Vermont’s green mountains and rocky terrain make it a good spot for rock hunters. People have been digging for cool stones here for years. Labradorite is one of those neat finds that gets rock lovers excited.

I’ve spent many weekends hunting for rocks in Vermont. Sometimes I come home empty-handed. Other times, my pockets are full of amazing stones. The thrill of finding that first piece of shiny labradorite is hard to beat.

This article will point you to some Vermont areas where labradorite might be waiting. You don’t need to be an expert to find these stones. Even beginners can get lucky with a little patience.

How Labradorite Forms Here

Labradorite forms deep underground when magma slowly cools and crystallizes. The process happens when different minerals separate while cooling, creating thin layers stacked on top of each other. These layers have slightly different chemical makeups, usually about 1 micron thick.

When light hits these layers, it creates that stunning blue-green flash we love, called labradorescence. The stone starts out as a mix of calcium, sodium, aluminum, and silicate minerals.

As it cools, these minerals organize themselves into this layered pattern, which happens most often in places where magma intrudes into the surrounding rock. It’s like nature’s own light show, frozen in stone.

Types of Labradorite

Labradorite comes in several distinct varieties. Each type exhibits special qualities that make it sought after by collectors.

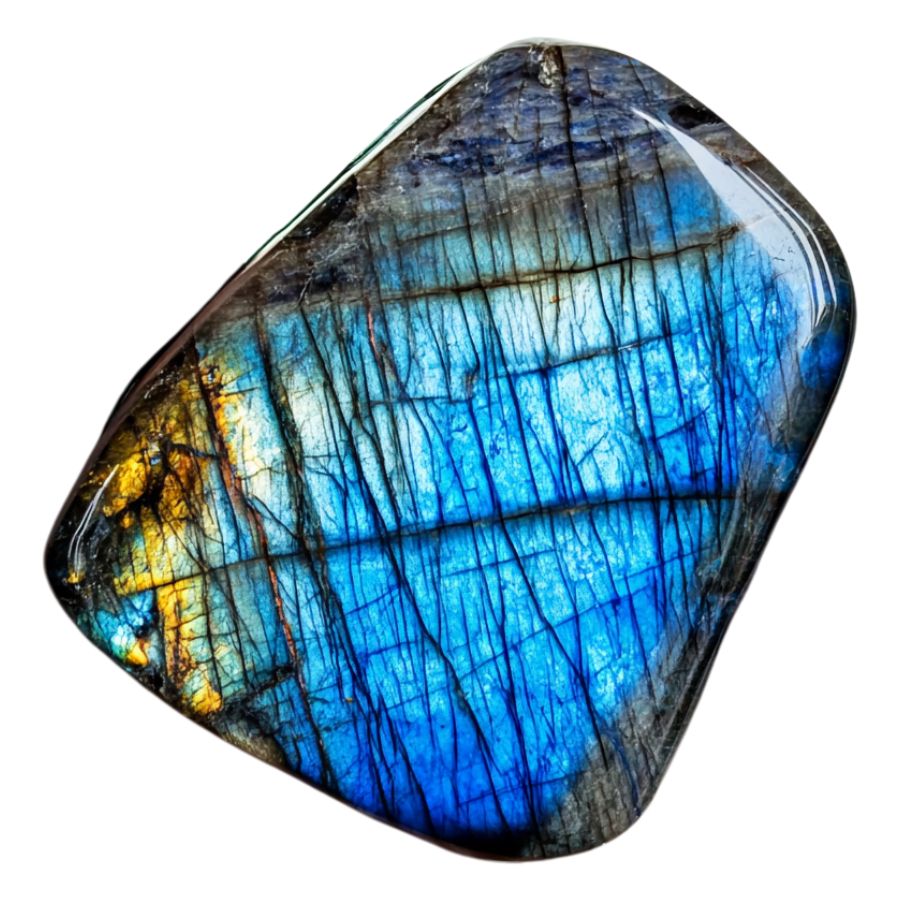

