I’ve been searching for platinum in Alaska for over fifteen years now. The cold waters and rocky terrain make for tough work. But finding those tiny silvery bits makes it all worth it. I still remember my first small nugget – it wasn’t much, but it got me hooked.

The hunt for platinum differs from gold hunting. You need to look in different spots and know what signs to watch for. Black sand often means you’re getting close. Sometimes you’ll spend days finding nothing, then suddenly hit a good patch.

Most folks stick to the usual spots that everyone knows about. That’s fine for beginners. But the real treasures hide in less traveled areas. Over the years, I’ve mapped out secret locations where competition is scarce.

This article will take you beyond the common advice and show you where serious platinum hunters go when they want results.

How Platinum Forms Here

Platinum forms deep within Earth’s mantle, about 90-125 miles below the surface. This precious metal starts its journey when molten rock cools very slowly under extreme pressure.

Unlike gold, platinum rarely forms large nuggets. Instead, it typically appears as tiny grains mixed with other rocks. When ancient volcanoes erupt, they sometimes bring platinum-bearing rocks closer to the surface.

Over millions of years, weathering breaks down these rocks, and the heavy platinum particles get washed into streams and riverbeds.

Most platinum comes from places where parts of the mantle pushed up through the crust long ago. Miners often find platinum alongside nickel and copper deposits in igneous rocks.

Some platinum forms when meteor impacts create the perfect temperature and pressure conditions for these rare metals to crystallize.

Platinum Host Rocks

Platinum is a rare and valuable metal that occurs naturally in certain geological formations. These formations, often ultramafic and mafic igneous rocks, are significant hosts for platinum mineralization. Below is an overview of ten such rock types and geological settings associated with platinum deposits:

Peridotite

Peridotite is a green igneous rock that forms deep within the Earth’s mantle. Its striking color comes from its main mineral, olivine, with black specks from minerals like chromite or magnetite adding contrast. Unlike other similar rocks, peridotite contains less than 45% silica.

This special rock serves as a natural home for platinum. The precious metal hides inside peridotite as tiny grains, sometimes too small to see without a microscope.

Platinum in peridotite often teams up with other valuable metals like palladium, rhodium, and iridium. Miners search for areas where natural processes have concentrated these platinum grains into richer deposits.

When you see platinum jewelry, there’s a good chance the metal originally came from peridotite deep beneath the Earth’s surface.

