dried. If you skip these steps, you may end up with something that looks unappealing or spoils quickly.

Collecting from the Wrong Area

Harvesting in the wrong place can ruin a good find. Plants and mushrooms pulled from roadsides or polluted ground may be unsafe, no matter how fresh they look.

Buyers want to know their food comes from clean, responsible sources. If a spot is known for overharvesting or damage, it can make the whole batch less appealing.

These suburbia foraging tips can help you find overlooked spots that are surprisingly safe and productive.

Not Knowing the Market

A rare plant isn’t valuable if nobody wants to buy it. If you gather in-demand species like wild ramps or black trumpets, you’re more likely to make a profit. Pay attention to what chefs, herbalists, or vendors are actually looking for.

Foraging with no plan leads to wasted effort and unsold stock. Keeping up with demand helps you bring home a profit instead of a pile of leftovers.

You can also brush up on foraging for survival strategies to identify the most versatile and useful wild foods.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

Some of the most sought-after wild plants and fungi here can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re foraging for profit or personal use, these are the ones worth paying attention to:

Black Walnut (Juglans nigra)

Black walnuts reveal themselves through deeply furrowed bark and compound leaves arranged along branches. When ripe, their green husks turn yellowish-brown and fall naturally, staining hands with their dark pigment.

The nuts hide inside extremely hard shells that require serious tools to crack. Their distinctive flavor, earthy, sweet, and tangy, outshines store-bought walnuts in complexity and depth.

Black walnuts command premium prices at farmers’ markets for their culinary versatility. They shine in baked goods, ice cream, and savory dishes alike.

Once properly dried, these nuts store exceptionally well, providing nutrient-dense wild food throughout the year. Their high oil content delivers healthy omega-3 fatty acids and rich, satisfying flavor.

Hen of the Woods (Grifola frondosa)

The meaty texture and rich umami flavor make Hen of the Woods a prize for foragers and chefs alike. This mushroom grows in overlapping clusters resembling ruffled chicken feathers at the base of oak trees.

Look for grayish-brown to tan caps with white pore surfaces underneath. A single cluster can weigh up to 50 pounds, offering an impressive harvest from just one find.

When cooking, the firm texture holds up beautifully while absorbing surrounding flavors. Everything except the tough base can be eaten after proper preparation.

Few dangerous lookalikes exist, making this an approachable mushroom for newer foragers. Its immune-boosting properties and potential anti-cancer compounds add to its value beyond the kitchen.

