Hunting for labradorite in North Carolina can leave you feeling lost and frustrated. Many rockhounds spend hours searching without finding anything worth keeping.

I’ve also been there, driving to spots mentioned online only to find they’ve been picked clean. It’s disappointing to come home empty-handed after a day of digging and searching.

You can find real, working spots where you can still find labradorite today. I’ll share the exact locations that local collectors don’t advertise, plus tips on how to spot the stone’s blue-green flash even when it’s covered in dirt.

How Labradorite Forms Here

Labradorite forms deep underground when magma slowly cools and crystallizes. The process happens when different minerals separate while cooling, creating thin layers stacked on top of each other. These layers have slightly different chemical makeups, usually about 1 micron thick.

When light hits these layers, it creates that stunning blue-green flash we love, called labradorescence. The stone starts out as a mix of calcium, sodium, aluminum, and silicate minerals.

As it cools, these minerals organize themselves into this layered pattern, which happens most often in places where magma intrudes into the surrounding rock. It’s like nature’s own light show, frozen in stone.

Types of Labradorite

Labradorite comes in several distinct varieties. Each type exhibits special qualities that make it sought after by collectors.

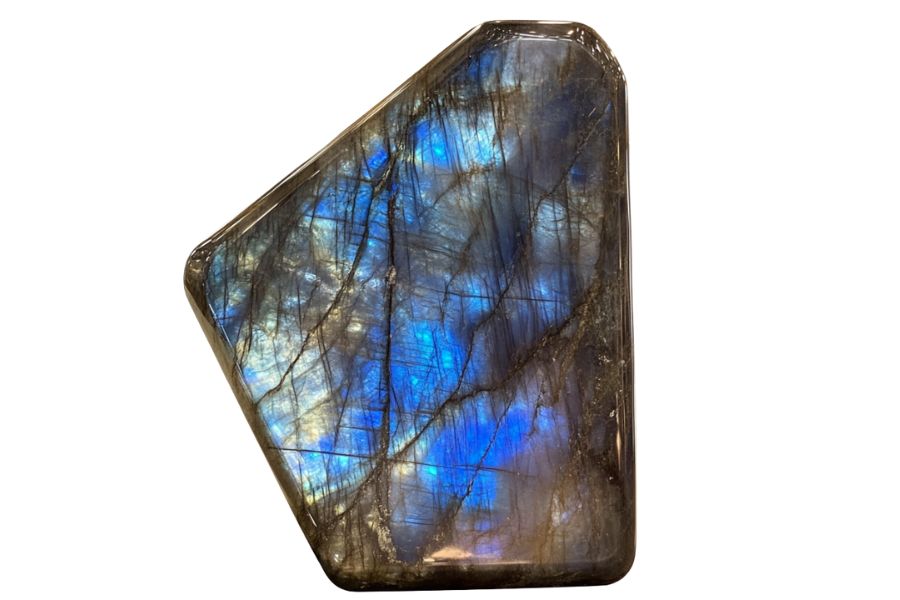

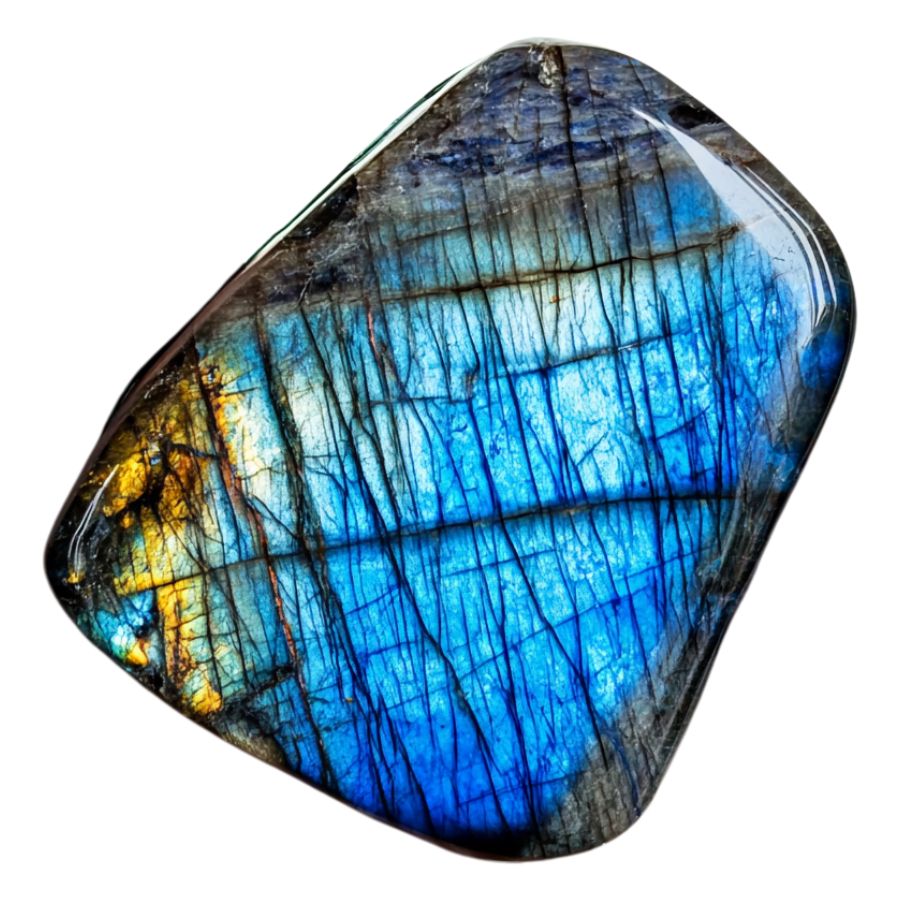

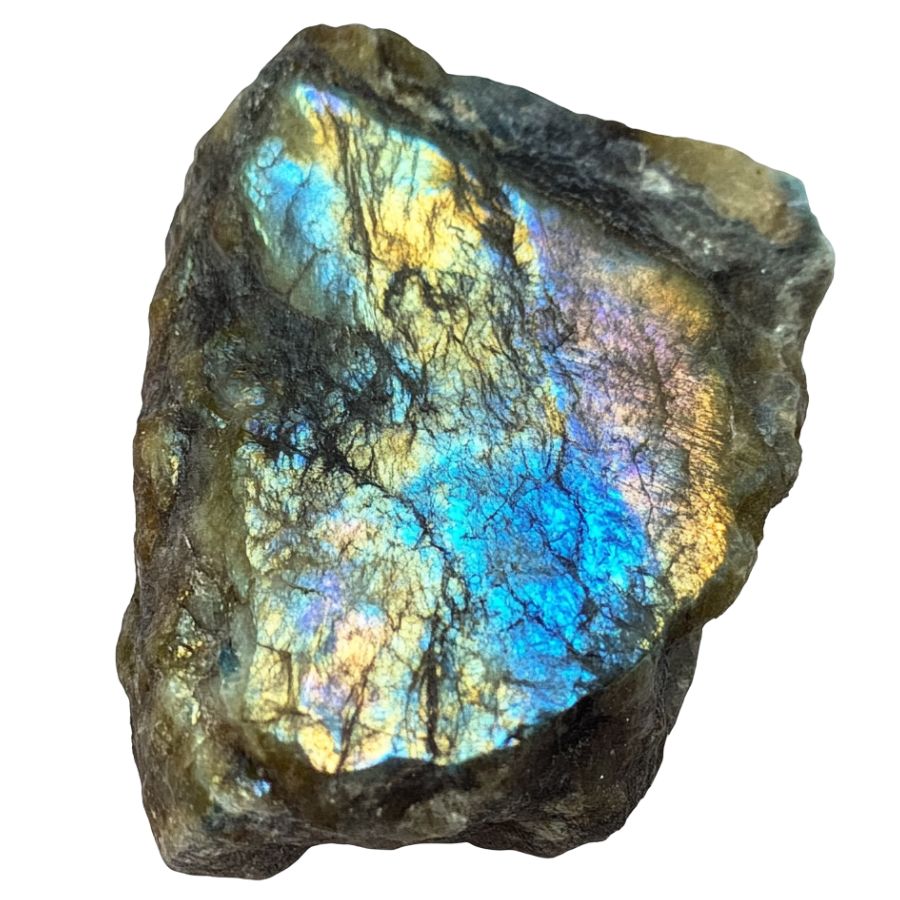

Blue Labradorite

Blue Labradorite stands out for its remarkable blue iridescence against a dark gray or black background. When light hits the stone’s surface, it creates a stunning display of electric blue flashes, sometimes accompanied by hints of green or violet.

