Across Alabama’s fields, forests, and creekbanks, there’s an incredible range of wild edible plants waiting to be found. Black walnuts drop in abundance once the husks crack open, and goldenrod shoots up along fence lines in late summer, drawing pollinators and foragers alike.

A few careful steps through the right stretch of woods might even bring you face-to-face with a flush of lion’s mane mushrooms growing from a decaying log!

Some of the most useful forageables don’t shout for attention. American plums blend into hedgerows, offering tart fruit that turns sweet as it ripens, and maypop vines can sprawl unnoticed until their exotic-looking flowers appear.

Whether you’re after fruits, nuts, greens, or roots, Alabama delivers options in every season. The more you learn, the more you realize how much you’ve been walking past without noticing. With the right knowledge, you can bring home an impressive mix of wild edibles from even a short foraging trip.

What We Cover In This Article:

- What Makes Foreageables Valuable

- Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

- The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

- Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

- When to Forage for Maximum Value

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

What Makes Foreageables Valuable

Some wild plants, mushrooms, and natural ingredients can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re selling them or using them at home, their worth often comes down to a few key things:

The Scarcer the Plant, the Higher the Demand

Some valuable forageables only show up for a short time each year, grow in hard-to-reach areas, or are very difficult to cultivate. That kind of rarity makes them harder to find and more expensive to buy.

Morels, truffles, and ramps are all good examples of this. They’re popular, but limited access and short growing seasons mean people are often willing to pay more.

A good seasonal foods guide can help you keep track of when high-value items appear.

High-End Dishes Boost the Value of Ingredients

Wild ingredients that are hard to find in stores often catch the attention of chefs and home cooks. When something unique adds flavor or flair to a dish, it quickly becomes more valuable.

Truffles, wild leeks, and edible flowers are prized for how they taste and look on a plate. As more people try to include them in special meals, the demand—and the price—tends to rise.

You’ll find many of these among easy-to-identify wild mushrooms or herbs featured in fine dining.

Medicinal and Practical Uses Drive Forageable Prices Up

Plants like ginseng, goldenseal, and elderberries are often used in teas, tinctures, and home remedies. Their value comes from how they support wellness and are used repeatedly over time.

These plants are not just ingredients for cooking. Because people turn to them for ongoing use, the demand stays steady and the price stays high.

The More Work It Takes to Harvest, the More It’s Worth

Forageables that are hard to reach or tricky to harvest often end up being more valuable. Some grow in dense forests, need careful digging, or have to be cleaned and prepared before use.

Matsutake mushrooms are a good example, because they grow in specific forest conditions and are hard to spot under layers of leaf litter. Wild ginger and black walnuts, meanwhile, both require extra steps for cleaning and preparation before they can be used or sold.

All of that takes time, effort, and experience. When something takes real work to gather safely, buyers are usually willing to pay more for it.

Foods That Keep Well Are More Valuable to Buyers

Some forageables, like dried morels or elderberries, can be stored for months without losing their value. These longer-lasting items are easier to sell and often bring in more money over time.

Others, like wild greens or edible flowers, have a short shelf life and need to be used quickly. Many easy-to-identify wild greens and herbs are best when fresh, but can be dried or preserved to extend their usefulness.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

Foraging Mistakes That Cost You Big Bucks

When you’re foraging for high-value plants, mushrooms, or other wild ingredients, every decision matters. Whether you’re selling at a farmers market or stocking your own pantry, simple mistakes can make your harvest less valuable or even completely worthless.

Harvesting at the Wrong Time

Harvesting at the wrong time can turn a valuable find into something no one wants. Plants and mushrooms have a short window when they’re at their best, and missing it means losing quality.

Morels, for example, shrink and dry out quickly once they mature, which lowers their weight and price. Overripe berries bruise in the basket and spoil fast, making them hard to store or sell.

Improper Handling After Harvest

Rough handling can ruin even the most valuable forageables. Crushed mushrooms, wilted greens, and dirty roots lose both their appeal and their price.

Use baskets or mesh bags to keep things from getting smashed and let air circulate. Keeping everything cool and clean helps your harvest stay fresh and look better for longer.

