Delaware’s forests, fields, and wetlands are full of natural treasures you can collect. Many plants and fungi growing wild throughout the state can be worth good money. Local chefs, herbalists, and craft makers often pay well for fresh, wild-harvested items.

Certain mushrooms, like morels and chicken of the woods, are highly valued by restaurants. Black walnuts and wild berries fetch nice prices at farmers markets too.

Knowing where to look makes all the difference when hunting valuable plants. Some spots in northern Delaware near the Piedmont region hold different treasures than the coastal areas in the south. Each season brings new foraging opportunities across our small but diverse state.

Learning to identify valuable species takes practice but pays off. Ramps, sassafras root, and spicebush berries are examples of native plants that people will buy. The spring and fall seasons typically offer the most valuable finds throughout Delaware’s varied landscapes.

Delaware might be small, but its edible landscape is broader than you’d think. There’s a lot more to uncover once you start seeing what’s really growing around you.

What We Cover In This Article:

- What Makes Foreageables Valuable

- Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

- The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

- Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

- When to Forage for Maximum Value

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

What Makes Foreageables Valuable

Some wild plants, mushrooms, and natural ingredients can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re selling them or using them at home, their worth often comes down to a few key things:

The Scarcer the Plant, the Higher the Demand

Some valuable forageables only show up for a short time each year, grow in hard-to-reach areas, or are very difficult to cultivate. That kind of rarity makes them harder to find and more expensive to buy.

Morels, truffles, and ramps are all good examples of this. They’re popular, but limited access and short growing seasons mean people are often willing to pay more.

A good seasonal foods guide can help you keep track of when high-value items appear.

High-End Dishes Boost the Value of Ingredients

Wild ingredients that are hard to find in stores often catch the attention of chefs and home cooks. When something unique adds flavor or flair to a dish, it quickly becomes more valuable.

Truffles, wild leeks, and edible flowers are prized for how they taste and look on a plate. As more people try to include them in special meals, the demand—and the price—tends to rise.

You’ll find many of these among easy-to-identify wild mushrooms or herbs featured in fine dining.

Medicinal and Practical Uses Drive Forageable Prices Up

Plants like ginseng, goldenseal, and elderberries are often used in teas, tinctures, and home remedies. Their value comes from how they support wellness and are used repeatedly over time.

These plants are not just ingredients for cooking. Because people turn to them for ongoing use, the demand stays steady and the price stays high.

The More Work It Takes to Harvest, the More It’s Worth

Forageables that are hard to reach or tricky to harvest often end up being more valuable. Some grow in dense forests, need careful digging, or have to be cleaned and prepared before use.

Matsutake mushrooms are a good example, because they grow in specific forest conditions and are hard to spot under layers of leaf litter. Wild ginger and black walnuts, meanwhile, both require extra steps for cleaning and preparation before they can be used or sold.

All of that takes time, effort, and experience. When something takes real work to gather safely, buyers are usually willing to pay more for it.

Foods That Keep Well Are More Valuable to Buyers

Some forageables, like dried morels or elderberries, can be stored for months without losing their value. These longer-lasting items are easier to sell and often bring in more money over time.

Others, like wild greens or edible flowers, have a short shelf life and need to be used quickly. Many easy-to-identify wild greens and herbs are best when fresh, but can be dried or preserved to extend their usefulness.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

When you’re foraging for high-value plants, mushrooms, or other wild ingredients, every decision matters. Whether you’re selling at a farmers market or stocking your own pantry, simple mistakes can make your harvest less valuable or even completely worthless.

Harvesting at the Wrong Time

Harvesting at the wrong time can turn a valuable find into something no one wants. Plants and mushrooms have a short window when they’re at their best, and missing it means losing quality.

Morels, for example, shrink and dry out quickly once they mature, which lowers their weight and price. Overripe berries bruise in the basket and spoil fast, making them hard to store or sell.

Improper Handling After Harvest

Rough handling can ruin even the most valuable forageables. Crushed mushrooms, wilted greens, and dirty roots lose both their appeal and their price.

Use baskets or mesh bags to keep things from getting smashed and let air circulate. Keeping everything cool and clean helps your harvest stay fresh and look better for longer.

This is especially important for delicate items like wild roots and tubers that need to stay clean and intact.

