You can make extra cash by knowing what to look for in Kansas forests, prairies, and meadows. Our state offers natural treasures that many people walk past without noticing. These hidden gems wait throughout the Sunflower State.

Learning to spot valuable forageables takes some practice but is worth the effort. The satisfaction of finding something special in nature feels rewarding. Kansas landscapes provide perfect conditions for many sought-after natural items.

Spring and fall bring the best opportunities for foraging in Kansas. The weather makes outdoor exploration comfortable and enjoyable during these seasons. Many valuable items appear most abundantly as seasons change.

Local knowledge helps identify the best locations across our state. Some spots remain productive year after year if harvested responsibly. Conservation practices ensure these resources remain available for future generations.

Once you begin spotting a few of these edible plants, you realize just how much is growing all around. Kansas offers a surprising range of forageables with real value in the kitchen and beyond. The key is learning how to see what’s already there, waiting to be gathered.

What We Cover In This Article:

- What Makes Foreageables Valuable

- Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

- The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

- Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

- When to Forage for Maximum Value

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

What Makes Foreageables Valuable

Some wild plants, mushrooms, and natural ingredients can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re selling them or using them at home, their worth often comes down to a few key things:

The Scarcer the Plant, the Higher the Demand

Some valuable forageables only show up for a short time each year, grow in hard-to-reach areas, or are very difficult to cultivate. That kind of rarity makes them harder to find and more expensive to buy.

Morels, truffles, and ramps are all good examples of this. They’re popular, but limited access and short growing seasons mean people are often willing to pay more.

A good seasonal foods guide can help you keep track of when high-value items appear.

High-End Dishes Boost the Value of Ingredients

Wild ingredients that are hard to find in stores often catch the attention of chefs and home cooks. When something unique adds flavor or flair to a dish, it quickly becomes more valuable.

Truffles, wild leeks, and edible flowers are prized for how they taste and look on a plate. As more people try to include them in special meals, the demand—and the price—tends to rise.

You’ll find many of these among easy-to-identify wild mushrooms or herbs featured in fine dining.

Medicinal and Practical Uses Drive Forageable Prices Up

Plants like ginseng, goldenseal, and elderberries are often used in teas, tinctures, and home remedies. Their value comes from how they support wellness and are used repeatedly over time.

These plants are not just ingredients for cooking. Because people turn to them for ongoing use, the demand stays steady and the price stays high.

The More Work It Takes to Harvest, the More It’s Worth

Forageables that are hard to reach or tricky to harvest often end up being more valuable. Some grow in dense forests, need careful digging, or have to be cleaned and prepared before use.

Matsutake mushrooms are a good example, because they grow in specific forest conditions and are hard to spot under layers of leaf litter. Wild ginger and black walnuts, meanwhile, both require extra steps for cleaning and preparation before they can be used or sold.

All of that takes time, effort, and experience. When something takes real work to gather safely, buyers are usually willing to pay more for it.

Foods That Keep Well Are More Valuable to Buyers

Some forageables, like dried morels or elderberries, can be stored for months without losing their value. These longer-lasting items are easier to sell and often bring in more money over time.

Others, like wild greens or edible flowers, have a short shelf life and need to be used quickly. Many easy-to-identify wild greens and herbs are best when fresh, but can be dried or preserved to extend their usefulness.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

When you’re foraging for high-value plants, mushrooms, or other wild ingredients, every decision matters. Whether you’re selling at a farmers market or stocking your own pantry, simple mistakes can make your harvest less valuable or even completely worthless.

Harvesting at the Wrong Time

Harvesting at the wrong time can turn a valuable find into something no one wants. Plants and mushrooms have a short window when they’re at their best, and missing it means losing quality.

Morels, for example, shrink and dry out quickly once they mature, which lowers their weight and price. Overripe berries bruise in the basket and spoil fast, making them hard to store or sell.

Improper Handling After Harvest

Rough handling can ruin even the most valuable forageables. Crushed mushrooms, wilted greens, and dirty roots lose both their appeal and their price.

Use baskets or mesh bags to keep things from getting smashed and let air circulate. Keeping everything cool and clean helps your harvest stay fresh and look better for longer.

This is especially important for delicate items like wild roots and tubers that need to stay clean and intact.

Skipping Processing Steps

Skipping basic processing steps can cost you money. A raw harvest may look messy, spoil faster, or be harder to use.