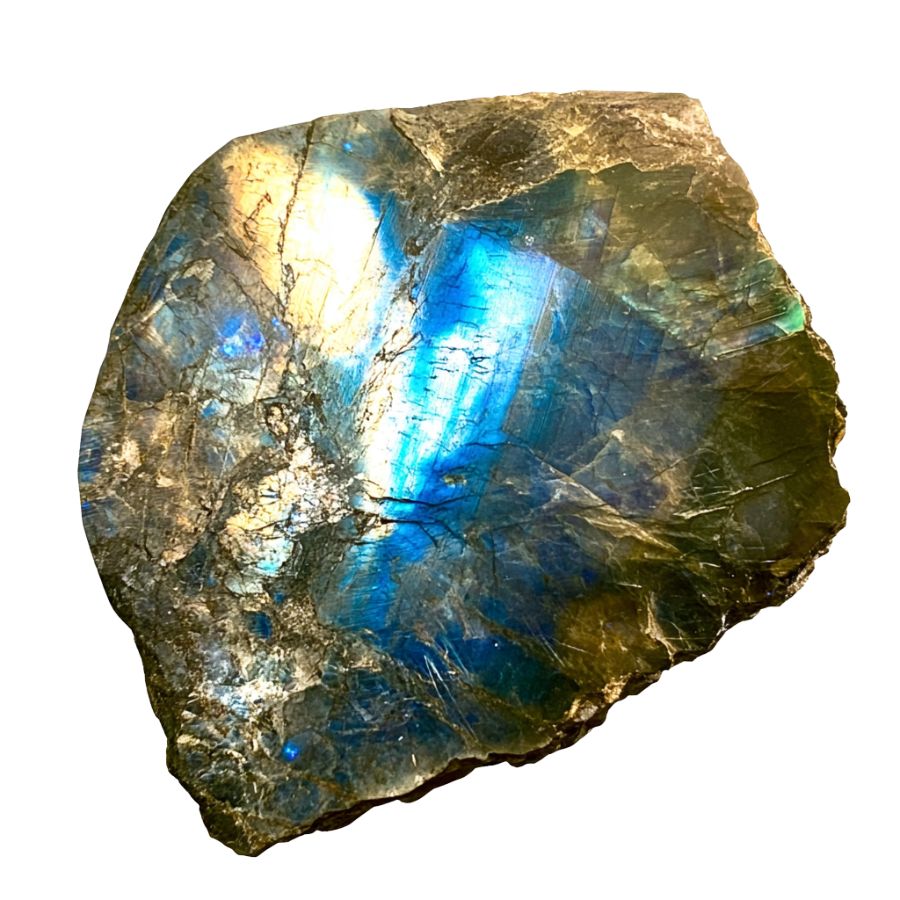

Blue Labradorite

Blue Labradorite stands out for its remarkable blue iridescence against a dark gray or black background. When light hits the stone’s surface, it creates a stunning display of electric blue flashes, sometimes accompanied by hints of green or violet.

The blue flashes appear most vivid when viewing the stone from specific angles, creating an almost magical transformation as you rotate it. This effect is often compared to the ethereal beauty of the Northern Lights.

Exceptional specimens display an intense, electric blue flash that covers a large portion of the stone’s surface. Some pieces also show secondary colors like aqua or sea green, adding depth to their visual appeal. The contrast between the dark base and bright blue flashes makes each piece unique.

Golden Labradorite

Golden Labradorite displays a mesmerizing golden-yellow sheen that sets it apart from other varieties. The stone’s surface exhibits brilliant flashes of gold and amber, creating a warm, sun-like glow that seems to emanate from within. These golden rays often appear alongside subtle hints of green or champagne colors.

What makes Golden Labradorite special is its ability to display multiple golden hues simultaneously. Some specimens show a range of colors from pale yellow to deep amber, creating a multi-dimensional effect.

The golden flash can vary in intensity and coverage, with premium specimens showing broad, bright areas of gold schiller.

