Platinum hunting exists right here in Ohio. Most folks think they need to head west to strike it rich, but that’s not true. Some areas within our state borders hold this valuable metal.

But, looking for platinum takes time and patience. The shiny metal doesn’t just sit out in the open waiting to be picked up. It hides in certain rocks and soil types across different parts of the state.

The search pays off when you know where to look. This article will show you several spots where others have found platinum before. We’ll walk through each area and explain why platinum might be there.

How Platinum Forms Here

Platinum forms deep within Earth’s mantle, about 90-125 miles below the surface. This precious metal starts its journey when molten rock cools very slowly under extreme pressure.

Unlike gold, platinum rarely forms large nuggets. Instead, it typically appears as tiny grains mixed with other rocks. When ancient volcanoes erupt, they sometimes bring platinum-bearing rocks closer to the surface.

Over millions of years, weathering breaks down these rocks, and the heavy platinum particles get washed into streams and riverbeds.

Most platinum comes from places where parts of the mantle pushed up through the crust long ago. Miners often find platinum alongside nickel and copper deposits in igneous rocks.

Some platinum forms when meteor impacts create the perfect temperature and pressure conditions for these rare metals to crystallize.

Platinum Host Rocks

Platinum is a rare and valuable metal that occurs naturally in certain geological formations. These formations, often ultramafic and mafic igneous rocks, are significant hosts for platinum mineralization. Below is an overview of ten such rock types and geological settings associated with platinum deposits:

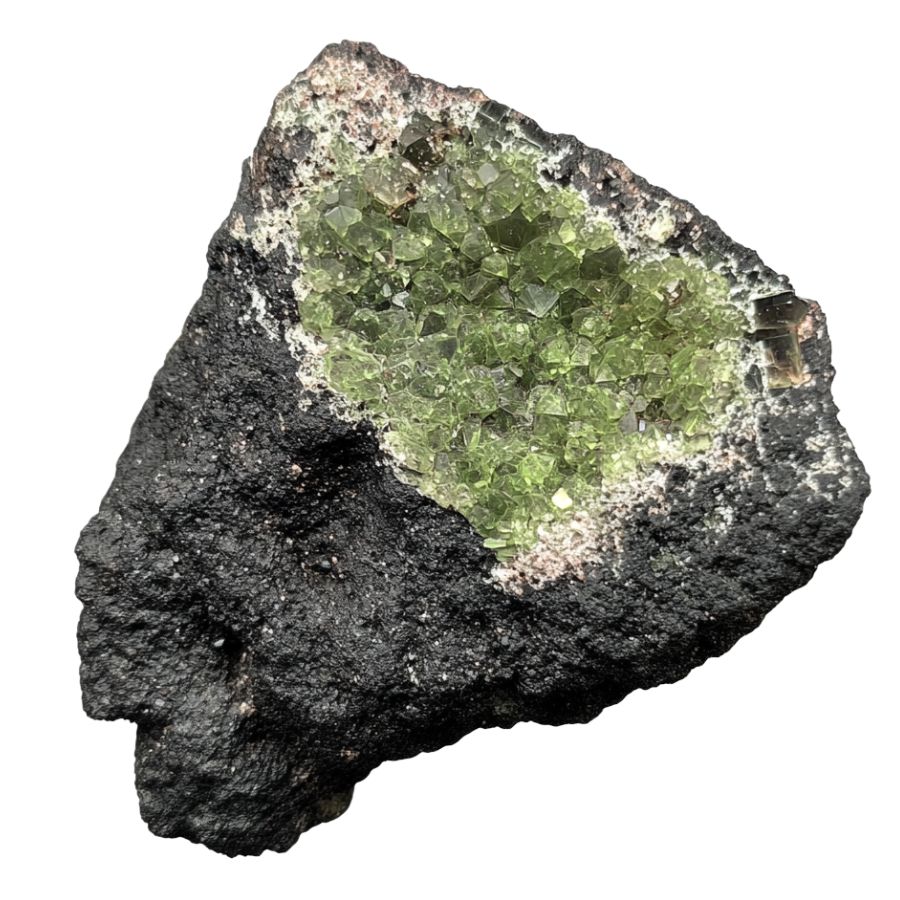

Peridotite

Peridotite is a green igneous rock that forms deep within the Earth’s mantle. Its striking color comes from its main mineral, olivine, with black specks from minerals like chromite or magnetite adding contrast. Unlike other similar rocks, peridotite contains less than 45% silica.

