Porcini mushroom hunting in Florida offers a surprising mix of challenge and reward for foragers who know where to look. The state’s patchy pinewoods and seasonal rains can produce just the right conditions for these prized fungi to appear in the right places.

When cooked, porcini have a firm bite and hold their shape beautifully in everything from brothy soups to skillet dishes. That texture, paired with their deep umami richness, is why chefs around the world value them so highly.

Drying porcini brings out their most concentrated flavors, and even the liquid left from soaking them can become a bold, earthy base for cooking. Because of this, high-quality dried specimens often command hefty prices in specialty markets.

Fresh porcini can fetch upwards of sixty dollars a pound in many parts of the country, especially when the season is short. Knowing which forests or preserves to search can mean going home with a haul that includes not just porcini, but an incredible mix of other wild mushrooms as well.

What We Cover In This Article:

- What different types of Porcini mushrooms look like

- The mushrooms that look like Porcini you should avoid

- Our best tips for finding Porcini mushrooms

- The top places in the state to find porcini

- The best times of year to look for them

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

What Porcini Mushrooms Look Like

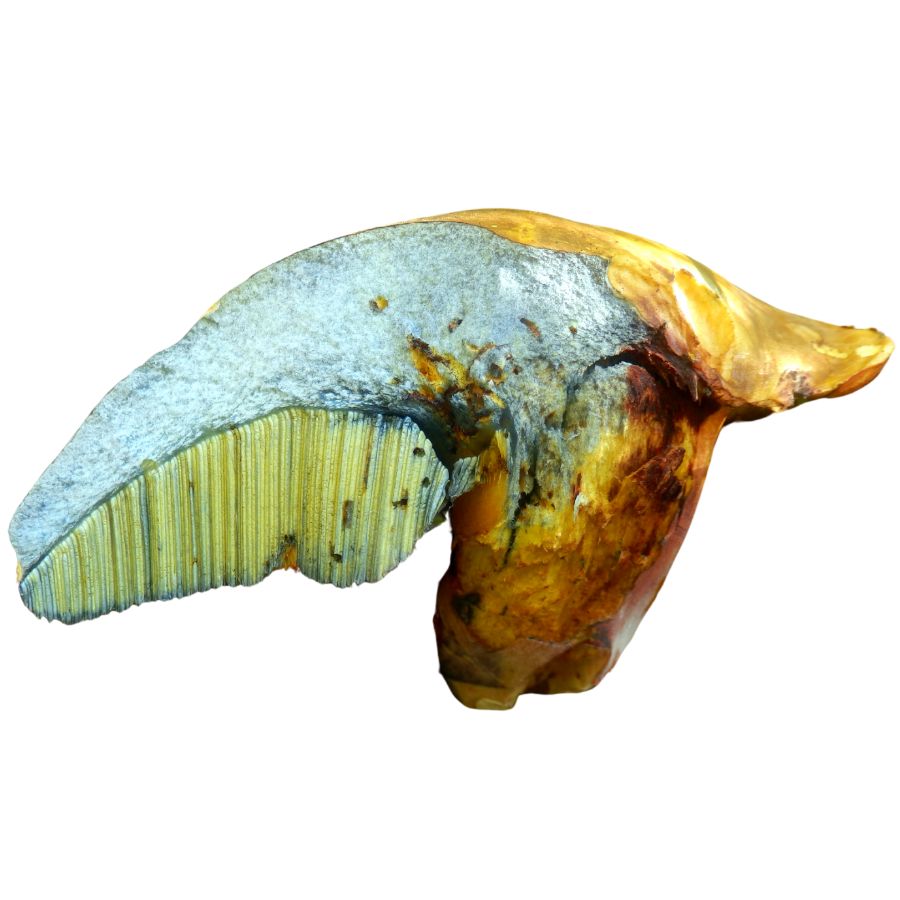

Porcini technically refers to one mushroom species: Boletus edulis, also known as the king bolete. But in many parts of the U.S., several other edible mushrooms in the same genus or family are also called porcini. These close relatives belong to the broader Boletus group and share a similar look, taste, and texture:

Porcini (Boletus edulis)

Porcini, also known as king bolete, cèpe, or penny bun, is a large, thick-stemmed mushroom with a smooth brown cap and a sponge-like underside instead of gills. Its firm white flesh has a nutty, earthy flavor that holds up well in cooking and drying. This species is the classic or “true” porcini.

It’s most commonly found in the Pacific Northwest, especially in coastal forests of Oregon, Washington, and Northern California. It grows in coniferous woods, often near spruce, fir, or pine, and usually appear in the fall after consistent rainfall.

California King Bolete (Boletus edulis var. grandedulis)

The California king bolete, sometimes called the Sierra porcini or just king bolete, is a large, stocky mushroom with a smooth brown cap and a thick white stem. It has a firm texture and a deep, nutty flavor that holds up well in cooking.