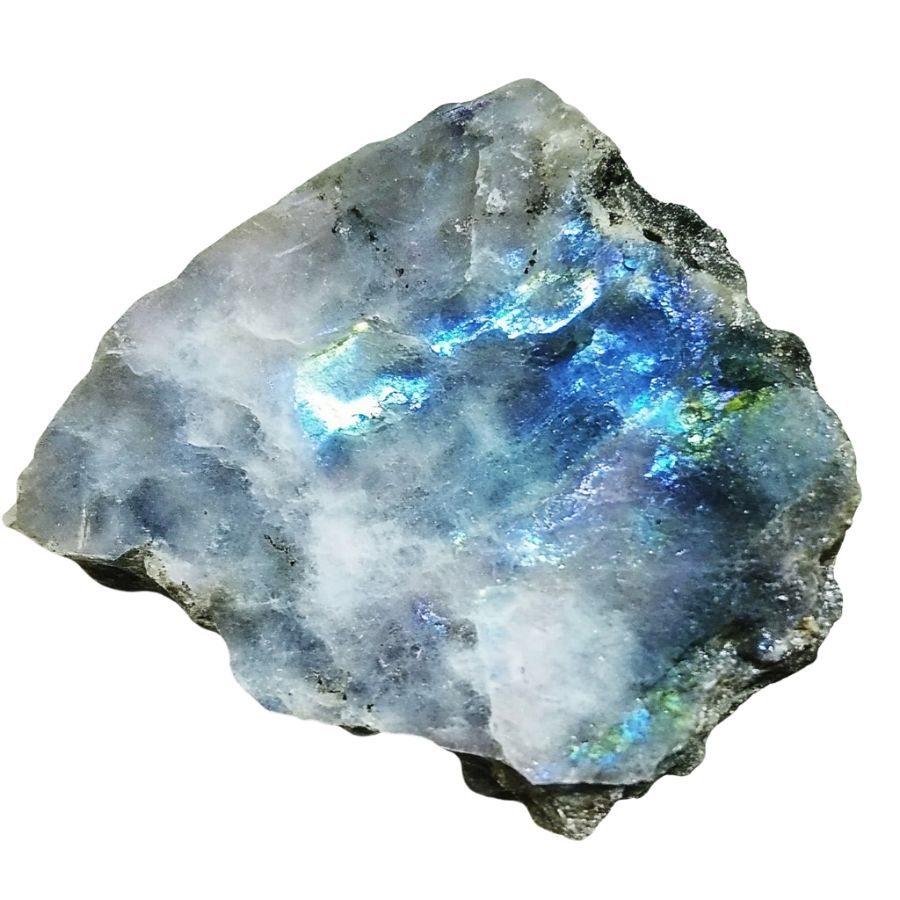

Rainbow Moonstone

Rainbow Moonstone Labradorite exhibits a distinctive white or colorless base with an enchanting blue sheen that floats across its surface. Blue sheen is often accompanied by flashes of other colors, including pink, yellow, and green.

This stone’s most captivating feature is how its colors appear to float just beneath the surface, creating an almost three-dimensional effect. As light moves across the stone, these colors shift and change, revealing new patterns and combinations. This creates a dynamic display that seems to change with every movement.

The stone’s transparency can range from translucent to semi-transparent, with the most valued pieces showing excellent clarity beneath their shimmering surface.