This special rock serves as a natural home for platinum. The precious metal hides inside peridotite as tiny grains, sometimes too small to see without a microscope.

Platinum in peridotite often teams up with other valuable metals like palladium, rhodium, and iridium. Miners search for areas where natural processes have concentrated these platinum grains into richer deposits.

When you see platinum jewelry, there’s a good chance the metal originally came from peridotite deep beneath the Earth’s surface.

Dunite

Dunite is an olive-green to yellowish-green rock with a speckled appearance. It has a coarse texture where you can see individual mineral grains. Unlike other similar rocks, dunite consists of more than 90% olivine, giving it a more uniform green color than peridotite or harzburgite.

Platinum loves to hide in dunite rocks, especially in areas with lots of chromite minerals. The platinum in dunite often appears as tiny metal flakes or as minerals mixed with arsenic compounds.

Over millions of years, as the magma cools and crystals grow, platinum gets caught between the olivine minerals. Some of the world’s most valuable platinum comes from dunite that formed over a billion years ago.

Harzburgite

Harzburgite displays a dark green to greenish-black color with a speckled appearance. It features olive-green olivine crystals mixed with darker orthopyroxene minerals. Unlike dunite, harzburgite contains significant amounts of orthopyroxene alongside olivine but has less clinopyroxene than other peridotite varieties.

The platinum in harzburgite tells an interesting story about Earth’s inner workings. This rock forms through a process called partial melting, which concentrates platinum in the remaining solid material.

As magma bubbles up through Earth’s mantle, harzburgite acts like a natural filter, sometimes collecting platinum along with other rare metals. Platinum hunters look for harzburgite that contains tiny sulfide minerals, as these often hold the precious metal.

The platinum in harzburgite is especially valuable because it forms under extreme conditions that are hard to reproduce in laboratories, making each deposit unique.

Pyroxenite

Pyroxenite comes in dark green, black, or light green colors with layered, banded, or veined patterns throughout the rock. It has a range of luster from dull to vitreous or even slightly metallic. Unlike peridotite varieties, pyroxenite contains mostly pyroxene minerals like augite and diopside, with little to no olivine.

Platinum finds a perfect home in pyroxenite rocks, often forming rich deposits that miners treasure. The special mineral makeup of pyroxenite creates ideal conditions for platinum to concentrate, especially along layer boundaries where different minerals meet.

When magma slowly cools to form pyroxenite, platinum particles get trapped in growing crystals or settle between layers. Sometimes, the platinum in pyroxenite appears as its own minerals like sperrylite, which contains platinum and arsenic. Other times, it hides inside sulfide minerals alongside copper and nickel.

Geologists use sophisticated tools to find these platinum-rich zones in pyroxenite, looking for subtle clues that indicate where the precious metal might be hiding.

