Labradorite can be found in New Jersey, and it’s worth keeping an eye out for if you’re into rocks with a bit of character. It’s a type of feldspar that flashes with color when the light hits it just right—usually blue, green, or gold.

Most of the good finds come from old quarries, road cuts, and rock piles left behind by construction. These spots give you access to gneiss and anorthosite, the types of rock where labradorite forms.

Some pieces don’t look like much on the surface, but break them open or rinse them off, and the color shows up. If you’re looking for places where people have actually found labradorite in New Jersey, these are the ones worth knowing.

How Labradorite Forms Here

Labradorite forms deep underground when magma slowly cools and crystallizes. The process happens when different minerals separate while cooling, creating thin layers stacked on top of each other. These layers have slightly different chemical makeups, usually about 1 micron thick.

When light hits these layers, it creates that stunning blue-green flash we love, called labradorescence. The stone starts out as a mix of calcium, sodium, aluminum, and silicate minerals.

As it cools, these minerals organize themselves into this layered pattern, which happens most often in places where magma intrudes into the surrounding rock. It’s like nature’s own light show, frozen in stone.

Types of Labradorite

Labradorite comes in several distinct varieties. Each type exhibits special qualities that make it sought after by collectors.

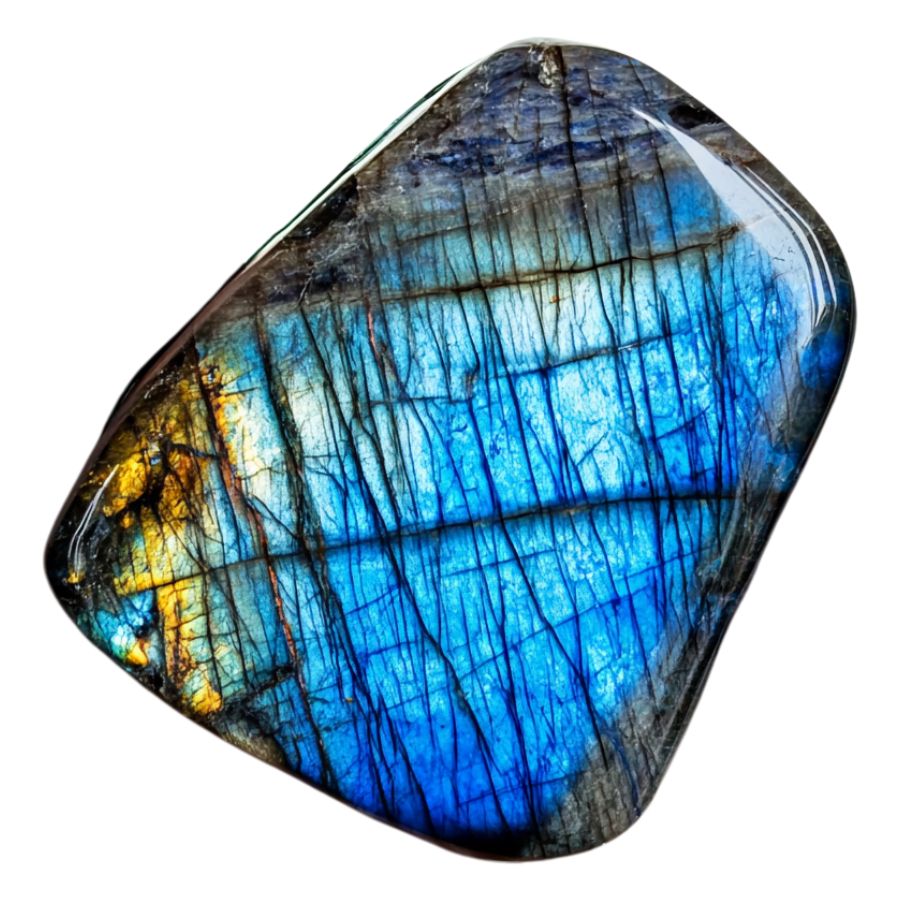

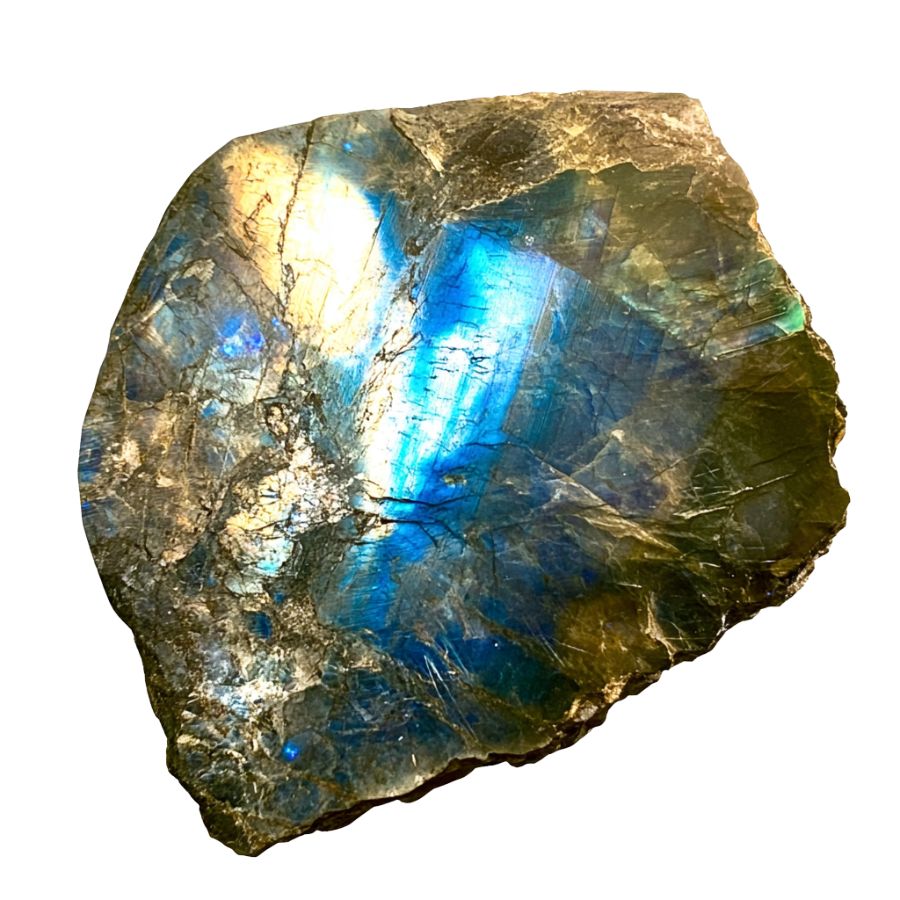

Blue Labradorite

Blue Labradorite stands out for its remarkable blue iridescence against a dark gray or black background. When light hits the stone’s surface, it creates a stunning display of electric blue flashes, sometimes accompanied by hints of green or violet.