The blue flashes appear most vivid when viewing the stone from specific angles, creating an almost magical transformation as you rotate it. This effect is often compared to the ethereal beauty of the Northern Lights.

Exceptional specimens display an intense, electric blue flash that covers a large portion of the stone’s surface. Some pieces also show secondary colors like aqua or sea green, adding depth to their visual appeal. The contrast between the dark base and bright blue flashes makes each piece unique.

Golden Labradorite

Golden Labradorite displays a mesmerizing golden-yellow sheen that sets it apart from other varieties. The stone’s surface exhibits brilliant flashes of gold and amber, creating a warm, sun-like glow that seems to emanate from within. These golden rays often appear alongside subtle hints of green or champagne colors.

What makes Golden Labradorite special is its ability to display multiple golden hues simultaneously. Some specimens show a range of colors from pale yellow to deep amber, creating a multi-dimensional effect.

The golden flash can vary in intensity and coverage, with premium specimens showing broad, bright areas of gold schiller.

Rainbow Moonstone

Rainbow Moonstone Labradorite exhibits a distinctive white or colorless base with an enchanting blue sheen that floats across its surface. Blue sheen is often accompanied by flashes of other colors, including pink, yellow, and green.

This stone’s most captivating feature is how its colors appear to float just beneath the surface, creating an almost three-dimensional effect. As light moves across the stone, these colors shift and change, revealing new patterns and combinations. This creates a dynamic display that seems to change with every movement.

The stone’s transparency can range from translucent to semi-transparent, with the most valued pieces showing excellent clarity beneath their shimmering surface.

Spectrolite

Spectrolite reigns as the most dramatic member of this stone family, with its distinctive jet-black base setting it apart from other varieties.

What makes it truly special is that premium specimens can simultaneously display the complete spectrum of colors, from deep indigo to bright orange, emerald green to royal purple, all in a single piece.

The finest specimens possess what experts call “full-face color,” meaning the vibrant display covers most of the stone’s surface rather than appearing in small patches.

This characteristic, combined with its remarkable color intensity, has earned Spectrolite its reputation as the most visually impressive variety of all similar stones.

