Massachusetts holds a rich history of silver mining, dating back to the 1600s. While silver mining in Massachusetts wasn’t as extensive as in other regions, there were indeed significant deposits discovered in areas like Worcester County.

Today, rockhounds still uncover impressive silver specimens throughout the State, particularly in the western regions where ancient volcanic activities left behind valuable mineral deposits.

We’ve gathered the most promising locations where you can find silver in Massachusetts.

These spots have been verified by local geology experts and experienced collectors, saving you countless hours of research and failed expeditions.

Whether you’re a beginner or a seasoned collector, these locations offer real opportunities to add silver specimens to your collection.

How Silver Forms Here

Silver forms when super-hot fluids, heated by magma deep underground, flow through cracks in rocks. These fluids, rich in minerals, carry dissolved silver along with other metals.

As these hot solutions cool down and move upward, they deposit silver in veins within the rock.

Often, silver combines with sulfur to create argentite, the most common silver ore. Sometimes, it mixes with other elements like chlorine or forms pure silver threads.

The process happens slowly, over millions of years, as these mineral-rich fluids repeatedly fill and crystallize in underground fractures. The best deposits usually form where there’s a lot of volcanic activity.

Types of Silver Found in the US

The US is home to many silver types, and our state boasts some noteworthy examples as well. Each type showcases its own unique beauty and intriguing characteristics, such as:

Native Silver Flakes

Native silver flakes display a stunning silvery-white color with a bright metallic shine. These thin, plate-like formations often show interesting branching patterns called dendritic structures.

The flakes can range from paper-thin to slightly thicker plates, each with its own unique pattern and formation.

These specimens are pure elemental silver, occurring naturally without combining with other elements. This purity gives them their characteristic bright, untarnished appearance when freshly exposed.

The formation process creates remarkable and intricate shapes resulting in each flake having a unique structure, some showing tree-like patterns while others form geometric shapes. The branching patterns are particularly fascinating, resembling miniature silver trees.

The flakes sometimes appear as overlapping layers, creating complex three-dimensional structures. These formations result from specific geological conditions where silver compounds were naturally reduced to pure silver.

Native silver flakes are highly sought after due to their purity and their unique structures. The more bizarre the formation—such as branching or twisted structures—the higher the value among collectors.

