Kansas dirt might have more value than you think. While most folks pass by farm fields and rolling plains, tiny bits of platinum hide beneath the surface. Finding these precious metal specks takes time and patience.

We all hate wasting weekends on empty searches. Nothing hurts worse than coming home with an empty pan after hours under the hot sun. The feeling of finding nothing trip after trip can make anyone want to quit.

This guide cuts through the confusion about platinum hunting in Kansas. We’ll walk through exactly where to look based on geological facts, not wishful thinking.

How Platinum Forms Here

Platinum forms deep within Earth’s mantle, about 90-125 miles below the surface. This precious metal starts its journey when molten rock cools very slowly under extreme pressure.

Unlike gold, platinum rarely forms large nuggets. Instead, it typically appears as tiny grains mixed with other rocks. When ancient volcanoes erupt, they sometimes bring platinum-bearing rocks closer to the surface.

Over millions of years, weathering breaks down these rocks, and the heavy platinum particles get washed into streams and riverbeds.

Most platinum comes from places where parts of the mantle pushed up through the crust long ago. Miners often find platinum alongside nickel and copper deposits in igneous rocks.

Some platinum forms when meteor impacts create the perfect temperature and pressure conditions for these rare metals to crystallize.

Platinum Host Rocks

Platinum is a rare and valuable metal that occurs naturally in certain geological formations. These formations, often ultramafic and mafic igneous rocks, are significant hosts for platinum mineralization. Below is an overview of ten such rock types and geological settings associated with platinum deposits:

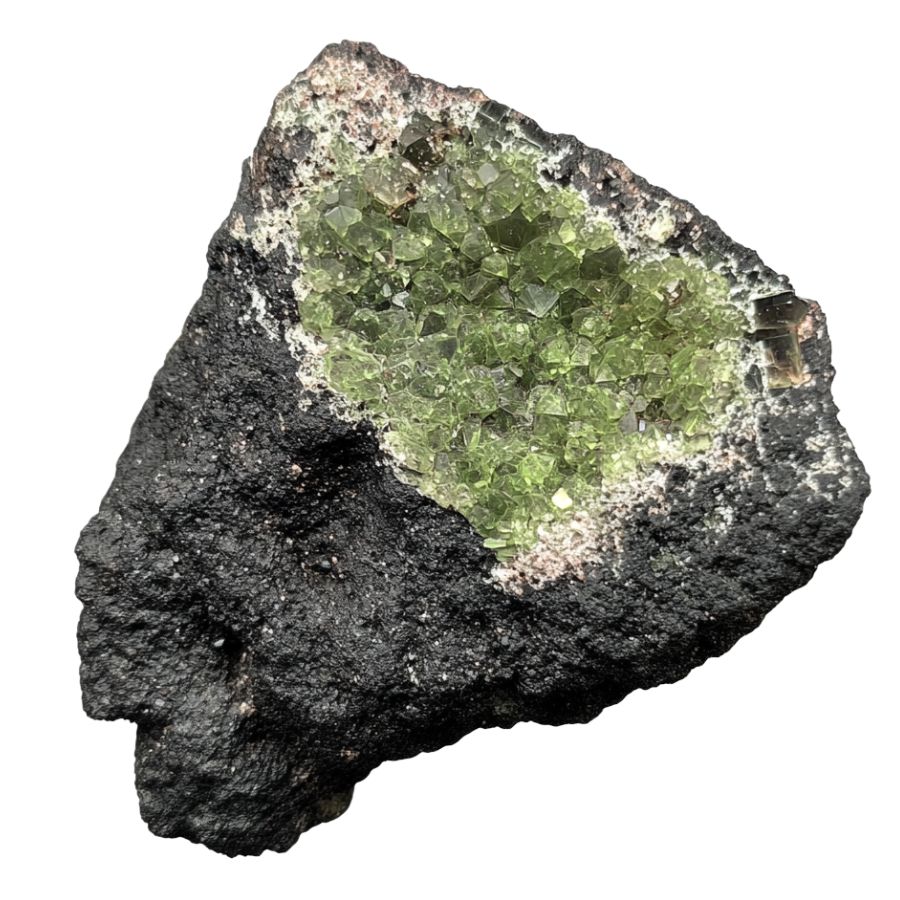

Peridotite

Peridotite is a green igneous rock that forms deep within the Earth’s mantle. Its striking color comes from its main mineral, olivine, with black specks from minerals like chromite or magnetite adding contrast. Unlike other similar rocks, peridotite contains less than 45% silica.