Skipping Processing Steps

Skipping basic processing steps can cost you money. A raw harvest may look messy, spoil faster, or be harder to use.

For example, chaga is much more valuable when dried and cut properly. Herbs like wild mint or nettle often sell better when bundled neatly or partially dried. If you skip these steps, you may end up with something that looks unappealing or spoils quickly.

Collecting from the Wrong Area

Harvesting in the wrong place can ruin a good find. Plants and mushrooms pulled from roadsides or polluted ground may be unsafe, no matter how fresh they look.

Buyers want to know their food comes from clean, responsible sources. If a spot is known for overharvesting or damage, it can make the whole batch less appealing.

These suburbia foraging tips can help you find overlooked spots that are surprisingly safe and productive.

Not Knowing the Market

A rare plant isn’t valuable if nobody wants to buy it. If you gather in-demand species like wild ramps or black trumpets, you’re more likely to make a profit. Pay attention to what chefs, herbalists, or vendors are actually looking for.

Foraging with no plan leads to wasted effort and unsold stock. Keeping up with demand helps you bring home a profit instead of a pile of leftovers.

You can also brush up on foraging for survival strategies to identify the most versatile and useful wild foods.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

Some of the most sought-after wild plants and fungi here can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re foraging for profit or personal use, these are the ones worth paying attention to:

Seaside Plantain (Plantago maritima)

The fleshy, narrow leaves of seaside plantain peek out from coastal rocks and salt marshes around the world. This hardy plant thrives where few others can, tolerating regular saltwater spray that would kill most vegetation. Its small, green flower spikes rise above the leaves on thin stalks.

You can identify seaside plantain by its thick, linear leaves forming a rosette at the base. Unlike the toxic death camas, it has no bulb underneath and always grows in salty environments.

Young leaves taste mildly salty with a pleasant crunch and can be eaten raw in salads or cooked like spinach. Only harvest the tender new growth for the best flavor.

Coastal people have relied on this plant for centuries as a vitamin C-rich food source. Its high mineral content makes it especially valuable during times when fresh vegetables are scarce. Foragers prize it for both nutrition and its unique taste of the sea.

Common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)

Persimmon, sometimes called American persimmon or common persimmon, grows as a small tree with rough, blocky bark and oval-shaped leaves. The fruit looks like a small, flattened tomato and turns a deep orange or reddish color when ripe.

If you bite into an unripe persimmon, you will quickly notice an extremely astringent, mouth-drying effect. A ripe persimmon, on the other hand, tastes sweet, rich, and custard-like, with a soft and jelly-like texture inside.

You can eat persimmons fresh once they are fully ripe, or you can cook them down into puddings, jams, and baked goods. Some people also mash and freeze the pulp to use later for pies, breads, and sauces.

Wild persimmons can sometimes be confused with black nightshade berries, but nightshade fruits are much smaller, grow in clusters, and stay dark purple or black. Only the ripe fruit of the persimmon tree should be eaten; the seeds and the unripe fruit are not edible.

Hen of the Woods (Grifola frondosa)

Oak trees often hide a treasure at their base – the magnificent hen of the woods mushroom. This fungal marvel creates large, ruffled clusters that truly resemble a fluffed-up hen sitting among the forest floor. A single cluster can weigh up to 40 pounds when fully grown!

The meaty texture and rich, earthy flavor make this mushroom perfect for vegetarian dishes. It holds up well in cooking, absorbing flavors while maintaining its satisfying bite.

Every part except the tough base where it attaches to the tree is edible. Look for its distinctive layered structure and grayish-brown color when hunting in the woods.

Few dangerous mushrooms look similar to hen of the woods. Berkeley’s polypore resembles it but has larger pores and a different texture. Returning to the same oak tree year after year often rewards foragers with fresh growth, making this mushroom a reliable wild food source.

Sea Lettuce (Ulva lactuca)

Underwater forests of bright green, paper-thin sea lettuce wave gently in coastal tides worldwide. This remarkable seaweed can either attach to rocks or float freely, creating vibrant patches visible from shore. It feels silky smooth when touched underwater.

Clean water is essential when harvesting sea lettuce, as it can absorb pollutants. Always collect from pristine areas and rinse thoroughly with fresh water before eating.