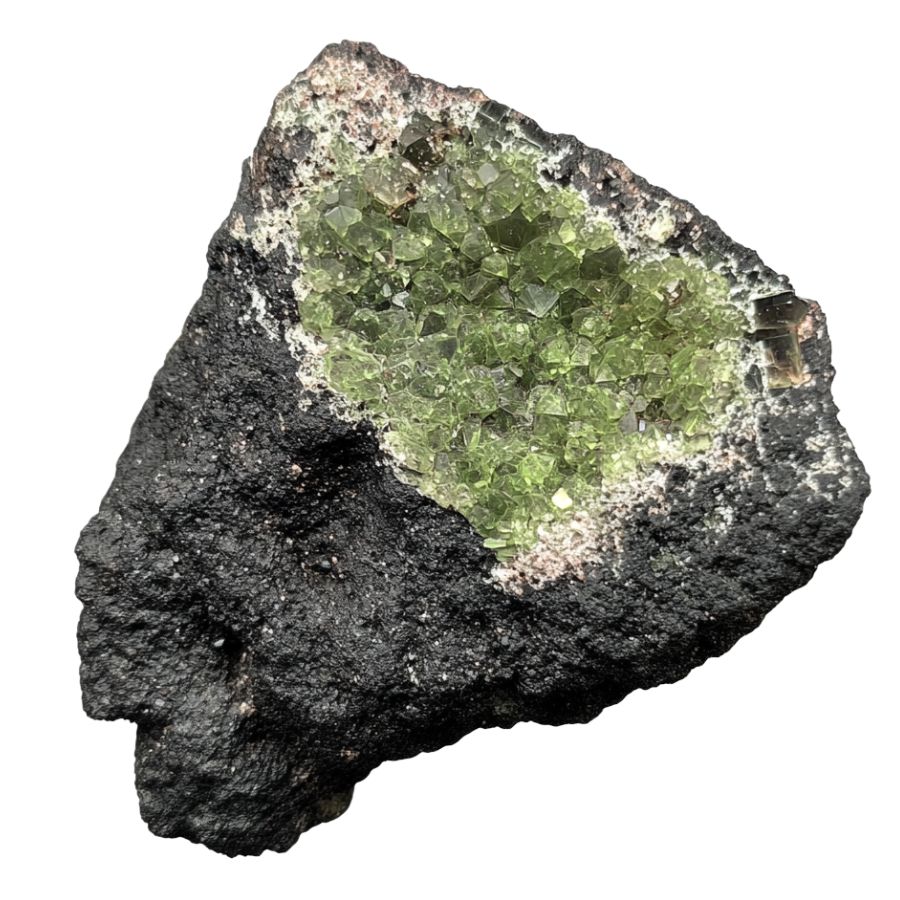

Dunite

Dunite is an olive-green to yellowish-green rock with a speckled appearance. It has a coarse texture where you can see individual mineral grains. Unlike other similar rocks, dunite consists of more than 90% olivine, giving it a more uniform green color than peridotite or harzburgite.

Platinum loves to hide in dunite rocks, especially in areas with lots of chromite minerals. The platinum in dunite often appears as tiny metal flakes or as minerals mixed with arsenic compounds.

Over millions of years, as the magma cools and crystals grow, platinum gets caught between the olivine minerals. Some of the world’s most valuable platinum comes from dunite that formed over a billion years ago.

Harzburgite

Harzburgite displays a dark green to greenish-black color with a speckled appearance. It features olive-green olivine crystals mixed with darker orthopyroxene minerals. Unlike dunite, harzburgite contains significant amounts of orthopyroxene alongside olivine but has less clinopyroxene than other peridotite varieties.

The platinum in harzburgite tells an interesting story about Earth’s inner workings. This rock forms through a process called partial melting, which concentrates platinum in the remaining solid material.

As magma bubbles up through Earth’s mantle, harzburgite acts like a natural filter, sometimes collecting platinum along with other rare metals. Platinum hunters look for harzburgite that contains tiny sulfide minerals, as these often hold the precious metal.

The platinum in harzburgite is especially valuable because it forms under extreme conditions that are hard to reproduce in laboratories, making each deposit unique.