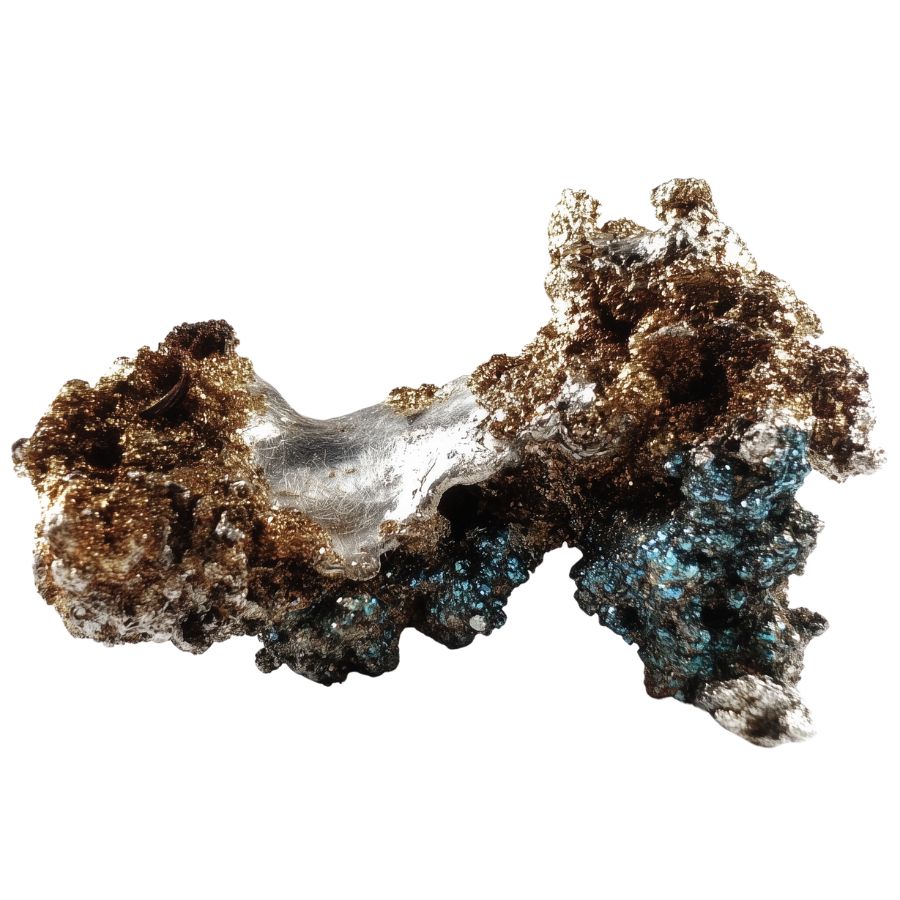

Native Silver Wires

Native silver wires present as delicate, hair-like strands that often curl and twist into fascinating formations. Fresh specimens show a brilliant silver color, though they may darken over time due to natural tarnishing.

The purity of these wires is remarkable, often exceeding 99.7% silver. Their structure shows unique growth patterns, with individual strands that can be incredibly long compared to their width. Some specimens show length-to-width ratios greater than 20, creating impressive specimens.

The internal structure of these wires reveals interesting features called twins – areas where the crystal structure changes direction.

This twinning creates unique patterns visible under magnification and contributes to the wire’s ability to bend and twist into various shapes.

These specimens often maintain their shape despite their delicate appearance. The natural formation process creates stronger structures than you might expect from such thin strands.

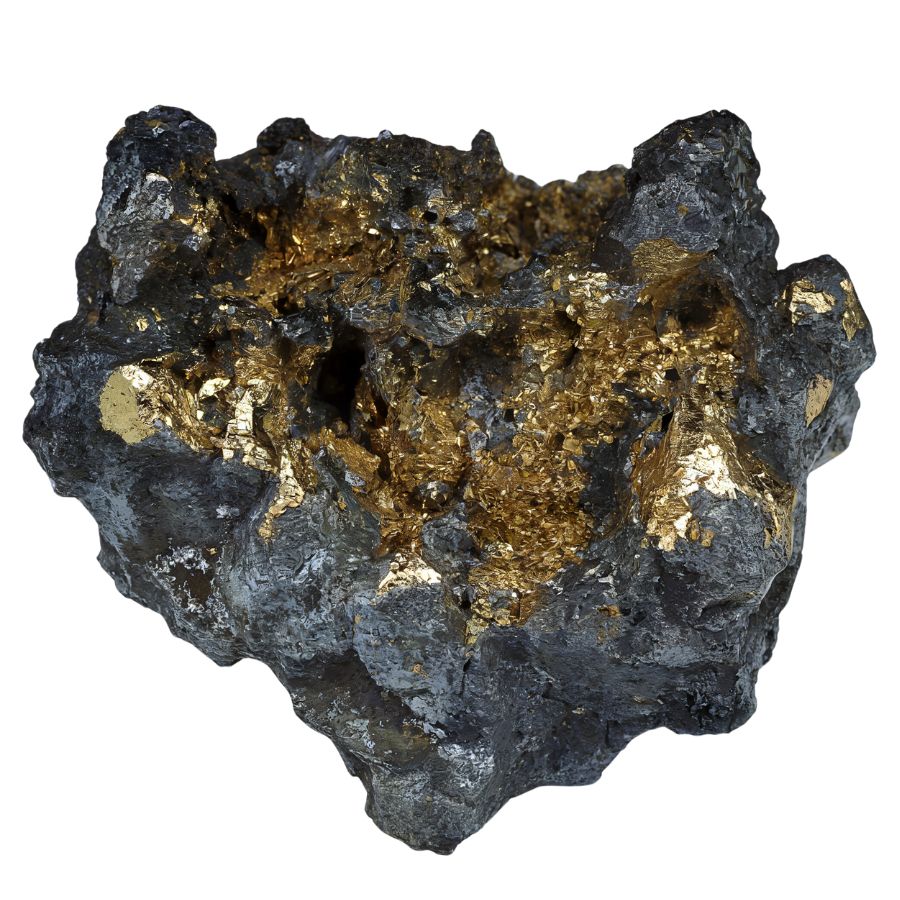

Galena

Galena showcases a striking lead-gray color with a brilliant metallic shine when freshly exposed. Its surface can develop a duller appearance over time, creating an interesting aging effect.

The crystal structure forms perfect cubes and eight-sided shapes called octahedra, making it easily recognizable.