For example, chaga is much more valuable when dried and cut properly. Herbs like wild mint or nettle often sell better when bundled neatly or partially dried. If you skip these steps, you may end up with something that looks unappealing or spoils quickly.

Collecting from the Wrong Area

Harvesting in the wrong place can ruin a good find. Plants and mushrooms pulled from roadsides or polluted ground may be unsafe, no matter how fresh they look.

Buyers want to know their food comes from clean, responsible sources. If a spot is known for overharvesting or damage, it can make the whole batch less appealing.

These suburbia foraging tips can help you find overlooked spots that are surprisingly safe and productive.

Not Knowing the Market

A rare plant isn’t valuable if nobody wants to buy it. If you gather in-demand species like wild ramps or black trumpets, you’re more likely to make a profit. Pay attention to what chefs, herbalists, or vendors are actually looking for.

Foraging with no plan leads to wasted effort and unsold stock. Keeping up with demand helps you bring home a profit instead of a pile of leftovers.

You can also brush up on foraging for survival strategies to identify the most versatile and useful wild foods.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

Some of the most sought-after wild plants and fungi here can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re foraging for profit or personal use, these are the ones worth paying attention to:

Prairie Turnip (Pediomelum esculentum)

Prairie turnip grows in dry grasslands with a purple flower cluster on a tall stem. Underground sits a starchy tuber about the size of a chicken egg. Native Americans have used this plant as food for thousands of years.

The white tuber is what you eat. Dig carefully around the plant when harvesting. You can eat it raw, but most people cook it to improve the mild flavor.

Some folks mistake American vetch for prairie turnip because of similar purple flowers. To tell them apart, look for the turnip’s three-part leaves and woody stem connecting to the tuber.

This plant contains lots of protein, carbs, and vitamin C. Many people value it both for survival skills and to connect with traditional foods of the past.

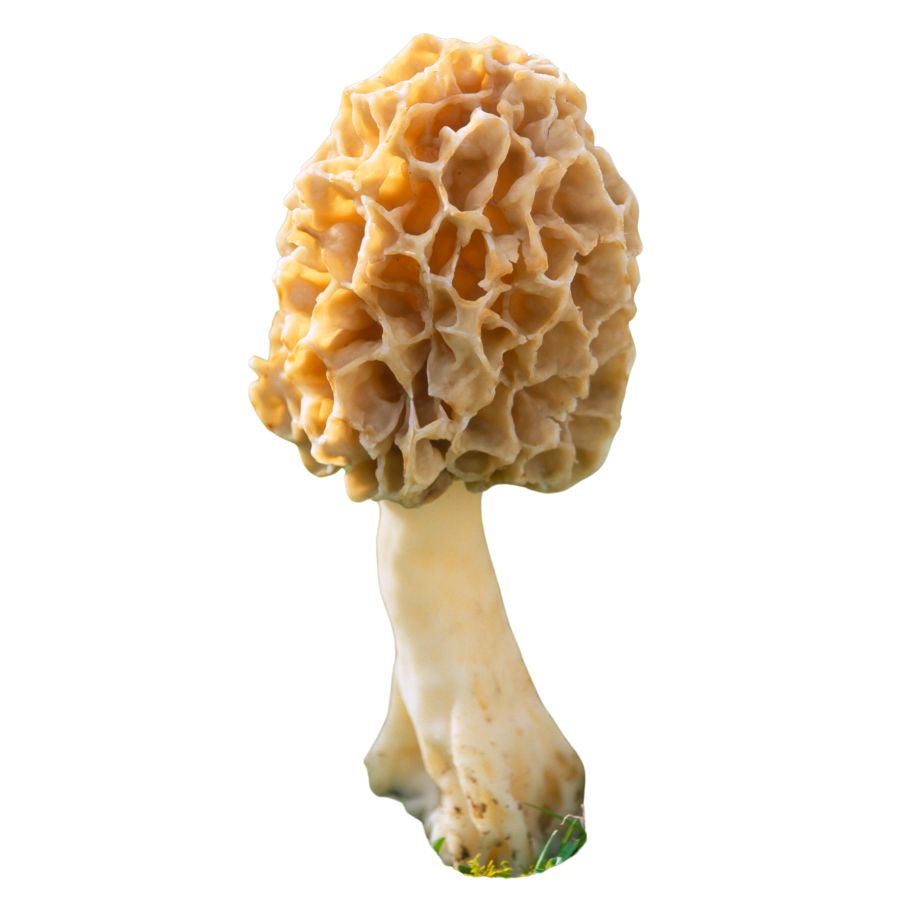

Morel Mushroom (Morchella esculenta)

The honeycomb pattern makes morels easy to spot in the forest. Their cone-shaped caps have deep pits and ridges, with colors from pale tan to dark brown. Cut one open and you’ll find it’s completely hollow inside.