This is especially important for delicate items like wild roots and tubers that need to stay clean and intact.

Skipping Processing Steps

Skipping basic processing steps can cost you money. A raw harvest may look messy, spoil faster, or be harder to use.

For example, chaga is much more valuable when dried and cut properly. Herbs like wild mint or nettle often sell better when bundled neatly or partially dried. If you skip these steps, you may end up with something that looks unappealing or spoils quickly.

Collecting from the Wrong Area

Harvesting in the wrong place can ruin a good find. Plants and mushrooms pulled from roadsides or polluted ground may be unsafe, no matter how fresh they look.

Buyers want to know their food comes from clean, responsible sources. If a spot is known for overharvesting or damage, it can make the whole batch less appealing.

These suburbia foraging tips can help you find overlooked spots that are surprisingly safe and productive.

Not Knowing the Market

A rare plant isn’t valuable if nobody wants to buy it. If you gather in-demand species like wild ramps or black trumpets, you’re more likely to make a profit. Pay attention to what chefs, herbalists, or vendors are actually looking for.

Foraging with no plan leads to wasted effort and unsold stock. Keeping up with demand helps you bring home a profit instead of a pile of leftovers.

You can also brush up on foraging for survival strategies to identify the most versatile and useful wild foods.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

The Most Valuable Forageables in the State

Some of the most sought-after wild plants and fungi here can be surprisingly valuable. Whether you’re foraging for profit or personal use, these are the ones worth paying attention to:

American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)

Persimmon fruit has a round shape and orange skin, usually with a slightly pointed end and a leafy cap still attached. It’s easy to bite into a ripe one and find it meltingly soft, with a flavor that’s both sugary and floral.

People sometimes confuse it with wild tomato-like fruits, but persimmons grow on hardwood trees and the fruit has a firmer skin. Avoid eating them when firm and unripe, as they contain tannins that cause a strong puckering sensation.

The pulp is the part most commonly used, and it’s great in baked goods or even frozen into a simple sorbet. Some cooks mash it into jam or dehydrate slices for a chewy snack.

Wild persimmons are valuable more for their flavor than for any consistent market price, though foragers and specialty sellers often get a few dollars per pound. The rich taste and the tree’s ability to grow in various soils make this fruit worth the effort to find.

Goldenrod (Solidago spp.)

If you’ve ever noticed a cluster of tall plants with small yellow flower tufts along the stem, you were probably looking at goldenrod, also called woundwort or blue mountain tea. It has narrow lance-shaped leaves and grows in dense bunches that can easily be mistaken for ragweed, but ragweed has greenish flowers and a more feathery appearance.

The flowers and young leaves of goldenrod are edible and can be used to make tea with a mildly sweet, slightly bitter flavor and a smooth, soothing texture. Older leaves tend to be too tough and fibrous for consumption.

People usually dry the flowering tops for storage, using them later in infusions or blended with other herbs. When fresh, they can also be steeped directly, though the flavor becomes stronger and a little more bitter with age.

Goldenrod can often be sold in herbal markets in dried form for a few dollars per ounce. Its value mainly comes from how easy it is to preserve and combine with other ingredients.

Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis)

For centuries, elderberries have been gathered not just for food, but for making home remedies prized across the Southwest. Also called Mexican elder and tapiro, elderberry grows as a sprawling bush or small tree with clusters of tiny white flowers that turn into dusty blue-black berries.

There are toxic lookalikes you need to watch for, especially red elderberry, which has round clusters of bright red fruit. Elderberries grow in flatter, broader clusters and have a softer, more powdery appearance when ripe.

The berries have a deep, earthy flavor with a tart edge, and are usually cooked into jams, syrups, and baked goods to bring out their richness.

Make sure to avoid eating the raw berries, seeds, bark, or leaves because they can cause nausea unless they are properly cooked.

This plant stays valuable because the berries are used heavily in teas, tinctures, and syrups that people rely on for wellness, driving steady demand. Elderberries can also be dried and stored for months, making it even more profitable compared to foods that spoil quickly.