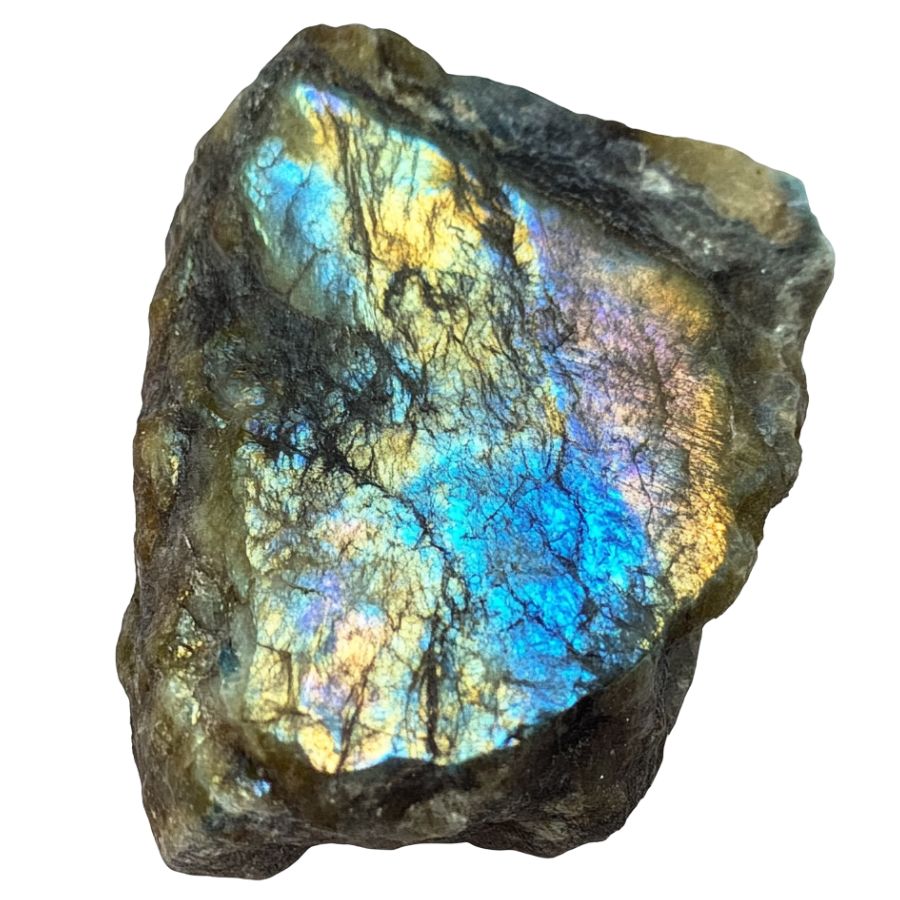

Spectrolite

Spectrolite reigns as the most dramatic member of this stone family, with its distinctive jet-black base setting it apart from other varieties.

What makes it truly special is that premium specimens can simultaneously display the complete spectrum of colors, from deep indigo to bright orange, emerald green to royal purple, all in a single piece.

The finest specimens possess what experts call “full-face color,” meaning the vibrant display covers most of the stone’s surface rather than appearing in small patches.

This characteristic, combined with its remarkable color intensity, has earned Spectrolite its reputation as the most visually impressive variety of all similar stones.

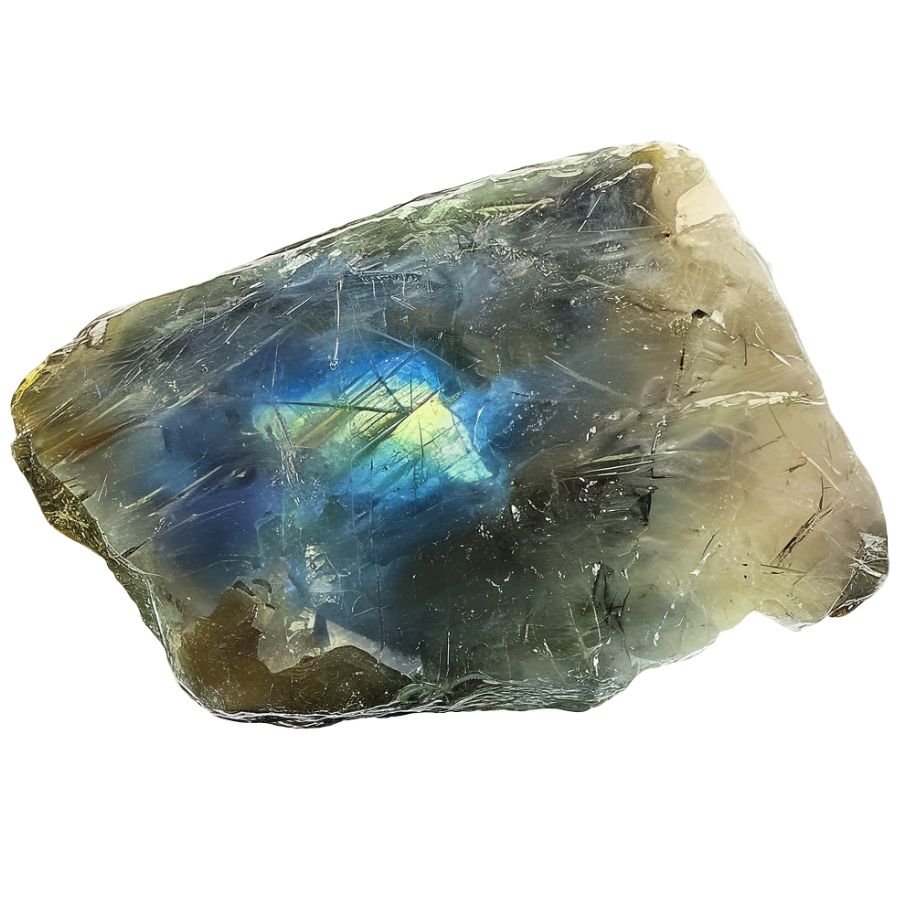

Transparent Labradorite

Transparent Labradorite exhibits a remarkable clarity that separates it from its opaque cousins. Crystal-clear areas allow light to pass through, creating an exceptional display of blue flashes against the transparent background.