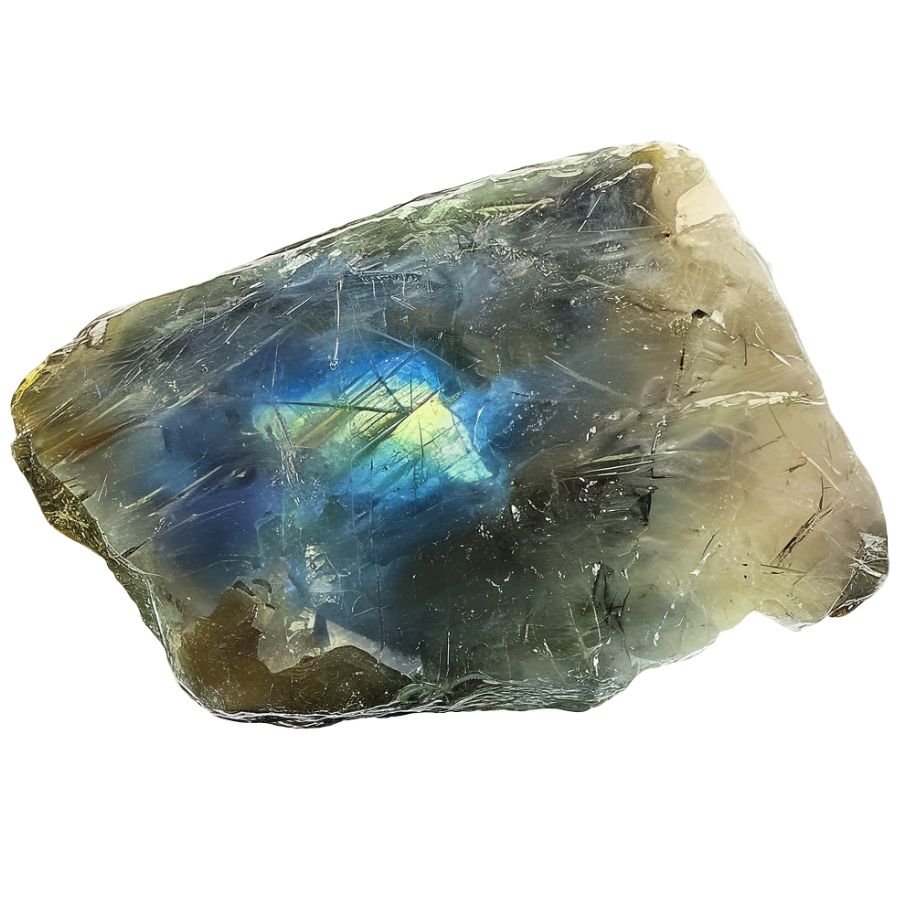

Transparent Labradorite

Transparent Labradorite exhibits a remarkable clarity that separates it from its opaque cousins. Crystal-clear areas allow light to pass through, creating an exceptional display of blue flashes against the transparent background.

Natural specimens often show areas of both transparency and translucency. Beautiful color changes occur as you move this stone, with the transparent areas revealing subtle blue sheens that seem to float within the crystal.

Some pieces display additional colors like soft greens or pale yellows, though the blue flash remains dominant.

Remarkable clarity combines with the signature color play to create stones that appear almost liquid-like.

Andesine-Labradorite

Reddish-orange hues dominate Andesine-Labradorite’s appearance, creating a warm and inviting glow. Delicate green and yellow streaks often appear throughout the stone, adding complexity to its color palette.

Metallic sparkles dance across the surface, different from the typical labradorescent effect. Fresh discoveries of this relatively new gemstone continue to reveal new color combinations.

Striking color variations appear in high-quality pieces, ranging from deep red to bright orange. Many specimens show subtle color zoning, where different hues blend together in distinct patterns.

Black Labradorite

Black Labradorite presents a dramatic dark canvas that emphasizes its colorful display. Bright flashes of color stand out dramatically against the deep black background, creating stunning visual contrast.

Most specimens show multiple colors at once, creating an eye-catching display. These color displays often include electric blues, emerald greens, and golden yellows, all visible simultaneously.

Natural sunlight brings out the boldest displays, while artificial light can highlight subtle color variations. Some specimens also show interesting patterns in how the colors are distributed.

Brown Labradorite

Brown Labradorite features rich earth tones ranging from deep chocolate to warm amber. Peach and orange undertones often appear throughout the stone, creating depth and dimension.

Multiple color zones create interesting patterns within each stone. These patterns can include stripes, swirls, or mottled areas that combine different brown and orange hues.

Subtle iridescence sometimes appears on the surface, adding an unexpected shimmer to the earthy colors. This effect is more subdued than in other varieties but adds an interesting dimension to the stone’s appearance.

If you want REAL results finding incredible rocks and minerals you need one of these 👇👇👇

Finding the coolest rocks in isn’t luck, it's knowing what to look for. Thousands of your fellow rock hunters are already carrying Rock Chasing field guides. Maybe it's time you joined the community.

Lightweight, mud-proof, and packed with clear photos, it’s become the go-to tool for anyone interested discovering what’s hidden under our red dirt and what they've already found.

Join them, and make your next rockhounding trip actually pay off.

What makes it different:

- 📍 Find and identify 140 incredible crystals, rocks, gemstones, minerals, and geodes across the USA