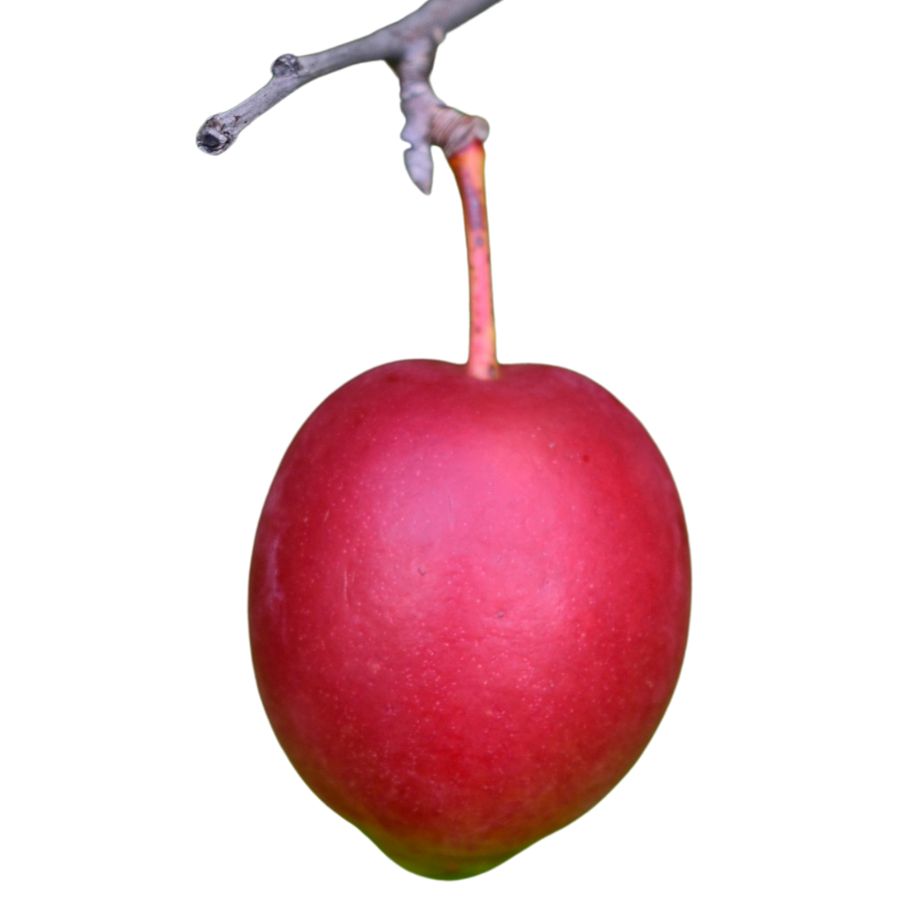

American Plum (Prunus americana)

American plums grow on small trees and produce fruit that ranges from deep red to bluish-purple with a waxy coating. The skin is tart and a little astringent, but the flesh inside is sweet, soft, and juicy when fully ripe.

You can eat the fruit fresh, but it’s more often cooked down into jelly, jam, or syrup. The pits are not edible and should always be discarded.

Some cherry species grow in similar clusters, but cherries tend to be smaller, rounder, and darker with smoother bark. American plum leaves also have a rough texture that helps separate them from other lookalikes.

These plums are valuable in small markets, especially when turned into preserves or wine. Individual trees can yield a good harvest, but the fruit is delicate and doesn’t store long.

Maypop (Passiflora incarnata)

The maypop is a fast-growing vine with climbing tendrils, lobed leaves, and large purple-and-white flowers that turn into egg-shaped fruits. The fruit is the edible part, filled with a soft, pulpy interior that’s sweet, tart, and packed with crunchy black seeds.

People often eat the pulp raw or strain it into drinks, jellies, or syrups for its tropical flavor and smooth texture. It’s important not to eat the outer rind or the green, unripe fruit, which can cause digestive issues.

Maypop is sometimes mistaken for other passionflowers that don’t produce edible fruit, but the edible type has a round, wrinkly skin when ripe and a strong fruity scent. The leaves and roots aren’t used for food and shouldn’t be consumed.

Fresh maypops can sell for a few dollars each at specialty markets, especially in areas where they aren’t widely cultivated. Because the fruit doesn’t store well, its value comes from freshness and the effort it takes to collect it before it spoils.

Muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia)

Muscadine grows as a vigorous vine and produces thick-skinned grapes with a bold, aromatic flavor. The edible part is the inner pulp, which is often pressed for juice or cooked into jams and jellies.

The skin is edible but extremely chewy, and the seeds are large and best removed if you’re cooking with them. Fresh muscadines are sweet, with a strong taste that leans toward earthy or floral depending on ripeness.

Moonseed is a lookalike vine that can be deadly if mistaken for muscadine—its single seed and lack of tendrils are good clues to tell them apart. True muscadines also have tendrils and multiple seeds per fruit, and their taste is distinctly sweet rather than bitter.

While the leaves and green fruit shouldn’t be eaten, ripe muscadine grapes are highly sought after for winemaking and preserve-making. Homemade muscadine wine and jam can sell for a premium due to the fruit’s strong flavor and limited regional availability.

Black Walnut (Juglans nigra)

Black walnut grows a nut that’s prized for its strong, musky flavor and crunchy texture. The inner shell is extremely hard and often needs to be cracked with a vise or hammer to reach the oily, wrinkled seed inside.

Its nuts are most often roasted, chopped into desserts, or used in meat rubs and dressings. They’re also one of the few foraged tree nuts that can be stored long-term with very little processing.

The outer green husks leave a dark stain when bruised or broken open, and the nut itself is hidden inside a thick shell. While the fruit of the tree may resemble buckeye at first glance, black walnut leaves have a different shape and pattern, and buckeye seeds are toxic.

Prices stay high because harvesting takes time and experience, and the trees don’t lend themselves easily to large-scale production. Foragers and specialty food makers often pay a premium for wild black walnuts with intense flavor.

Wild Garlic (Allium vineale)

When you come across wild garlic, you’ll notice it by its slender, hollow leaves and the strong onion-like scent it gives off when crushed. Its bulbs and leaves are edible, with a flavor that’s sharper than cultivated garlic.

One important thing to watch out for is the resemblance to some toxic lookalikes, like death camas, which lacks the distinctive garlic smell. Always crush a leaf before collecting to check for that unmistakable odor.

In the kitchen, wild garlic is often used fresh in pestos or sautés, and the bulbs can be pickled or roasted. The leaves have a tender texture and a pungent bite, making them useful in any dish that benefits from a punch of garlic flavor.

Wild garlic has limited market value because it’s considered invasive in many regions. Still, it holds practical value for foragers who want a fresh, wild seasoning right from the ground.

Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva)

The daylily is a bright orange flower with long, sword-shaped leaves that grows in clumps and sends up tall flowering stalks. It looks similar to some toxic lilies, but true daylilies have thick, fleshy roots and grow multiple flowers from a single stalk.

You can eat the buds, flowers, young shoots, and tuber-like roots, but the buds and flowers are the most commonly used. The petals have a crisp, slightly sweet flavor when raw, and they’re often stir-fried or added to soups.

Some people experience digestive issues from eating large amounts of raw daylily, so it’s best to try a small portion first. Avoid confusing it with similar-looking lilies like tiger lily or Easter lily, which are not safe to eat.

The flowers are sometimes sold dried in Asian markets and used in traditional dishes, giving them modest value in the specialty food world. Because several parts of the plant are edible and have distinct culinary uses, it’s a popular foraged food.

Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus)

Lion’s mane mushrooms grow in white, shaggy clusters that hang like icicles from hardwood trees. The entire fruiting body is edible and has a soft, meaty texture that’s often compared to crab or lobster.

People value lion’s mane not just for the flavor but for how well it soaks up sauces in stir-fries, soups, or even pan-seared dishes. It’s usually sliced and cooked fresh, though it can be dried and rehydrated without losing much texture.

While it doesn’t have many dangerous lookalikes, some species of toothed fungi like bear’s head or comb tooth can resemble it. Those are also edible, but if a mushroom is discolored, mushy, or growing from the ground instead of wood, skip it.

Fresh lion’s mane sells for a high price at gourmet markets and restaurants because of its short shelf life and culinary demand. Its chewy bite and slightly sweet, nutty taste make it a favorite among chefs and home cooks alike.

Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album)

Lamb’s quarters, or wild spinach, is a common backyard plant with diamond-shaped leaves that often look like they’ve been dusted with flour. That powdery texture is one of the simplest ways to tell it apart from toxic plants that have smoother or glossier leaves.

The younger leaves have a mild taste and soft texture, making them popular in stir-fries and pestos. Most people harvest the leaves and tender tops, but the tiny seeds are also usable if properly prepared.

Some plants that resemble lamb’s quarters, like young pokeweed, are not safe to eat and have very different stem coloration. Lamb’s quarters typically has green to purplish stems and no berries.

Because of how nutritious and versatile it is, the plant has been gathered for centuries across many cultures. It’s not a high-ticket item, but it does show up in specialty food markets and foraged meal boxes.

Spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

With their bright red color and clustered growth, spicebush berries are easy to pick out once you know the shrub’s distinctive lemon-scented leaves. Some people mix them up with winterberry, but winterberry lacks the spicy scent and has smooth-edged leaves instead of the alternate, veiny ones on spicebush.

The flavor is rich and complex, often described as a cross between black pepper, allspice, and citrus. Foragers usually dry the berries before using them in meat rubs, baked goods, or wildcrafted spice mixes.

Spicebush bark and leaves have traditional uses, but when it comes to edible parts, the berries are what people go after. They’re sometimes steeped whole in broths or ground into powder for stronger flavor.

Because they aren’t cultivated on a large scale, spicebush berries carry a higher value among foragers and food artisans. A small amount can go a long way, especially in recipes that highlight wild-sourced ingredients.

Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius)

Golden chanterelles, also called egg mushrooms or girolles, are funnel-shaped and usually a bright yellow-orange with false gills that appear as deep, forked wrinkles. They have a fruity smell, almost like apricots, and a dense, meaty texture when cooked.

The part you want is the whole cap and stem, both of which soften nicely in butter or cream-based dishes. Their flavor is rich and peppery, which makes them popular in risottos, sautés, and soups.

A common lookalike is the jack-o’-lantern mushroom, which glows faintly in the dark and has true gills instead of shallow ridges. That one will give you stomach cramps, so pay close attention to the gill structure and color.

Fresh chanterelles can sell for over $20 per pound at farmers markets and restaurants, especially when demand is high. Their shelf life is short, but you can extend it by drying or pickling them soon after harvest.

Morel (Morchella esculenta)

Morel mushrooms have a honeycomb-like surface with deep pits and ridges. The cap is fully attached to the stem, which helps set them apart from dangerous lookalikes like false morels that often have wrinkled, lobed caps and loose or cottony interiors.

The rich, nutty flavor and slightly chewy texture make morels a favorite in high-end kitchens. Many people sauté them in butter, stuff them, or dry them for later use because they hold their flavor extremely well.

Always cook morels thoroughly because raw ones can cause stomach upset, even when they look perfectly normal.

Morels are highly prized by chefs and home cooks, sometimes selling for over $50 per pound fresh and even more when dried.

Part of what makes morels so valuable is how hard they are to cultivate and find. They often grow in specific, unpredictable places, and their short harvesting window drives up both the demand and the price.

Chufa (Cyperus esculentus)

Chufa, also called tiger nut or nut grass, grows in clumps of slender green blades with a cluster of small, wrinkled tubers hidden in the soil. These tubers are the edible part of the plant, often dug up, rinsed, and eaten raw or dried for later use.

The flavor of chufa is slightly sweet with a nutty, coconut-like aftertaste, and the texture is chewy when raw or crunchy when roasted. Many people grind it into flour or soak it for drinks.

Chufa is sometimes confused with similar sedges, but true tiger nut tubers are more fibrous and flavorful than lookalikes like yellow nutsedge. Make sure you’re harvesting from a clean site, as the tubers can absorb contaminants from the soil.

What makes chufa valuable is its nutritional density and long shelf life when dried. While not particularly expensive, its flour can fetch a decent price in specialty food markets.