This special rock serves as a natural home for platinum. The precious metal hides inside peridotite as tiny grains, sometimes too small to see without a microscope.

Platinum in peridotite often teams up with other valuable metals like palladium, rhodium, and iridium. Miners search for areas where natural processes have concentrated these platinum grains into richer deposits.

When you see platinum jewelry, there’s a good chance the metal originally came from peridotite deep beneath the Earth’s surface.

Dunite

Dunite is an olive-green to yellowish-green rock with a speckled appearance. It has a coarse texture where you can see individual mineral grains. Unlike other similar rocks, dunite consists of more than 90% olivine, giving it a more uniform green color than peridotite or harzburgite.

Platinum loves to hide in dunite rocks, especially in areas with lots of chromite minerals. The platinum in dunite often appears as tiny metal flakes or as minerals mixed with arsenic compounds.

Over millions of years, as the magma cools and crystals grow, platinum gets caught between the olivine minerals. Some of the world’s most valuable platinum comes from dunite that formed over a billion years ago.

Harzburgite

Harzburgite displays a dark green to greenish-black color with a speckled appearance. It features olive-green olivine crystals mixed with darker orthopyroxene minerals. Unlike dunite, harzburgite contains significant amounts of orthopyroxene alongside olivine but has less clinopyroxene than other peridotite varieties.

The platinum in harzburgite tells an interesting story about Earth’s inner workings. This rock forms through a process called partial melting, which concentrates platinum in the remaining solid material.

As magma bubbles up through Earth’s mantle, harzburgite acts like a natural filter, sometimes collecting platinum along with other rare metals. Platinum hunters look for harzburgite that contains tiny sulfide minerals, as these often hold the precious metal.

The platinum in harzburgite is especially valuable because it forms under extreme conditions that are hard to reproduce in laboratories, making each deposit unique.

Pyroxenite

Pyroxenite comes in dark green, black, or light green colors with layered, banded, or veined patterns throughout the rock. It has a range of luster from dull to vitreous or even slightly metallic. Unlike peridotite varieties, pyroxenite contains mostly pyroxene minerals like augite and diopside, with little to no olivine.

Platinum finds a perfect home in pyroxenite rocks, often forming rich deposits that miners treasure. The special mineral makeup of pyroxenite creates ideal conditions for platinum to concentrate, especially along layer boundaries where different minerals meet.

When magma slowly cools to form pyroxenite, platinum particles get trapped in growing crystals or settle between layers. Sometimes, the platinum in pyroxenite appears as its own minerals like sperrylite, which contains platinum and arsenic. Other times, it hides inside sulfide minerals alongside copper and nickel.

Geologists use sophisticated tools to find these platinum-rich zones in pyroxenite, looking for subtle clues that indicate where the precious metal might be hiding.