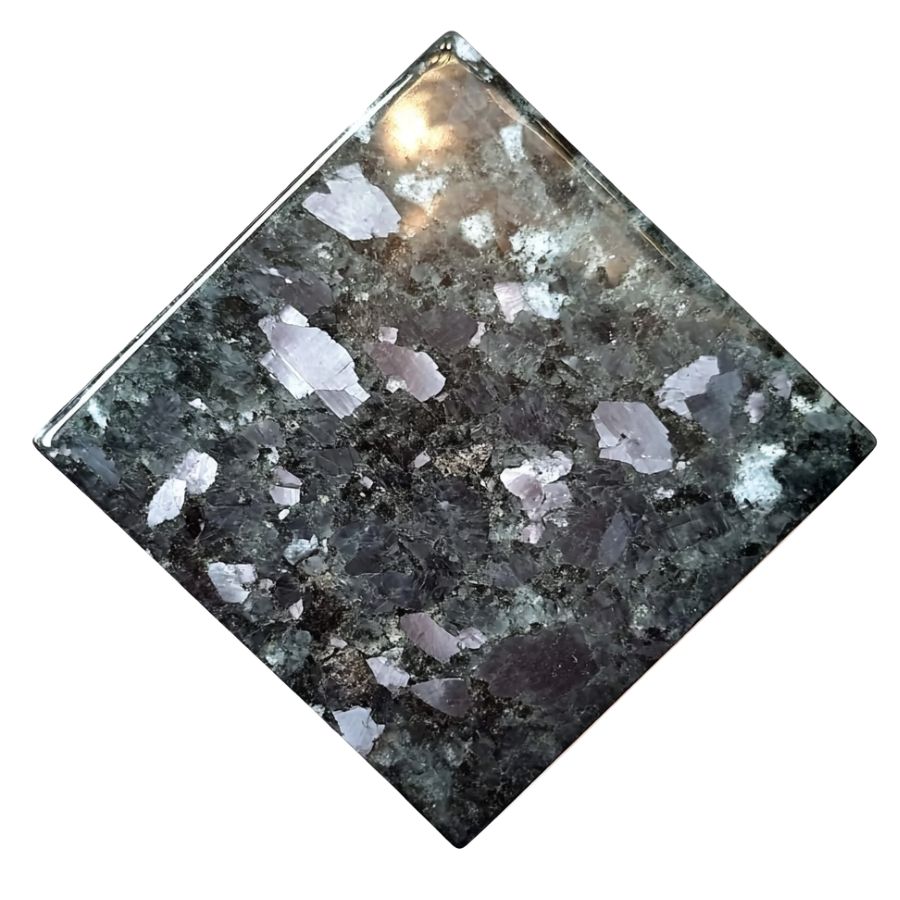

Norite

Norite is a dark gray to greenish-black rock with visible salt-and-pepper speckles. These speckles come from the light-colored plagioclase feldspar mixed with dark orthopyroxene minerals. The rock has a coarse texture where you can see individual crystals without a magnifying glass.

Platinum in norite typically appears alongside other valuable metals, creating treasure troves beneath the surface. Unlike in some other rocks, platinum in norite often forms during the cooling of magma chambers, when the metal concentrates in specific layers as the liquid rock solidifies.

The platinum minerals in norite can take various forms – sometimes as pure metal flakes, sometimes as compounds with sulfur or other elements. These differences affect how miners extract the platinum and how much the deposit is worth.

Gabbro

Gabbro is a dark-colored rock with visible crystals of white to gray feldspar mixed with black or dark green minerals. Its coarse texture comes from slow cooling deep underground, letting the crystals grow large enough to see easily. Unlike granite, which is light-colored with lots of quartz, gabbro is much darker and heavier.

When platinum appears in gabbro, it often creates some of the most valuable metal deposits on Earth. The platinum doesn’t spread evenly through the rock, instead, it concentrates in special zones that formed as the magma cooled and different minerals crystallized. These zones sometimes look like layers or bands running through the gabbro.

The platinum in gabbro usually teams up with metals like palladium, creating a natural alloy. Sometimes, it forms its own minerals with sulfur or arsenic. Because gabbro is so tough and resistant to weathering, mining platinum from it can be challenging but very rewarding.

Anorthosite

Anorthosite is a light-colored rock, usually white to light gray. Unlike most igneous rocks that contain various minerals, anorthosite is made up of more than 90% plagioclase feldspar, with very few dark minerals. This gives it a much lighter appearance than similar rocks like gabbro or norite.

The platinum in anorthosite systems often appears with copper and nickel minerals, forming complex patterns that geologists work hard to understand.

