The woods of Massachusetts hide tasty mushrooms like morels and chicken of the woods. In spring and fall, these mushrooms grow in wet woods and can sell for good money at farmers markets. They also taste great in soups and stir-fries.

The coast has its own goods, with edible seaweeds and shellfish in the shallow waters. Beach plums grow wild along sandy paths near the ocean. These sour fruits make yummy jams that locals love.

Hill areas have wild berries and healing plants all growing season. Blackberries, blueberries, and elderberries grow well in sunny open spots. Many people look for plants like goldenrod and mullein to help with health issues.

Learning to gather wild foods safely takes time but is worth it. Wild foods often have more good stuff in them than foods from the store.

As you scan the forest floor and stream banks for these valuable plants, your eyes will pass over countless interesting stones.

To make sure you can identify any interesting minerals you find along the way, Rock Chasing’s New England Rocks & Minerals Identification Field Guide is an invaluable companion. It ensures you will not overlook a different kind of natural treasure during your foraging adventures.

What We Cover In This Article:

- What Makes Foreageables Valuable

- Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

- The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

- Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

- When to Forage for Maximum Value

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

What Makes Foreageables Valuable

Some wild plants, mushrooms, and natural ingredients can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re selling them or using them at home, their worth often comes down to a few key things:

The Scarcer the Plant, the Higher the Demand

Some valuable forageables only show up for a short time each year, grow in hard-to-reach areas, or are very difficult to cultivate. That kind of rarity makes them harder to find and more expensive to buy.

Morels, truffles, and ramps are all good examples of this. They’re popular, but limited access and short growing seasons mean people are often willing to pay more.

A good seasonal foods guide can help you keep track of when high-value items appear.

You won’t believe how many incredible rocks and minerals you’ve walked past across New England without knowing their names.

This field guide makes it insanely easy to spot gems, minerals, and hidden treasures anywhere you explore.

📘 Check out the New England Field Guide Now →

What makes it different:

🚙 Field-tested across New England

📘 Heavy duty laminated pages resist dust, sweat, and water.

🧠 Zero fluff with clear visuals and straight-to-the-point info.

📍 Find hidden gems like Topaz, Amethyst, and beautiful crystals.

High-End Dishes Boost the Value of Ingredients

Wild ingredients that are hard to find in stores often catch the attention of chefs and home cooks. When something unique adds flavor or flair to a dish, it quickly becomes more valuable.

Truffles, wild leeks, and edible flowers are prized for how they taste and look on a plate. As more people try to include them in special meals, the demand—and the price—tends to rise.

You’ll find many of these among easy-to-identify wild mushrooms or herbs featured in fine dining.

Medicinal and Practical Uses Drive Forageable Prices Up

Plants like ginseng, goldenseal, and elderberries are often used in teas, tinctures, and home remedies. Their value comes from how they support wellness and are used repeatedly over time.

These plants are not just ingredients for cooking. Because people turn to them for ongoing use, the demand stays steady and the price stays high.

The More Work It Takes to Harvest, the More It’s Worth

Forageables that are hard to reach or tricky to harvest often end up being more valuable. Some grow in dense forests, need careful digging, or have to be cleaned and prepared before use.

Matsutake mushrooms are a good example, because they grow in specific forest conditions and are hard to spot under layers of leaf litter. Wild ginger and black walnuts, meanwhile, both require extra steps for cleaning and preparation before they can be used or sold.

All of that takes time, effort, and experience. When something takes real work to gather safely, buyers are usually willing to pay more for it.

Foods That Keep Well Are More Valuable to Buyers

Some forageables, like dried morels or elderberries, can be stored for months without losing their value. These longer-lasting items are easier to sell and often bring in more money over time.

Others, like wild greens or edible flowers, have a short shelf life and need to be used quickly. Many easy-to-identify wild greens and herbs are best when fresh, but can be dried or preserved to extend their usefulness.

Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

When you’re foraging for high-value plants, mushrooms, or other wild ingredients, every decision matters. Whether you’re selling at a farmers market or stocking your own pantry, simple mistakes can make your harvest less valuable or even completely worthless.