One of the most fascinating aspects of galena is its weight. It feels surprisingly heavy in hand compared to other minerals of similar size. This high density comes from its rich lead content, which also makes it the primary source of lead worldwide.

Galena played a crucial role in early wireless communication. Its natural semiconductor properties made it an essential component in crystal radio receivers.

Ancient civilizations recognized its value as early as 3000 BC, using it for various metallurgical purposes.

SAFETY WARNING: Handling Galena requires extreme caution. It has high lead content that makes it toxic if ingested or inhaled. Always wash hands after handling, wear gloves, and never lick or taste the mineral.

Chlorargyrite

Chlorargyrite displays an intriguing pearly gray to brown color, often forming cube-shaped crystals. Its surface shows a unique silky to resinous shine, setting it apart visually. The mineral frequently appears as crusts or coatings, creating interesting surface patterns.

Perhaps the most captivating feature of chlorargyrite is its response to light. When exposed to sunlight, it undergoes a remarkable transformation, changing color to various shades of gray or purple. This happens as the mineral breaks down into pure silver, demonstrating a fascinating natural process.

The formation of chlorargyrite involves an interesting geological process called supergene enrichment. This occurs when metals dissolve from their original minerals and concentrate in new locations, creating pure deposits of chlorargyrite.

This mineral’s light sensitivity made it valuable in the early days of photography. Before modern photographic techniques, chlorargyrite’s natural properties helped capture some of the first photographs, marking a significant milestone in technological history.

Electrum

Electrum presents a fascinating range of colors from pale to bright yellow, depending on its gold and silver content. Its metallic surface shows a softer gleam than pure gold, which earned it the historical nickname “white gold” in ancient times.

The composition of electrum varies significantly, containing anywhere from 20% to 80% gold, with silver making up the remainder. This natural variation creates unique pieces with distinct appearances and properties.

This metal alloy holds a special place in economic history as the material used for the world’s first coins. Around 625-600 BC, the kingdom of Lydia began minting electrum coins, revolutionizing trade and commerce in the ancient world.

The name “electrum” comes from the Greek word for amber, reflecting its pale golden color. Ancient texts, including Homer’s Odyssey, mention this precious metal alloy, highlighting its importance in classical civilization.