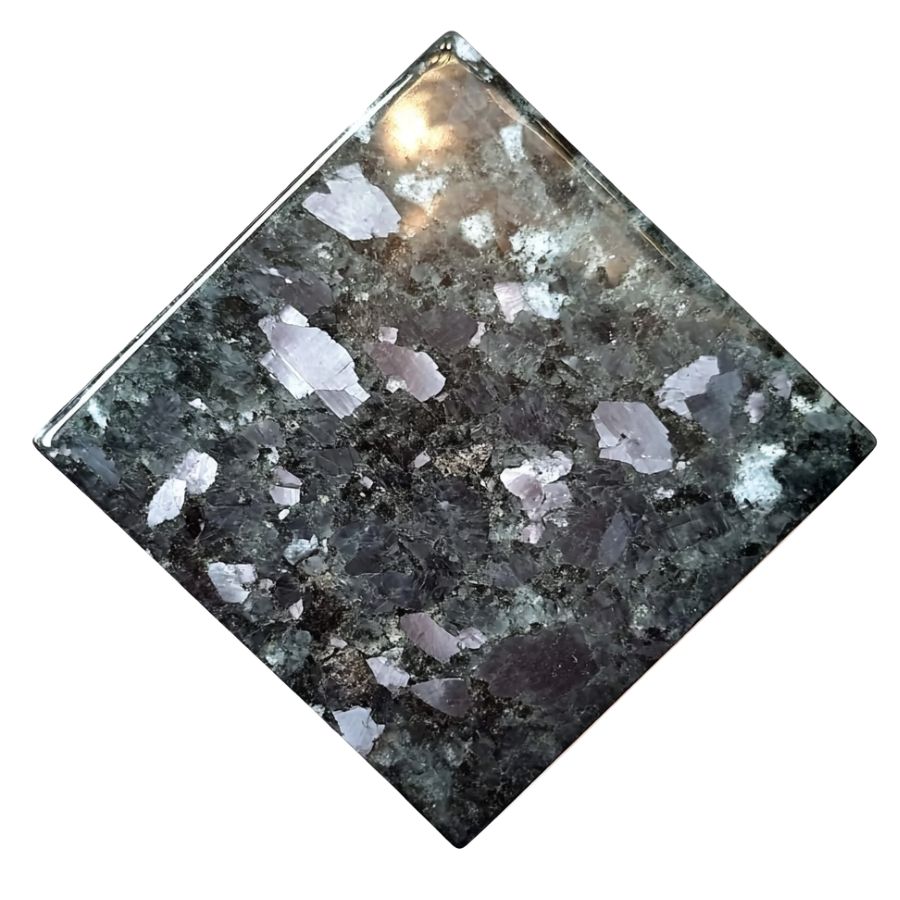

Norite

Norite is a dark gray to greenish-black rock with visible salt-and-pepper speckles. These speckles come from the light-colored plagioclase feldspar mixed with dark orthopyroxene minerals. The rock has a coarse texture where you can see individual crystals without a magnifying glass.

Platinum in norite typically appears alongside other valuable metals, creating treasure troves beneath the surface. Unlike in some other rocks, platinum in norite often forms during the cooling of magma chambers, when the metal concentrates in specific layers as the liquid rock solidifies.

The platinum minerals in norite can take various forms – sometimes as pure metal flakes, sometimes as compounds with sulfur or other elements. These differences affect how miners extract the platinum and how much the deposit is worth.

Gabbro

Gabbro is a dark-colored rock with visible crystals of white to gray feldspar mixed with black or dark green minerals. Its coarse texture comes from slow cooling deep underground, letting the crystals grow large enough to see easily. Unlike granite, which is light-colored with lots of quartz, gabbro is much darker and heavier.

When platinum appears in gabbro, it often creates some of the most valuable metal deposits on Earth. The platinum doesn’t spread evenly through the rock, instead, it concentrates in special zones that formed as the magma cooled and different minerals crystallized. These zones sometimes look like layers or bands running through the gabbro.

The platinum in gabbro usually teams up with metals like palladium, creating a natural alloy. Sometimes, it forms its own minerals with sulfur or arsenic. Because gabbro is so tough and resistant to weathering, mining platinum from it can be challenging but very rewarding.

Anorthosite

Anorthosite is a light-colored rock, usually white to light gray. Unlike most igneous rocks that contain various minerals, anorthosite is made up of more than 90% plagioclase feldspar, with very few dark minerals. This gives it a much lighter appearance than similar rocks like gabbro or norite.

The platinum in anorthosite systems often appears with copper and nickel minerals, forming complex patterns that geologists work hard to understand.