- 🚙 Field-tested across America's rivers, ranchlands, mountains, and roadcuts

- 📘 Heavy duty laminated pages resist dust, sweat, and water

- 🧠 Zero fluff — just clear visuals and straight-to-the-point info

- ⭐ Rated 4.8★ by real collectors who actually use it in the field

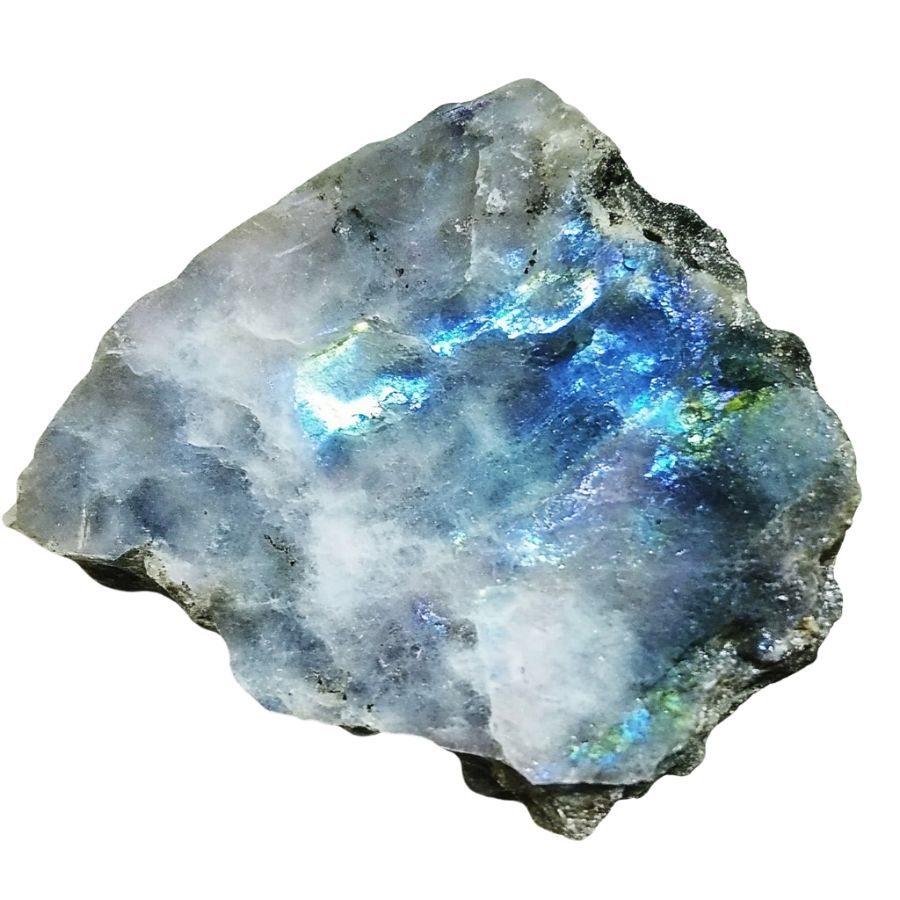

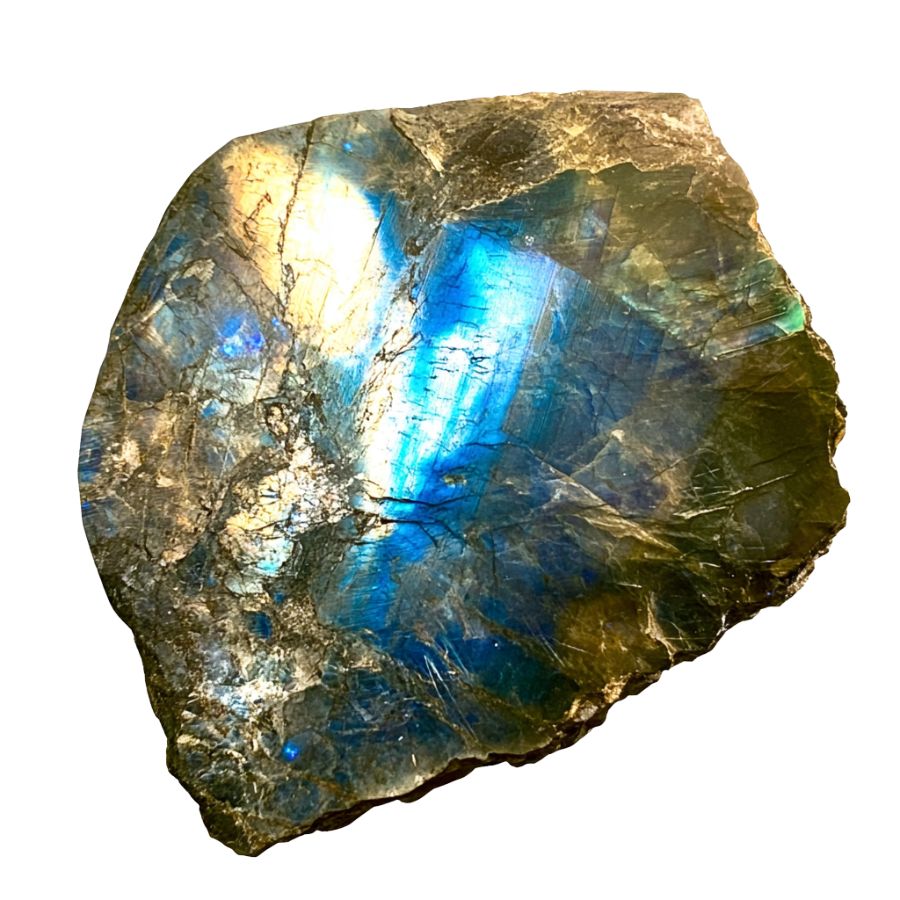

What Rough Labradorite Looks Like

Labradorite in its rough form can be tricky to spot, but once you know what to look for, it becomes easier. Here’s how to recognize this fascinating stone in its natural state.

Look for the Signature Flash

Raw labradorite often shows patches of its famous iridescent flash, even when unpolished. Check dark gray or black areas under direct sunlight – you might catch glimpses of blue, green, or gold shimmer.

Sometimes, you’ll need to wet the surface slightly to see this effect better. The flash isn’t always obvious but usually appears as scattered patches.

Check the Base Color and Texture

The main body should be dark gray to black, sometimes with a slight greenish tinge. The surface feels smooth but not glossy, similar to unpolished glass.

Look for a slightly bumpy texture with occasional flat surfaces. Fresh breaks will show a more uniform color than weathered surfaces.

Assess the Hardness and Breakage

Try scratching the surface with a copper penny – it shouldn’t leave a mark. The stone often breaks with smooth, flat surfaces at distinct angles.

You’ll notice these angular breaks are pretty characteristic, unlike random rough breaks in common rocks.

Test the Translucency

Hold a thin edge up to strong light. Raw labradorite should show some translucency, appearing slightly cloudy rather than completely opaque. The edges might look slightly whitish or gray when light passes through. Thicker pieces will appear darker and more opaque.

A Quick Request About Collecting

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Tips on Where to Look

Labradorite isn’t super common in everyday places, but with some smart searching, you can find it. Here’s where you should look:

