Platinum is pretty rare compared to gold, which makes finding it a real challenge for most folks. But that doesn’t mean it’s impossible.

I’ve spent years checking out different spots around Idaho. Some areas have better chances than others. The northern parts tend to show more promise, but you need to know the signs.

Water is usually your friend when hunting for platinum. Rivers and streams that cut through certain rock types often contain tiny platinum bits. The metal is heavy, so it tends to settle in places where water slows down. With some basic knowledge and patience, you might just find what you’re looking for.

How Platinum Forms Here

Platinum forms deep within Earth’s mantle, about 90-125 miles below the surface. This precious metal starts its journey when molten rock cools very slowly under extreme pressure.

Unlike gold, platinum rarely forms large nuggets. Instead, it typically appears as tiny grains mixed with other rocks. When ancient volcanoes erupt, they sometimes bring platinum-bearing rocks closer to the surface.

Over millions of years, weathering breaks down these rocks, and the heavy platinum particles get washed into streams and riverbeds.

Most platinum comes from places where parts of the mantle pushed up through the crust long ago. Miners often find platinum alongside nickel and copper deposits in igneous rocks.

Some platinum forms when meteor impacts create the perfect temperature and pressure conditions for these rare metals to crystallize.

Platinum Host Rocks

Platinum is a rare and valuable metal that occurs naturally in certain geological formations. These formations, often ultramafic and mafic igneous rocks, are significant hosts for platinum mineralization. Below is an overview of ten such rock types and geological settings associated with platinum deposits:

