From forests to beaches, Oregon has food growing naturally all around us. Learning about these plants helps you connect with nature while finding tasty treats.

Foraging is the act of searching for wild food in your environment. It brings the excitement of a scavenger hunt together with the satisfaction of eating what you find. Even beginners can learn to identify several safe plants to eat.

Safety must come first when collecting wild plants. Never eat something unless you are 100% sure what it is. Take time to learn proper identification before you start picking anything.

The Pacific Northwest climate creates perfect growing conditions for many edible plants. Berries, nuts, and leafy greens grow abundantly throughout Oregon. You might be surprised by how many familiar foods are growing wild near your home.

Let’s explore some common edible plants you can find while hiking or even walking through your neighborhood in Oregon. These plants appear during different seasons, so you can forage all year round.

What We Cover In This Article:

- The Edible Plants Found in the State

- Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

- How to Get the Best Results Foraging

- Where to Find Forageables in the State

- Peak Foraging Seasons

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

The Edible Plants Found in the State

Wild plants found across the state can add fresh, seasonal ingredients to your meals:

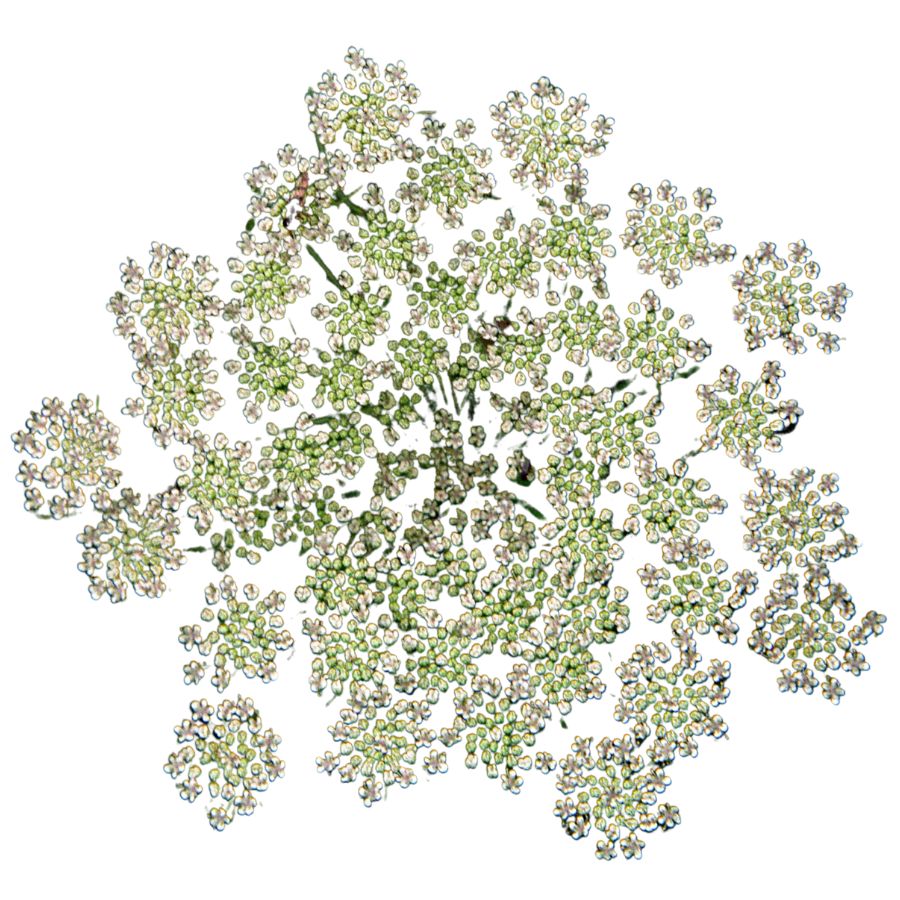

Salal (Gaultheria shallon)

Salal grows as a short, woody shrub with glossy oval leaves that shine dark green year-round. Its small, pink, bell-shaped flowers transform into dark purple berries that taste like a mix of blueberries and mild apple.

The berries grow in clusters and can be picked from July through September. Each berry contains numerous tiny seeds that add a pleasant crunch when eaten fresh.

Native peoples of the Pacific Northwest traditionally dried salal berries into cakes for winter food. The leaves were used to flavor other foods during cooking.

When foraging, look for leathery, egg-shaped leaves with pointed tips. No poisonous lookalikes exist, making salal a safe choice for beginning foragers.

The berries can be eaten raw, made into jam, or used in pies and other desserts.

Huckleberry (Vaccinium parvifolium)

Small red berries hang like tiny lanterns from the bright green branches of red huckleberry shrubs. These deciduous bushes grow up to 13 feet tall and prefer rotting wood or stumps as their growing base.

When eaten fresh, the berries burst with a tangy sweet flavor that many people prefer over commercial berries. Their bright red color makes them easy to spot among the green foliage.

Each berry contains several small seeds and provides a good source of vitamin C. Native Americans valued huckleberries as both food and medicine.