The nutritional profile of sea lettuce impresses even health experts. It contains high levels of iron, calcium, and vitamins A, B, and C – more than many land vegetables. This makes it valuable for foragers seeking wild superfoods.

The mild, slightly salty taste works well raw in salads, dried as a seasoning, or added to soups. There are virtually no dangerous look-alikes, making sea lettuce an excellent choice for beginning seaweed foragers who are just learning marine plants.

Spicebush berries (Lindera benzoin)

Spicebush has smooth-edged leaves that release a spicy citrus scent when crushed, and it produces clusters of red berries that grow close to the stem. Those berries, along with the young twigs and leaves, are all edible and flavorful.

The berries are especially valued for their warm, peppery kick and are often dried and ground as a seasoning. You can steep the leaves and twigs into tea or simmer them into broths.

Avoid confusing it with lookalikes like Carolina allspice, which has larger, thicker leaves and lacks the same aromatic quality. Its berries also differ in size and internal seed structure.

Spicebush has a long history of use in traditional cooking for its mild numbing effect and warming flavor. Only the berries, leaves, and tender twigs should be consumed—avoid the bark and roots.

Wild ramps (Allium tricoccum)

Known as wild ramp, leek, or ramson, this flavorful plant is famous for its broad green leaves and slender white stems. It grows low to the ground and gives off a strong onion-like scent when bruised, which can help you tell it apart from toxic lookalikes like lily of the valley.

If you give it a taste, you will notice a bold mix of onion and garlic flavors, with a tender texture that softens even more when cooked. People often sauté the leaves and stems, pickle the bulbs, or blend them into pestos and soups.

The entire plant can be used for cooking, but the leaves and bulbs are the most prized parts. It is important not to confuse it with similar-looking plants that do not have the signature onion smell when crushed.

Wild leek populations have declined in some areas because of overharvesting, so it is a good idea to only take a few from any given patch. When harvested thoughtfully, these vibrant greens can add a punch of flavor to just about anything you make.

Black walnuts (Juglans nigra)

The nuts of the black walnut, sometimes called American walnut or eastern black walnut, have a tough outer husk and a deeply ridged shell inside. When you crack them open, you will find a rich, oily seed with an earthy, slightly bitter flavor that sets them apart from the sweeter English walnut.

It is easy to confuse black walnut with butternut, another tree with compound leaves and rough bark. If you check the nuts closely, black walnut fruits are round with a thick green husk, while butternuts are more oval and sticky.

When you get your hands on the nuts, the common ways to prepare them include baking them into cookies, sprinkling them over salads, or grinding them into a strong-tasting flour. The seeds themselves have a firm, almost chewy texture when raw and become crunchy after roasting.

Only the inner seed is eaten, while the outer husk and shell are discarded because they contain compounds that can irritate your skin. A fun fact about this plant is that even the roots and leaves produce a chemical called juglone, which can make it hard for other plants to grow nearby.

American hazelnuts (Corylus americana)

Clusters of round, fringed husks tucked among bushy green leaves usually mean you have found American hazelnut, sometimes called American filbert. It grows as a wide, shrubby plant that spreads along forest edges, open woods, and overgrown fields.

The nuts inside are rich and buttery, with a firm texture that turns creamy when roasted or ground into flour. You can eat them raw, toss them into baked goods, or crush them into a thick, flavorful spread.

It helps to know the difference between American hazelnut and its close cousin, beaked hazelnut, which hides its nut inside a long, pointed husk. Both plants are safe to eat, but the shape of the husk makes it easy to tell which one you have.

Only the inner nut is gathered for food; the leafy husk and hard outer shell are tossed aside. If you leave them too long, local wildlife like squirrels will clear out the patch faster than you can.

Autumn olive berries (Elaeagnus umbellata)

With its silver-dusted leaves and small, speckled red fruits, autumn olive—also called silverberry or Japanese silverberry—has made its way into many thickets and field edges. The fruit is edible, tart, and slick-skinned, with a burst of sourness that mellows in cooked preparations.

People often turn autumn olive into jelly, sauces, or fermented beverages to tame the intense flavor. You can also dehydrate the berries into a powder for use in baked goods.