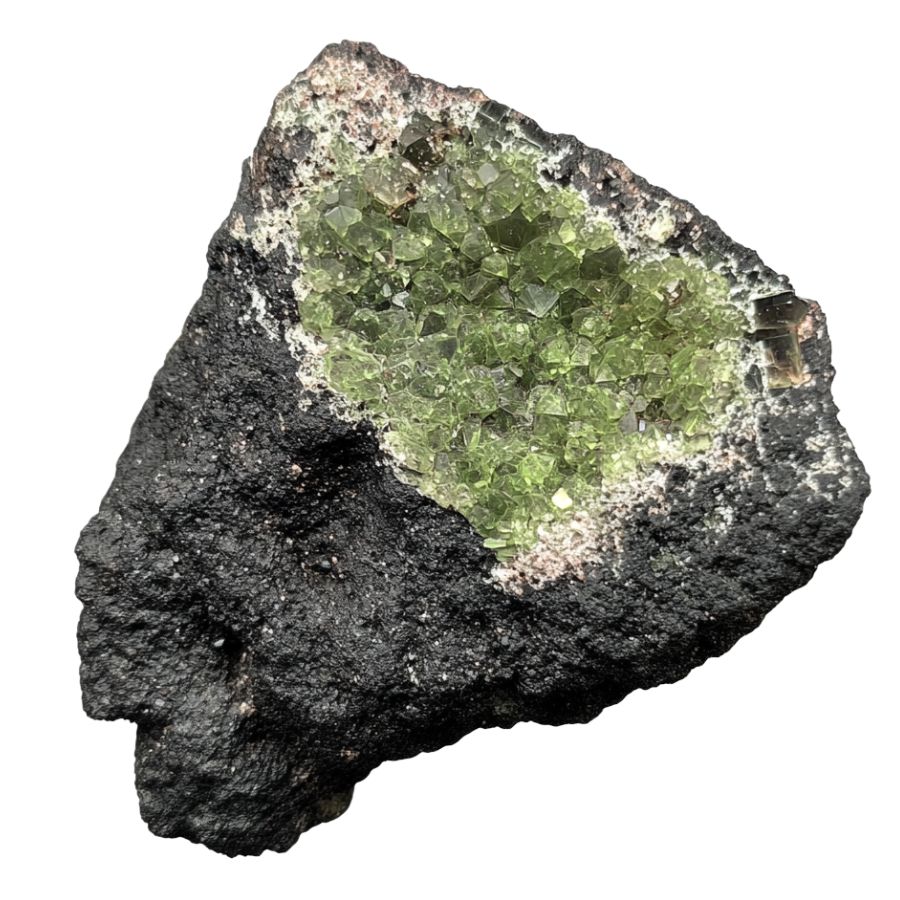

Peridotite

Peridotite is a green igneous rock that forms deep within the Earth’s mantle. Its striking color comes from its main mineral, olivine, with black specks from minerals like chromite or magnetite adding contrast. Unlike other similar rocks, peridotite contains less than 45% silica.

This special rock serves as a natural home for platinum. The precious metal hides inside peridotite as tiny grains, sometimes too small to see without a microscope.

Platinum in peridotite often teams up with other valuable metals like palladium, rhodium, and iridium. Miners search for areas where natural processes have concentrated these platinum grains into richer deposits.

When you see platinum jewelry, there’s a good chance the metal originally came from peridotite deep beneath the Earth’s surface.

Dunite

Dunite is an olive-green to yellowish-green rock with a speckled appearance. It has a coarse texture where you can see individual mineral grains. Unlike other similar rocks, dunite consists of more than 90% olivine, giving it a more uniform green color than peridotite or harzburgite.

Platinum loves to hide in dunite rocks, especially in areas with lots of chromite minerals. The platinum in dunite often appears as tiny metal flakes or as minerals mixed with arsenic compounds.

Over millions of years, as the magma cools and crystals grow, platinum gets caught between the olivine minerals. Some of the world’s most valuable platinum comes from dunite that formed over a billion years ago.

Harzburgite

Harzburgite displays a dark green to greenish-black color with a speckled appearance. It features olive-green olivine crystals mixed with darker orthopyroxene minerals. Unlike dunite, harzburgite contains significant amounts of orthopyroxene alongside olivine but has less clinopyroxene than other peridotite varieties.

The platinum in harzburgite tells an interesting story about Earth’s inner workings. This rock forms through a process called partial melting, which concentrates platinum in the remaining solid material.

As magma bubbles up through Earth’s mantle, harzburgite acts like a natural filter, sometimes collecting platinum along with other rare metals. Platinum hunters look for harzburgite that contains tiny sulfide minerals, as these often hold the precious metal.

The platinum in harzburgite is especially valuable because it forms under extreme conditions that are hard to reproduce in laboratories, making each deposit unique.

Pyroxenite

Pyroxenite comes in dark green, black, or light green colors with layered, banded, or veined patterns throughout the rock. It has a range of luster from dull to vitreous or even slightly metallic. Unlike peridotite varieties, pyroxenite contains mostly pyroxene minerals like augite and diopside, with little to no olivine.

Platinum finds a perfect home in pyroxenite rocks, often forming rich deposits that miners treasure. The special mineral makeup of pyroxenite creates ideal conditions for platinum to concentrate, especially along layer boundaries where different minerals meet.

When magma slowly cools to form pyroxenite, platinum particles get trapped in growing crystals or settle between layers. Sometimes, the platinum in pyroxenite appears as its own minerals like sperrylite, which contains platinum and arsenic. Other times, it hides inside sulfide minerals alongside copper and nickel.

Geologists use sophisticated tools to find these platinum-rich zones in pyroxenite, looking for subtle clues that indicate where the precious metal might be hiding.