The blue flashes appear most vivid when viewing the stone from specific angles, creating an almost magical transformation as you rotate it. This effect is often compared to the ethereal beauty of the Northern Lights.

Exceptional specimens display an intense, electric blue flash that covers a large portion of the stone’s surface. Some pieces also show secondary colors like aqua or sea green, adding depth to their visual appeal. The contrast between the dark base and bright blue flashes makes each piece unique.

Golden Labradorite

Golden Labradorite displays a mesmerizing golden-yellow sheen that sets it apart from other varieties. The stone’s surface exhibits brilliant flashes of gold and amber, creating a warm, sun-like glow that seems to emanate from within. These golden rays often appear alongside subtle hints of green or champagne colors.

What makes Golden Labradorite special is its ability to display multiple golden hues simultaneously. Some specimens show a range of colors from pale yellow to deep amber, creating a multi-dimensional effect.

The golden flash can vary in intensity and coverage, with premium specimens showing broad, bright areas of gold schiller.

Rainbow Moonstone

Rainbow Moonstone Labradorite exhibits a distinctive white or colorless base with an enchanting blue sheen that floats across its surface. Blue sheen is often accompanied by flashes of other colors, including pink, yellow, and green.

This stone’s most captivating feature is how its colors appear to float just beneath the surface, creating an almost three-dimensional effect. As light moves across the stone, these colors shift and change, revealing new patterns and combinations. This creates a dynamic display that seems to change with every movement.

The stone’s transparency can range from translucent to semi-transparent, with the most valued pieces showing excellent clarity beneath their shimmering surface.

Spectrolite

Spectrolite reigns as the most dramatic member of this stone family, with its distinctive jet-black base setting it apart from other varieties.