Huckleberries might be confused with red elderberries, which are toxic when raw. The key difference is that huckleberries grow individually while elderberries grow in clusters.

Only the berries are edible – avoid eating the leaves or stems. They taste great in pancakes, muffins, jams, and pies.

Pacific Crabapple (Malus fusca)

Tart and crisp, the Pacific crabapple grows wild along stream banks and wet areas throughout the Northwest coast. The tree reaches 30-40 feet tall with oval, serrated leaves and produces clusters of white to pink blossoms in spring.

The fruit resembles tiny apples, typically 1/2 to 1 inch across, turning yellowish-red when ripe. Though too sour for most people to enjoy raw, cooking transforms them into delicious jellies and preserves.

Pacific crabapples can be identified by their small size and the five-pointed star pattern of seeds inside when cut horizontally. No dangerous lookalikes exist in their native range.

These fruits contain high levels of pectin, making them perfect for jams without adding commercial thickeners. Indigenous peoples traditionally harvested and stored them in water or oil to reduce their tartness before eating.

Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus)

Thimbleberry is a native shrub that produces bright red, hollow berries with a seedy, melt-in-your-mouth texture. You can eat them raw, but they’re often used in jams and desserts because they fall apart easily.

The leaves are soft and wide with five deep lobes, unlike the more jagged or compound leaves of black raspberry or blackberry. Be cautious of misidentifying it with red raspberry, which has thorny stems and smaller, firmer fruit.

There’s no commercial thimbleberry farming because the fruit is too fragile to ship.

Thimbleberry has no thorns, which makes harvesting less painful compared to other berries in the same family. The plant’s white, five-petaled flowers are another clue you’ve found the right thing.

Don’t eat the leaves or stems; they aren’t toxic, but they’re not used for food.

Oregon grape (Mahonia aquifolium)

Oregon grape grows in low, woody clusters and has spiny, holly-like leaves with a waxy sheen. The berries are a deep blue with dusty coatings and grow in tight bunches, making them easy to gather when ripe.

The berries are tart and slightly bitter, with a texture similar to a small blueberry but firmer and more seedy. They’re most often cooked down into jelly, syrup, or wine, since eating them raw can be unpleasant due to their intense astringency.

It’s easy to mistake Oregon grape for holly or barberry, but holly lacks edible berries and barberry usually has single berries rather than clusters. The leaf shape might be similar, but Oregon grape leaves grow in paired leaflets along a central stem, not individually.

Only the berries are edible—leave the leaves, bark, and roots alone. Some people try to chew the seeds, but they’re woody and not worth the effort.

Nodding onion (Allium cernuum)

When you come across nodding onions, you’ll notice the drooping flower heads perched on tall, slender stalks. The narrow, grass-like leaves and the pinkish-white blossoms help distinguish them from toxic lookalikes like death camas, which lacks the onion smell when crushed.

You can eat the leaves, bulbs, and flowers, all of which carry a strong onion flavor with a slightly sweet finish. The texture is crisp when raw and softens nicely when sautéed or added to soups.

One popular way to use nodding onions is to mince the greens into spreads or salads, or grill the bulbs whole like scallions. Pickling the flower buds is another method that preserves their tang and adds punch to charcuterie boards.

Avoid harvesting from roadsides or polluted areas, since these plants can absorb contaminants through their roots. While edible, the plant loses flavor quickly after picking, so it’s best to use it fresh whenever possible.

Wild Rose (Rosa nutkana)

Delicate pink flowers with five petals and a sweet fragrance mark the Nootka rose in late spring. After flowering, the plant develops bright red seed pods called rose hips, which grow up to an inch in diameter.

The thorny stems and compound leaves with toothed edges help identify this native plant. Rose hips taste slightly sweet and tangy with a bit of tartness similar to crabapples.

Wild roses have no toxic lookalikes, though blackberry bushes might appear similar when not in bloom. The difference lies in the leaves – rose leaves are compound with 5-7 leaflets while blackberry leaves grow in groups of three or five.

Rose hips contain more vitamin C than oranges by weight. Before using, cut them open and remove the irritating hairy seeds inside.

People use rose hips to make tea, syrup, jam, and even wine. The petals are also edible and make beautiful garnishes.

Wild Strawberry (Fragaria vesca)

Nestled close to the ground on slender stems, wild strawberries produce fruits much smaller than store-bought varieties but with far more intense flavor. The plants spread by runners, creating patches of three-parted leaves with toothed edges.

The berries, when fully ripe, are completely red with no white areas and pull easily from the stem. Their taste combines sweetness with a perfumed quality that commercial strawberries lack.

Wild strawberries are completely edible – fruits, leaves, and even flowers. The leaves make a pleasant tea that was traditionally used to treat digestive problems.

You can identify true wild strawberries by their white flowers and fruits that have seeds on the outside. False strawberry, a harmless but bland lookalike, has yellow flowers.

Enjoy wild strawberries fresh, in desserts, or preserved as jam. Their small size makes harvesting time-consuming but worth the effort.

Wood Sorrel (Oxalis spp.)