These mushrooms show up in early spring, often near dead elm trees, old apple orchards, or recently disturbed soil. Always cook morels thoroughly before eating them – raw ones can make you sick.

Watch out for false morels. These dangerous lookalikes have caps that hang loosely around the stem and aren’t hollow inside. Always slice your morels lengthwise to check.

Chefs pay top dollar for morels because of their rich, nutty flavor. Since they can’t be easily grown on farms and only appear for a short time each year, finding them feels like striking gold.

Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus)

Jerusalem artichoke grows tall with sunflower-like blooms and has knobby underground tubers. The tubers are tan or reddish and look a bit like ginger root, though they belong to the sunflower family.

The part you’re after is the tuber, which has a nutty, slightly sweet flavor and a crisp texture when raw. You can roast, sauté, boil, or mash them like potatoes, and they hold their shape well in soups and stir-fries.

Some people experience gas or bloating after eating sunchokes due to the inulin they contain, so it’s a good idea to try a small amount first. Cooking them thoroughly can help reduce the chances of digestive discomfort.

Sunchokes don’t have many dangerous lookalikes, but it’s important not to confuse the plant with other sunflower relatives that don’t produce tubers. The above-ground part resembles a small sunflower, but it’s the knotted, underground tubers that are worth digging up.

Hen of the Woods (Grifola frondosa)

Clusters of grayish-brown caps make Hen of the Woods look like a fluffed-up chicken at the base of oak trees. Some grow huge, weighing over 40 pounds. The flesh feels meaty and smells earthy when cooked.

The entire mushroom except the tough base can be eaten. Harvest by cutting above this base, leaving some behind so it can grow again next year.

Many health-minded folks seek this mushroom for its immune-boosting properties. Its rich flavor holds up well to many cooking methods.

Hen of the Woods has few dangerous lookalikes. Berkeley’s Polypore looks similar but grows differently and is also safe to eat. Black-staining polypore might fool you, but it turns black when cut. Look for Hen of the Woods in fall – it often returns to the same tree for many years.

Wild Onion (Allium canadense)

Slender green stalks topped with clusters of tiny white or pink flowers mark wild onion patches in open fields and meadows. The entire plant smells strongly of onion when crushed, confirming its identity. Underground, small bulbs anchor the plants in loose, rich soil.

All parts of wild onion can be eaten, from the bulbs to the hollow leaves to the flower heads. The flavor ranges from mild to strong depending on growing conditions and time of year.

Several poisonous plants look similar, especially death camas and star-of-Bethlehem. The onion smell is your best safety check – toxic lookalikes never smell like onions.

Harvest by gently pulling or digging up the bulbs, which are smaller than store-bought onions but pack more flavor. Wild onions add zest to salads, soups, and cooked dishes just like their garden relatives. Many foragers value them as one of the earliest wild edibles available after winter, providing vitamin C and minerals when few other plants are ready to harvest.

Wild Plum (Prunus americana)

Wild plum, also called American plum or river plum, produces small round fruits that range in color from yellow to deep red when ripe. The skin is slightly tart, but the flesh is soft, juicy, and sweet with a hint of spice.

You can eat the fruit raw or turn it into jellies, sauces, or wines—its natural pectin makes it ideal for preserves. Just avoid the seeds and leaves, which contain compounds that can release cyanide when crushed or chewed.

Its bark is rough and dark, and the branches often have short, sharp spines. The plant’s simple oval leaves and white spring flowers help distinguish it from less edible lookalikes like black cherry, which has longer, narrower leaves with a more bitter fruit.

If the fruit has a strong bitter almond smell when crushed, steer clear—it might be a different species altogether. American plum fruit clusters tend to be smaller and more tightly packed than those of cultivated varieties.

Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus)

Oyster mushrooms fan out from dead trees in shelf-like clusters that truly resemble their seafood namesake. Their caps range from white to gray to brown, with short stems and gills running down their sides. They feel smooth and somewhat rubbery when fresh.

These fungi grow on many hardwood trees, especially after rainy periods in spring and fall. Unlike some wild mushrooms, oysters are fairly easy to identify and have few dangerous lookalikes.