What makes it truly special is that premium specimens can simultaneously display the complete spectrum of colors, from deep indigo to bright orange, emerald green to royal purple, all in a single piece.

The finest specimens possess what experts call “full-face color,” meaning the vibrant display covers most of the stone’s surface rather than appearing in small patches.

This characteristic, combined with its remarkable color intensity, has earned Spectrolite its reputation as the most visually impressive variety of all similar stones.

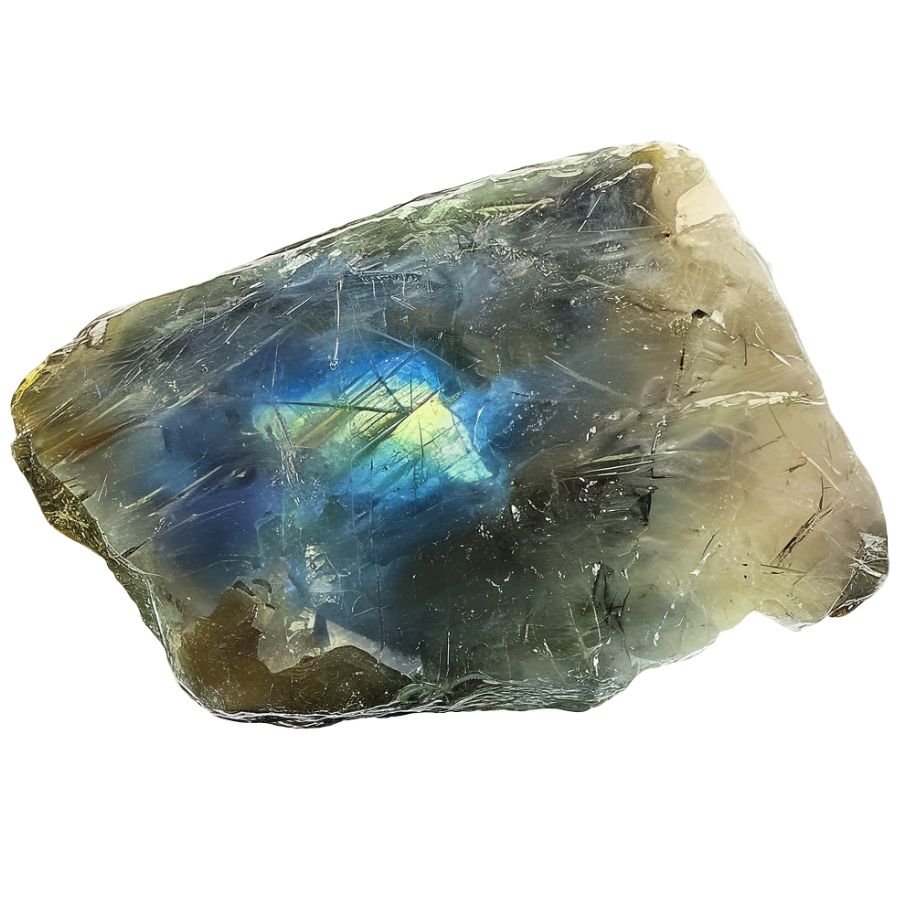

Transparent Labradorite

Transparent Labradorite exhibits a remarkable clarity that separates it from its opaque cousins. Crystal-clear areas allow light to pass through, creating an exceptional display of blue flashes against the transparent background.

Natural specimens often show areas of both transparency and translucency. Beautiful color changes occur as you move this stone, with the transparent areas revealing subtle blue sheens that seem to float within the crystal.

Some pieces display additional colors like soft greens or pale yellows, though the blue flash remains dominant.

Remarkable clarity combines with the signature color play to create stones that appear almost liquid-like.

Andesine-Labradorite

Reddish-orange hues dominate Andesine-Labradorite’s appearance, creating a warm and inviting glow. Delicate green and yellow streaks often appear throughout the stone, adding complexity to its color palette.

Metallic sparkles dance across the surface, different from the typical labradorescent effect. Fresh discoveries of this relatively new gemstone continue to reveal new color combinations.

Striking color variations appear in high-quality pieces, ranging from deep red to bright orange. Many specimens show subtle color zoning, where different hues blend together in distinct patterns.

Black Labradorite

Black Labradorite presents a dramatic dark canvas that emphasizes its colorful display. Bright flashes of color stand out dramatically against the deep black background, creating stunning visual contrast.