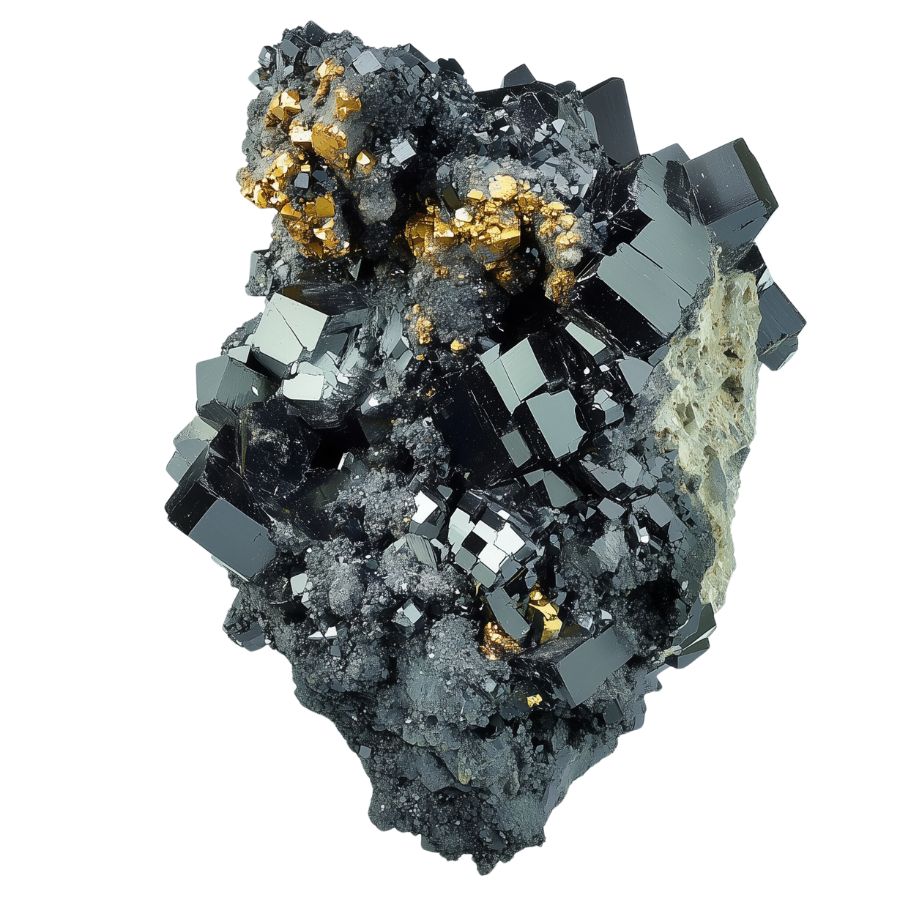

Acanthite

Acanthite presents as dark gray to black crystals with a distinctive metallic shine. These crystals often form elongated prisms or tubes, and sometimes appear in pseudo-cubic shapes.

An interesting feature of acanthite is its ability to change form at different temperatures. Above 173°C, it transforms into a different crystal structure called argentite. This transformation can create unique patterns and shapes in the specimens.

The crystals often group together in complex arrangements, forming branching or tree-like structures. These intricate formations make each specimen unique and visually striking.

Acanthite is considered one of the most important silver ores, second only to argentiferous galena. Its high silver content makes it particularly valuable for collectors and rockhounds.

Proustite

Proustite displays a stunning deep red to scarlet color that immediately catches the eye. Its crystal formations range from delicate prisms to rhombohedral shapes, sometimes reaching up to 8 centimeters in size. The surface shows a glass-like shine that gives specimens an extra touch of beauty.

Its specific gravity ranges from 5.57 to 5.64, indicating a high density due to its silver content.

An interesting feature of proustite is its reaction to light. When exposed to sunlight for extended periods, the bright red color gradually darkens and becomes opaque. This sensitivity makes proper storage essential for maintaining the specimen’s original beauty.

The crystals often form in complex groups, creating striking visual displays. Each crystal can show different faces and angles, making every specimen unique.

Some pieces show perfect crystal formations, while others appear in massive or granular clusters.

SAFETY WARNING: Proustite contains arsenic and should be handled with caution. Always wash hands after handling, avoid creating dust, and never lick or taste specimens.

Sphalerite

Sphalerite comes in an impressive range of colors, from yellow and brown to black and even colorless. This variety in color makes each piece unique.

Sphalerite typically crystallizes in a cubic system, appearing as dodecahedral or tetrahedral crystals, though massive forms are more common.

One of the most fascinating features of sphalerite is its ability to produce light. When scratched or broken in the dark, it creates a brief flash of light – a phenomenon called triboluminescence.

It also glows under ultraviolet light, showing yellow-orange or blue colors depending on its composition.

The crystal surfaces have a distinct shine that can range from diamond-like to resinous. Pure specimens might be transparent, while others are completely opaque. The way light plays off these surfaces can create beautiful effects.

Some specimens show color zoning, where different shades appear in bands or patches within the same crystal. These patterns form naturally during the crystal’s growth and add to its visual appeal.

Pyrite with Trace Silver

Pyrite shines with a bright, brassy-yellow color that earned it the nickname “fool’s gold.” The crystals form perfect cubes, eight-sided shapes, or combinations of both. The surface gleams with a metallic brightness that stays brilliant even after long exposure.

Pyrite has a hardness rating of 6–6.5 on the Mohs scale, making it relatively durable compared to other minerals. It is also non-magnetic and does not fluoresce under ultraviolet light, which are useful characteristics for identification.

Many specimens show striations – fine parallel lines on the crystal faces. These natural markings are like nature’s fingerprints, making each piece distinct.

The surfaces can also develop an iridescent tarnish that adds rainbow colors to the golden shine.

Pyrite has been used historically for various applications, including as a source of sulfur for sulfuric acid production. Its ability to emit sparks when struck against metal made it valuable in fire-starting tools before modern ignitions were developed.

Pyrargyrite

Pyrargyrite shows a beautiful deep red-to-red-gray color that resembles fine ruby. When you look at it closely, you can see its brilliant shine that ranges from glass-like to metallic. The crystals often form in striking prismatic shapes with natural lined patterns on their surfaces.

One fascinating aspect is how the color changes when you move the stone around in light. The deep red can shift to darker tones, creating an interesting play of color.

When scratched, it leaves a distinctive purplish-red mark, which helps identify genuine specimens.

The crystals can form in various ways, from single prisms to complex groups. Sometimes they create star-like patterns or clusters that catch light from multiple angles. These formations make each piece unique and visually striking.