Metamorphic Rock Formations

Look for dark-colored rock outcrops. Spot areas with lots of feldspar minerals. Check exposed cliff faces. Sometimes, when the sun hits just right, you might catch that signature blue flash from larger formations that’s a dead giveaway for labradorite presence.

Glacial Deposits

Search river beds after glacial deposits. Check gravel pits near old glacial paths. Look for smooth, dark gray stones mixed with other rocks. These deposits often contain chunks of labradorite that have broken off from larger formations and been carried downstream over thousands of years.

Mining Tailings

Visit abandoned feldspar mines. Check mine dump areas. Dig through tailings piles. Look for flat, shiny surfaces. The waste rock from old mining operations often contains overlooked pieces of labradorite that weren’t considered valuable during active mining periods but are perfect for collectors.

Stream Beds

Search clear-water streams. Look under water-worn rocks. Check gravel bars after rain. Spot dark, plate-like stones. The constant water movement often exposes and polishes these stones, making them easier to identify when wet.

Some Great Places To Start

Here are some of the better places in the state to start looking for Labradorite:

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Kings Mountain

Kings Mountain is located in Cleveland County, about 30 miles west of Charlotte. The area sits on the border with South Carolina and forms part of the Kings Mountain Range, known for its quartzite ridges.

This region has a rich mineral history with labradorite and other valuable minerals like spodumene, mica, and feldspar found here.

Kings Mountain marks the boundary between the Inner Piedmont and Carolina terranes, creating a unique mix of metamorphic and igneous rocks. These geological conditions have produced numerous pegmatites.

Rockhounds can find labradorite in the exposed pegmatite areas, particularly around old mine dumps and natural outcrops along ridges. The High Shoals Granite area is especially good for finding this beautiful stone with its famous blue flash.