Most specimens show multiple colors at once, creating an eye-catching display. These color displays often include electric blues, emerald greens, and golden yellows, all visible simultaneously.

Natural sunlight brings out the boldest displays, while artificial light can highlight subtle color variations. Some specimens also show interesting patterns in how the colors are distributed.

Brown Labradorite

Brown Labradorite features rich earth tones ranging from deep chocolate to warm amber. Peach and orange undertones often appear throughout the stone, creating depth and dimension.

Multiple color zones create interesting patterns within each stone. These patterns can include stripes, swirls, or mottled areas that combine different brown and orange hues.

Subtle iridescence sometimes appears on the surface, adding an unexpected shimmer to the earthy colors. This effect is more subdued than in other varieties but adds an interesting dimension to the stone’s appearance.

If you want REAL results finding incredible rocks and minerals you need one of these 👇👇👇

Finding the coolest rocks in isn’t luck, it's knowing what to look for. Thousands of your fellow rock hunters are already carrying Rock Chasing field guides. Maybe it's time you joined the community.

Lightweight, mud-proof, and packed with clear photos, it’s become the go-to tool for anyone interested discovering what’s hidden under our red dirt and what they've already found.

Join them, and make your next rockhounding trip actually pay off.

What makes it different:

- 📍 Find and identify 140 incredible crystals, rocks, gemstones, minerals, and geodes across the USA