SAFETY WARNING: Pyrargyrite contains antimony, which can be toxic. Always handle with care, avoid creating dust, and wash hands after touching specimens. Keep away from children and store in well-ventilated areas.

Polybasite

Polybasite appears black at first glance but holds a surprising secret. When held up to strong light, it reveals beautiful dark ruby-red reflections from within. These internal flashes of color make each specimen special and exciting to examine.

The crystals typically form thin, plate-like shapes that sometimes group together in rose-like patterns. This distinctive growth pattern creates interesting layers that catch light differently from various angles.

An interesting feature of polybasite is its ability to form two different crystal structures – trigonal and monoclinic. This dual nature isn’t common in minerals and makes each piece potentially unique in its formation.

Freieslebenite

Freieslebenite displays a pale steel-gray to silver-white color with a bright metallic shine. The crystals often show clear striped patterns along their length, making them easily recognizable.

It is named after Johann Carl Freiesleben, a notable mining commissioner—which adds to its allure among enthusiasts who appreciate the stories behind mineral discoveries.

The crystals frequently form as long, prismatic shapes. They sometimes appear alone, but often grow together in groups that create striking geometric patterns. The surface shine stays consistent even as you turn the specimen in different directions.

The mineral often contains small inclusions of other minerals, which can create interesting patterns within the crystals. These natural imperfections add character to each specimen and make every piece unique.

SAFETY WARNING: Freieslebenite contains lead and antimony, making it potentially hazardous. Always handle with care, avoid creating dust, and wash hands thoroughly after handling. Keep specimens in sealed containers and away from children.

What Rough Silver Looks Like

Identifying a rough silver might seem tricky, but with a few tips, you can spot one even if you’re not a rock expert. We’re going to give you some great tips now.

Real quick before we jump into that we wanted to cover rock and mineral identification in general.

Look for the Distinct Metallic Sheen

Raw silver typically shows a bright, metallic luster which is a whiter, more platinum-like shine. When tarnished, it’ll have dark gray or blackish patches.

Fresh surfaces exposed by scratching will reveal that characteristic silvery-white color.

Pro tip: Use your phone’s flashlight to check how light reflects off the surface – genuine silver will maintain its whitish gleam even under bright light.

Check the Malleability with a Gentle Scratch

Got a copper penny? Try scratching the stone gently. Silver’s pretty soft (2.5-3 on the Mohs scale) and will actually leave a silvery streak.

If it’s super hard or leaves a dark streak, you’re probably looking at something else. The surface might show some natural indentations or marks because of silver’s softness.

Examine the Surface Texture

Real silver ore often appears in thread-like or wire-like formations. Sometimes you’ll spot cube-shaped or octahedral crystals.

The surface usually isn’t smooth – expect a somewhat dendritic (tree-like) or reticulated pattern. Run your finger across it; authentic silver ore feels surprisingly heavy for its size and slightly greasy to the touch.

Test the Temperature Conductivity

Here’s a cool trick: hold the stone in your palm for 30 seconds. Silver’s an excellent conductor, so it’ll quickly warm up to your body temperature. If it stays cold longer, it might be another mineral.

Also, check if water droplets spread out quickly on the surface – silver’s high conductivity causes this distinctive behavior.

A Quick Request About Collecting

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Tips on Where to Look

Once you get to the places we have listed below there are some things you should keep in mind when you’re searching:

Rocky Cliffs and Outcrops

Start by looking at exposed rock faces, especially those with white or gray quartz veins running through them. Silver often hides in these veins alongside other shiny minerals.

The surrounding rock might have a rusty red or dark gray color. Bring a rock hammer and safety glasses, and carefully check any chunks of rock that feel unusually heavy for their size.

Creek Bottoms

Get yourself a gold pan and head to creeks near old mining areas. Look for places where the water slows down – like behind big rocks or at sharp bends.

Silver is heavy, so it settles in the same spots where you might find black sand. Focus on the bottom layer of sand and gravel when panning. The silver will often appear as small, shiny flakes or nuggets.

Old Mine Areas

Search through rock piles near historic mining sites (with permission). Miners often missed smaller pieces of silver-bearing rock.

Look for rocks with a gray metallic shine or those that are surprisingly heavy. A UV light can help, as some silver minerals glow under ultraviolet light.

Always wear sturdy boots and watch for unstable ground.

Rock Cracks and Caves

Silver deposits often form in cracks and small caves where mineral-rich water once flowed. Look for areas where different types of rock meet, especially where light-colored granite touches darker rock.