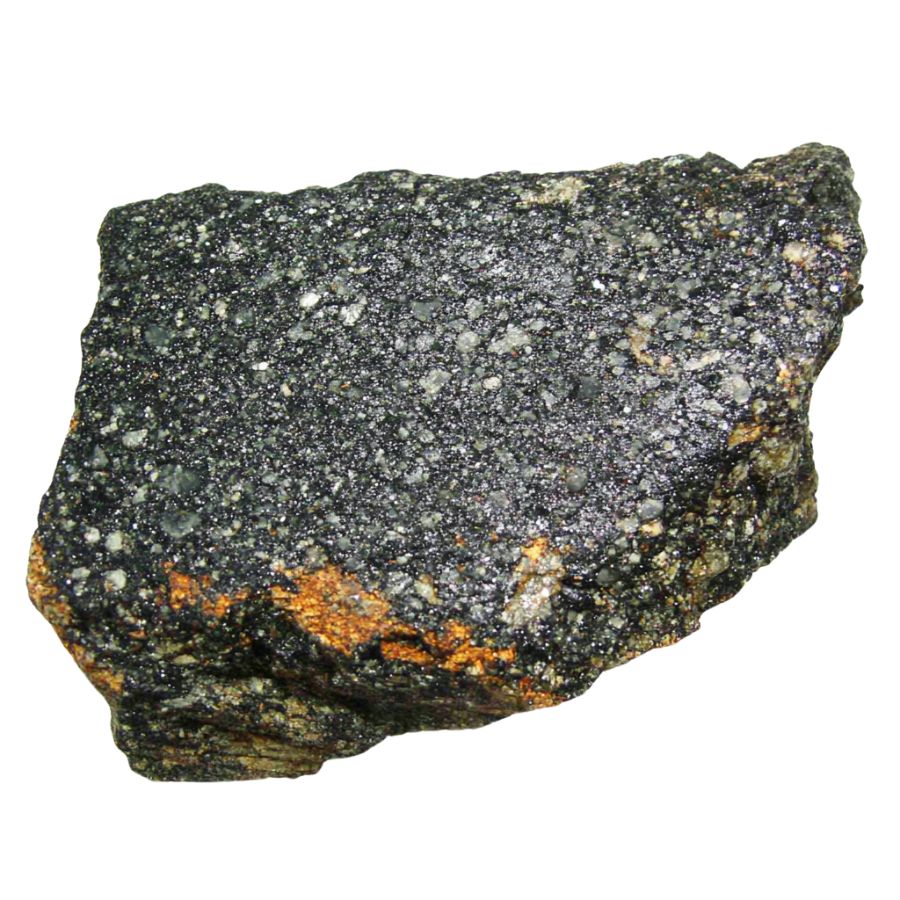

Pyroxenite

Pyroxenite comes in dark green, black, or light green colors with layered, banded, or veined patterns throughout the rock. It has a range of luster from dull to vitreous or even slightly metallic. Unlike peridotite varieties, pyroxenite contains mostly pyroxene minerals like augite and diopside, with little to no olivine.

Platinum finds a perfect home in pyroxenite rocks, often forming rich deposits that miners treasure. The special mineral makeup of pyroxenite creates ideal conditions for platinum to concentrate, especially along layer boundaries where different minerals meet.

When magma slowly cools to form pyroxenite, platinum particles get trapped in growing crystals or settle between layers. Sometimes, the platinum in pyroxenite appears as its own minerals like sperrylite, which contains platinum and arsenic. Other times, it hides inside sulfide minerals alongside copper and nickel.

Geologists use sophisticated tools to find these platinum-rich zones in pyroxenite, looking for subtle clues that indicate where the precious metal might be hiding.

Norite

Norite is a dark gray to greenish-black rock with visible salt-and-pepper speckles. These speckles come from the light-colored plagioclase feldspar mixed with dark orthopyroxene minerals. The rock has a coarse texture where you can see individual crystals without a magnifying glass.

Platinum in norite typically appears alongside other valuable metals, creating treasure troves beneath the surface. Unlike in some other rocks, platinum in norite often forms during the cooling of magma chambers, when the metal concentrates in specific layers as the liquid rock solidifies.

The platinum minerals in norite can take various forms – sometimes as pure metal flakes, sometimes as compounds with sulfur or other elements. These differences affect how miners extract the platinum and how much the deposit is worth.

Gabbro

Gabbro is a dark-colored rock with visible crystals of white to gray feldspar mixed with black or dark green minerals. Its coarse texture comes from slow cooling deep underground, letting the crystals grow large enough to see easily. Unlike granite, which is light-colored with lots of quartz, gabbro is much darker and heavier.

When platinum appears in gabbro, it often creates some of the most valuable metal deposits on Earth. The platinum doesn’t spread evenly through the rock, instead, it concentrates in special zones that formed as the magma cooled and different minerals crystallized. These zones sometimes look like layers or bands running through the gabbro.

The platinum in gabbro usually teams up with metals like palladium, creating a natural alloy. Sometimes, it forms its own minerals with sulfur or arsenic. Because gabbro is so tough and resistant to weathering, mining platinum from it can be challenging but very rewarding.