Harvesting at the Wrong Time

Harvesting at the wrong time can turn a valuable find into something no one wants. Plants and mushrooms have a short window when they’re at their best, and missing it means losing quality.

Morels, for example, shrink and dry out quickly once they mature, which lowers their weight and price. Overripe berries bruise in the basket and spoil fast, making them hard to store or sell.

Improper Handling After Harvest

Rough handling can ruin even the most valuable forageables. Crushed mushrooms, wilted greens, and dirty roots lose both their appeal and their price.

Use baskets or mesh bags to keep things from getting smashed and let air circulate. Keeping everything cool and clean helps your harvest stay fresh and look better for longer.

This is especially important for delicate items like wild roots and tubers that need to stay clean and intact.

Skipping Processing Steps

Skipping basic processing steps can cost you money. A raw harvest may look messy, spoil faster, or be harder to use.

For example, chaga is much more valuable when dried and cut properly. Herbs like wild mint or nettle often sell better when bundled neatly or partially dried. If you skip these steps, you may end up with something that looks unappealing or spoils quickly.

Collecting from the Wrong Area

Harvesting in the wrong place can ruin a good find. Plants and mushrooms pulled from roadsides or polluted ground may be unsafe, no matter how fresh they look.

Buyers want to know their food comes from clean, responsible sources. If a spot is known for overharvesting or damage, it can make the whole batch less appealing.

These suburbia foraging tips can help you find overlooked spots that are surprisingly safe and productive.

Not Knowing the Market

A rare plant isn’t valuable if nobody wants to buy it. If you gather in-demand species like wild ramps or black trumpets, you’re more likely to make a profit. Pay attention to what chefs, herbalists, or vendors are actually looking for.

Foraging with no plan leads to wasted effort and unsold stock. Keeping up with demand helps you bring home a profit instead of a pile of leftovers.

You can also brush up on foraging for survival strategies to identify the most versatile and useful wild foods.

The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

Some of the most sought-after wild plants and fungi here can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re foraging for profit or personal use, these are the ones worth paying attention to:

Highbush Blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum)

Highbush blueberries grow on woody shrubs reaching 6-12 feet tall, producing clusters of sweet blue-black berries with a dusty bloom on their surface. The berries have a distinctive crown shape at one end and contain tiny seeds. Their flavor ranges from sweet to tangy with bright summer notes.

The entire berry is edible and needs no special preparation. Look for bell-shaped white or pink flowers in spring and oval leaves that turn bright red in fall. Unlike poisonous nightshade berries, blueberries grow in clusters and have a crown on the bottom.

These berries sell well at markets due to their antioxidant properties. They contain compounds that help eye health and brain function. Fresh berries can be frozen whole or dried for later use in baking and trail mixes.

Hickory Nuts (Carya spp.)

Hickory nuts have thick husks that split open when ripe, revealing a hard, ridged shell with a sweet, buttery kernel inside. These nuts come from tall trees with compound leaves and bark that peels in long strips. The kernel has a rich flavor many people think tastes better than store-bought nuts.

Only the kernel inside is edible, and you need a hammer to crack the shell. The high oil content makes hickory nuts good for both eating and making oil. They can last up to two years when stored in a cool, dry place.

When looking for hickory nuts, check for the ridged shell and four-part husk. Avoid similar black walnuts, which have rounder shells and stronger flavor. Many traditional recipes from Appalachia use hickory nuts for their special taste.

Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus)

Jerusalem artichoke grows tall with sunflower-like blooms and has knobby underground tubers. The tubers are tan or reddish and look a bit like ginger root, though they belong to the sunflower family.

The part you’re after is the tuber, which has a nutty, slightly sweet flavor and a crisp texture when raw. You can roast, sauté, boil, or mash them like potatoes, and they hold their shape well in soups and stir-fries.

Some people experience gas or bloating after eating sunchokes due to the inulin they contain, so it’s a good idea to try a small amount first. Cooking them thoroughly can help reduce the chances of digestive discomfort.