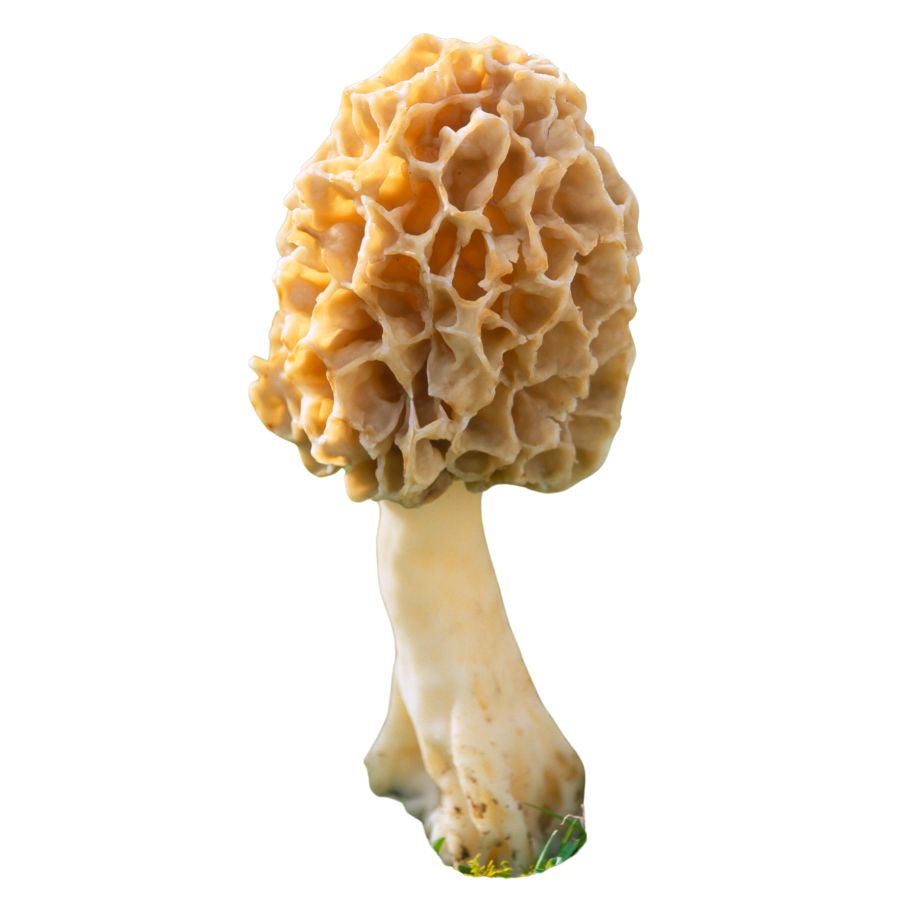

Morel Mushroom (Morchella spp.)

The distinctive honeycomb pattern covering morel mushroom caps makes them unmistakable forest treasures. These hollow fungi emerge with conical, pitted caps attached directly to their stems.

Always cut morels lengthwise to confirm they’re completely hollow, a key identification feature. False morels have caps hanging free from the stem and aren’t hollow inside, an important distinction since false morels are toxic.

Their nutty, earthy flavor develops a wonderful meaty quality when sautéed in butter. Never eat morels raw, as they contain compounds that require heat treatment to make them safe.

The impossibility of commercial cultivation makes wild morels extraordinarily valuable. Chefs eagerly pay premium prices for these fleeting delicacies each spring.

Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

Crush a leaf between your fingers and you’ll immediately understand why this plant is named garlic mustard. The distinct aroma gives away its identity while offering a preview of its flavor potential.

First-year plants form ground-level rosettes with kidney-shaped leaves. In the second year, they shoot up stalks with triangular leaves and small white four-petaled flowers.

No poisonous lookalikes exist, making garlic mustard ideal for beginning foragers. The entire plant, leaves, flowers, seeds, and roots, is edible, though young leaves offer the mildest flavor.

As an invasive species, harvesting garlic mustard actually benefits native ecosystems. The leaves make excellent pesto, add punch to salads, and can be cooked like spinach.

Wild Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

The intoxicating aroma falling somewhere between garlic and onion signals you’ve found wild ramps. These woodland treasures grow in tight clusters with broad, smooth leaves sprouting from white bulbs partially buried in rich soil.

To distinguish from potentially toxic lily-of-the-valley, look for flat (not folded) leaves and the unmistakable onion smell when torn. True ramps always emit that signature allium scent.

Both the leaves and bulbs are edible, with the leaves offering milder flavor and the bulbs delivering more punch. Their unique taste has made them a sought-after ingredient in high-end restaurants.

Sustainable harvesting is critical with ramps due to their slow growth rate and specific habitat requirements. The limited season and growing concerns about overharvesting have driven up their market value considerably.

Wineberry (Rubus phoenicolasius)

Wineberry canes stand out with their reddish-purple stems covered in distinctive red bristles that catch the light beautifully. The berries emerge from fuzzy calyxes, ripening from white to red to a deep wine color that gives them their name.

Unlike cultivated raspberries, wineberries have a perfect balance of sweetness and acidity with complex wine-like undertones. Their hollow core makes them easy to distinguish from blackberries, which have solid centers.

The berries are the edible prize, ready to harvest when they pull away easily from the stem. No toxic lookalikes exist, though the canes have thorns that require careful handling.

Wineberries rarely appear in markets because they don’t ship well, making them a treasured wild food. They’re packed with antioxidants and vitamin C while offering unique flavor profiles impossible to find in commercial berries.

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba)

Pawpaw trees produce North America’s largest native fruit with custard-like flesh tasting of banana, mango, and vanilla all at once. These understory trees have long, tropical-looking leaves and grow in patches or groves near water.

The fruit resembles small green mangoes that turn yellowish-brown when ripe and feel soft to the touch. Cut one open to reveal creamy yellow flesh and large dark seeds arranged in a row.

No poisonous lookalikes exist, though unripe pawpaws can cause stomach upset. Only the custard-like flesh is edible; discard the seeds and skin.

Their tropical flavor profile is entirely unexpected in the Northeast, yet they’re nearly impossible to find commercially. The fruits bruise easily and have an extremely short shelf life, making them a true forager’s prize.

