While the South Carolina state is better known for its gold deposits, many rockhounds are now turning their attention to its hidden opal treasures.

Finding opal isn’t easy, especially if you’re new to rockhounding. You could spend weeks searching in the wrong places without any luck. That’s why we’ve done the hard work for you.

We’ve talked to local collectors, visited multiple sites, and gathered information from geological surveys to bring you the most reliable spots for opal hunting in South Carolina.

These locations have been tested and proven to yield results, saving you time and frustration.

How Opal Forms Here

Opal forms here through a fascinating natural process. When water containing silica seeps into cracks and voids in rocks, it begins to evaporate, leaving behind tiny silica spheres.

Over time, these spheres stack in a grid-like pattern, creating opal. This process can take millions of years!

The colors in opal come from the way light refracts through the silica spheres. Different conditions in the ground, like the type of rock and the presence of other minerals, can affect the opal’s type, color, and quality.

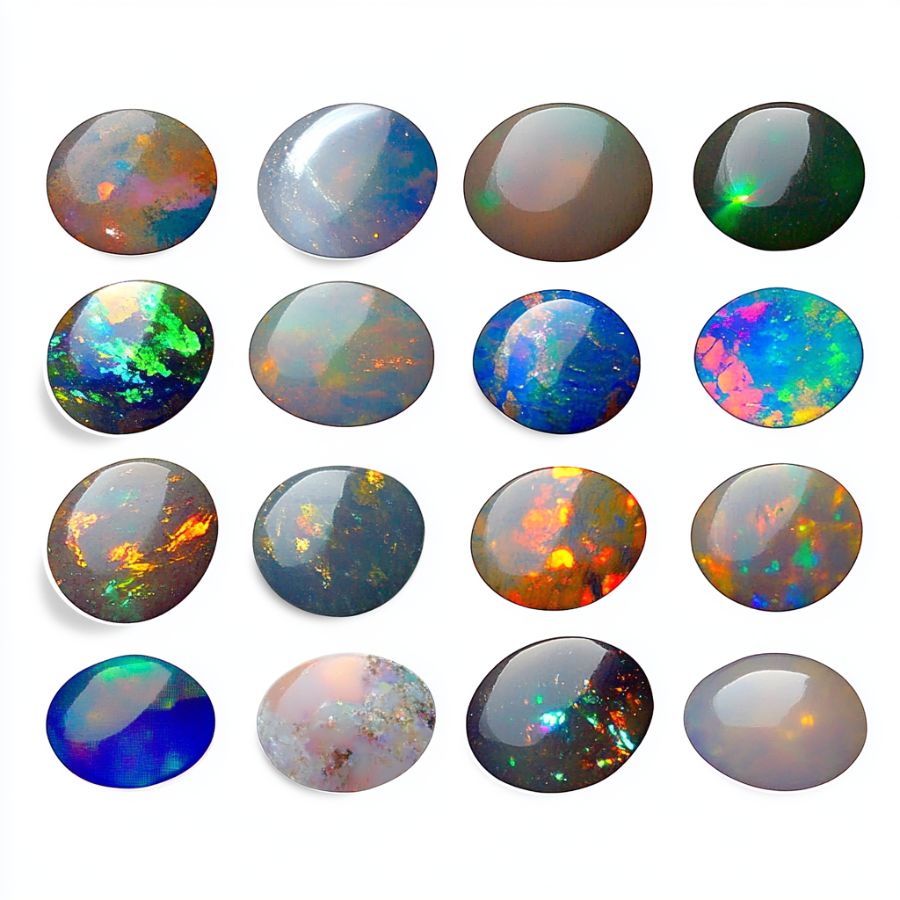

The Types Of Opal

There are several incredible types of Opal that can be found in the US as well as in our state. Each is uniquely beautiful and interesting including:

Common Opal

Common opal, also known as “potch,” stands out from other types of opal due to its lack of play-of-color, the iridescent display seen in precious opal. Instead, common opal features consistent, solid colors like white, pink, yellow, green, and blue.

It typically has a waxy to pearly luster and ranges from opaque to translucent. To identify common opal, look for its uniform color and absence of the shimmering color flashes found in precious opal.