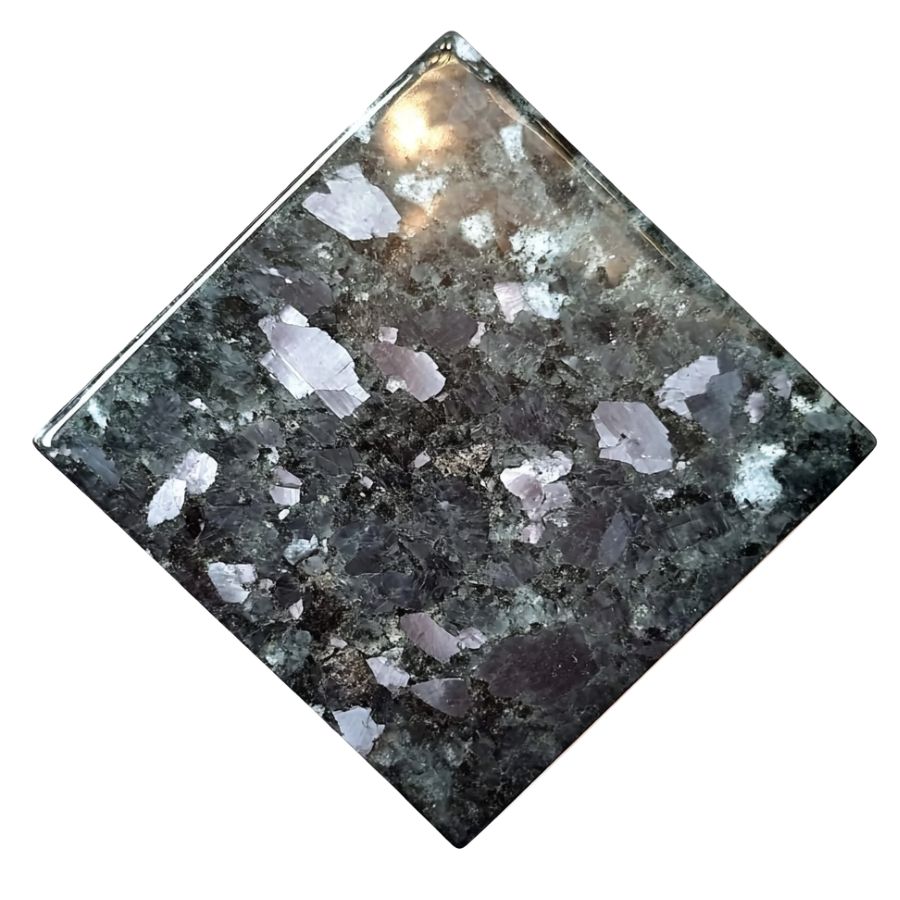

Anorthosite

Anorthosite is a light-colored rock, usually white to light gray. Unlike most igneous rocks that contain various minerals, anorthosite is made up of more than 90% plagioclase feldspar, with very few dark minerals. This gives it a much lighter appearance than similar rocks like gabbro or norite.

The platinum in anorthosite systems often appears with copper and nickel minerals, forming complex patterns that geologists work hard to understand.

When studying anorthosite for platinum potential, scientists look for subtle color changes or mineral differences that might signal the presence of the valuable metal. The contrast between light anorthosite and the darker minerals that sometimes contain platinum makes these deposits particularly interesting.