Natural specimens often show areas of both transparency and translucency. Beautiful color changes occur as you move this stone, with the transparent areas revealing subtle blue sheens that seem to float within the crystal.

Some pieces display additional colors like soft greens or pale yellows, though the blue flash remains dominant.

Remarkable clarity combines with the signature color play to create stones that appear almost liquid-like.

Andesine-Labradorite

Reddish-orange hues dominate Andesine-Labradorite’s appearance, creating a warm and inviting glow. Delicate green and yellow streaks often appear throughout the stone, adding complexity to its color palette.

Metallic sparkles dance across the surface, different from the typical labradorescent effect. Fresh discoveries of this relatively new gemstone continue to reveal new color combinations.

Striking color variations appear in high-quality pieces, ranging from deep red to bright orange. Many specimens show subtle color zoning, where different hues blend together in distinct patterns.

Black Labradorite

Black Labradorite presents a dramatic dark canvas that emphasizes its colorful display. Bright flashes of color stand out dramatically against the deep black background, creating stunning visual contrast.

Most specimens show multiple colors at once, creating an eye-catching display. These color displays often include electric blues, emerald greens, and golden yellows, all visible simultaneously.

Natural sunlight brings out the boldest displays, while artificial light can highlight subtle color variations. Some specimens also show interesting patterns in how the colors are distributed.

Brown Labradorite

Brown Labradorite features rich earth tones ranging from deep chocolate to warm amber. Peach and orange undertones often appear throughout the stone, creating depth and dimension.

Multiple color zones create interesting patterns within each stone. These patterns can include stripes, swirls, or mottled areas that combine different brown and orange hues.

Subtle iridescence sometimes appears on the surface, adding an unexpected shimmer to the earthy colors. This effect is more subdued than in other varieties but adds an interesting dimension to the stone’s appearance.

If you want REAL results finding incredible rocks and minerals you need one of these 👇👇👇

Finding the coolest rocks in isn’t luck, it's knowing what to look for. Thousands of your fellow rock hunters are already carrying Rock Chasing field guides. Maybe it's time you joined the community.

Lightweight, mud-proof, and packed with clear photos, it’s become the go-to tool for anyone interested discovering what’s hidden under our red dirt and what they've already found.

Join them, and make your next rockhounding trip actually pay off.

What makes it different:

- 📍 Find and identify 140 incredible crystals, rocks, gemstones, minerals, and geodes across the USA