What makes them special to foragers is their mild, slightly sweet flavor that works well in many dishes. Some people even notice a hint of anise or seafood in their taste.

All parts except the tough base of the stem are edible. Simply tear the mushrooms into strips for cooking – they don’t need much prep. Their popularity comes from both their taste and their ability to absorb flavors in cooking while keeping a pleasant texture.

Mulberry (Morus rubra)

Sweet, juicy, and often overlooked, mulberries are one of the easiest wild berries to recognize. Known by names like white mulberry and red mulberry, these trees produce small, blackberry-like fruits that range from pale pink to deep purple.

The berries have a soft, almost melting texture with a mild tartness behind the sugar. You can eat them fresh by the handful, bake them into pies, or simmer them down into homemade jams and syrups.

While the fruits are safe and delicious when ripe, you should avoid eating the unripe berries or any part of the tree’s sap, which can cause stomach upset. It is also worth knowing that mulberries are delicate and bruise easily when picked, so handle them gently.

Red osier dogwood and some honeysuckles can produce berries that look similar from a distance, but true mulberries grow singly or in loose clusters along the branches and have a distinctive leaf shape that sets them apart. Always double-check the leaf texture and berry arrangement before eating any wild fruits.

Burdock (Arctium minus)

Burdock, also known as burrweed or beggar’s buttons, grows large, floppy leaves and produces clusters of sticky seed heads that cling to clothing and fur. The plant can easily tower over you once it matures, especially when the thick stalks shoot up.

The root is the main edible part and has a crisp texture with a mild, sweet, slightly earthy flavor when cooked. You should avoid eating the leaves or seed heads, as they tend to be unpleasantly bitter and tough even when young.

When you cook burdock root, it works well sliced thin and stir-fried, boiled into soups, or simmered with other vegetables to soak up savory flavors. Peeling the root before cooking can help soften the flavor and improve the texture.

It is important to watch out for lookalikes like foxglove and woolly mullein, which can grow similarly large leaves at the base. True burdock leaves have a whitish, fuzzy underside and strong, fibrous stems that are solid rather than hollow.

Common Chicory (Cichorium intybus)

Chicory has bright blue flowers that open in the morning and close by afternoon. Its jagged leaves grow in a rosette close to the ground and can resemble dandelion leaves, but dandelions don’t have the same thick, hairy stems.

The leaves are bitter and slightly earthy, often compared to dandelion greens but with a stronger flavor. You can blanch or sauté them to mellow the bitterness, or chop them raw into salads if you like a sharper bite.

Its roots are the most commonly used part, especially when roasted and ground to mix into coffee or brewed as a caffeine-free drink on their own. They’re dense and woody, and once roasted, they take on a toasty, nutty flavor that balances well with richer foods.

Avoid confusing chicory with wild lettuce, which can grow in similar areas but has a milky sap and a more unpleasant taste. Chicory doesn’t have any toxic lookalikes, but the strong bitterness of mature leaves can be off-putting if you’re not expecting it.

Groundnut (Apios americana)

Groundnut is also called potato bean or Indian potato, and it grows as a climbing vine with clusters of pinkish-purple flowers. The part most people go for is the underground tuber, which looks a bit like a small, knobby chain of beads.

The flavor is richer than a regular potato, with a nutty, earthy taste and a dense, almost chestnut-like texture when cooked. It holds up well in soups and stews, or you can boil and mash it like a root vegetable.

Some people slice it thin and roast it until crisp, while others slow-cook it to bring out a sweeter taste. The vine also produces beans, but the root is what’s usually eaten.

There are a few vines that resemble groundnut, but many of those don’t have the same distinctive flower clusters or tend to lack the beadlike roots. Always make sure you’re digging up the right plant before cooking it.

Black Trumpet Mushroom (Craterellus fallax)

Black trumpets peek from forest floors like dark, hollow funnels often hidden among fallen leaves. These mushrooms grow in wavy clusters, colored deep brown to nearly black, with a velvety texture. Their trumpet-like shape gives them their common name.

Finding these woodland treasures takes a trained eye since they blend perfectly with forest debris. Once spotted, you’ll often discover many more nearby, especially under oak and beech trees in summer and fall.

No poisonous mushrooms closely resemble black trumpets, making them a relatively safe choice for beginner foragers. The entire mushroom is edible from top to bottom.