Sunchokes don’t have many dangerous lookalikes, but it’s important not to confuse the plant with other sunflower relatives that don’t produce tubers. The above-ground part resembles a small sunflower, but it’s the knotted, underground tubers that are worth digging up.

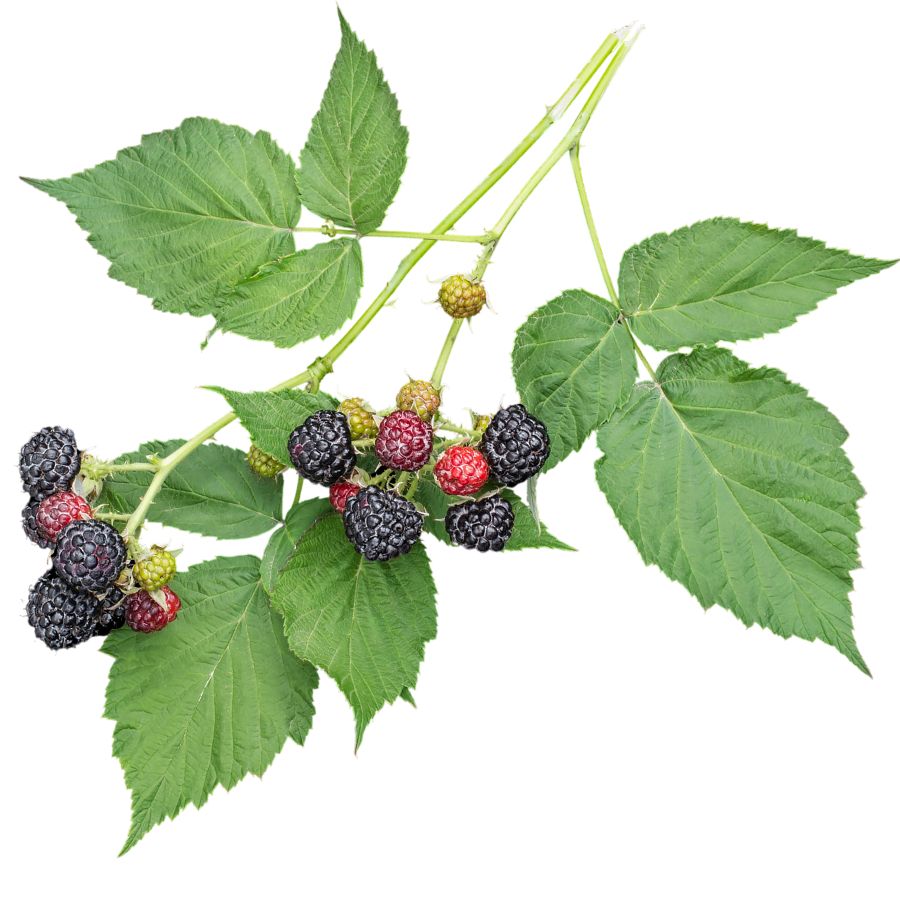

Wild Black Raspberries (Rubus occidentalis)

Wild black raspberries feature small clusters of shiny, black drupelets that form a hollow cap when picked. These berries grow on thorny canes that arch and sometimes root at the tips, creating thickets in woodland edges and old fields.

Their flavor is more intense than cultivated raspberries, with a perfect balance of sweetness and tartness that makes them prized for premium desserts and preserves.

The dark purple juice can stain fingers and clothing, often serving as evidence of a successful foraging trip. Unlike blackberries, which they resemble, black raspberries pull free from the plant, leaving a hollow center. Blackberries, by contrast, come off with the core still attached.

The entire berry is edible, though you should avoid the stems and leaves.

Ostrich Fern Fiddlehead (Matteuccia struthiopteris)

Ostrich fern fiddleheads are tightly coiled spirals with a U-shaped groove on the stem and papery brown scales. They taste like a mix of asparagus, green beans, and nuts, staying slightly crisp even when cooked. Harvest only young shoots less than 6 inches tall.