Common opal forms under similar geological conditions as other opals, where silica-rich water seeps into rock cavities and slowly hardens over time. This process usually occurs in areas with volcanic activity or hot springs, where silica deposits are prevalent.

Fire Opal

Fire opal is known for its warm, vibrant colors, ranging from yellow and orange to deep red. Unlike precious opal, fire opal may or may not display the play-of-color, but its fiery body color makes it unique.

To identify fire opal, look for its bright, translucent to transparent appearance and the absence or presence of play-of-color within the warm hues.

Fire opal forms in volcanic regions where water rich in silica interacts with hot lava, filling cavities and fractures within the rock. Over time, the silica solution hardens, creating opal.

Visually, fire opal’s appeal lies in its vivid, flame-like colors that can be either uniform or exhibit internal flashes of color.

Boulder Opal

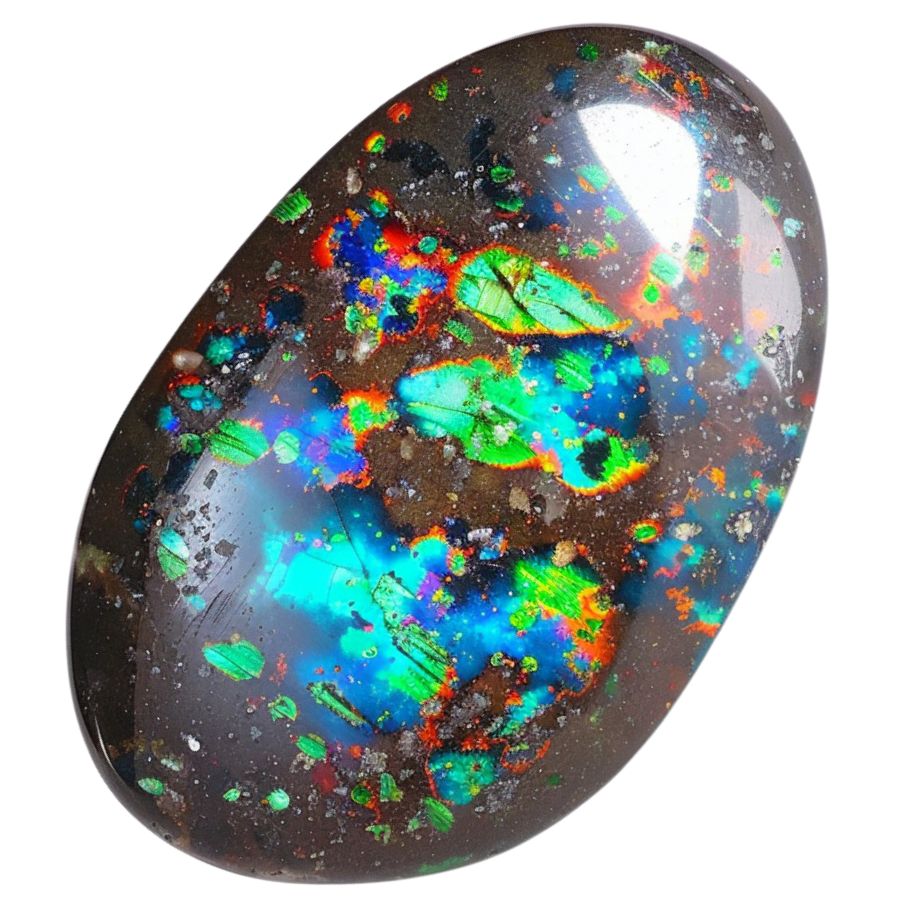

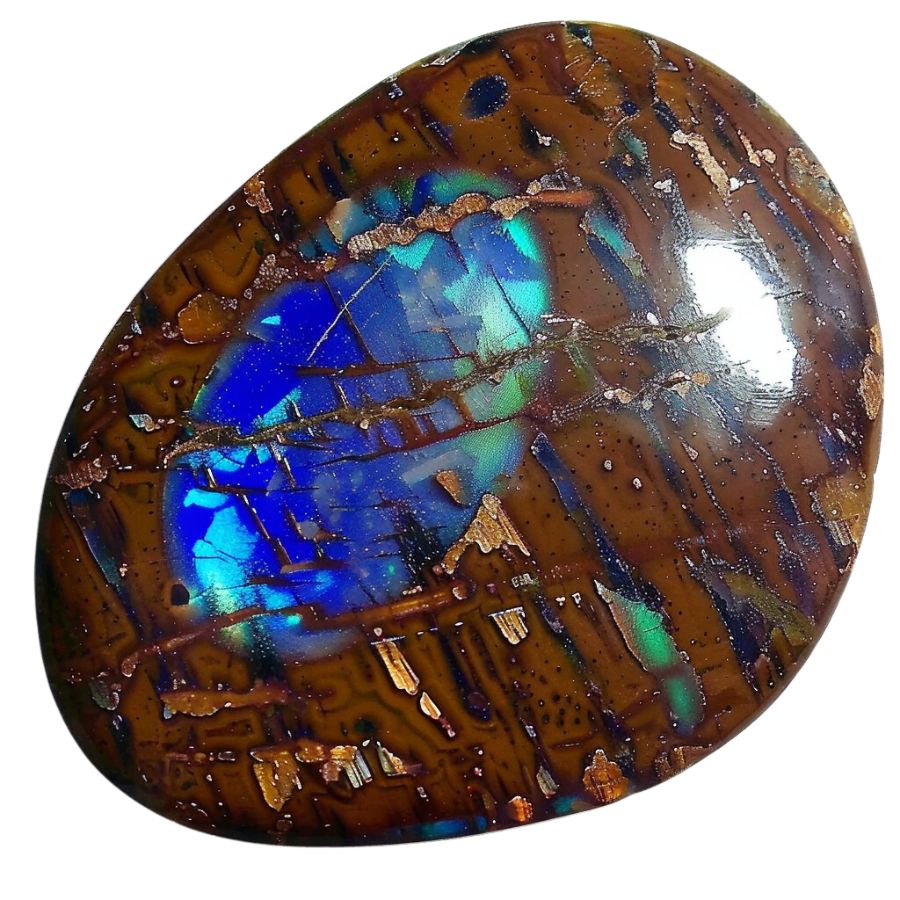

Boulder opal forms within the ironstone boulders of its host rock. Unlike other opals, boulder opal features precious opal veins intertwined with the natural rock, creating a beautiful contrast.

This opal is distinguished by its combination of colorful opal patches and the surrounding matrix, which can include ironstone or sandstone. To identify boulder opal, look for its vibrant play-of-color within the darker host rock, often showcasing brilliant blues, greens, and reds.

Boulder opal forms in sedimentary environments where silica-rich water infiltrates cracks and voids within ironstone or sandstone boulders. Over time, the silica hardens into opal, often creating thin seams or patches within the rock.

Hyalite Opal

Hyalite opal, also known as water opal, is a transparent to translucent type of opal that is distinctive for its glass-like appearance and lack of play-of-color. Unlike precious opal, which displays a rainbow-like iridescence.

You can identify hyalite opal by its clear to milky appearance, often with a slight green or blue fluorescence under UV light.

Hyalite opal forms in low-temperature hydrothermal environments, typically in volcanic regions. It precipitates from silica-rich fluids that fill cracks and voids in the host rock. This process can occur relatively quickly compared to other opal types.

Visually, hyalite opal resembles droplets of water or glass, often appearing as smooth, botryoidal (grape-like) formations. Its transparent nature makes it unique among opals, and its slight fluorescence adds to its allure.