When studying anorthosite for platinum potential, scientists look for subtle color changes or mineral differences that might signal the presence of the valuable metal. The contrast between light anorthosite and the darker minerals that sometimes contain platinum makes these deposits particularly interesting.

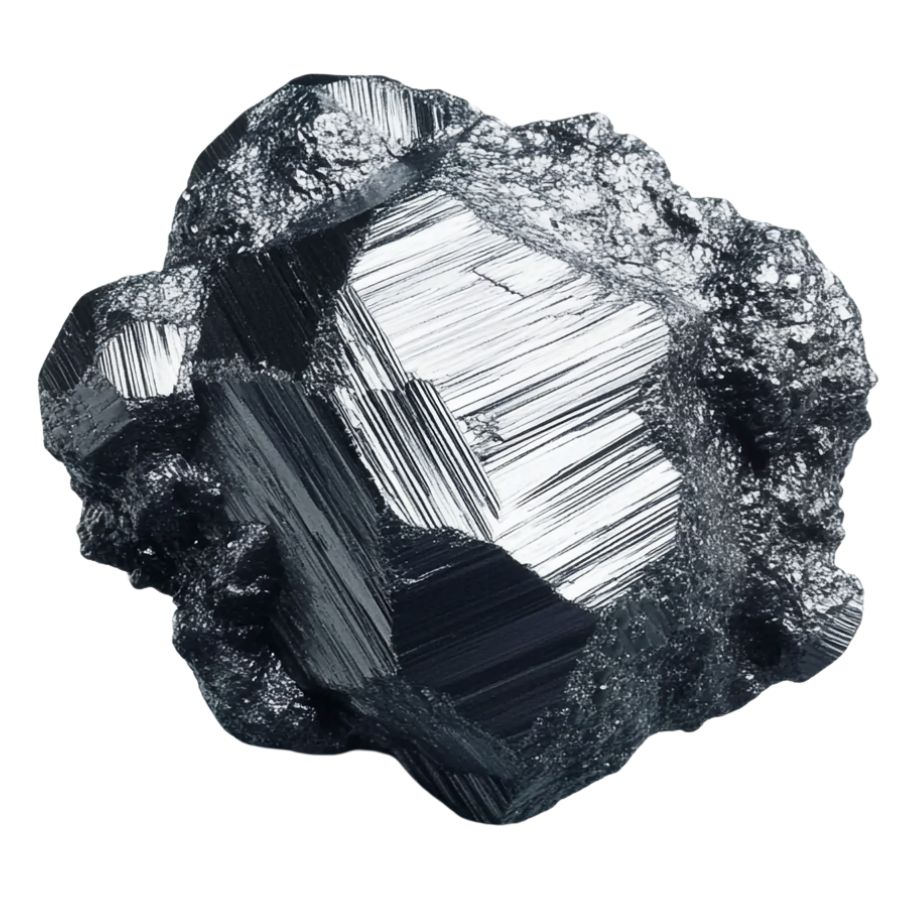

Chromitite

Chromitite is a dark, almost black mineral with a metallic to slightly greasy shine. When you look at it closely, it might have dark gray or brown-black tones. Unlike similar-looking minerals, chromitite forms in distinct masses or layers within certain rock types, especially in rocks related to ancient volcanoes.

Platinum in chromitite often appears as tiny grains nestled between the chromite crystals or as microscopic particles inside the crystals themselves. When geologists find thick layers of chromitite, they get excited about the platinum potential.

The relationship between chromium and platinum remains somewhat mysterious, but we know that the same geological processes that concentrate chromium often gather platinum too.

Some chromitite layers contain so much platinum that even though the metal is invisible to the naked eye, these rocks become some of the most valuable materials on Earth.

What Does Rough Platinum Look Like?

When found in the wild, rough platinum has distinctive qualities that separate it from other similar-looking minerals. Here’s how to spot it even if you’re not a rock expert.