This porcini variety grows in the Sierra Nevada and coastal forests of California, especially from fall through early winter. It prefers mixed woodlands with fir, pine, or tanoak and often appears after the first heavy rains of the season.

Spring King Bolete (Boletus rex-veris)

The spring king bolete, often called the spring porcini, has a pale brown cap, a stout white stem, and a firm texture that stays intact during cooking. Its flavor is rich and earthy, with a slightly sweet finish that sets it apart from other boletes.

You’ll find this mushroom in the western mountains of the United States, especially in California, Oregon, and parts of the Rocky Mountains. It appears in high-elevation conifer forests in late spring and early summer, usually near snowmelt.

White King Bolete (Boletus barrowsii)

The white king bolete, sometimes called Barrows’ bolete or desert porcini, is a pale, chunky mushroom with a white to ivory cap and a thick stem. It has a smooth, mild flavor that deepens when cooked and is especially prized when young and firm.

It grows in the southwestern United States, especially in Arizona and New Mexico, and is often found in ponderosa pine forests. Unlike other porcini, it tends to fruit during the summer monsoon season after warm rains.

Almost Bluing King Bolete (Boletus subcaerulescens)

The almost bluing king bolete, also known as the blue-staining porcini, has a light brown cap and a stout stem covered in a fine network of raised lines. It gets its name from the faint blue tint that sometimes shows near the base when cut, though the color change is subtle and doesn’t always appear.

This porcini is edible and well-regarded for its firm texture and mild, nutty flavor. It cooks up nicely in sautés or soups and holds its shape without turning mushy.

It grows around the Great Lakes and into the Northeast, favoring mixed forests with spruce, fir, or pine and usually shows up in late summer after steady rain.

Fib King (Boletus fibrillosus)

The fib king, sometimes called the fuzzy porcini, has a dark reddish-brown cap with a matte, finely fibrous surface and a thick pale stem. Its dense flesh has a mild, pleasant flavor that deepens when cooked, making it a solid addition to savory dishes.

You can find this mushroom is found in the Pacific Northwest, especially in the coastal forests of Oregon and Washington. It prefers old-growth conifer forests and usually fruits in the fall after sustained rain.

Mushrooms That Look Like Porcini But Aren’t

In this state, a handful of mushrooms resemble porcini at first glance. Knowing the differences can help you avoid a bad meal or worse:

Satan’s Bolete (Boletus satanas)

Satan’s bolete is a large, thick mushroom with a pale, almost white cap and a bright red stem. The pores underneath are yellow but bruise blue when handled, making it stand out from other boletes in the woods.

It grows in warmer parts of the southeastern U.S., especially in hardwood forests with oak or beech. This mushroom is toxic and should never be eaten as it can cause severe gastrointestinal distress including vomiting and diarrhea.

Sensitive Bolete (Boletus sensibilis)

Sensitive bolete, sometimes called the “bruise bolete,” is known for how quickly it turns blue when touched or cut. It has a smooth yellow cap, red or pinkish pores, and a yellow stem that often shows bruising almost instantly.

You can find it across the eastern and southeastern U.S., especially in mixed hardwood forests during summer. While it might look appealing, this mushroom is considered toxic and can cause stomach cramps, nausea, and vomiting if eaten. Even small amounts may lead to unpleasant symptoms, so it’s best left alone.

Huron Bolete (Boletus huronensis)

Huron bolete is a chunky mushroom with a dull brown cap, yellow pores, and a thick, slightly reddish stem that bruises blue when handled. It may not look as bold as other toxic boletes, but it’s still one to avoid.

Sometimes called the “Great Lakes bolete,” this species is found in the Great Lakes region, especially in Michigan and nearby states, growing under hardwoods like oak and beech. It’s considered poisonous and can cause intense nausea, cramps, and vomiting. While not deadly, the symptoms can be severe enough to require medical attention.

Bitter Bolete (Tylopilus felleus)

Bitter bolete, also called the “bitter tasting bolete,” looks a lot like an edible porcini at first glance. It has a brown cap, pinkish pores, and a thick, netted stem that can fool even experienced foragers.

This mushroom grows widely across the country, especially in eastern forests with oak or pine. It isn’t toxic, but the taste is so bitter that even a small piece can ruin a whole dish. Most people spit it out right away, but if swallowed, it can still lead to mild stomach upset.

Two-colored Bolete (Baorangia bicolor)

Two-colored bolete, sometimes called the “bicolor bolete,” has a bright yellow stem and cap with deep red tones near the base and edge. The pores are yellow and stain blue when touched, giving it a bold and colorful look.

It’s found across the eastern U.S., especially in oak and mixed hardwood forests during summer and fall. This species is edible and often enjoyed for its mild flavor and tender texture when cooked. Some people report digestive discomfort, so it’s best to test small amounts first.