Telling them apart from other ferns is important since some ferns can make you sick. Look for brown papery scales and the U-shaped groove, other ferns have different patterns. Ostrich ferns also make straight fertile fronds in winter that look like ostrich feathers.

Always cook fiddleheads thoroughly before eating to avoid stomach problems. Chefs prize them for their short spring season and unique look. Many restaurants feature them as special menu items when available.

Elderberries (Sambucus canadensis)

Elderberries form large, flat-topped clusters on shrubs with compound leaves arranged opposite each other. These small purple berries taste sweet, tart, and slightly bitter, similar to blackberries with a grape-like quality. They have a distinct musky smell that gets stronger when cooked.

You must cook the berries after removing them from the stems, as raw elderberries can cause stomach upset. The flowers are safe to eat raw and make wonderful syrups and drinks. Never eat the stems, leaves, roots, or unripe berries as they contain harmful compounds.

Check for opposite leaf arrangement and flat berry clusters when identifying elderberry. This helps avoid toxic water hemlock, which has alternate leaves and different flower shapes.

The berries have become valuable for their immune-boosting properties and high vitamin C, creating demand among health-conscious buyers.

Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata)

With its silver-dusted leaves and small, speckled red fruits, autumn olive—also called silverberry or Japanese silverberry—has made its way into many thickets and field edges. The fruit is edible, tart, and slick-skinned, with a burst of sourness that mellows in cooked preparations.

People often turn autumn olive into jelly, sauces, or fermented beverages to tame the intense flavor. You can also dehydrate the berries into a powder for use in baked goods.

Some confuse it with Russian olive, which grows similar leaves but bears dry, yellow fruit instead. Stick to harvesting just the berries, as the rest of the plant doesn’t have any culinary use.

What makes autumn olive particularly interesting is its nitrogen-fixing ability, which helps it thrive where other plants struggle—but that same trait is also why it spreads so aggressively. Still, the fruit is safe and edible, and one of the few wild berries with such a high lycopene content.

Serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

Serviceberries grow as small trees or large shrubs across North America. Their white flowers bloom in clusters during spring, followed by dark purple berries that taste sweet with hints of almond. The berries have a unique texture that’s both juicy and slightly grainy.

These plants are easy to spot by their oval leaves with fine teeth along the edges. The bark appears smooth and gray on younger branches. When ripe, the berries turn deep purple or black.

The main challenge is telling serviceberries apart from other berry-producing shrubs. However, the distinctive flower clusters and leaf shape make identification fairly simple once you know what to look for.

Only the ripe berries are edible. Avoid eating the leaves, bark, or unripe fruit. The berries work great fresh, dried, or cooked into jams and pies.

If your kids keep asking, “What rock is this?”, here’s your answer.

🪨 300+ bright, kid-friendly photos

💦 Waterproof and built for outdoor adventures

🔍 Simple explanations made for young explorers

🌲 Helps kids learn, play, and explore outdoors

This durable field guide shows them exactly what they found, fast, fun, and frustration-free.

Wild Grape (Vitis labrusca)

Wild grapes have a strong, musky smell that’s quite different from store-bought varieties. The taste is intense and tart, with thick skins that can be quite sour.

The most important safety tip is avoiding lookalikes. Canada moonseed produces similar-looking clusters but has crescent-shaped seeds instead of round grape seeds. This difference is critical because moonseed is poisonous.

Wild grape leaves have three to five lobes and feel fuzzy underneath. The vines develop curly tendrils that help them climb. Grape clusters hang down from the vine in thick bunches.

Both the grapes and young leaves are edible. The grapes make excellent jelly, juice, or wine. Young grape leaves can be cooked and eaten.

These grapes are valuable because they produce large quantities of fruit and have many uses. They’re also relatively easy to process and preserve for winter eating.

Groundnut (Apios americana)

Groundnut is also called potato bean or Indian potato, and it grows as a climbing vine with clusters of pinkish-purple flowers. The part most people go for is the underground tuber, which looks a bit like a small, knobby chain of beads.