Check for a Silvery-Gray or Steel Color

Raw platinum usually has a silvery-gray or steel-like appearance with a dull metallic luster. Unlike silver, it won’t tarnish or develop a blackened surface over time. It also lacks the brassy or yellowish tone of minerals like pyrite (fool’s gold).

Sometimes, native platinum may appear slightly darker due to natural coatings or mineral impurities. If you gently scratch the surface, you might expose a brighter metallic streak underneath — a good sign you’re on the right track.

Also, it won’t show rainbow flashes or colorful reflections like some other shiny minerals.

Look for Rounded, Worn Nugget Shapes

In nature, platinum typically appears as small nuggets, grains, or flattened flakes. These pieces often have smooth, rounded edges, especially if they’ve been tumbled in a stream or river. They can look a bit like dull silver pebbles — dense, worn, and irregular.

Crystalline platinum is extremely rare, so don’t expect sharp edges or well-defined shapes. Instead, look for odd but smoothed forms, like tiny clustered balls or slightly squished flakes.

Test the Surprising Heaviness

If you pick up a small piece and it feels unusually heavy for its size, that’s a strong clue. It’s denser than silver, lead, and even gold, giving it a distinct heft in your hand.

While it’s only slightly heavier than gold, it’s noticeably denser than most rocks or minerals you’ll come across. That weight, combined with color and shape, makes rough platinum easier to spot once you know what to look for.

What About Platinum Ore?

Platinum is often found in ore rather than as pure nuggets, especially in hard rock deposits. These ores usually come from ultramafic or mafic igneous rocks like peridotite, dunite, or chromitite. The rock might look dark, heavy, and unremarkable — but can contain microscopic grains of platinum group metals.

Visually, platinum ore doesn’t usually stand out. It’s often associated with other metals like nickel, copper, and iron, and may have a greenish or dark gray color with metallic flecks.

Professional identification usually requires assay testing or specialized tools — so if you’re near a known deposit and find unusually heavy, dark rock with metallic grains, it could be worth having it checked.

A Quick Request About Collecting

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Tips on Where to Look

Platinum is rare but not impossible to find. Here are some spots where you might get lucky with your search.

Placer Deposits

Check out streams and rivers. Platinum is heavy and sinks to the bottom of moving water. You’ll want to grab your pan and look in the same spots where you’d search for gold.

Focus on the bends of rivers where water slows down and heavier metals drop. The black sand areas are your best bet, and that’s where platinum particles often hide.

Sometimes, after a heavy rainfall washes away lighter materials, you might find platinum nuggets or flakes mixed in with other dense minerals that have been collecting there for thousands of years.

Ultramafic Rocks

Hunt around dark-colored rocks. Ultramafic rocks like serpentinite, which often have a greasy green look and feel, sometimes contain platinum. These rocks form from the Earth’s mantle and get pushed up to the surface.

Break open some samples and look for metallic specks. If you spot chromite (black, metallic mineral) in these rocks, that’s a good sign because platinum likes to hang out with chromite.

Old Mine Tailings

Don’t ignore old mining areas. The miners from back in the day missed stuff. Their old tailings (the leftover rock piles) might contain platinum they didn’t recognize or couldn’t extract with their tech.

Bring a metal detector that can pick up platinum – it responds differently than gold. Sift through these piles carefully, especially if the mine was known for nickel or copper, as platinum often shows up with these metals.

Weathered Outcrops

Explore weathered rock outcrops. When rocks break down from weather, heavier minerals like platinum concentrate near the bottom of slopes.

Look for rusty-colored areas where iron has oxidized because platinum sometimes exists alongside these iron-rich zones.

Some Great Places To Start

Here are some of the better places in the state to start looking for Platinum:

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Flint Ridge

Flint Ridge is a special area that connects Licking and Muskingum Counties in Ohio. This place is famous for its colorful flint that Native Americans used for tools. The ridge has unique rock layers formed about 300 million years ago when this area was under a shallow sea.