- 🚙 Field-tested across America's rivers, ranchlands, mountains, and roadcuts

- 📘 Heavy duty laminated pages resist dust, sweat, and water

- 🧠 Zero fluff — just clear visuals and straight-to-the-point info

- ⭐ Rated 4.8★ by real collectors who actually use it in the field

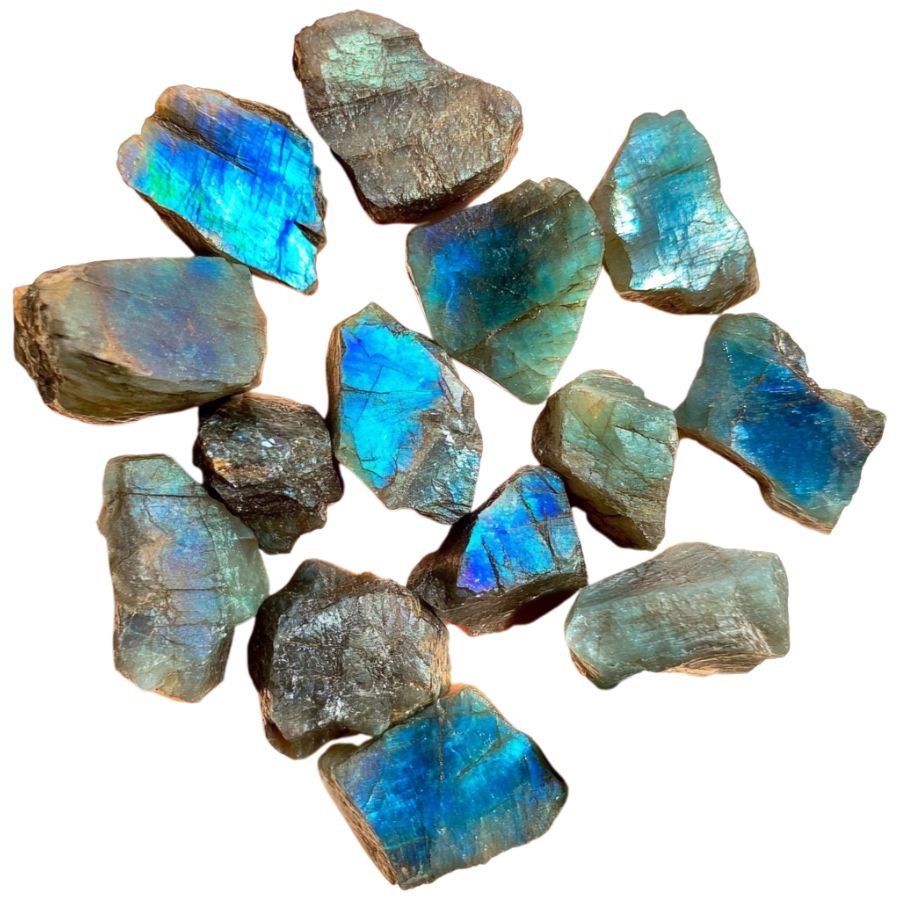

What Rough Labradorite Looks Like

Labradorite in its rough form can be tricky to spot, but once you know what to look for, it becomes easier. Here’s how to recognize this fascinating stone in its natural state.

Look for the Signature Flash

Raw labradorite often shows patches of its famous iridescent flash, even when unpolished. Check dark gray or black areas under direct sunlight – you might catch glimpses of blue, green, or gold shimmer.

Sometimes, you’ll need to wet the surface slightly to see this effect better. The flash isn’t always obvious but usually appears as scattered patches.

Check the Base Color and Texture

The main body should be dark gray to black, sometimes with a slight greenish tinge. The surface feels smooth but not glossy, similar to unpolished glass.

Look for a slightly bumpy texture with occasional flat surfaces. Fresh breaks will show a more uniform color than weathered surfaces.

Assess the Hardness and Breakage

Try scratching the surface with a copper penny – it shouldn’t leave a mark. The stone often breaks with smooth, flat surfaces at distinct angles.

You’ll notice these angular breaks are pretty characteristic, unlike random rough breaks in common rocks.

Test the Translucency

Hold a thin edge up to strong light. Raw labradorite should show some translucency, appearing slightly cloudy rather than completely opaque. The edges might look slightly whitish or gray when light passes through. Thicker pieces will appear darker and more opaque.

A Quick Request About Collecting

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Tips on Where to Look

Labradorite isn’t super common in everyday places, but with some smart searching, you can find it. Here’s where you should look:

Metamorphic Rock Formations

Look for dark-colored rock outcrops. Spot areas with lots of feldspar minerals. Check exposed cliff faces. Sometimes, when the sun hits just right, you might catch that signature blue flash from larger formations that’s a dead giveaway for labradorite presence.

Glacial Deposits

Search river beds after glacial deposits. Check gravel pits near old glacial paths. Look for smooth, dark gray stones mixed with other rocks. These deposits often contain chunks of labradorite that have broken off from larger formations and been carried downstream over thousands of years.

Mining Tailings

Visit abandoned feldspar mines. Check mine dump areas. Dig through tailings piles. Look for flat, shiny surfaces. The waste rock from old mining operations often contains overlooked pieces of labradorite that weren’t considered valuable during active mining periods but are perfect for collectors.

Stream Beds

Search clear-water streams. Look under water-worn rocks. Check gravel bars after rain. Spot dark, plate-like stones. The constant water movement often exposes and polishes these stones, making them easier to identify when wet.

Some Great Places To Start

Here are some of the better places in the state to start looking for Labradorite:

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Lemington

Lemington is a small town in Essex County. The town is home to Monadnock Mountain, which rises to 3,148 feet and gives amazing views of the area. This mountain is special because it’s part of the northernmost alkali-syenite rocks in New England.