Many chefs consider black trumpets among the finest wild mushrooms because of their rich, smoky flavor and fruity aroma similar to apricots. They dry exceptionally well, actually intensifying their flavor. When rehydrated, they can add depth to soups, sauces, and egg dishes. Their scarcity and difficulty to find add to their special status among mushroom hunters.

Gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum)

Sweet-tart gooseberries grow on thorny bushes along forest edges. These marble-sized fruits hang like tiny lanterns, starting green and ripening to purple or red. You can see veins through their skin and some have tiny bristles.

When picking gooseberries, wear gloves to protect against sharp thorns. The entire berry is good to eat, though some people remove the blossom end first.

These berries work wonderfully in jams, pies, or eaten fresh when fully ripe. Both wildlife and humans seek them out for their bright flavor.

The bushes have lobed leaves similar to currants, which are related but don’t have thorns. Look for gooseberries in partly shaded spots with damp soil, often near streams or in forest openings. They pack lots of vitamin C, antioxidants, and fiber into their small packages.

Mallow (Malva neglecta)

Mallow, often called common mallow or cheeseweed, grows low to the ground and spreads with round, crinkled leaves that look a bit like tiny lily pads. It produces small pale purple or pink flowers with five delicate petals, and the seed pods are shaped like little green wheels.

The leaves, flowers, and immature seed pods of mallow are all edible, offering a mild, slightly sweet flavor and a soft, somewhat mucilaginous texture. Some people add the leaves to salads, toss them into soups for thickening, or quickly sauté them with garlic for a simple side dish.

When gathering mallow, make sure you do not confuse it with young deadly nightshade plants, which can sometimes grow in similar weedy areas but have very different flower and fruit structures. Mallow is safe to eat, but it tends to absorb pollutants from the soil, so be cautious about harvesting from roadsides or contaminated areas.

An interesting thing about mallow is that it was traditionally used for soothing sore throats and irritated skin because of its natural slimy quality. If you are foraging for food and medicine, mallow is a versatile and easy plant to start with once you are confident in your identification.

Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

Wild strawberry, sometimes called Virginia strawberry or mountain strawberry, grows low to the ground with three-part leaves that have jagged edges. The small white flowers with yellow centers eventually give way to tiny, bright red fruits nestled close to the soil.

The fruits are sweet with a burst of tartness, and their texture is much softer than the large cultivated strawberries you find in stores. You can eat them raw, mix them into jams, or bake them into pies for a rich, fruity flavor.

Wild strawberry can sometimes be confused with mock strawberry, which has similar leaves but produces dry, flavorless fruits and yellow flowers instead of white. Always check the flower color and taste a small piece before collecting more.

Only the berries and the tender young leaves of wild strawberry are edible, with the leaves often brewed into teas. Be careful not to overharvest because these plants grow slowly and support plenty of small wildlife.

Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album)

Lamb’s quarters, also called wild spinach and pigweed, has soft green leaves that often look dusted with a white, powdery coating. The leaves are shaped a little like goose feet, with slightly jagged edges and a smooth underside that feels almost velvety when you touch it.

A few plants can be confused with lamb’s quarters, like some types of nightshade, but true lamb’s quarters never have berries and its leaves are usually coated in that distinctive white bloom. Always check that the stems are grooved and not round and smooth like the poisonous lookalikes.

When you taste lamb’s quarters, you will notice it has a mild, slightly nutty flavor that gets richer when cooked. The young leaves, tender stems, and even the seeds are all edible, but you should avoid eating the older stems because they become tough and stringy.

People often sauté lamb’s quarters like spinach, blend it into smoothies, or dry the leaves for later use in soups and stews. It is also rich in oxalates, so you will want to cook it before eating large amounts to avoid any problems.

Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia polyacantha)

Flat, green, oval-shaped pads covered in clusters of needle-like spines make up the prickly pear cactus. During summer, vibrant yellow, orange, or pink flowers bloom on the edges of these pads, later developing into purple-red fruits.

The fruits and pads are both edible, but you must remove all spines and tiny hair-like prickles called glochids first. Wear thick gloves when handling them!

People use prickly pear in many ways – the pads (called nopales) are sliced and cooked like vegetables, while the sweet fruits make excellent jams, jellies, and drinks.

Look for these cacti in dry, sunny areas with well-drained soil. They grow throughout the western and southwestern United States. Rich in vitamin C, fiber, and antioxidants, prickly pear has been used as both food and medicine by indigenous peoples for centuries. Their ability to thrive in harsh conditions makes them a reliable wild food source.

Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

Some parts of the state are better than others when it comes to finding valuable wild plants and mushrooms. Here are the different places where you’re most likely to have luck:

| Plant | Locations |

|---|---|

| Prairie Turnip (Pediomelum esculentum) | – Konza Prairie, Riley County – Mitchell County uplands near Beloit – Smoky Hills bluffs in Ellsworth County |

| Morel Mushroom (Morchella esculenta) | – Kansas River bottomlands near Topeka – Hardwood stands in Johnson County – Big Blue River floodplain near Manhattan |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | – Flint Hills roadside edges – Riparian margins of the Neosho River near Iola – Disturbed fields around Hays |

| Hen of the Woods (Grifola frondosa) | – Oak woods near Clinton Lake Wildlife Area – Riparian woodlands in western Lawrence – Bottomland woods along the Marais des Cygnes River |

| Wild Onion (Allium canadense) | – Flint Hills hilltops in Chase County – Prairie margins in Sedgwick County – Terry Johnson Wildlife Area near Olathe |

| Wild Plum (Prunus americana) | – Brushy thickets along Walnut River near El Dorado – Streambanks in Nemaha County – Draws near Topeka city outskirts |

| Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) | – Fallen elm logs at Kaw River Park in Topeka – Willow groves near Wakarusa River in Lawrence – Cottonwood stands by Emporia city limits |

| Mulberry (Morus rubra) | – Old farmsteads in Douglas County – Riparian thickets along Solomon River – Parkland borders in Salina |

| Burdock (Arctium minus) | – Abandoned fields near west Wichita – Roadside ditches in Lyon County – Vacant areas in north Manhattan |

| Common Chicory (Cichorium intybus) | – Prairie road edges in Marion County – Highway shoulders near Hiawatha – Field boundaries around Newton |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | – Kansas River cane breaks near Eudora – Riparian zones by Little Arkansas River in Halstead – Bottomlands near Baldwin City |

| Black Trumpet Mushroom (Craterellus fallax) | – Shaded oak woods near Council Grove – Moist hillsides in Crawford County – Elm-poplar stands in Douglas County |

| Gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum) | – Woodland borders in Jefferson County – Creekside shade in Franklin County – Ravine slopes near Basehor |

| Mallow (Malva neglecta) | – Salina riverfront lots – Waste ground near Great Bend – Sidewalk edges in Hutchinson |

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) | – Prairie gaps in Flint Hills near Matfield Green – Woodland fringes by Baldwin – Trail margins in north Topeka |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | – Edge fields in Riley County – Disturbed prairie in Emporia outskirts – Construction lots in Olathe |

| Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia polyacantha) | – Smoky Hills west of Salina – Glade areas in Barton County – Limestone ridges in Wilson County |

When to Forage for Maximum Value

Every valuable wild plant or mushroom has its season. Here’s a look at the best times for harvest:

| Plants | Valuable Parts | Best Harvest Season |

|---|---|---|

| Prairie turnip (Pediomelum esculentum) | Tubers | June – July |

| Morel mushroom (Morchella esculenta) | Fruiting bodies | April – May |

| Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | Tubers | October – November |

| Hen of the woods (Grifola frondosa) | Fruiting bodies | September – November |

| Wild onion (Allium canadense) | Bulbs, leaves | April – May (leaves), June – July (bulbs) |

| Wild plum (Prunus americana) | Ripe fruits | July – August |

| Oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) | Fruiting bodies | April – May, September – November |

| Mulberry (Morus rubra) | Ripe fruits | May – June |

| Burdock (Arctium minus) | Roots (first-year), young stalks | March – April (stalks), October – November (roots) |

| Common chicory (Cichorium intybus) | Young leaves, roots | April – May (leaves), October – November (roots) |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | Tubers, seeds | September – November (tubers), October (seeds) |

| Black trumpet mushroom (Craterellus fallax) | Fruiting bodies | August – October |

| Gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum) | Ripe fruits | June – July |

| Mallow (Malva neglecta) | Young leaves, immature fruits | April – June |

| Wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) | Ripe fruits | May – June |

| Lamb’s quarters (Chenopodium album) | Young leaves, seeds | April – June (leaves), August – September (seeds) |

| Prickly pear cactus (Opuntia polyacantha) | Ripe fruits (tunas), young pads (nopales) | May – June (pads), August – September (fruits) |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.