These contact zones are prime spots for silver deposits. Bring a flashlight and look for metallic streaks or patches on the walls.

Mountain Stream Banks

Check eroded stream banks in mountainous areas, especially after heavy rains. Silver-bearing rocks often wash out of higher ground and collect along stream edges.

Look for unusually heavy pieces with a metallic luster. The best spots are usually where the stream makes a sharp turn or where several smaller streams come together. Dig a few inches into the gravel at these points.

Some Great Places To Start

Here are some of the better places to start looking for silver in Massachusetts:

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Newbury

Newbury is a town located in Essex County, Massachusetts, in the northeastern part of the state. It is situated along the coast, near the Merrimack River, and includes the villages of Old Town (Newbury Center), Plum Island, and Byfield.

The area’s unique geology features glaciomarine sediments and notable gabbro-diorite and granite intrusions. The mine area is particularly rich in galena, pyrite, and siderite alongside silver deposits.

The best silver specimens can be found around the old Chipman Mine site, particularly in the mineralized zones where the ore veins intersect with the surrounding rock.

The site gained additional geological significance following the 1727 earthquake, which left distinctive liquefaction features in the local rock formations, making it an important location for both mineral collectors and geological researchers.

Mount Peak Mine

Mount Peak Mine sits in the rugged terrain of Charlemont, Franklin County, Massachusetts, close to the Vermont border. The site, formerly known as Hawks Pyrite Mine, features a 150-foot deep shaft with several adits and drifts that showcase the area’s rich mineral deposits.

The mine’s geology is distinguished by its stratabound massive sulfide deposits, similar to those at the nearby Davis Pyrite Mine. Silver deposits are typically found within the pyrite-rich zones, particularly where chalcopyrite is present.

The surrounding Berkshire Hills add to the site’s geological significance, with metamorphic rock formations that date back millions of years.

For silver seekers, the most promising areas are the sulfide-rich veins exposed in the mine’s walls and remaining tailings.

Manhan Mine

The Manhan Mine is a former lead-silver mine located in Easthampton, Hampshire County, Massachusetts. It is part of the Loudville Lead Mines, situated near the village of Loudville, which straddles the Easthampton-Westhampton town line.

The mine’s unique hydrothermal fault deposits created ideal conditions for mineral formation. The main vein is exceptionally rich, yielding 76% lead with approximately twelve ounces of silver per ton – a remarkable concentration for the area.

Silver specimens can be found in the mine dumps along the North Branch of the Manhan River. The area’s geology includes galena (lead sulfide), which often contains silver.

Rock collectors frequently discover secondary minerals in the dump piles, including anglesite, cerussite, and pyromorphite, alongside silver-bearing specimens.

Chipman Mine

The Chipman Mine, also known as the Merrimac Mine, sits in Newbury, Massachusetts, about 4.2 kilometers west of Newburyport. This historical mining site operated during two main periods: 1874-1879 and 1919-1925, marking significant silver production in Massachusetts.

The mine’s geology features an impressive mineralized vein system within a complex of gabbro-diorite and granite formations. The site’s unique mineral composition also includes sphalerite, chalcopyrite, and pyrite.

The most productive area for finding silver-bearing minerals is near the old mine dumps and around the main shaft area. The mine’s waste rock piles still contain traces of galena, which often indicates the presence of silver mineralization.

Thompsonville Silver Mine

The Thompsonville silver mine is located in Newton, Middlesex County, Massachusetts, near Hammond’s Pond woods.

The site gained attention in the late 19th century when silver deposits were discovered in the area. The geological makeup consists primarily of metamorphic rocks, which created ideal conditions for silver mineralization.

The Boston Basin’s unique geological history, formed during the late Proterozoic era, contributed to the formation of these silver deposits.

Today, remnants of the old mining operations can still be seen near Hammond’s Pond. The silver deposits occur within veins of metamorphic rock formations, particularly concentrated in the southern section of the site.

While not a commercial mine anymore, this location offers rockhounds a chance to explore a piece of Massachusetts mining history.

Places Silver has been found by county

After discussing our top picks, we wanted to discuss the other places on our list. Below is a list of the additional locations where we have succeeded, along with a breakdown of each place by county.

| County | Location |

| Franklin | Davis Pyrite Mine |

| Hampshire | Betts Manganese Mines |

| Middlesex | Badger Farm locality |