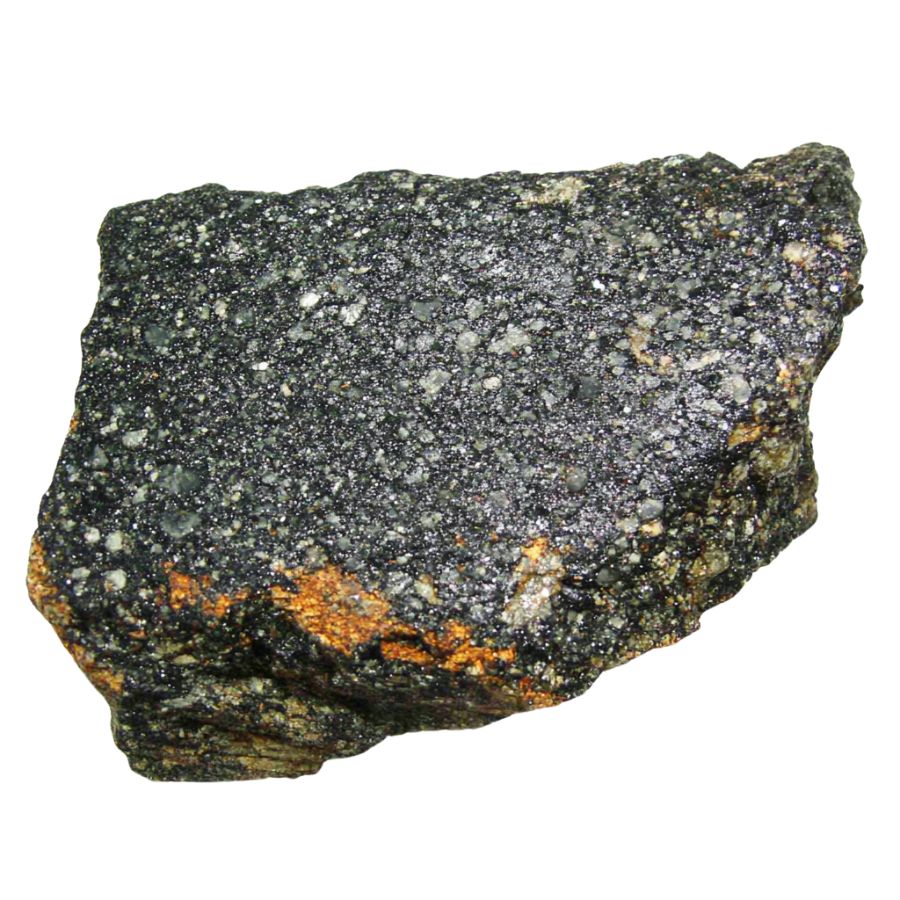

Norite

Norite is a dark gray to greenish-black rock with visible salt-and-pepper speckles. These speckles come from the light-colored plagioclase feldspar mixed with dark orthopyroxene minerals. The rock has a coarse texture where you can see individual crystals without a magnifying glass.

Platinum in norite typically appears alongside other valuable metals, creating treasure troves beneath the surface. Unlike in some other rocks, platinum in norite often forms during the cooling of magma chambers, when the metal concentrates in specific layers as the liquid rock solidifies.

The platinum minerals in norite can take various forms – sometimes as pure metal flakes, sometimes as compounds with sulfur or other elements. These differences affect how miners extract the platinum and how much the deposit is worth.

Gabbro

Gabbro is a dark-colored rock with visible crystals of white to gray feldspar mixed with black or dark green minerals. Its coarse texture comes from slow cooling deep underground, letting the crystals grow large enough to see easily. Unlike granite, which is light-colored with lots of quartz, gabbro is much darker and heavier.

When platinum appears in gabbro, it often creates some of the most valuable metal deposits on Earth. The platinum doesn’t spread evenly through the rock, instead, it concentrates in special zones that formed as the magma cooled and different minerals crystallized. These zones sometimes look like layers or bands running through the gabbro.

The platinum in gabbro usually teams up with metals like palladium, creating a natural alloy. Sometimes, it forms its own minerals with sulfur or arsenic. Because gabbro is so tough and resistant to weathering, mining platinum from it can be challenging but very rewarding.