Chanterelle Mushroom (Cantharellus spp.)

Chanterelles glow like golden trumpets on the forest floor, with their funnel-shaped caps and blunt, wavy edges. These mushrooms aren’t truly gilled; instead, they have ridge-like folds that run down the stem.

Their apricot-like fragrance and golden-yellow to orange color make chanterelles easily recognizable. When cut, they reveal white flesh that never changes color.

Beware of the toxic false chanterelle, which has true gills instead of ridges and lacks the fruity aroma. Jack-o-lantern mushrooms also look similar but grow on wood rather than soil.

The entire mushroom is edible and prized for its delicate, fruity flavor with peppery undertones. Their inability to be commercially cultivated keeps chanterelles valuable and sought-after by restaurants for their unique flavor profile and visual appeal.

Wild Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

Wild blueberries grow on low-lying bushes with small, oval leaves and bell-shaped white or pink flowers. The berries themselves are smaller than cultivated varieties but pack an intensely concentrated flavor that store-bought berries can’t match.

Look for clusters of dusty blue berries on knee-high shrubs growing in acidic soil. The telltale “crown” on the end of each berry helps identify them as true blueberries.

While no dangerous lookalikes exist in New Jersey, blue cohosh berries might confuse beginners but lack the crown and grow on much taller plants. The entire berry is edible and needs no special preparation.

What makes wild blueberries special is their significantly higher antioxidant content compared to cultivated varieties. Their small size means more skin per volume, where most of the beneficial compounds hide.

American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)

American persimmons transform from astringent, mouth-puckering fruits to honey-sweet treasures after the first frost softens their flesh. The small trees produce round, orange-brown fruits with a distinctive four-part calyx “cap” at the top.

Mature fruits range from 1-2 inches in diameter and develop deep wrinkles when fully ripe. Patience is crucial when harvesting; unripe persimmons contain high levels of tannins that create an unforgettable astringent sensation.

There are no toxic lookalikes, though Asian persimmon varieties appear similar but are larger and can be eaten while still firm. Only fully ripened fruits should be collected, ideally those that have fallen naturally from the tree.

The sweet, date-like flesh can be eaten fresh or processed into puddings, breads, and preserves. Some foragers dry the fruits like dates for long-term storage.

Spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

Spicebush grows as an understory shrub in moist woodlands, offering a citrusy, spicy fragrance when any part is crushed. The plant features bright yellow early spring flowers and glossy red berries in fall.

Simply snap a twig or crush a leaf to release the unmistakable scent reminiscent of allspice. This aromatic quality makes identification straightforward for beginners.

Both berries and twigs can be harvested for culinary use. The berries, found only on female plants, can be dried and ground as a spice similar to allspice.

Native Americans used spicebush medicinally for centuries. Today, its unique flavor profile makes it sought after by foragers and chefs looking to create truly local dishes with flavors impossible to find in grocery stores.

Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica)

The young shoots of Japanese knotweed taste surprisingly like rhubarb with hints of green apple. These reddish, hollow stems emerge in spring and can grow several inches per day.

Look for distinctive zigzag stem patterns and red-speckled stalks that quickly reach heights of 10 feet. The plant forms dense stands with large, heart-shaped leaves and small white flower clusters by summer.

Only harvest the young shoots when they’re under 8 inches tall for the best flavor and texture. Once collected, prepare them like rhubarb in pies, jams, or savory dishes.

Despite being an aggressive invasive species, knotweed contains high levels of resveratrol, the same heart-healthy compound found in red wine. Eating it helps control its spread while providing a free, nutritious wild vegetable.

Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica)

The tiny hollow hairs covering nettle stems and leaves inject irritating compounds when touched, creating the famous sting. Wear gloves when harvesting this incredibly nutritious plant, which grows upright with opposite, toothed leaves.

Once properly cooked, the stinging compounds disappear completely. The plant transforms into a delicious green with a richer, more complex flavor than spinach.

The young leaves and stems make excellent soups, pasta fillings, and tea. Many foragers dry the leaves for year-round use in medicinal teas.

Its exceptional nutritional profile exceeds most cultivated greens, containing up to 40% protein by dry weight. Herbalists have long used nettle to treat allergies, inflammation, and anemia, making it worth braving its temporary sting.