When studying anorthosite for platinum potential, scientists look for subtle color changes or mineral differences that might signal the presence of the valuable metal. The contrast between light anorthosite and the darker minerals that sometimes contain platinum makes these deposits particularly interesting.

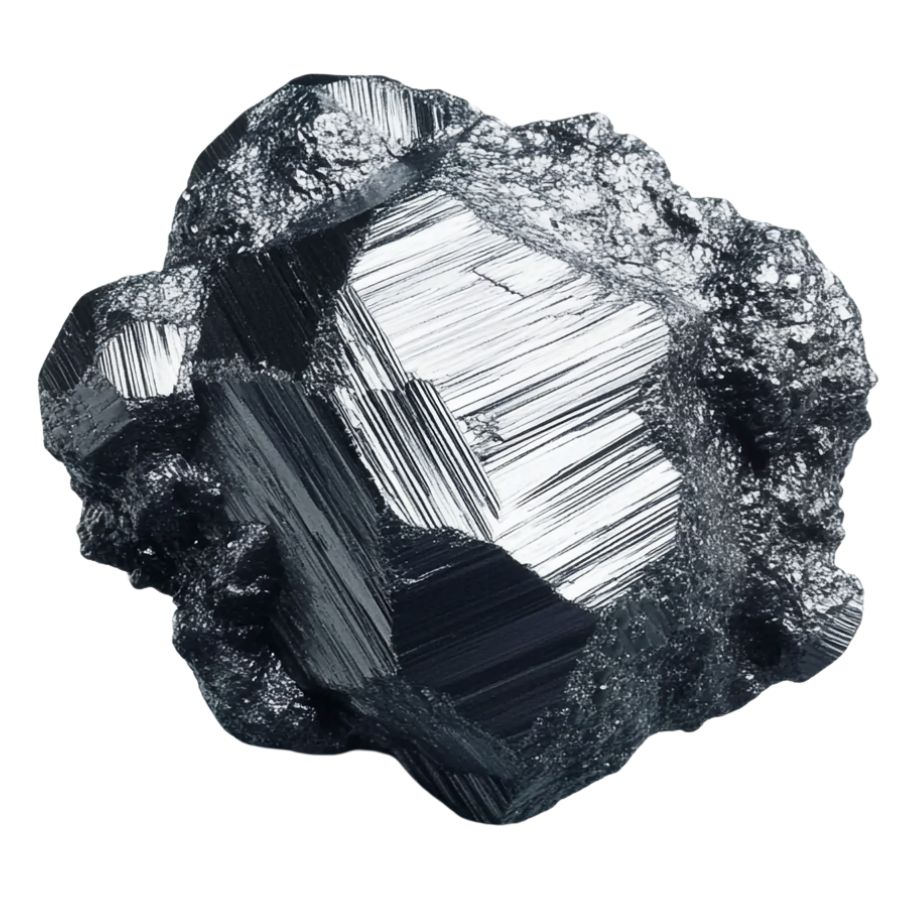

Chromitite

Chromitite is a dark, almost black mineral with a metallic to slightly greasy shine. When you look at it closely, it might have dark gray or brown-black tones. Unlike similar-looking minerals, chromitite forms in distinct masses or layers within certain rock types, especially in rocks related to ancient volcanoes.

Platinum in chromitite often appears as tiny grains nestled between the chromite crystals or as microscopic particles inside the crystals themselves. When geologists find thick layers of chromitite, they get excited about the platinum potential.

The relationship between chromium and platinum remains somewhat mysterious, but we know that the same geological processes that concentrate chromium often gather platinum too.

Some chromitite layers contain so much platinum that even though the metal is invisible to the naked eye, these rocks become some of the most valuable materials on Earth.

What Does Rough Platinum Look Like?

When found in the wild, rough platinum has distinctive qualities that separate it from other similar-looking minerals. Here’s how to spot it even if you’re not a rock expert.