Kings Mountain’s mining heritage makes it a favorite spot for mineral collectors who come equipped with basic tools to carefully extract specimens from the surrounding rock.

South Toe River

The South Toe River flows through Yancey County in North Carolina’s Appalachian region. This water body starts high up near the Eastern Continental Divide, between the Black Mountains and Blue Ridge Parkway, then travels north alongside Highway 80. Eventually, it joins the North Toe River.

Labradorite has been discovered in this rocky river area. The river’s location near the Black Mountains is significant; these mountains are among the oldest in the world. Many rock collectors visit this spot because of its rich mineral variety.

Check the riverbanks and streambeds where water has uncovered hidden stones. Areas with gravel bars or where the river cuts through bedrock often yield the best results. Bright sunlight helps spot labradorite’s special blue-green flash when wet.

The South Toe River area offers more than just labradorite. Visitors can sometimes find garnets, mica, and quartz while searching for the more elusive labradorite specimens.

Franklin Area

Franklin is located in Macon County. This small town is surrounded by the beautiful Appalachian Mountains, making it a perfect spot for gem hunters. Franklin has earned the nickname “Gem Capital of the World” because of its rich mineral deposits.

Labradorite can be found in this area, especially around the Bryson Branch Mine. The town has a unique geological history dating back millions of years, when intense heat and pressure created perfect conditions for gemstone formation.

Many rockhounds visit the local mines, where they can search through mine tailings (leftover rock piles) for labradorite specimens.

Several commercial gem mines in Franklin allow visitors to dig for treasures. Mason’s Ruby and Sapphire Mine and Sheffield Mine are popular spots where you might discover labradorite alongside other gems like garnets, rubies, and sapphires.

Uwharrie River

The Uwharrie River flows through Montgomery County. It runs southward through the ancient Uwharrie Mountains and the Uwharrie National Forest in the central part of the state. This river is a tributary of the larger Pee Dee River system.

Your best chances of finding labradorite are along eroded riverbanks where water has exposed underlying rock layers. Specimens have been discovered along this riverbed, making it a target spot for gem hunters.

After heavy rains, new material gets washed downstream, creating fresh hunting opportunities.

Many rockhounds also search near old mining sites within the Uwharrie National Forest, where mineral deposits are concentrated. The forest’s numerous streams and tributaries provide additional locations worth exploring.

Mitchell Area

Mitchell Area is located in western North Carolina, part of the beautiful Blue Ridge Mountains. The area includes the famous Spruce Pine Mining District, which stretches about 25 miles long and 10 miles wide.

Rockhounds can find labradorite in Mitchell County alongside other popular minerals like feldspar, mica, quartz, and garnet. The area is well-known for its pegmatites.

Many local mines and quarries in the Spruce Pine district offer opportunities for gem hunters. These spots contain numerous pegmatite formations where labradorite might be hiding.

Some public collecting sites allow visitors to search through mine tailings, where rejected rock material often contains overlooked treasures.

Places Labradorite has been found by County

After discussing our top picks, we wanted to discuss the other places on our list. Below is a list of the additional locations along with a breakdown of each place by county.

| County | Location |

| Buncombe | Thomas Mine |

| Cabarrus | Concord |

| Clay | Buck Creek Mine |

| Davie | Farmington Gabbro-Metagabbro Pluton |

| Granville | Hornblende Deposit |

| Mecklenburg | Charlotte |

| Mecklenburg | Capps Hill Mine |

| Mecklenburg | Mecklenburg Gabbro-Metagabbro Complex |

| Macon | Cullasaja River |

| Macon | Wayah Bald |

| Macon | Standing Indian Mountain |

| Macon | Bartram Trail |

| Wake | Neuse River |

| Gaston | Crowders Mountain |

| Haywood | Shining Rock Ledge |

| Yancey | Walker Creek |

| Ashe | Chalk Mountain |

| Clay | Lake Chatuge |

| Surry | Mount Airy |

| Rutherford | Chimney Rock |

| Transylvania | Pisgah Forest |

| Buncombe | Randall Glen |

| Swain | Smoky Mountain |

| Cleveland | Broad River |

| Mitchell | Bon Ami Mine |

| Stanly | Mountain Creek |

| Alexander | Hiddenite |