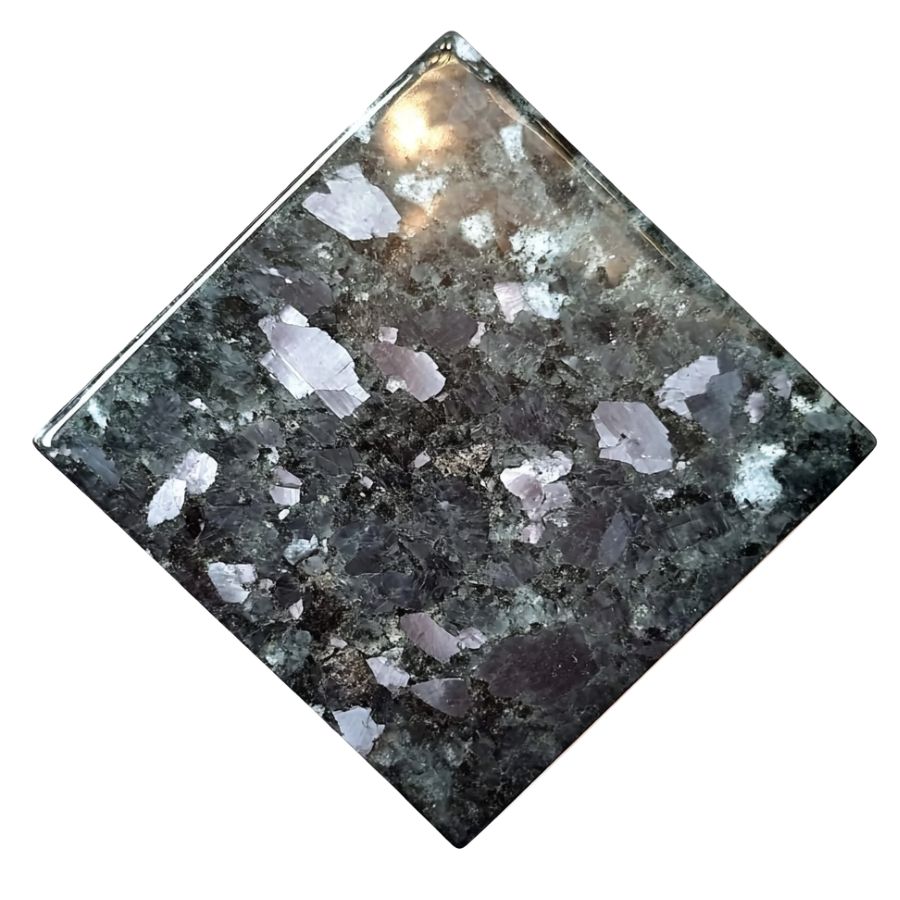

Anorthosite

Anorthosite is a light-colored rock, usually white to light gray. Unlike most igneous rocks that contain various minerals, anorthosite is made up of more than 90% plagioclase feldspar, with very few dark minerals. This gives it a much lighter appearance than similar rocks like gabbro or norite.

The platinum in anorthosite systems often appears with copper and nickel minerals, forming complex patterns that geologists work hard to understand.

When studying anorthosite for platinum potential, scientists look for subtle color changes or mineral differences that might signal the presence of the valuable metal. The contrast between light anorthosite and the darker minerals that sometimes contain platinum makes these deposits particularly interesting.