Some confuse it with Russian olive, which grows similar leaves but bears dry, yellow fruit instead. Stick to harvesting just the berries, as the rest of the plant doesn’t have any culinary use.

What makes autumn olive particularly interesting is its nitrogen-fixing ability, which helps it thrive where other plants struggle—but that same trait is also why it spreads so aggressively. Still, the fruit is safe and edible, and one of the few wild berries with such a high lycopene content.

Chanterelle Mushrooms (Cantharellus cibarius)

The forest floor transforms after summer rains when golden chanterelle mushrooms emerge like tiny trumpets pushing through the soil. Their distinct apricot-like fragrance fills the air, guiding experienced foragers to these culinary treasures hidden among fallen leaves.

Chanterelles form special relationships with tree roots, particularly oaks and conifers. This connection makes them impossible to farm commercially, increasing their value to mushroom hunters.

The entire mushroom is edible, with a delicate, fruity flavor unlike any store-bought variety. Their firm texture holds up well during cooking, making them popular in gourmet dishes.

Identifying true chanterelles requires checking for blunt ridges running down the stem instead of sharp gills. The dangerous look-alike jack-o-lantern mushroom grows on wood rather than soil and has true gills. Another impostor, the false chanterelle, lacks the distinctive fruity smell and has sharper gill-like structures.

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba)

The pawpaw grows fruits that are green and shaped a little like small mangoes. Inside, the soft yellow flesh tastes like a blend of banana, mango, and melon, with a custard-like texture that melts in your mouth.

If you are comparing it to similar plants, keep in mind that young pawpaw trees can look a little like young magnolias because of their large leaves. True pawpaws grow fruits with large brown seeds tucked inside, while magnolias do not produce anything that looks or tastes similar.

You can eat the flesh straight out of the skin with a spoon, or mash it into puddings, smoothies, and even homemade ice cream. Some people also like to freeze it into cubes for later, although it does tend to brown quickly once exposed to air.

Stick to eating the soft inner flesh. Make sure not to ingest the skin and seeds of the fruit because they contain compounds that can upset your stomach.

This fruit is that it was a favorite snack of Native Americans and early explorers long before it started showing up in backyard gardens.

Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina)

The edible part of staghorn sumac is the hairy, red fruit cluster that forms a cone shape at the tip of its branches. These clusters are packed with malic acid, giving them a tart flavor that’s perfect for making infused drinks.

Some people confuse it with poison sumac, but poison sumac has drooping white berries and lacks the fuzzy stems of staghorn sumac. That visual difference is critical when deciding what’s safe to forage.

After soaking the berry clusters in water, strain the result through a cloth or coffee filter to remove the irritating surface hairs. The liquid has a lemony bite that pairs well with honey or mint.

You can also dry the clusters and grind them into a reddish powder used like sumac spice in Middle Eastern dishes. Stick to the fruit only—none of the other parts are edible.