How to Find Porcini Mushrooms

Porcini mushrooms don’t show up just anywhere. They grow in very specific places, and understanding the right mix of trees, soil, and seasonal conditions is the key to finding them.

Focus on Mixed Forests with Both Hardwoods and Conifers

Mixed hardwood and conifer forests are common habitats for porcini mushrooms. In the Northeast, mature oak-maple forests with scattered hemlocks are good spots. In the Rockies and the Pacific Northwest, they thrive in higher-elevation forests dominated by spruce and fir.

Old-growth or long-established forests are usually more productive than young stands.

Wait Several Days After a Steady Rainfall

Consistent moisture is key. These mushrooms tend to appear several days after steady rain, especially if followed by warm temperatures.

They rarely grow during droughts or in overly wet, swampy areas. A moist but not soggy forest floor is ideal.

Search in Loose, Acidic Soil with Plenty of Leaf Litter

Porcini and their close relatives grow best in well-drained soils that are slightly acidic. Sandy loam or loose forest soil rich in organic material tends to support healthy mushroom growth.

They are rarely found in compacted or heavily clay-based ground. Look for them where the topsoil is crumbly and full of leaf litter.

Check Near Animal Paths, Broken Branches, and Debris Piles

Porcini and edible boletes often grow near the edges of clearings, trails, or small breaks in the canopy. These spots get dappled light, which helps warm the soil while keeping it moist.

Look along well-used animal paths or areas with broken branches and scattered debris. These partial openings tend to support just the right conditions for a flush.

Follow Animal Dig Marks and Shifts in the Forest Floor

On the forest floor, mossy patches are good indicators for mushrooms. Porcini may push up under duff, creating small mounds or cracks in the soil. Displaced needles, uneven ground, or fresh animal dig marks can sometimes point to hidden mushrooms nearby.

Pay attention to slight changes in texture or elevation underfoot.

Focus on North-Facing Mountain Slopes

In mountain regions, porcini and edible boletes tend to appear between 5,000 and 9,000 feet. They favor gentle slopes with good water runoff but not erosion.

South-facing slopes may dry too quickly, while north-facing ones hold moisture longer. Sloped terrain with a soft duff layer is often productive after summer rains.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

Where You Can Find Porcini

Porcini mushrooms tend to grow in specific forests across the state, often tied to elevation, soil type, and tree cover. Knowing where to look can make all the difference in finding them during their short fruiting season.

Apalachicola National Forest

Apalachicola National Forest is the largest national forest in Florida, known for its vast wetlands, longleaf pine savannas, and winding blackwater rivers. Within this sprawling landscape, there are specific places where the conditions align just right for porcini mushrooms to grow beneath the canopy.

One area that tends to support porcini is the region around Fort Gadsden Historic Site, where oak and pine mingle along the Apalachicola River floodplain. The mixed hardwood forests and sandy soils near the bluff provide a shaded, well-drained environment where porcini can thrive during wetter months.

South of Sumatra, the sandy uplands near Owl Creek and Kennedy Creek contain pockets of mature pine and hardwood stands that hold moisture surprisingly well for the region. These higher ridges, scattered with leaf litter and shielded from intense sun, offer a favorable combination of tree cover and soil composition for porcini.

Farther east, the shaded corridors along the Wright Lake Trail loop through areas of dense forest where porcini have been spotted in seasons past. The trail passes through stretches of live oak, hickory, and loblolly pine that create just the kind of environment porcini seem to prefer.

Ocala National Forest

Ocala National Forest is home to some of the largest contiguous sand pine scrub habitats in the world. That distinct terrain doesn’t stop the forest from also harboring places where porcini mushrooms are known to thrive under the right seasonal conditions.

Along the Yearling Trail near Pat’s Island, the hardwood hammocks interspersed with longleaf pine provide scattered pockets of damp, shaded ground rich in leaf litter. This blend of tree cover and moisture makes it one of the more promising areas in the forest where porcini can emerge after sustained rainfall.

Near Juniper Prairie Wilderness, you’ll find patches of mixed oak and pine just off the western edges of Juniper Creek. These mixed woodlands, especially near shallow drainages, tend to support the kind of microhabitats that porcini prefer—quiet, undisturbed, and rich in mycorrhizal partners.

Around Lake Delancy, the low-lying forest surrounding the western shore is dotted with loblolly and live oaks. This area, particularly just off the trails that skirt the lake, has a history of holding moisture longer into the dry months, giving porcini a better shot at pushing through the duff.

Osceola National Forest

Osceola National Forest is home to one of the largest expanses of flatwoods in Florida, with vast stretches of longleaf and slash pine habitats. In this mix of pine-dominated uplands and wetter lowland hammocks, there are several areas where porcini mushrooms are likely to grow.