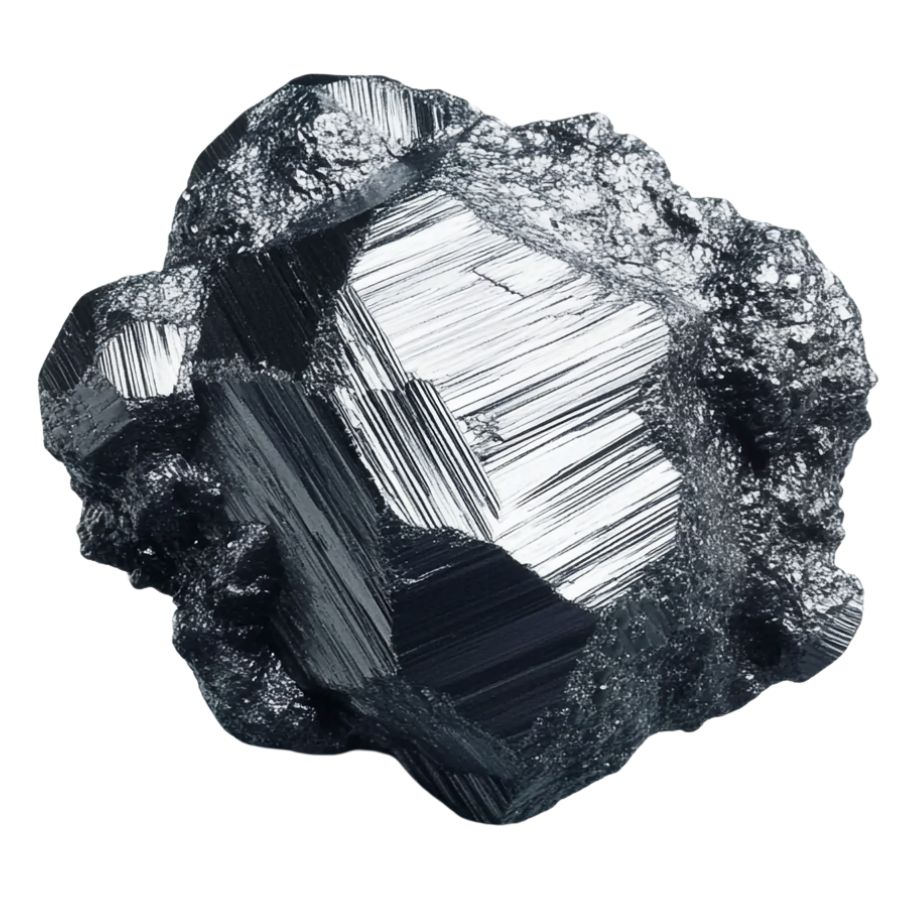

Chromitite

Chromitite is a dark, almost black mineral with a metallic to slightly greasy shine. When you look at it closely, it might have dark gray or brown-black tones. Unlike similar-looking minerals, chromitite forms in distinct masses or layers within certain rock types, especially in rocks related to ancient volcanoes.

Platinum in chromitite often appears as tiny grains nestled between the chromite crystals or as microscopic particles inside the crystals themselves. When geologists find thick layers of chromitite, they get excited about the platinum potential.

The relationship between chromium and platinum remains somewhat mysterious, but we know that the same geological processes that concentrate chromium often gather platinum too.

Some chromitite layers contain so much platinum that even though the metal is invisible to the naked eye, these rocks become some of the most valuable materials on Earth.

What Does Rough Platinum Look Like?

When found in the wild, rough platinum has distinctive qualities that separate it from other similar-looking minerals. Here’s how to spot it even if you’re not a rock expert.

Check for a Silvery-Gray or Steel Color

Raw platinum usually has a silvery-gray or steel-like appearance with a dull metallic luster. Unlike silver, it won’t tarnish or develop a blackened surface over time. It also lacks the brassy or yellowish tone of minerals like pyrite (fool’s gold).

Sometimes, native platinum may appear slightly darker due to natural coatings or mineral impurities. If you gently scratch the surface, you might expose a brighter metallic streak underneath — a good sign you’re on the right track.

Also, it won’t show rainbow flashes or colorful reflections like some other shiny minerals.

Look for Rounded, Worn Nugget Shapes

In nature, platinum typically appears as small nuggets, grains, or flattened flakes. These pieces often have smooth, rounded edges, especially if they’ve been tumbled in a stream or river. They can look a bit like dull silver pebbles — dense, worn, and irregular.