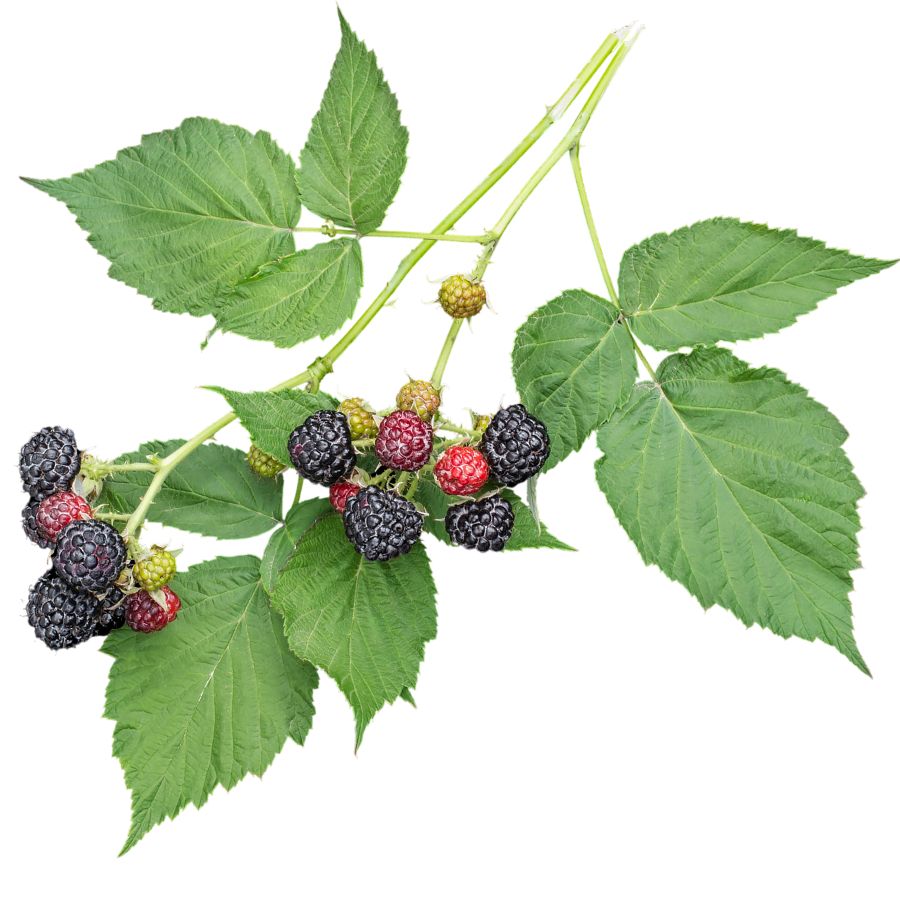

Wild black raspberries (Rubus occidentalis)

Black raspberries grow on arching canes covered with small, hooked thorns. The berries start out red before ripening to a deep purplish-black color, and they have a hollow core when picked.

The fruit tastes sweet with a mild tartness, and the texture is juicy but slightly firmer than a red raspberry. People often use black raspberries for jams, pies, syrups, and even simple fruit leathers made at home.

Blackberry and wineberry are common lookalikes, which can confuse foragers at first glance. Black raspberry canes usually have a whitish coating and smaller thorns compared to the shinier, stouter canes of a blackberry.

You can eat the ripe fruit raw or cooked, but the leaves are sometimes brewed into teas after proper drying. It is best to avoid the green, unripe berries, as they are tough and lack the flavor that makes black raspberry such a favorite.

Shaggy Mane Mushrooms (Coprinus comatus)

Unlike most wild mushrooms that hide in forests, the distinctive shaggy mane proudly stands tall in urban parks, lawns, and roadside areas. These white, cylinder-shaped mushrooms covered in upturned scales look like something from a fairy tale, often appearing suddenly after rainfall.

Time is critical when harvesting shaggy manes. Within hours of maturing, they begin a fascinating self-digestion process, turning their caps into black ink. Ancient people actually used this ink for writing!

Only collect shaggy manes with white or pink gills – once they begin turning black, the flavor becomes unpleasant. The caps are prized for their mild, nutty taste, while most foragers discard the stringy stems.

Beginning mushroom hunters appreciate shaggy manes because they have few dangerous look-alikes. The similar alcohol inky cap is smaller and can cause unpleasant reactions when eaten with alcoholic drinks.

Look for shaggy manes in disturbed soil areas, especially after rain, for a safe and delicious wild mushroom experience.

Glasswort (Sarcocornia perennis)

Resembling miniature cacti without spines, glasswort stands out along coastal salt marshes with its segmented, bright green succulent stems that grow in small bushy clumps.

This unusual plant turns striking red or purple in autumn, creating colorful patches in otherwise muted marsh landscapes.

The crunchy, juicy stems have a naturally salty flavor that needs no additional seasoning. When cooked, glasswort maintains its bright color but softens pleasantly. The entire above-ground portion is edible and can be enjoyed raw in salads or lightly steamed as a vegetable.

There are no toxic look-alikes for glasswort, making it safe for beginner foragers. However, only collect from clean waters, as this plant can absorb pollutants from its environment. Its high mineral content and unique texture make it both nutritious and interesting in wild food dishes.

Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus)

Jerusalem artichoke grows tall with sunflower-like blooms and has knobby underground tubers. The tubers are tan or reddish and look a bit like ginger root, though they belong to the sunflower family.

The part you’re after is the tuber, which has a nutty, slightly sweet flavor and a crisp texture when raw. You can roast, sauté, boil, or mash them like potatoes, and they hold their shape well in soups and stir-fries.