Check for a Silvery-Gray or Steel Color

Raw platinum usually has a silvery-gray or steel-like appearance with a dull metallic luster. Unlike silver, it won’t tarnish or develop a blackened surface over time. It also lacks the brassy or yellowish tone of minerals like pyrite (fool’s gold).

Sometimes, native platinum may appear slightly darker due to natural coatings or mineral impurities. If you gently scratch the surface, you might expose a brighter metallic streak underneath — a good sign you’re on the right track.

Also, it won’t show rainbow flashes or colorful reflections like some other shiny minerals.

Look for Rounded, Worn Nugget Shapes

In nature, platinum typically appears as small nuggets, grains, or flattened flakes. These pieces often have smooth, rounded edges, especially if they’ve been tumbled in a stream or river. They can look a bit like dull silver pebbles — dense, worn, and irregular.

Crystalline platinum is extremely rare, so don’t expect sharp edges or well-defined shapes. Instead, look for odd but smoothed forms, like tiny clustered balls or slightly squished flakes.

Test the Surprising Heaviness

If you pick up a small piece and it feels unusually heavy for its size, that’s a strong clue. It’s denser than silver, lead, and even gold, giving it a distinct heft in your hand.

While it’s only slightly heavier than gold, it’s noticeably denser than most rocks or minerals you’ll come across. That weight, combined with color and shape, makes rough platinum easier to spot once you know what to look for.

What About Platinum Ore?

Platinum is often found in ore rather than as pure nuggets, especially in hard rock deposits. These ores usually come from ultramafic or mafic igneous rocks like peridotite, dunite, or chromitite. The rock might look dark, heavy, and unremarkable — but can contain microscopic grains of platinum group metals.

Visually, platinum ore doesn’t usually stand out. It’s often associated with other metals like nickel, copper, and iron, and may have a greenish or dark gray color with metallic flecks.

Professional identification usually requires assay testing or specialized tools — so if you’re near a known deposit and find unusually heavy, dark rock with metallic grains, it could be worth having it checked.

A Quick Request About Collecting

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Tips on Where to Look

Platinum is rare but not impossible to find. Here are some spots where you might get lucky with your search.

Placer Deposits

Check out streams and rivers. Platinum is heavy and sinks to the bottom of moving water. You’ll want to grab your pan and look in the same spots where you’d search for gold.

Focus on the bends of rivers where water slows down and heavier metals drop. The black sand areas are your best bet, and that’s where platinum particles often hide.

Sometimes, after a heavy rainfall washes away lighter materials, you might find platinum nuggets or flakes mixed in with other dense minerals that have been collecting there for thousands of years.

Ultramafic Rocks

Hunt around dark-colored rocks. Ultramafic rocks like serpentinite, which often have a greasy green look and feel, sometimes contain platinum. These rocks form from the Earth’s mantle and get pushed up to the surface.

Break open some samples and look for metallic specks. If you spot chromite (black, metallic mineral) in these rocks, that’s a good sign because platinum likes to hang out with chromite.

Old Mine Tailings

Don’t ignore old mining areas. The miners from back in the day missed stuff. Their old tailings (the leftover rock piles) might contain platinum they didn’t recognize or couldn’t extract with their tech.

Bring a metal detector that can pick up platinum – it responds differently than gold. Sift through these piles carefully, especially if the mine was known for nickel or copper, as platinum often shows up with these metals.

Weathered Outcrops

Explore weathered rock outcrops. When rocks break down from weather, heavier minerals like platinum concentrate near the bottom of slopes.

Look for rusty-colored areas where iron has oxidized because platinum sometimes exists alongside these iron-rich zones.

Some Great Places To Start

Here are some of the better places in the state to start looking for Platinum:

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Tri-State Mining District

The Tri-State Mining District in Cherokee County was a major mining area famous for lead and zinc production from the late 1800s to the mid-1900s. Towns like Galena, Treece, and Baxter Springs were important during the mining boom.

The ground here has Mississippian-age limestone and chert formations typical of Mississippi Valley-Type deposits. These unique formations create good conditions for finding various minerals.