Crystalline platinum is extremely rare, so don’t expect sharp edges or well-defined shapes. Instead, look for odd but smoothed forms, like tiny clustered balls or slightly squished flakes.

Test the Surprising Heaviness

If you pick up a small piece and it feels unusually heavy for its size, that’s a strong clue. It’s denser than silver, lead, and even gold, giving it a distinct heft in your hand.

While it’s only slightly heavier than gold, it’s noticeably denser than most rocks or minerals you’ll come across. That weight, combined with color and shape, makes rough platinum easier to spot once you know what to look for.

What About Platinum Ore?

Platinum is often found in ore rather than as pure nuggets, especially in hard rock deposits. These ores usually come from ultramafic or mafic igneous rocks like peridotite, dunite, or chromitite. The rock might look dark, heavy, and unremarkable — but can contain microscopic grains of platinum group metals.

Visually, platinum ore doesn’t usually stand out. It’s often associated with other metals like nickel, copper, and iron, and may have a greenish or dark gray color with metallic flecks.

Professional identification usually requires assay testing or specialized tools — so if you’re near a known deposit and find unusually heavy, dark rock with metallic grains, it could be worth having it checked.

A Quick Request About Collecting

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Tips on Where to Look

Platinum is rare but not impossible to find. Here are some spots where you might get lucky with your search.

Placer Deposits

Check out streams and rivers. Platinum is heavy and sinks to the bottom of moving water. You’ll want to grab your pan and look in the same spots where you’d search for gold.

Focus on the bends of rivers where water slows down and heavier metals drop. The black sand areas are your best bet, and that’s where platinum particles often hide.

Sometimes, after a heavy rainfall washes away lighter materials, you might find platinum nuggets or flakes mixed in with other dense minerals that have been collecting there for thousands of years.

Ultramafic Rocks

Hunt around dark-colored rocks. Ultramafic rocks like serpentinite, which often have a greasy green look and feel, sometimes contain platinum. These rocks form from the Earth’s mantle and get pushed up to the surface.

Break open some samples and look for metallic specks. If you spot chromite (black, metallic mineral) in these rocks, that’s a good sign because platinum likes to hang out with chromite.

Old Mine Tailings

Don’t ignore old mining areas. The miners from back in the day missed stuff. Their old tailings (the leftover rock piles) might contain platinum they didn’t recognize or couldn’t extract with their tech.

Bring a metal detector that can pick up platinum – it responds differently than gold. Sift through these piles carefully, especially if the mine was known for nickel or copper, as platinum often shows up with these metals.

Weathered Outcrops

Explore weathered rock outcrops. When rocks break down from weather, heavier minerals like platinum concentrate near the bottom of slopes.

Look for rusty-colored areas where iron has oxidized because platinum sometimes exists alongside these iron-rich zones.

Some Great Places To Start

Here are some of the better places in the state to start looking for Platinum:

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Payette River

The Payette River flows through western Idaho, cutting through the Westview Mining District in Gem County. This river has been a mineral hunting ground since the 1850s, with the area near Pearl town being especially rich.

Black sand deposits in the river contain tiny platinum flakes, particularly where Squaw Creek and Willow Creek join the main river. These confluence points create natural traps for heavy minerals.

The river’s unique geology includes quartz diorite and granodiorite bedrock crossed by mineral-rich porphyry dikes. These dikes formed fissures containing arsenopyrite, pyrite, and other sulfide minerals that often accompany platinum.

Local prospectors focus on river bends where water slows down, especially after spring runoff refreshes the deposits. The Payette’s platinum particles are exceptionally fine, requiring careful panning techniques.

Valley Area

Valley County sits in central Idaho’s mountainous terrain, home to towns like McCall, Cascade, and Yellow Pine. The area is dominated by the massive Idaho Batholith, a 100-million-year-old granite formation.