Groundnut (Apios americana)

Groundnut grows as a vining plant with compound leaves and reddish-purple flowers, but the part you’re after is buried underground. Its tubers are edible, protein-rich, and surprisingly high in calories compared to most wild plants.

They can be peeled and boiled like potatoes, or slow-roasted to bring out a nutty, slightly sweet taste. Some people mash them or slice them thin to fry into chips.

It’s easy to confuse groundnut with trailing wild beans or other legumes, especially if you’re only looking at the vines. The key difference is the string of bead-like tubers that groundnut sends down into the soil.

These tubers have drawn attention from permaculture growers and chefs for their nutritional value and earthy flavor. While not mass-produced, they can sell for over $15 per pound in niche food markets.

Blackberry (Rubus allegheniensis)

Blackberries grow on arching canes with hooked thorns and have five-petaled white flowers that appear before the fruit. They’re often mistaken for dewberries, but dewberries ripen earlier and usually sit closer to the ground.

Only the fruit is considered edible, and it’s commonly used in pies, jellies, wines, or eaten by the handful. The taste is rich, sweet, and slightly tangy, with a satisfying soft pop when you bite into a ripe one.

Some foragers also use young leaves in teas, but they’re not eaten as food. Be careful when gathering, since the brambles can be dense and the thorns are sharp.

Blackberries are valuable in both local markets and home kitchens because of their versatility and flavor. Depending on the region and demand, foraged blackberries can fetch a decent price, especially when sold fresh.

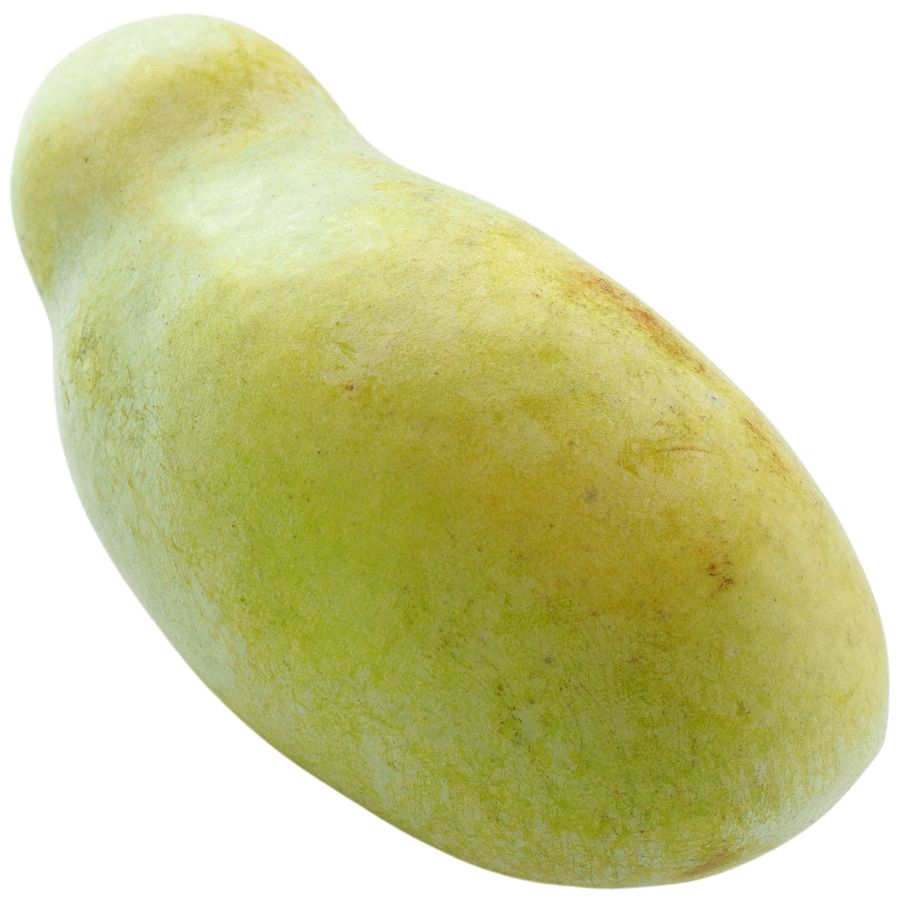

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba)

Pawpaw produces a green, mango-shaped fruit with soft yellow flesh inside and a taste that’s hard to forget. The flavor is rich and tropical, and the texture is thick like custard.