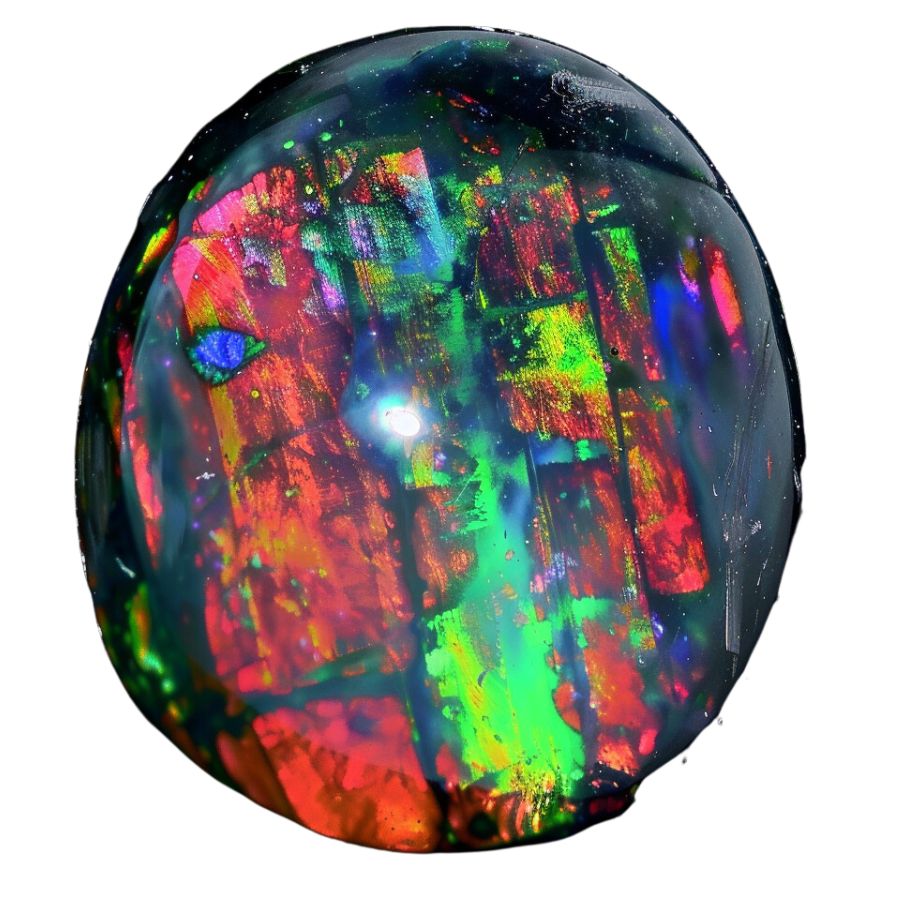

Black Opal

Black opal is a rare and highly prized variety known for its dark body tone, which enhances the vibrant play-of-color. Unlike other opals, black opal has a deep background color, ranging from dark gray to jet black, making the iridescent colors more striking.

To identify black opal, look for its intense, dark base color coupled with brilliant flashes of blues, greens, reds, and other hues.

The presence of iron and carbon contributes to its dark body color. In the United States, black opal is primarily found in the Virgin Valley of Nevada, known for its rich opal deposits.

Crystal Opal

Crystal opal is known for its transparent to translucent body, which allows the play-of-color to shine through brilliantly. Unlike common opal, which is opaque, crystal opal’s clear or semi-clear nature enhances its vibrant internal colors.

To identify crystal opal, look for its see-through quality combined with flashes of color that can include blues, greens, reds, and more.

Its unique transparency sets crystal opal apart, making it a favorite among gem enthusiasts and collectors for its ethereal beauty.

Wood Opal (Opalized Wood)

Opalized wood is a fascinating form of petrified wood where the organic material has been replaced by opal. Unlike other opals, opalized wood retains the original structure and texture of the wood, creating a unique blend of organic and mineral elements.

To identify opalized wood, look for its wood grain patterns and opalescent sheen, often displaying a range of colors from white and brown to vibrant reds and greens.

Opalized wood forms under specific conditions where wood is buried in silica-rich sediment. Over millions of years, the silica solution gradually replaces the organic wood material with opal, preserving the wood’s original structure in stunning detail.

Contra Luz Opal

Contra Luz opal reveals its vibrant play-of-color when illuminated from behind. Unlike other opals, which display their colors through surface reflection, contra luz opal’s brilliance comes to life with transmitted light.

To identify contra luz opal, hold the gem against a light source and observe the internal flashes of color, which can include vivid reds, blues, greens, and purples.

This opal forms in volcanic environments where silica-rich water infiltrates cracks and cavities in the host rock. As the water evaporates, it leaves behind silica deposits that eventually solidify into opal.