Platinum occurs here in ultramafic rock formations, particularly in the historic Stibnite Mining District near Yellow Pine. This district supplied critical minerals during World War II and is currently undergoing revival with new mining operations.

Lick Creek Roadless Area northeast of McCall offers promising platinum prospects where ultramafic rocks are present. The area’s complex geology features multiple intrusion phases that concentrated platinum-group elements.

Bear Valley in the Payette National Forest is another platinum hotspot, known for unique mineral assemblages created by its geological history. The county’s streams fed by these mineral-rich zones are ideal for platinum panning, especially in late summer.

Snake River

The Snake River carves through southern Idaho’s volcanic corridor, shaped by the Yellowstone Hotspot’s ancient movement. The river’s course reveals dramatic basalt cliffs and unique geological layers.

Platinum particles in the Snake River are microscopic, typically found in black sand concentrates. The Minidoka area’s Sweetzer-Burroughs Dredge site in Blaine County has documented platinum occurrences mixed with other minerals.

Near Glenns Ferry in Elmore County, platinum-bearing placers occur in riverside terraces, where generations of miners have extracted black sands. The Twin Falls region’s Snake River Placers also yield platinum, concentrated by the river’s interaction with basalt formations.

The river’s platinum comes from eroded volcanic deposits that accumulated in slow-water zones. Successful hunters use specialized equipment with fine mesh screens since Snake River platinum is so small it can float away in conventional pans.

Rock Flat Placer

Rock Flat Placer sits in the Meadows Mining District near New Meadows in Adams County. This small deposit drains into Little Goose Creek Canyon and has produced an impressive variety of minerals throughout its history.

Platinum here appears alongside chromite, ilmenite, and magnetite in stream gravels. These heavy minerals concentrate in the lowest gravel layers just above bedrock. The platinum’s presence is linked to ultramafic rocks that formed deep within the Earth and were later exposed.

The site is unique for its combination of platinum with colorful garnets, zircon crystals, corundum, and even topaz. This unusual mineral assemblage makes the location special among Idaho’s mineral deposits.

Active stream channels within Little Goose Creek offer the best hunting grounds, particularly inside bends where water slows and drops heavier materials. The spring runoff season exposes fresh deposits annually.

Grand View Area

Grand View occupies 0.55 square miles in southwestern Idaho at 2,365 feet. The town developed around Dorsey Ferry, which once operated near the Bruneau River’s mouth. Today, it serves as an agricultural and mining community.

The Grand View Placer is the primary platinum source here, containing platinum grains among stream sediments rich in ilmenite, garnet, and martite. These deposits formed as water transported materials from the surrounding mountains.

The broader Bruneau-Grand View area features volcanic and sedimentary formations that contribute to its mineral diversity. Unusual volcanic glass sands in the region indicate its complex geological past.

Platinum particles here often have a distinctive reddish coating from iron-rich local soils. This characteristic helps experienced rockhounds identify Grand View platinum from other locations. The best collection spots appear along gravel bars following the spring flooding season.

Places Platinum has been found by County

After discussing our top picks, we wanted to discuss the other places on our list. Below is a list of the additional locations along with a breakdown of each place by county.

| County | Location |

| Boise | King Solomon Prospect |

| Bingham | Welch Bar |

| Blaine | Minidoka |

| Bonneville | Bilk Gulch Placer |

| Elmore | Rocky Bar |

| Idaho | Warren Mining District |

| Boise | Idaho City Mining District |

| Owyhee | Silver City Mining District |

| Custer | Bayhorse Mining District |

| Lemhi | Blackbird Mining District |

| Custer | Alder Creek Mining District |

| Lemhi | Parker Mountain |

| Owyhee | Succor Creek |

| Gem | Squaw Butte |

| Adams | Little Goose Creek Canyon |

| Adams | Seven Devils Mining District |

| Shoshone | Emerald Creek |

| Elmore | Atlanta |

| Custer | Bayhorse |

| Lemhi | Meyers Cove |