Ocean Pond, a natural lake surrounded by pine and hardwood forest, holds promise for finding porcini along its shaded edges. The leaf litter beneath mixed oak and pine stands near the lake provides the kind of moisture and tree association porcini prefer.

To the north, the Deep Creek area offers another good pocket of habitat, especially near where forest roads cross the creek and hardwoods are more dominant. The blend of sandy soil, moisture from the waterway, and nearby mature oaks gives porcini a solid foothold in this part of the forest.

Further west, the fringes of the Hunt Camp area off Forest Road 267 show signs of the right conditions—older pine stands, intermittent oak, and undisturbed leaf litter. Porcini can also turn up along less-traveled stretches of the Florida Trail, especially where it dips into wetter, oak-lined zones.

Tate’s Hell State Forest

Tate’s Hell State Forest spans over 200,000 acres of swamplands, pine flatwoods, and floodplain forests along the Florida Panhandle’s Forgotten Coast. Its name comes from a local legend involving a desperate trek through the swamps, but today it’s known more for its wild biodiversity and patchwork of distinct ecosystems.

Some of the best spots for finding porcini mushrooms in the forest are tucked near the waters of Whiskey George Creek. The surrounding mixed hardwood and pine stands offer the shaded, leaf-littered conditions these mushrooms tend to favor, especially after steady summer rains.

Further west, the area around High Bluff Landing Road winds through elevated pine-oak hammocks that drain well but still retain moisture along the margins. Porcini are often found here among the oaks and scattered sandhills, particularly where dense groundcover and decomposing duff help keep the soil cool and damp.

In the eastern section of the forest, around Forest Road 22 near the Crooked River, you’ll find patches of mature longleaf and slash pine dotted with hardwood clusters. These transitional zones provide a productive mix of tree species and soil conditions where porcini can show up.

Withlacoochee State Forest

Withlacoochee State Forest is home to over 155 miles of trails, winding through some of the most ecologically diverse land in central Florida. Scattered among those trails are several areas where porcini mushrooms are likely to grow under the right conditions.

Croom Tract, on the west side of the forest near Silver Lake, has pockets of oak and pine that create the kind of shaded understory porcini favor. Moist depressions near the river and along the lesser-used segments of the Croom Loop Trails hold onto enough humidity to support a healthy flush when the season is right.

In the Richloam Tract, areas near Gator Hole Grade and the upper stretches of the Little Withlacoochee River provide a mix of conditions that line up well with known porcini habitats. You’ll notice that the hardwood-pine blend in these corridors produces a dense layer of mycorrhizal partners critical to porcini development.

Further south, the Tillis Hill area sits at a slightly higher elevation but still retains enough seasonal moisture in its shaded hollows. The woodlands surrounding Tillis Hill Trail and the nearby horse campground support stands of trees commonly associated with porcini in other parts of the Southeast.

Additional Locations to Find Porcini

There are several reliable locations across the state where porcini mushrooms grow:

| Panhandle | Porcini Collection Details |

| Blackwater River State Forest | Foraging for personal use only |

| Tate’s Hell State Forest | Permit required for foraging |

| Pine Log State Forest | Limited foraging allowed in designated areas |

| Apalachicola National Forest | Foraging allowed with seasonal restrictions |

| North Florida | Porcini Collection Details |

| Osceola National Forest | Foraging allowed for personal consumption |

| Jennings State Forest | Foraging for personal use only |

| Etoniah Creek State Forest | Permit may be required for foraging |

| Central Florida | Porcini Collection Details |

| Lake George State Forest | Seasonal foraging allowed in marked zones |

| Welaka State Forest | Foraging limited to non-protected species |

| Little Big Econ State Forest | Foraging allowed in accordance with state rules |

| Seminole State Forest | Foraging for non-commercial purposes only |

| Ocala National Forest | Foraging permitted with some species restrictions |

| Withlacoochee State Forest | Personal use foraging allowed in some areas |

When You Can Find Porcini

Porcini mushrooms are one of the most sought-after wild edibles in North America. Their meaty texture and rich, nutty flavor make them a favorite among foragers and chefs alike. Knowing when they appear is key if you want to find them in good condition and before the bugs do.

In most western states, porcini season usually runs from late summer into fall. You can start checking in July at higher elevations and continue through September or October depending on the region. In places like the Pacific Northwest and the Rocky Mountains, the timing often lines up with the first good rains after a dry spell.

In the eastern US, porcini mushrooms tend to fruit earlier. They often show up between late spring and mid-summer, especially in hardwood forests with oak or beech. A warm, wet stretch of weather can bring them up quickly, sometimes just days after a heavy rain.

Some parts of the country even have a second flush in the fall. Areas with mixed forests and a long growing season may see porcini pop up again in September or October. Local timing varies a lot, so it helps to learn what to expect in your state and watch the weather closely.

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.