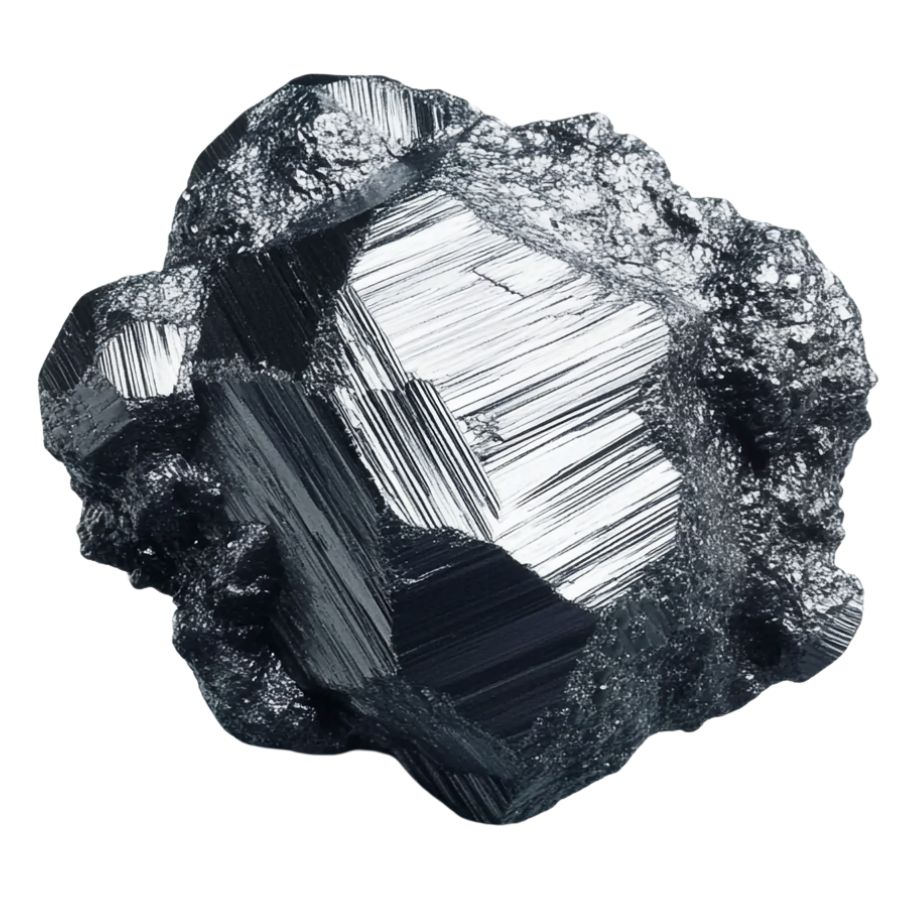

Chromitite

Chromitite is a dark, almost black mineral with a metallic to slightly greasy shine. When you look at it closely, it might have dark gray or brown-black tones. Unlike similar-looking minerals, chromitite forms in distinct masses or layers within certain rock types, especially in rocks related to ancient volcanoes.

Platinum in chromitite often appears as tiny grains nestled between the chromite crystals or as microscopic particles inside the crystals themselves. When geologists find thick layers of chromitite, they get excited about the platinum potential.

The relationship between chromium and platinum remains somewhat mysterious, but we know that the same geological processes that concentrate chromium often gather platinum too.

Some chromitite layers contain so much platinum that even though the metal is invisible to the naked eye, these rocks become some of the most valuable materials on Earth.

What Does Rough Platinum Look Like?

When found in the wild, rough platinum has distinctive qualities that separate it from other similar-looking minerals. Here’s how to spot it even if you’re not a rock expert.

Check for a Silvery-Gray or Steel Color

Raw platinum usually has a silvery-gray or steel-like appearance with a dull metallic luster. Unlike silver, it won’t tarnish or develop a blackened surface over time. It also lacks the brassy or yellowish tone of minerals like pyrite (fool’s gold).

Sometimes, native platinum may appear slightly darker due to natural coatings or mineral impurities. If you gently scratch the surface, you might expose a brighter metallic streak underneath — a good sign you’re on the right track.

Also, it won’t show rainbow flashes or colorful reflections like some other shiny minerals.

Look for Rounded, Worn Nugget Shapes

In nature, platinum typically appears as small nuggets, grains, or flattened flakes. These pieces often have smooth, rounded edges, especially if they’ve been tumbled in a stream or river. They can look a bit like dull silver pebbles — dense, worn, and irregular.

Crystalline platinum is extremely rare, so don’t expect sharp edges or well-defined shapes. Instead, look for odd but smoothed forms, like tiny clustered balls or slightly squished flakes.

Test the Surprising Heaviness

If you pick up a small piece and it feels unusually heavy for its size, that’s a strong clue. It’s denser than silver, lead, and even gold, giving it a distinct heft in your hand.

While it’s only slightly heavier than gold, it’s noticeably denser than most rocks or minerals you’ll come across. That weight, combined with color and shape, makes rough platinum easier to spot once you know what to look for.

What About Platinum Ore?

Platinum is often found in ore rather than as pure nuggets, especially in hard rock deposits. These ores usually come from ultramafic or mafic igneous rocks like peridotite, dunite, or chromitite. The rock might look dark, heavy, and unremarkable — but can contain microscopic grains of platinum group metals.

Visually, platinum ore doesn’t usually stand out. It’s often associated with other metals like nickel, copper, and iron, and may have a greenish or dark gray color with metallic flecks.

Professional identification usually requires assay testing or specialized tools — so if you’re near a known deposit and find unusually heavy, dark rock with metallic grains, it could be worth having it checked.