- 🚙 Field-tested across America's rivers, ranchlands, mountains, and roadcuts

- 📘 Heavy duty laminated pages resist dust, sweat, and water

- 🧠 Zero fluff — just clear visuals and straight-to-the-point info

- ⭐ Rated 4.8★ by real collectors who actually use it in the field

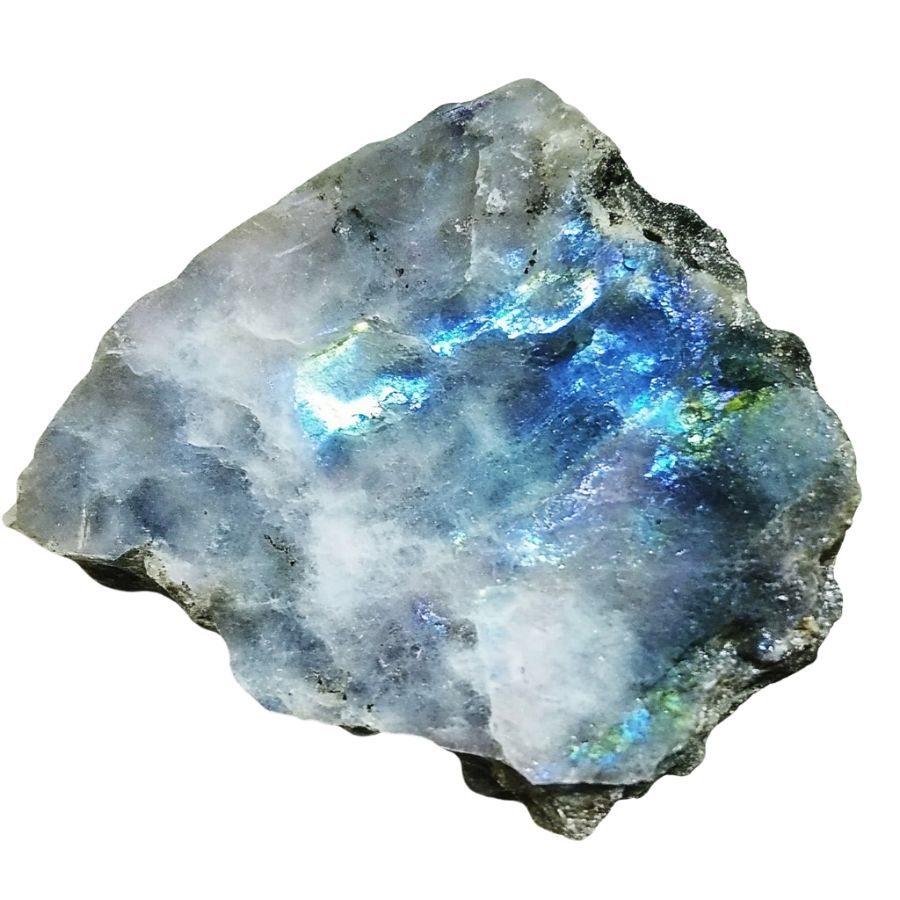

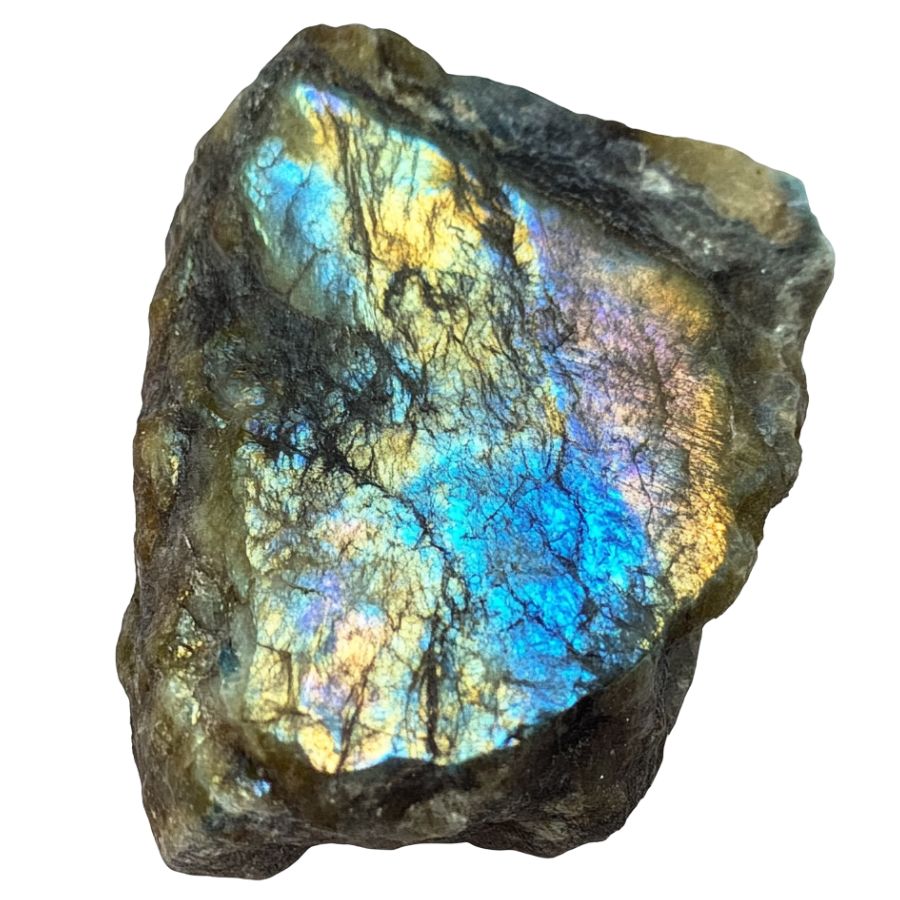

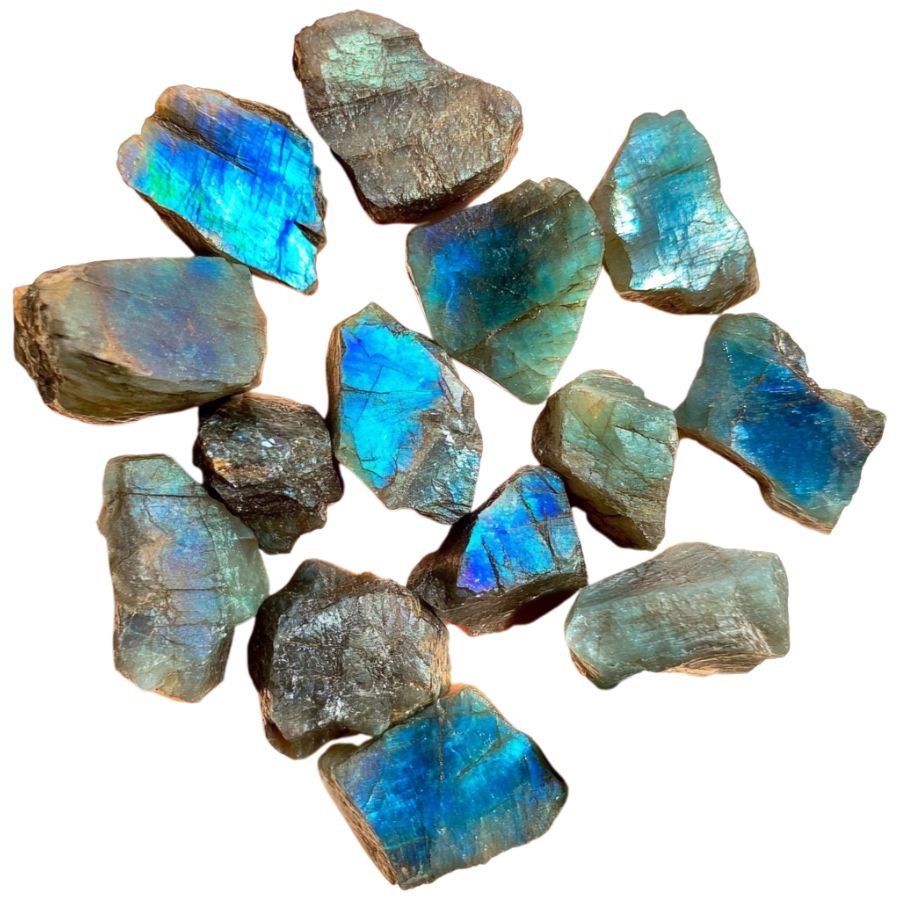

What Rough Labradorite Looks Like

Labradorite in its rough form can be tricky to spot, but once you know what to look for, it becomes easier. Here’s how to recognize this fascinating stone in its natural state.

Look for the Signature Flash

Raw labradorite often shows patches of its famous iridescent flash, even when unpolished. Check dark gray or black areas under direct sunlight – you might catch glimpses of blue, green, or gold shimmer.

Sometimes, you’ll need to wet the surface slightly to see this effect better. The flash isn’t always obvious but usually appears as scattered patches.

Check the Base Color and Texture

The main body should be dark gray to black, sometimes with a slight greenish tinge. The surface feels smooth but not glossy, similar to unpolished glass.

Look for a slightly bumpy texture with occasional flat surfaces. Fresh breaks will show a more uniform color than weathered surfaces.

Assess the Hardness and Breakage

Try scratching the surface with a copper penny – it shouldn’t leave a mark. The stone often breaks with smooth, flat surfaces at distinct angles.

You’ll notice these angular breaks are pretty characteristic, unlike random rough breaks in common rocks.

Test the Translucency

Hold a thin edge up to strong light. Raw labradorite should show some translucency, appearing slightly cloudy rather than completely opaque. The edges might look slightly whitish or gray when light passes through. Thicker pieces will appear darker and more opaque.

A Quick Request About Collecting

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Tips on Where to Look