Visually, contra luz opal appears nearly clear or milky when viewed without backlighting. However, when backlit, it displays stunning, colorful patterns that seem to glow from within.

What Rough Opal Looks Like

When you’re out looking for rough opal on your own it’s important to know what you’re looking for.

DON'T MISS OUT ON ANY GREAT FINDS!

While you're out searching for Geodes you're going to find a lot of other interesting rocks and minerals along the way. The last thing you want to do is toss out something really interesting or valuable. It can be easy to misidentify things without a little guidance.

We've put together a fantastic field guide that makes identifying 140 of the most interesting and valuable rocks and minerals you will find REALLY EASY. It's simple to use, really durable, and will allow you to identify just about any rock and mineral you come across. Make sure you bring it along on your hunt!

This is what you need to look out for:

Look for exteriors like this

Look for play-of-color

Opal can display a range of colors, but what sets precious opal apart is its play-of-color—vivid flashes of multiple colors that change with the angle of light. Even in rough form, you might see hints of these colors peeking through.

Common opal lacks this feature and typically appears as a solid color like white, blue, or pink.

Check for a glassy or waxy luster

Opal often has a distinctive glassy or waxy luster. When you find a potential opal, examine its surface.

It should look shiny and smooth, almost like glass, even if it is still encased in a matrix or rough exterior.

Assess the density and weight

Opal is generally lighter than rocks of a similar size. When you pick up a piece of rough opal, it should feel lighter than expected.

Additionally, opal is relatively soft, with a Mohs hardness of 5.5 to 6.5, so it can be scratched more easily than quartz or other harder minerals.

A Quick Request About Collecting

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Tips on where to look

Once you get to the places we have listed below there are some things you should keep in mind when you’re searching:

Search in Sedimentary Rock Formations

Opal can also form in sedimentary rock formations where silica deposits have accumulated over time.

Focus on areas with ancient lake beds or clay deposits, as these environments are conducive to opal formation.

Check Dry Creek Beds and Gullies

Dry creek beds and gullies can be excellent places to find opal, as water flow can erode and expose opal-bearing rocks.

Look for exposed rock and gravel in these areas, especially after rainfall or seasonal flooding.

Investigate Old Mining Sites

Abandoned or historical mining sites can be rich in opal and other minerals. These areas often have tailings and discarded rock that may still contain opal.

Always seek permission if the land is privately owned and follow safety guidelines.

Look for Indicator Minerals

Certain minerals can indicate the presence of opal. Look for rocks and soil containing ironstone, sandstone, or clay, as these materials often coexist with opal deposits.

Additionally, finding quartz or chalcedony can suggest nearby opal.

The types of Opal can you find around the state

The type of Opal mostly found in South Carolina is Hyalite. This variety of opal is characterized by its colorless, glass-like appearance and is classified as Opal-AN, meaning it has a unique amorphous structure without the silica spheres typically found in precious opals.

Hyalite does not exhibit the play-of-color that many other opals do but can display a striking green fluorescence under ultraviolet light due to its uranium content.

Hyalite opal can be discovered in various locations across the United States, including South Carolina.

While it may not be as visually captivating as precious opals, hyalite’s distinctive properties and fluorescence make it a fascinating specimen for collectors and gem enthusiasts alike

Some Great Places To Start

Here are some of the better places to start looking for Opal in South Carolina:

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Lake Wateree Shoreline

Lake Wateree is a large reservoir located 30 miles northeast of Columbia, South Carolina. The lake covers nearly 14,000 acres and has 181 miles of shoreline across various counties. You can easily reach it using Interstate 77 and SC 97.

The lake was created in 1919 by damming the Wateree River, making it one of South Carolina’s oldest man-made lakes. Its shallow waters, with an average depth of 23 feet, create perfect conditions along the shoreline for rockhounding.

The best spots to look for opals are near fallen trees and rocky outcrops along the shoreline. The areas around Mineral Spring and Liberty Hill Historic District are known to be good spots for finding interesting stones.

The lake’s mix of sedimentary rocks, quartz, and chert makes it an interesting place for rock collectors. Many rockhounds have found success searching after rainstorms when the water washes new material onto the shore.