A Quick Request About Collecting

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Tips on Where to Look

Platinum is rare but not impossible to find. Here are some spots where you might get lucky with your search.

Placer Deposits

Check out streams and rivers. Platinum is heavy and sinks to the bottom of moving water. You’ll want to grab your pan and look in the same spots where you’d search for gold.

Focus on the bends of rivers where water slows down and heavier metals drop. The black sand areas are your best bet, and that’s where platinum particles often hide.

Sometimes, after a heavy rainfall washes away lighter materials, you might find platinum nuggets or flakes mixed in with other dense minerals that have been collecting there for thousands of years.

Ultramafic Rocks

Hunt around dark-colored rocks. Ultramafic rocks like serpentinite, which often have a greasy green look and feel, sometimes contain platinum. These rocks form from the Earth’s mantle and get pushed up to the surface.

Break open some samples and look for metallic specks. If you spot chromite (black, metallic mineral) in these rocks, that’s a good sign because platinum likes to hang out with chromite.

Old Mine Tailings

Don’t ignore old mining areas. The miners from back in the day missed stuff. Their old tailings (the leftover rock piles) might contain platinum they didn’t recognize or couldn’t extract with their tech.

Bring a metal detector that can pick up platinum – it responds differently than gold. Sift through these piles carefully, especially if the mine was known for nickel or copper, as platinum often shows up with these metals.

Weathered Outcrops

Explore weathered rock outcrops. When rocks break down from weather, heavier minerals like platinum concentrate near the bottom of slopes.

Look for rusty-colored areas where iron has oxidized because platinum sometimes exists alongside these iron-rich zones.

Some Great Places To Start

Here are some of the better places in the state to start looking for Platinum:

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Red Mountain

Red Mountain is a large mountain in the Goodnews Bay region of southwestern Alaska. This mountain has been a key platinum source in Alaska since the 1920s. The mountain is made up of dark-colored rocks called dunite and serpentinite that formed deep within the Earth. These special rocks contain platinum that slowly washes down into nearby streams when the mountain erodes.

Most platinum hunters focus on several creeks around Red Mountain. Fox Gulch, a small stream that flows into Platinum Creek, contains rich deposits in its lower gravel layers. Squirrel Creek also holds valuable platinum in its stream gravels.

Clara Creek on the northeast side of the mountain is another productive area where water and ancient glaciers have moved platinum from the mountain.

Besides platinum, Red Mountain also contains chromite, an important mineral used in making stainless steel. The area’s unique rock makeup has made it one of North America’s most significant platinum sources, with thousands of ounces recovered through the years.

Tukgahgo Mountain

Tukgahgo Mountain stands 4,675 feet tall in Alaska’s Takshanuk Mountains. Located about 16 miles southwest of Skagway, this mountain has an interesting mix of rocks that make it a target for platinum hunters.

Platinum at Tukgahgo Mountain is found in narrow quartz veins that cut through the mountain’s rocks. These veins form near the Tukgahgo Mountain fault, which runs southeast with a vertical drop of about 1,480 feet. The fault brings different rock types into contact, helping to create mineral-rich areas.

The best spot to look for platinum is on the northwest side of the mountain, where the fault and quartz veins are most accessible. Another promising area lies about 2,500 feet southwest of the summit, near Chilly Peak. Here, quartz veins contain various sulfide minerals that often accompany platinum.

Canyon Creek

Canyon Creek flows through Yentna Mining District. Miners have worked this creek since the early 1900s, looking for gold, platinum, and tin. The creek and its smaller branches, like Divide Creek and Long Creek, have seen many small mining operations over the years.

The stream gravels of Canyon Creek contain cobbles about six inches across, with some boulders reaching two feet in size. Under these gravels lies a pay streak varying from one to fifteen feet wide and two to eight feet deep.

Platinum appears as small grains in these gravels, often found alongside gold directly on the creek’s bedrock.

The best spots to search are in the creek’s headwaters, especially where acidic dikes cut through the slate rocks, and along Ramsdyke Creek on the northwest ridge.

Willow Creek

Willow Creek runs through the Talkeetna Mountains in south-central Alaska. Famous for its mining history, the area includes well-known spots like Hatcher Pass and Skyscraper Mountain.