Labradorite isn’t super common in everyday places, but with some smart searching, you can find it. Here’s where you should look:

Metamorphic Rock Formations

Look for dark-colored rock outcrops. Spot areas with lots of feldspar minerals. Check exposed cliff faces. Sometimes, when the sun hits just right, you might catch that signature blue flash from larger formations that’s a dead giveaway for labradorite presence.

Glacial Deposits

Search river beds after glacial deposits. Check gravel pits near old glacial paths. Look for smooth, dark gray stones mixed with other rocks. These deposits often contain chunks of labradorite that have broken off from larger formations and been carried downstream over thousands of years.

Mining Tailings

Visit abandoned feldspar mines. Check mine dump areas. Dig through tailings piles. Look for flat, shiny surfaces. The waste rock from old mining operations often contains overlooked pieces of labradorite that weren’t considered valuable during active mining periods but are perfect for collectors.

Stream Beds

Search clear-water streams. Look under water-worn rocks. Check gravel bars after rain. Spot dark, plate-like stones. The constant water movement often exposes and polishes these stones, making them easier to identify when wet.

Some Great Places To Start

Here are some of the better places in the state to start looking for Labradorite:

Always Confirm Access and Collection Rules!

Before heading out to any of the locations on our list you need to confirm access requirements and collection rules for both public and private locations directly with the location. We haven’t personally verified every location and the access requirements and collection rules often change without notice.

Many of the locations we mention will not allow collecting but are still great places for those who love to find beautiful rocks and minerals in the wild without keeping them. We also can’t guarantee you will find anything in these locations since they are constantly changing.