Lynches River

Lynches River flows through Kershaw County in South Carolina’s Piedmont region. The river stretches from the northern part of the state and joins the larger Pee Dee River.

The river’s geology is special because it cuts through different rock types. In the upper basin near Pageland and Jefferson, you’ll find metamorphic rocks that sometimes contain gemstones.

The middle section of the river passes through the sand hills, which are actually ancient beach dunes from when this area was an ocean shoreline. The best places to look for opals are in the upper basin near Pageland.

This area was once busy with gold mining, and the same geological conditions that created gold deposits also made it possible for opals to form. The area around Bethune and McBee is also worth checking because of its unique sand hills geology.

Lancaster area

The Lancaster area sits in northwest South Carolina, close to the North Carolina border. The area’s landscape tells a story of ancient geological processes that created rich mineral deposits.

The region stands out for its special rock formations called pegmatites. These rocks formed long ago when hot magma slowly cooled underground, creating large crystal formations.

The best spots to look for opals are around exposed pegmatite formations. Many rockhounds have found success searching the weathered outcrops where these rocks break through the surface.

The area has also given up other precious stones like aquamarine, beryl, and garnets. Local creeks and streams that cut through the pegmatite zones are good places to search, as water helps expose minerals.

Fairfield area

Fairfield area is in the lower Piedmont area of South Carolina, between the Broad and Wateree Rivers. This area is full of rolling hills and flat plains, making it perfect for rock and mineral hunting.

The area’s rich geological history has created various spots where opals can be found. Stream beds in the county often reveal interesting finds, especially after heavy rains wash away top soil.

Besides opals, the area is known for other valuable stones like aquamarine, sapphire, and quartz. The mix of different rock types in Fairfield makes it special for gem hunters.

The best time to search is after rainfall when stones are more visible. The exposed rocks near stream beds and eroded hillsides are good starting points for finding opals.

Haile Mine Region

The Haile Mine Region sits in southern Lancaster County, South Carolina, close to the town of Kershaw. This area is part of the Carolina Slate Belt, a special geological zone that runs from Georgia to Virginia.

The area’s rocks were formed during the Neoproterozoic to lower Cambrian periods. These rocks have changed over time due to heat and pressure. The ground here has unique features like silicified sediments and weathered rock layers called saprolite.

Opals in this region are found in areas where hot water once moved through the rocks, creating spaces where the gems could form. The best places to look are in the silicified zones, which can be as thin as one meter or as thick as 100 meters.

The area’s mix of old metamorphic rocks and coastal plain sediments makes it different from other mining regions in the Southeast.

Places Opal has been found by county

After discussing our top picks, we wanted to discuss the other places on our list. Below is a list of the additional locations where we have succeeded, along with a breakdown of each place by county.

| County | Location |

| Abbeville | Diamond Hill Mine |

| Edgefield | Graves Mountain |

| Anderson | Hogg Mine |

| Greenville | Paris Mountain State Park |

| Spartanburg | Pacolet River |

| York | Kings Mountain State Park |

| Cherokee | Broad River Basin |

| McCormick | Baker Creek State Park |

| Edgefield | Stevens Creek |

| Saluda | Little Saluda River |

| Newberry | Enoree River |

| Richland | Congaree River Beds |

| Lexington | Saluda River Banks |

| Orangeburg | North Fork Edisto River |

| Calhoun | Congaree Creek |

| Sumter | Wateree River |

| Clarendon | Lake Marion Shores |

| Williamsburg | Black River Area |

| Georgetown | Waccamaw River |

| Horry | Little Pee Dee River |

| Marion | Great Pee Dee River |

| Dillon | Lumber River |

| Florence | Lynches River |

| Darlington | Black Creek |

| Chesterfield | Pee Dee River |

| Marlboro | Bennettsville Quarries |

| Lee | Lynches River |

| Bamberg | Little Salkehatchie River |

| Barnwell | Savannah River |

| Allendale | Lower Three Runs Creek |

| Hampton | Salkehatchie River |

| Jasper | Coosawhatchie River |

| Beaufort | Broad River |

| Charleston | Ashley River |

| Oconee | Chattooga River |

| Edgefield | Stevens Creek |

| Spartanburg | Pacolet River |