A large mass of light-colored igneous rock called quartz diorite, formed 74 million years ago, creates the foundation for most gold deposits in the area. The Castle Mountain Fault runs through the district, influencing how minerals formed.

Platinum appears in serpentinite rocks within the Willow Creek district. Tests show these rocks contain up to 30 parts per billion of platinum along with high levels of chromium and nickel.

Treasure hunters should focus on the serpentinite bodies embedded in the Hatcher Pass schist formations. These are mainly found near the headwaters of Willow Creek and Fishhook Creek, especially in areas with green fuchsite-bearing schist and near major fault lines.

Bluestone River

Bluestone River is a 13-mile waterway in Alaska’s Seward Peninsula that flows north into Tuksuk Channel, about 12 miles southeast of Teller. The river starts where Gold Run and Right Fork Bluestone River meet. Flat-topped hills and a wide valley surround the river, with elevations between 400 and 1,200 feet.

Rock types in the area include mica and chlorite schists, limestone beds, and greenstone formed from altered mafic rocks. Small quartz veins cut through these rocks, especially in Gold Run Creek, one of the river’s tributaries. The region became famous for mining after gold was discovered in 1900.

Platinum hunters should focus on Gold Run Creek and its tributaries, where the river’s placer deposits contain various valuable minerals. The area’s special geology, with its mix of blueschist and greenschist rocks, helps concentrate platinum in the river gravels.

Places Platinum has been found by County

After discussing our top picks, we wanted to discuss the other places on our list. Below is a list of the additional locations along with a breakdown of each place by county.

| County | Location |

| Bethel Census Area | Salmon River |

| Bethel Census Area | Susie Mountain |

| Bethel Census Area | Hoholitna River |

| Bethel Census Area | Holitna River |

| Bethel Census Area | Upper Aniak River |

| Bethel Census Area | Kohiltna River |

| Bethel Census Area | Bear Creek Mine |

| Bethel Census Area | Boulder Creek Mine |

| Bethel Census Area | Dry Gulch Mine |

| Bethel Census Area | Kuskokwim Bay Occurrence |

| Bethel Census Area | Last Chance Creek Prospect |

| Bethel Census Area | McCann Creek Occurrence |

| Bethel Census Area | Dowry Creek Mine |

| Bethel Census Area | Smalls River Prospect |

| Denali Borough | California Creek Mine |

| Denali Borough | Moose Creek Mine |

| Haines Borough | Klukwan Fan Prospect |

| Haines Borough | Klukwan Prospect |

| Haines Borough | Chilly Peak |

| Kusilvak Census Area | Disappointment Creek Mine |

| Kusilvak Census Area | Wilson Creek Mine |

| Matanuska-Susitna Borough | Metal Creek |

| Matanuska-Susitna Borough | Alfred Creek |

| Matanuska-Susitna Borough | Cache Creek Area Mine |

| Matanuska-Susitna Borough | Kahiltna River |

| Matanuska-Susitna Borough | Lake Creek |

| Matanuska-Susitna Borough | Mills Creek |

| Matanuska-Susitna Borough | Poorman Creek |

| Matanuska-Susitna Borough | Ruby Creek |

| Matanuska-Susitna Borough | Twin Creek |

| Nome Census Area | Bear Gulch Mine |

| Nome Census Area | Dime Creek |

| Nome Census Area | Greenstone Creek Occurrence |

| Nome Census Area | Lower Sweepstakes Creek |

| Nome Census Area | Rube Creek Mine |

| Nome Census Area | Gold Run Mine |

| Northwest Arctic Borough | Bear Creek Mine |

| Northwest Arctic Borough | Quartz Creek; Jack Mine |

| Southeast Fairbanks Census Area | American Creek |

| Southeast Fairbanks Census Area | Lucky Gulch Mine |

| Southeast Fairbanks Census Area | East Fork Maclaren River Prospect |

| Valdez-Cordova Census Area | Nadina River Prospect |

| Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area | Anvik River Prospect |

| Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area | Woodchopper Creek Area Mine |

| Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area | Lake Creek Mine |