The flavor is richer than a regular potato, with a nutty, earthy taste and a dense, almost chestnut-like texture when cooked. It holds up well in soups and stews, or you can boil and mash it like a root vegetable.

Some people slice it thin and roast it until crisp, while others slow-cook it to bring out a sweeter taste. The vine also produces beans, but the root is what’s usually eaten.

There are a few vines that resemble groundnut, but many of those don’t have the same distinctive flower clusters or tend to lack the beadlike roots. Always make sure you’re digging up the right plant before cooking it.

American Hazelnut (Corylus americana)

Clusters of round, fringed husks tucked among bushy green leaves usually mean you have found American hazelnut, sometimes called American filbert. It grows as a wide, shrubby plant that spreads along forest edges, open woods, and overgrown fields.

The nuts inside are rich and buttery, with a firm texture that turns creamy when roasted or ground into flour. You can eat them raw, toss them into baked goods, or crush them into a thick, flavorful spread.

It helps to know the difference between American hazelnut and its close cousin, beaked hazelnut, which hides its nut inside a long, pointed husk. Both plants are safe to eat, but the shape of the husk makes it easy to tell which one you have.

Only the inner nut is gathered for food; the leafy husk and hard outer shell are tossed aside. If you leave them too long, local wildlife like squirrels will clear out the patch faster than you can.

Beach Plums (Prunus maritima)

Low-growing shrubs hug coastal areas, rarely reaching more than six feet tall. Beach plums develop thick, tangled branches that help them survive harsh ocean winds and salt spray.

What part you eat matters greatly with beach plums. The fruit flesh is perfectly safe and delicious when cooked with sugar. However, never eat the pits, leaves, or bark.

Finding beach plums is straightforward if you’re near the coast. They grow in sandy soil close to beaches and have small white flowers in early growing months. The oval leaves have serrated edges and appear slightly thick and waxy.

Beach plums look similar to other wild cherries, but their coastal location helps with identification. The fruits are usually larger than most wild cherries.

Their value comes from their unique habitat and intense flavor. Beach plums make outstanding jams and jellies that capture the essence of coastal living.

Sassafras (Sassafras albidum)

Sassafras is a small deciduous tree with bright green leaves that feel slightly mucilaginous when crushed. You can eat the young leaves raw or dried, and they develop a unique flavor, lightly citrusy, with a smooth texture when chewed.

People use the ground leaves as a thickener in soups and stews, especially in southern recipes. The bark and roots have a stronger taste and were historically brewed into teas with a deep, spicy profile.

There’s a caution with sassafras root: it contains safrole, which has been restricted from commercial food use due to safety studies. However, using a small amount occasionally in traditional preparations is still common in home kitchens.

The tree has a sweet, clove-like scent that sets it apart when the leaves or twigs are snapped. Its closest lookalikes lack that scent and don’t have the same combination of leaf shapes on a single branch.

Cattail Shoots and Roots (Typha latifolia)

Tall grass-like plants stand in shallow water with distinctive brown, sausage-shaped flower heads at the top. Cattails can grow eight feet tall or more, with long, flat leaves that feel smooth and sword-like. The young shoots taste similar to cucumber, while the roots have a starchy, potato-like flavor.

Cattails are among the easiest wetland plants to identify correctly. The brown cylindrical flower head sits above long, narrow leaves that grow straight up from the water. No poisonous plants share this exact appearance.

The challenge with cattails isn’t identification but knowing which parts to harvest. Young shoots that appear in spring are tender and mild. The roots provide starchy nutrition and can be dried and ground into flour.

Avoid the mature leaves and older stems, which become tough and fibrous. The flower heads are also edible at certain stages, but require specific timing.

Cattails earn their reputation as “supermarket of the swamp” because almost every part has a use. They provide carbohydrates, vitamins, and can sustain people during food shortages. The abundance and reliability of cattails make them extremely valuable for wilderness survival.

Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva)

Bright orange flowers known as daylily, tiger lily, or ditch lily can sometimes be mistaken for other plants that are not safe to eat. True daylilies have long, blade-like leaves that grow in clumps at the base and a hollow flower stem, while their toxic lookalikes often have solid stems or different leaf patterns.