You’ll want to avoid the seeds and skin, but the pulp is edible and highly sought after. Some people cook it down into jams while others prefer it raw, straight from the peel.

There are other fruits in wooded areas that look similar, but pawpaw’s smell and size help separate it from anything potentially inedible. The way its fruits grow in clusters is also a giveaway.

Pawpaw isn’t commonly found in grocery stores, which makes it valuable for small growers and foragers. In-season, it can fetch a premium price at specialty food shops and farmers markets.

Where to Find Valuable Forageables in the State

Some parts of the state are better than others when it comes to finding valuable wild plants and mushrooms. Here are the different places where you’re most likely to have luck:

| Plant | Locations |

| American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | – Bankhead National Forest – Cheaha State Park – Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge |

| Goldenrod (Solidago spp.) | – William Bankhead National Forest – Monte Sano State Park – Gulf State Park |

| Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) | – Sipsey Wilderness – Oak Mountain State Park – Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge |

| American Plum (Prunus americana) | – Cahaba River National Wildlife Refuge – Conecuh National Forest – Rickwood Caverns State Park |

| Maypop (Passiflora incarnata) | – Oak Mountain State Park – Natchez Trace Parkway (AL section) – Tuskegee National Forest |

| Muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia) | – Talladega National Forest (Oakmulgee District) – Cheaha State Park – Black Warrior Wildlife Management Area |

| Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | – Bankhead National Forest – Conecuh National Forest – Monte Sano State Park |

| Wild Garlic (Allium vineale) | – Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge – Joe Wheeler State Park – Lake Guntersville State Park |

| Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) | – Gulf State Park – Cheaha State Park – Bankhead National Forest |

| Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus) | – Bankhead National Forest – Oak Mountain State Park – Talladega National Forest |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | – Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge – Oak Mountain State Park – Cahaba River National Wildlife Refuge |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | – Cahaba River National Wildlife Refuge – Oak Mountain State Park – Sipsey Wilderness |

| Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius) | – Bankhead National Forest – Cheaha State Park – Oak Mountain State Park |

| Morel (Morchella esculenta) | – Sipsey Wilderness – William B. Bankhead National Forest – Talladega National Forest |

| Chufa (Cyperus esculentus) | – Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge – Cahaba River National Wildlife Refuge – Joe Wheeler State Park |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | – Sipsey Wilderness – Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge – Oak Mountain State Park |

| Blackberry (Rubus allegheniensis) | – Bankhead National Forest – Oak Mountain State Park – Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge |

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | – Sipsey Wilderness – Oak Mountain State Park – Bankhead National Forest |

When to Forage for Maximum Value

Every valuable wild plant or mushroom has its season. Here’s a look at the best times for harvest:

| Plants | Valuable Parts | Best Harvest Season |

| American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | Ripe fruit | September – November |

| Goldenrod (Solidago spp.) | Flowers, young leaves | August – October |

| Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) | Berries, flowers | May – June (flowers), July – August (berries) |

| American Plum (Prunus americana) | Ripe fruit | June – August |

| Maypop (Passiflora incarnata) | Ripe fruit, flowers, leaves | July – October |

| Muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia) | Ripe fruit | August – October |

| Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | Nuts, husks | September – November |

| Wild Garlic (Allium vineale) | Bulbs, leaves | February – April |

| Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) | Flower buds, young shoots, tubers | March – June (shoots, tubers), May – July (buds) |

| Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus) | Fruiting body | September – November |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | Leaves, young stems, seeds | April – June (greens), August – September (seeds) |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | Leaves, berries, twigs | June – August (leaves), September – October (berries) |

| Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius) | Fruiting body | June – September |

| Morel (Morchella esculenta) | Fruiting body | March – April |

| Chufa (Cyperus esculentus) | Tubers | September – November |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | Tubers, seeds | September – November |

| Blackberry (Rubus allegheniensis) | Ripe fruit, young shoots | March – April (shoots), May – July (berries) |

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | Ripe fruit | August – October |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.