Always get updated information directly from the source ahead of time to ensure responsible rockhounding. If you want even more current options it’s always a good idea to contact local rock and mineral clubs and groups

Watchung Mountains

The Watchung Mountains in Essex County are a series of curved ridges in the northern part of the state. These mountains formed from lava flows during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods, creating basalt ridges that reach about 600 feet above sea level. They stretch from Somerset County toward the New York border.

Labradorite can be found in these mountains due to their volcanic history. The area contains lots of igneous rocks formed from ancient lava flows. These rocks often hold various minerals, including the colorful labradorite.

Look for labradorite in places where basalt layers are visible. Good spots include exposed rock faces, quarries, and natural outcrops throughout the mountains.

Hiking trails throughout the mountains offer both beautiful views and access to potential rockhounding sites.

Manasquan Beach

Manasquan Beach is located along the Jersey Shore in Monmouth County. This popular Atlantic Ocean beach is a spot where rockhounds search for interesting minerals.

The beach is part of the Manasquan Formation, which formed during the Eocene epoch about 50 million years ago. These ancient layers contain greensand deposits rich in minerals like glauconite and quartz.

Your best chance of finding labradorite is after storms when waves wash up fresh material. Look where darker sand meets the tideline, as these areas often contain heavier minerals.

Early morning searches help because the low angle of sunlight makes labradorite’s blue-green flash easier to spot.

Pennington Mountain

Pennington Mountain stands in Hopewell Township, Mercer County, with a height of 253 feet. This small peak is found in the central-western part of the state, close to the Delaware River. Local towns like Marshalls Corner and Glenmoore surround this notable landmark.

Labradorite can be discovered in this area among the mountain’s unique rock formations. The geological structure of Pennington Mountain makes it special for mineral hunters. Its summit features interesting landforms that have formed over millions of years.

Look for Labradorite in exposed rock faces and crevices throughout the mountain. Many collectors have success searching areas with visible mineral deposits where the colorful play of light (called labradorescence) can be spotted on freshly broken surfaces.

The mountain’s proximity to other mineral-rich zones in New Jersey adds to its appeal for gemstone enthusiasts. Regular exploration of this site continues to yield interesting specimens for both amateur and experienced collectors.

Pompton River

The Pompton River runs through Passaic County in northern New Jersey. It forms when the Ramapo and Pequannock Rivers join together near Pompton Lakes and stretches about 8 miles before flowing into the Passaic River.

This river has special geology because it connects to the Ramapo Mountains and contains materials left by glaciers from the Pleistocene era. Water flowing through these diverse rock formations helps expose minerals over time.

You can search for labradorite along the riverbanks. Look in areas where the water slows down, as heavier minerals tend to settle there. Shallow spots with gravel bars are particularly good places to search.

Many rockhounds bring small shovels and screens to sift through river sediment. The best hunting times are typically spring and fall, when water levels are moderate and allow safer access to more areas of the riverbed.

Snake Hill

Snake Hill is a large rock formation in Secaucus, rising from the flat lands around the Hackensack River. This unique hill stands out in Hudson County’s Laurel Hill County Park.

The hill formed about 200 million years ago when hot magma pushed up through Earth’s crust. This created a diabase rock structure that now interests geologists and rockhounds alike.

Years of quarrying at Snake Hill have cut into the rock, revealing different layers that were hidden before. These exposed areas give gem hunters better chances to find minerals like labradorite.

For best results, look along the quarried rock faces where deeper layers are visible. Focus on areas with dark igneous rock, as labradorite typically forms in this type of stone. The park offers good access to these rockhounding spots throughout the year.

Places Labradorite has been found by County

After discussing our top picks, we wanted to discuss the other places on our list. Below is a list of the additional locations along with a breakdown of each place by county.

| County | Location |

| Sussex | Franklin Mine |

| Sussex | Sterling Hill Mine |

| Somerset | Millington Quarry |

| Passaic | Paterson |

| Union | Houdaille Quarry |

| Essex | Upper Montclair |

| Sussex | Emerald Cave |

| Sussex | Glenwood Creek Cave |

| Sussex | McAfee Caves |

| Sussex | Glenwood Indian Cave |

| Monmouth | Big Brook Preserve |

| Monmouth | Ramanessin Brook |

| Middlesex | Sayreville |

| Cape May | Higbee Beach |

| Morris | Stirling |

| Cape May | Cape May Beaches |

| Sussex | Clove Brook |

| Sussex | Montague |

| Morris | Rockaway Township |