When it comes to flavor, daylily buds have a crisp texture and a mild taste that some people compare to green beans or asparagus. The flowers are tender and slightly sweet, which makes them popular for tossing into salads or lightly stir-frying.

Most people use the unopened flower buds in cooking, but the young shoots and tuber-like roots are also gathered for food. Always make sure you are harvesting from clean areas, because roadside plants can carry pollutants that are not safe to eat.

A few important cautions come with daylilies, since some people experience digestive upset after eating large amounts. Start by tasting a small quantity first to see how your body reacts before eating more.

Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta)

Wood sorrel features delicate, heart-shaped leaves that fold along their center line and resemble tiny clovers. The leaves grow in groups of three and produce small yellow flowers. Its distinctive lemony flavor makes it a favorite wild snack among foragers.

The entire plant is edible, including leaves, flowers, and seed pods. The leaves contain oxalic acid, giving them a pleasant sour taste similar to lemons. This makes them perfect for adding to salads or as a trail snack.

When identifying wood sorrel, look for the classic folded, heart-shaped leaflets that close at night or during rain. Unlike clover, wood sorrel has a more pronounced sour taste and thinner stems.

Many traditional cultures have used wood sorrel as a thirst quencher and vitamin C source. The plant can be found in woodlands, lawns, and garden beds throughout North America.

Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica)

Stinging nettle grows upright with serrated, dark green leaves covered in tiny hairs that deliver a burning sting when touched with bare skin. These plants typically reach 3-4 feet tall and grow in dense patches in moist areas near streams or in rich soil.

To harvest safely, wear gloves and collect young plants in spring when they’re most tender. Once cooked or dried, the stinging properties disappear completely.

Nutritionally, nettles are powerhouses containing more protein than most plants, along with iron, calcium, and vitamins A and C. The leaves make excellent tea, soup, or can replace spinach in most recipes.

Stinging nettle might be confused with wood nettle or clearweed, but its opposite leaf arrangement and intense sting are distinctive identifiers. The entire above-ground portion is edible when properly prepared, making it one of the most nutritious wild greens available.

Burdock Root (Arctium minus)

Large, wavy-edged leaves and purple thistle-like flowers make burdock a distinctive plant in the wild. The root, which can grow up to three feet long, has a crisp texture and earthy, sweet flavor similar to artichoke hearts when cooked. First-year plants produce only a rosette of leaves, while second-year plants develop tall flowering stalks.

Burdock root is best harvested from first-year plants in fall or early spring when the roots store the most nutrients. The outer layer must be peeled away to reveal the white flesh inside.

Only the root and young leaf stems are considered edible parts. Mature leaves become too bitter for consumption.

In Japanese cuisine, burdock root is known as “gobo” and is a staple vegetable. Its deep taproot helps break up compacted soil and brings nutrients to the surface, making it valuable for both foragers and the ecosystem.

Black Trumpet Mushrooms (Craterellus fallax)

Black trumpet mushrooms appear as dark, hollow, trumpet-shaped fungi growing in clusters on forest floors. Their thin, wrinkled caps curve downward, resembling miniature black trumpets or funnels. These mushrooms have a rich, smoky aroma and complex flavor, often described as earthy with hints of black truffle.

What makes black trumpets particularly valuable is their distinctive appearance, with few dangerous lookalikes, making them relatively safe for beginning mushroom hunters. They typically grow near oak, beech, or pine trees in damp, shady areas.

The entire mushroom is edible from base to rim. Their dark color helps them blend into forest debris, making them challenging to spot despite being common in many woodlands.

After proper identification, black trumpets can be dried easily to preserve their flavor. Their umami-rich taste intensifies when dried, allowing them to add depth to soups, sauces, and pasta dishes even months after foraging.

Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

Some parts of the state are better than others when it comes to finding valuable wild plants and mushrooms. Here are the different places where you’re most likely to have luck:

| Plant | Locations |

|---|---|

| Highbush Blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum) | – Blue Hills Reservation – Myles Standish State Forest – Great Brook Farm State Park |

| Hickory Nuts (Carya spp.) | – Wachusett Reservoir woodlands – Quabbin Reservoir area – Georgetown-Rowley State Forest |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | – Connecticut River greenways – Mount Holyoke Range – Sudbury River floodplains |

| Wild Black Raspberries (Rubus occidentalis) | – Breakheart Reservation – Harold Parker State Forest – Montague Plains Wildlife Management Area |

| Fiddlehead Ferns – Ostrich Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) | – Housatonic River Valley – Mount Greylock foothills – Deerfield River banks |

| Elderberries (Sambucus canadensis) | – Hopkinton State Park – Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge buffer – Ashfield area hedgerows |

| Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) | – Nobscot Hill woodlands – Hadley farmland edges – Wrentham State Forest |

| Serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.) | – Middlesex Fells Reservation – Mount Watatic slopes – Amherst College Wildlife Sanctuary |

| Wild Grape (Vitis labrusca) | – Concord River banks – Holyoke Range trails – Rehoboth woodland edges |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | – Great Meadows near Concord – Sudbury Valley Trustees lands – Hatfield wet meadows |

| American Hazelnut (Corylus americana) | – Montague State Forest – Ware River watershed – Sherborn hedgerows |

| Beach Plums (Prunus maritima) | – Cape Cod Bay dunes – Westport coastal thickets – Nantasket Beach shrublands |

| Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) | – Upton State Forest – Norwottuck Rail Trail woods – Petersham oak groves |

| Cattail Shoots and Roots (Typha latifolia) | – Charles River wetlands – Northfield Marsh – Ipswich River Wildlife Sanctuary outskirts |

| Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) | – Groton conservation meadows – Berkshire backyard trails – Taunton overgrown fields |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta) | – Acton arboretum – Amherst roadside trails – Boxford conservation land |

| Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) | – Millers River greenbelt – Sunderland hedgerows – Franklin County woodland clearings |

| Burdock Root (Arctium minus) | – Northampton bike paths – Somerville community edges – West Springfield abandoned lots |

| Black Trumpet Mushrooms (Craterellus fallax) | – Mohawk Trail woodlands – Pelham mossy valleys – Conway shaded slopes |

When to Forage for Maximum Value

Every valuable wild plant or mushroom has its season. Here’s a look at the best times for harvest:

| Plants | Valuable Parts | Best Harvest Season |

|---|---|---|

| Highbush Blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum) | Ripe berries | July – August |

| Hickory Nuts (Carya spp.) | Nuts inside mature shells | September – October |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | Underground tubers | October – November, March – April (before sprouting) |

| Wild Black Raspberries (Rubus occidentalis) | Ripe berries | June – July |

| Fiddlehead Ferns – Ostrich Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) | Young coiled fronds (fiddleheads) | April – May |

| Elderberries (Sambucus canadensis) | Ripe berries, flowers | Flowers: June – July, Berries: August – September |

| Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) | Ripe berries | September – October |

| Serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.) | Ripe berries | June |

| Wild Grape (Vitis labrusca) | Ripe grapes, young leaves | Leaves: May – June, Grapes: August – September |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | Underground tubers | October – November |

| American Hazelnut (Corylus americana) | Nuts inside husks | August – September |

| Beach Plums (Prunus maritima) | Ripe plums | August – September |

| Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) | Roots (for tea), young leaves | Leaves: May – June, Roots: October – November |

| Cattail Shoots and Roots (Typha latifolia) | Young shoots, roots, pollen | Shoots: May – June, Roots: September – October, Pollen: June – July |

| Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) | Young shoots, flower buds, tubers | Shoots: April – May, Buds: June – July, Tubers: October |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta) | Tender leaves, flowers, seed pods | April – October |

| Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) | Young leaves (before flowering) | April – June |

| Burdock Root (Arctium minus) | First-year taproots | September – November |

| Black Trumpet Mushrooms (Craterellus fallax) | Fruiting body (whole mushroom) | August – October |