Beach Plum (Prunus maritima)

The intense sweet-tart flavor of beach plums comes from their harsh growing conditions along sandy coastal areas. These native shrubs produce small, round fruits ranging from purple-blue to crimson when ripe.

The plants reach about 6 feet tall with oval, finely toothed leaves. By late summer, the marble-sized fruits develop a waxy bloom similar to cultivated plums.

Beach plum jam has achieved almost legendary status among coastal communities. The fruits contain high pectin, creating perfect preserves with minimal added ingredients.

Their limited growing range along the Atlantic coast makes these fruits particularly precious. Many New Jersey families have secret beach plum harvesting spots passed down through generations, highlighting their cultural significance beyond mere food value.

Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album)

A powdery white coating covers the diamond-shaped leaves of lamb’s quarters, making them look like someone dusted them with flour. This common “weed” grows in disturbed soil throughout New Jersey.

Young plants have a branching pattern with leaves that alternate along the stems. The white mealy coating on the underside of leaves helps distinguish it from potential lookalikes.

The tender leaves and shoots taste mild with earthy notes and a hint of mineral richness. They can replace spinach in any recipe, whether raw in salads or cooked in soups and stir-fries.

This overlooked plant contains three times more calcium than spinach and significant amounts of vitamins A and C. Its widespread availability in urban environments makes it one of the most accessible wild foods for beginning foragers.

Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

Some parts of the state are better than others when it comes to finding valuable wild plants and mushrooms. Here are the different places where you’re most likely to have luck:

| Plant | Locations |

|---|---|

| Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | – Hacklebarney State Park – Cheesequake State Park – Thompson Park (Monmouth County) |

| Hen of the Woods (Grifola frondosa) | – Wharton State Forest – Allaire State Park – Parvin State Park |

| Morel Mushroom (Morchella spp.) | – Sourland Mountain Preserve – Voorhees State Park – Musconetcong River floodplain trails |

| Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | – South Mountain Reservation – Washington Crossing State Park – Belleplain State Forest |

| Wild Ramps (Allium tricoccum) | – High Point State Park – Jenny Jump State Forest – Stephens State Park |

| Wineberry (Rubus phoenicolasius) | – Hartshorne Woods Park – Sourland Mountain Preserve – Ramapo Valley County Reservation |

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | – Duke Island Park – Rancocas State Park – Voorhees State Park |

| Chanterelle Mushroom (Cantharellus spp.) | – Stokes State Forest – Wawayanda State Park – Double Trouble State Park |

| Wild Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) | – Brendan T. Byrne State Forest – Bass River State Forest – Franklin Parker Preserve |

| American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | – Belleplain State Forest – Crosswicks Creek Park – Estell Manor Park |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | – Watchung Reservation – Rancocas Nature Center – Kittatinny Valley State Park |

| Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) | – Rahway River Parkway – Glenhurst Meadows – Cooper River Park |

| Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) | – Black River County Park – Wawayanda State Park – Holmdel Park |

| Beach Plum (Prunus maritima) | – Island Beach State Park – Sandy Hook Unit – Corson’s Inlet State Park |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | – Johnson Park (Piscataway) – Estell Manor Park – Riverfront Park (Newark) |

When to Forage for Maximum Value

Every valuable wild plant or mushroom has its season. Here’s a look at the best times for harvest:

| Plants | Valuable Parts | Best Harvest Season |

|---|---|---|

| Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | Nuts | September – October |

| Hen of the Woods (Grifola frondosa) | Fruiting bodies | September – November |

| Morel Mushroom (Morchella spp.) | Fruiting bodies | April – May |

| Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | Young leaves, flowers | April – June (leaves), May – June (flowers) |

| Wild Ramps (Allium tricoccum) | Bulbs, young leaves | April – May (leaves), May – June (bulbs) |

| Wineberry (Rubus phoenicolasius) | Ripe berries | June – August |

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | Ripe fruits | August – October |

| Chanterelle Mushroom (Cantharellus spp.) | Fruiting bodies | July – September |

| Wild Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) | Ripe berries | July – August |

| American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | Ripe fruits | October – November |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | Berries, young leaves | April – May (leaves), August – September (berries) |

| Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) | Young shoots | April – May |

| Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) | Young leaves | March – May |

| Beach Plum (Prunus maritima) | Ripe fruits | August – September |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | Young leaves, seeds | May – July (leaves), August – September (seeds) |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.