While most people visit to find flint, platinum can also be discovered here. Look for platinum in areas where the Vanport Limestone is exposed or weathered. The Nethers Farm section is a good spot to search, as visitors can explore old quarry pits throughout the area.

Many rockhounds check the soil around flint pieces, as platinum particles sometimes appear in the same locations. During spring and fall, erosion often reveals new material after heavy rains, making these seasons ideal for platinum hunting at Flint Ridge.

Chagrin River

The Chagrin River flows for 71 miles through northeastern Ohio before emptying into Lake Erie. Platinum seekers should focus on the river’s exposed shale formations, especially after heavy rains wash away topsoil.

The river’s course through different rock types creates natural “traps” where heavier minerals like platinum collect. South Chagrin Reservation offers good access points where Chagrin Shale is visible along the banks. The area near Chagrin Falls is particularly promising because the waterfall’s force has carved out deeper pools below, where heavy metals settle.

Local rockhounds have reported small platinum flakes in black sand deposits found in quiet eddies and inside bends of the river. Winter and early spring are best for searching, as lower water levels expose more riverbed. Bring a small pan to test sediments in areas where the current slows.

Clermont Area

Clermont County sits in the southwestern corner of Ohio with rolling hills and stream valleys. This area was shaped by glaciers that moved through Ohio thousands of years ago, bringing minerals from the north. Platinum particles can be found in stream sediments throughout the county, especially in glacial drift deposits.

The East Fork of the Little Miami River and its tributaries offer good hunting grounds. Elk Lick Valley has a history of precious metal discoveries since the 1800s, with platinum occasionally appearing alongside gold flakes.

Stonelick Creek is another hotspot where the water has cut through ancient glacial deposits. The creek’s gravel bars contain heavy minerals that collect in predictable patterns.

Wissel’s Run, a small tributary, has yielded interesting specimens in the past. The county’s unique combination of glacial history and active waterways makes it worth exploring for platinum enthusiasts.

French Creek

French Creek runs through Avon, as part of the Black River watershed, flowing to Lake Erie. This waterway has carved through layers of Cleveland Shale and other rock formations dating back millions of years. The creek’s path reveals interesting geology where platinum has been discovered.

Unlike other locations, French Creek’s platinum is often found in association with dark shale fragments rather than in typical sand deposits. The French Creek Reservation provides public access to several promising search areas.

Serious collectors look for platinum where the creek cuts through exposed bedrock. The reservation’s nature center displays samples of minerals found in the area, giving visitors an idea of what to search for. Professional geologists have studied this area because of its unusual mineral content.

Sandy Creek

Sandy Creek stretches 41 miles across northeastern Ohio before joining the Tuscarawas River near Bolivar. The creek flows through Columbiana, Carroll, Stark, and Tuscarawas counties, cutting through glacial deposits along the way.

Platinum particles have been found in the same gravel bars that contain placer gold. Areas near Malvern and Waynesburg have produced interesting specimens in the past. The deep floodplain deposits, sometimes over 200 feet thick, contain layers of ancient streambed materials where platinum can hide.

Look for black sand concentrations in places where the creek widens or changes direction suddenly. Old-timers recommend checking around large boulders where swirling water deposits heavier materials.

The kame formations south of Bayard also deserve attention from serious platinum hunters since these glacial sand deposits sometimes contain unexpected treasures.

Places Platinum has been found by County

After discussing our top picks, we wanted to discuss the other places on our list. Below is a list of the additional locations along with a breakdown of each place by county.

| County | Location |

| Seneca | Maple Grove Quarry |

| Ottawa | Clay Center |

| Ottawa | Genoa Quarry |

| Wood | Bowling Green Quarry |

| Various | Lake Erie Shoreline |

| Cuyahoga | Tinker’s Creek Gorge |

| Columbiana | Middle Fork of Little Beaver Creek |

| Clermont | Stonelick Creek |

| Clermont | Brushy Fork |