Some people experience gas or bloating after eating sunchokes due to the inulin they contain, so it’s a good idea to try a small amount first. Cooking them thoroughly can help reduce the chances of digestive discomfort.

Sunchokes don’t have many dangerous lookalikes, but it’s important not to confuse the plant with other sunflower relatives that don’t produce tubers. The above-ground part resembles a small sunflower, but it’s the knotted, underground tubers that are worth digging up.

Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

Some parts of the state are better than others when it comes to finding valuable wild plants and mushrooms. Here are the different places where you’re most likely to have luck:

| Plant | Locations |

|---|---|

| Seaside plantain (Plantago maritima) | – Prime Hook Beach marshes – Port Mahon shoreline – Pickering Beach dunes |

| Common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | – Middle Run Valley Natural Area – Blackbird State Forest – White Clay Creek Preserve |

| Hen of the woods (Grifola frondosa) | – Burton Island Nature Preserve – Lums Pond woods – Auburn Valley Trail |

| Sea lettuce (Ulva lactuca) | – Holts Landing State Park coast – Rehoboth Bay shallows – Little Assawoman Bay edge |

| Spicebush berries (Lindera benzoin) | – Brandywine Creek State Park – Papermill Park wooded trails – Glasgow Park forests |

| Wild ramps (Allium tricoccum) | – White Clay Creek State Park (non-federal areas) – Coverdale Farm Preserve – Judge Morris Estate woods |

| Black walnuts (Juglans nigra) | – Silver Lake Park (Dover) – Big Oak County Park – Milford Millponds Nature Preserve |

| American hazelnuts (Corylus americana) | – Fork Branch Nature Preserve – Coverdale Woods – Carousel Farm Park |

| Autumn olive berries (Elaeagnus umbellata) | – Delcastle Recreation Area – Bellevue State Park edges – Alapocas Run greenway |

| Chanterelle mushrooms (Cantharellus cibarius) | – Middleford North Woods – Redden Forest – Ashland Nature Center trails |

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | – Woodland Beach Wildlife Area – Rockwood Park – Iron Hill Park ravines |

| Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina) | – Cape Henlopen roadside trails – Banning Park outskirts – Smyrna River Greenway |

| Wild black raspberries (Rubus occidentalis) | – Blackbird Creek Reserve – Yorklyn Bridge Trail – Kenton Woodland Park |

| Shaggy mane mushrooms (Coprinus comatus) | – Tidbury Creek Park – Baynard Stadium field edge – Hudson Park (Milford) |

| Glasswort (Sarcocornia perennis) | – Slaughter Beach flats – Mispillion Harbor – Lewes salt marshes |

| Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | – Hunn Nature Park – Broadkill River Trail – Phillips Landing Riverwalk |

When to Forage for Maximum Value

Every valuable wild plant or mushroom has its season. Here’s a look at the best times for harvest:

| Plants | Valuable Parts | Best Harvest Season |

|---|---|---|

| Seaside plantain (Plantago maritima) | Young leaves | May – August |

| Common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | Ripe fruits | September – November |

| Hen of the woods (Grifola frondosa) | Fruiting body (mushroom) | September – November |

| Sea lettuce (Ulva lactuca) | Leafy thallus (seaweed fronds) | April – August |

| Spicebush berries (Lindera benzoin) | Berries (fruits), young leaves | Leaves: May – June, Berries: August – September |

| Wild ramps (Allium tricoccum) | Bulbs, young leaves | April – May |

| Black walnuts (Juglans nigra) | Nuts (inner kernel) | September – October |

| American hazelnuts (Corylus americana) | Nuts | August – September |

| Autumn olive berries (Elaeagnus umbellata) | Ripe berries | September – October |

| Chanterelle mushrooms (Cantharellus cibarius) | Fruiting body (mushroom) | July – September |

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | Ripe fruits | August – October |

| Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina) | Berry clusters (drupes) | July – September |

| Wild black raspberries (Rubus occidentalis) | Ripe berries | June – July |

| Shaggy mane mushrooms (Coprinus comatus) | Fruiting body (mushroom) | September – November |

| Glasswort (Sarcocornia perennis) | Young succulent stems | July – September |

| Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | Underground tubers | October – November |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.