For platinum, you should check the Treece Mining Area in southeastern Cherokee County, which has many old underground workings and waste piles. The Baxter Springs area along Spring River offers tailings and chat piles that could hold platinum.

Galena’s deep mining shafts and extensive underground tunnels provide another good spot for mineral hunting. Many rockhounds bring screens and pans to search through the leftover mining materials where small platinum pieces might be hiding.

Smoky Hill River

The Smoky Hill River starts in eastern Colorado and flows east through Kansas, cutting through the Smoky Hills region. This river exposes rock layers from the Cretaceous period, about 80-100 million years ago when the area was covered by an ancient sea.

Platinum seekers should focus on the river’s alluvial deposits along the banks, where the rushing water has concentrated heavy minerals over time. Ellis County offers promising spots where these deposits are accessible.

Another good location is near Junction City, about three miles southwest, where an abandoned quarry sits close to the river. The floodplain in this area has been studied for various minerals, including platinum.

River bends and areas after rapids are often hot spots for platinum particles as the slowing water drops heavier materials. Spring flooding often refreshes these deposits with new material each year.

Big Blue River

The Big Blue River runs about 359 miles from central Nebraska into northeastern Kansas, joining the Kansas River near Manhattan. Long-ago glaciers shaped this landscape, creating plains filled with sand, silt, and gravel deposits.

The river’s constant movement sorts materials by weight, often concentrating heavier minerals in specific spots. Platinum particles may be found alongside other minerals like agate, jasper, and petrified wood in the river’s sediments.

Blue Rapids is a key area for platinum hunters, with its unique formations and accessible riverbanks. Gravel bars here often contain various minerals worth searching through. Areas below Tuttle Creek Dam, northeast of Manhattan, are also worth exploring.

The dam’s outflow creates ideal conditions for mineral concentration. Places where smaller streams join the Big Blue River make excellent search locations too. Here, the changing water speed causes heavy minerals to drop to the riverbed.

Republican River

The Republican River flows through north-central Kansas, passing through Republic, Cloud, and Clay counties. This waterway begins in eastern Colorado and travels eastward until it meets the Smoky Hill River at Junction City.

Look for platinum along inside bends of the river where slower water allows heavy particles to settle. Areas with visible black sand layers are particularly promising, as these often contain concentrated heavy minerals.

River gravel bars exposed during low water periods offer accessible search locations. The junction points where tributaries flow into the main river create natural “sorting stations” for minerals.

After heavy rains, newly exposed materials along the banks may reveal platinum that was previously buried. Morning searches with low-angle sunlight often help spot metallic particles.

Rock City

Rock City in Ottawa County features over 200 massive round boulders spread across five acres. These “cannonball concretions” reach up to 27 feet across, creating a scene that looks like a city of giant stones. This special place has been named a National Natural Landmark because of its unusual geology.

The boulders formed about 100 million years ago during the Cretaceous Period when this area was near a shallow sea. Mineral-rich groundwater flowed through sand deposits, cementing the sand into solid rock balls. The surrounding softer sandstone wore away over millions of years, leaving the harder spheres exposed.

Platinum seekers should examine the bases of larger concretions where erosion has revealed inner structures. Broken pieces around the edges of the formations might also contain platinum that was trapped during formation.

Look for color changes or metallic shine that could indicate platinum presence. A hand lens can help spot tiny platinum pieces hidden in the sandstone matrix. Water seepage areas between formations can also concentrate minerals over time.

Places Platinum has been found by County

After discussing our top picks, we wanted to discuss the other places on our list. Below is a list of the additional locations along with a breakdown of each place by county.

| County | Location |

| Cherokee | Galena Mining Area |

| Russell | Wilson Lake |

| Chase | Flint Hills |

| Butler | Walnut River |

| Ellsworth | Carneiro |

| Mitchell | Blue Hills |

| Shawnee | Topeka |

| Barber | Medicine Lodge |

| Chautauqua | Chautauqua Hills |

| Gove | Castle Rock |