Many rockhounds visit Lemington for its rich mineral deposits. Labradorite can be found in several spots around Monadnock Mountain, especially on its eastern slopes. Try hiking the Monadnock Mountain Trail, which leads to areas where collectors have had success.

The area near the old Norton Mine at the mountain’s base is another good spot to check. Spring is often the best time to visit, as melting snow can reveal new specimens in the soil and rock outcrops.

Cuttingsville

Cuttingsville is a small village in Shrewsbury, about 9.5 miles from Rutland city. The village sits along the Mill River and has interesting geology that attracts mineral enthusiasts. The area is famous for the Cuttingsville Complex, a group of special igneous rocks from the Early Cretaceous period.

These rocks include different types, like syenite and gabbro-diorite, that contain various minerals. Copperas Hill, located on the southwest part of the valley, is a key spot for rockhounds. This hill was once mined for iron sulfate production.

The diverse rock types in this area make it excellent for finding labradorite. The best places to look are around the old open-pit mine workings above the gravel road east of where the Cuttingsville railroad station used to be.

Granite Hill is another good spot where collectors have found interesting mineral specimens alongside labradorite.

Killington

Killington is best known for its popular ski resort in Rutland County. The area features beautiful Green Mountain scenery and trails that wind through varied rock formations. The town’s bedrock consists mainly of metamorphic and igneous rocks that formed millions of years ago.

Calvin Coolidge State Forest on the west side of Killington offers good rockhounding opportunities. The forest has numerous trails, including the Bucklin Trail, where exposed rock outcrops can yield labradorite specimens.

The areas around Killington Peak also show promise for mineral collectors. Here, the changing elevations expose different rock layers where labradorite might be found.

Road cuts throughout the town provide easy access to freshly exposed rock faces. After heavy rains is a great time to search these cuts as water washes away dirt to reveal new specimens.

Burke

Burke is located in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom region. The town features the impressive Burke Mountain and beautiful landscapes shaped by ancient glaciers. The area’s rocks tell a fascinating story of Earth’s powerful forces.

Most of Burke’s bedrock consists of metamorphic rocks like schists, gneisses, and quartzites. These rocks are mixed with igneous intrusions that bring mineral variety to the region. Ice Age remnants like kame terraces and eskers dot the landscape and sometimes contain mineral deposits.

Eastern and southeastern slopes of Burke Mountain offer good labradorite hunting spots, especially near where Dish Mill Brook meets the East Branch of the Passumpsic River. Here, exposed metamorphic rocks often contain feldspar minerals.

The terraces near East Burke village, created by glacial activity, contain sand and gravel deposits that sometimes yield labradorite fragments. Another promising location is around Weir Mill Brook, which drains the southern part of Burke Mountain. This area exposes bedrock and mineral veins worth exploring.

Dollif Mountain

Dollif Mountain stands at 1,878 feet in northeastern Vermont near Island Pond. This mountain may not be very tall, but it holds geological treasures that make it worth visiting.

The mountain consists mostly of granite and quartz monzonite from the Waits River Formation, which dates back about 400 million years. These rocks formed during the Late Silurian to Early Devonian periods and went through major changes during mountain-building events.

The southwestern slopes of Dollif Mountain offer the best spots for finding labradorite. In these areas, natural erosion and old logging activities have exposed more of the bedrock.

Look especially where the igneous rocks meet metamorphic rocks, as these contact zones often contain feldspar-rich areas where labradorite forms. Small stream beds and natural clearings on the mountain provide excellent hunting grounds.

Places Labradorite has been found by County

After discussing our top picks, we wanted to discuss the other places on our list. Below is a list of the additional locations along with a breakdown of each place by county.

| County | Location |

| Addison | Weybridge |

| Grand Isle | South Hero |

| Caledonia | Kirby |

| Windsor | Mount Ascutney |

| Chittenden | Underhill |

| Franklin | Dead River Headwaters |

| Orleans | Eden |

| Washington | Barre |

| Caledonia | Lyndonville |

| Franklin | Richford |

| Orleans | Derby |

| Windham | Bellows Falls |

| Windsor | Proctorsville |

| Orleans | North Troy |

| Orleans | Mount Pisgah |