Wood sorrel is easy to spot with its clover-like leaves, delicate flowers, and sour flavor. It often goes by names like sourgrass and shamrock, although it is not the same as the traditional Irish shamrock.

Wood sorrel can be mistaken for true clovers, which do not have the same sour taste. Always check the leaf shape and flavor before eating, because wood sorrel leaves are distinctly heart-shaped and more delicate.

The leaves, flowers, and seed pods of wood sorrel are all edible and have a sharp, lemony taste that makes them a refreshing trail snack. You can also toss them into salads or use them as a garnish to brighten up a dish with their tartness.

While wood sorrel is generally safe in small amounts, it does contain oxalic acid, so it is best not to eat large quantities. Some people also like to brew the leaves into a light, tangy tea, adding another way to enjoy this common and flavorful wild plant.

Curly dock (Rumex crispus)

Curly dock, sometimes called yellow dock, is easy to spot once you know what to look for. It has long, wavy-edged leaves that form a rosette at the base, with tall stalks that eventually turn rusty brown as seeds mature.

The young leaves are edible and often cooked to mellow out their sharp, lemony taste, which can be too strong when eaten raw. You can also dry and powder the seeds to use as a flour supplement, although they are tiny and take some effort to prepare.

Curly dock has some lookalikes, like other types of dock and sorrel, but its heavily crinkled leaf edges and thick taproot help it stand out. Be careful not to confuse it with plants like wild rhubarb, which can have toxic parts if misidentified.

Besides being edible, curly dock has a history of being used in homemade remedies for skin irritation. The roots are not eaten raw because they are tough and contain compounds that can upset your stomach if you are not careful.

Red Clover (Trifolium pratense)

Red clover is also called wild clover or purple clover, and it grows in open areas with lots of sunlight. The round flower heads are a soft pinkish red, and the leaves have a pale crescent near the center.

The flower heads are the part most often gathered, and they can be eaten raw or dried for later use. Some people steep them in hot water for a mild, slightly sweet tea with a grassy flavor.

If you’re collecting flowers, make sure not to confuse them with crown vetch, which grows in similar spots but has more elongated, pea-like flowers. Crown vetch isn’t safe to eat, and it usually has a vine-like growth pattern that red clover doesn’t.

Red clover flowers can be tossed into salads or baked into muffins and breads for color and a hint of sweetness. The leaves are sometimes eaten too, but they tend to be tougher and more bitter.

Wild leek (Allium tricoccum)

Known as wild leek, ramp, or ramson, this flavorful plant is famous for its broad green leaves and slender white stems. It grows low to the ground and gives off a strong onion-like scent when bruised, which can help you tell it apart from toxic lookalikes like lily of the valley.

If you give it a taste, you will notice a bold mix of onion and garlic flavors, with a tender texture that softens even more when cooked. People often sauté the leaves and stems, pickle the bulbs, or blend them into pestos and soups.

The entire plant can be used for cooking, but the leaves and bulbs are the most prized parts. It is important not to confuse it with similar-looking plants that do not have the signature onion smell when crushed.

Wild leek populations have declined in some areas because of overharvesting, so it is a good idea to only take a few from any given patch. When harvested thoughtfully, these vibrant greens can add a punch of flavor to just about anything you make.

Chickweed (Stellaria media)

Chickweed, sometimes called satin flower or starweed, is a small, low-growing plant with delicate white star-shaped flowers and bright green leaves. The leaves are oval, pointed at the tip, and often grow in pairs along a slender, somewhat weak-looking stem.

When gathering chickweed, watch out for lookalikes like scarlet pimpernel, which has similar leaves but orange flowers instead of white. A key detail to check is the fine line of hairs that runs along one side of chickweed’s stem, a feature the dangerous lookalikes do not have.

The young leaves, tender stems, and flowers of chickweed are all edible, offering a mild, slightly grassy flavor with a crisp texture. You can toss it fresh into salads, blend it into pestos, or lightly wilt it into soups and stir-fries for a fresh green boost.

Aside from being a food plant, chickweed has been used traditionally in poultices and salves to help soothe skin irritations. Always make sure the plant is positively identified before eating, since mistaking it for a toxic lookalike could cause serious issues.

Catnip (Nepeta cataria)

Catnip grows as a bushy perennial herb with heart-shaped, grayish-green leaves that have scalloped edges. The plant produces small white flowers with purple spots, reaching heights of 2-3 feet when mature.

Most people recognize catnip for its effect on cats, but humans have used it for centuries as a calming tea. The leaves and flowering tops are the edible parts, offering a minty flavor with slight lemon notes.

Identification is simple once you recognize the square stem typical of the mint family and the distinctive scent when leaves are crushed. While catnip resembles other mint family plants, its strong aroma sets it apart.

Harvest the leaves before flowering for the best flavor. Catnip can be dried for tea, added fresh to salads, or used as a seasoning in certain dishes. Many herbalists value catnip for its potential to ease digestion and promote relaxation.

Gooseberry (Ribes spp.)

With their translucent skin and distinctive veining, gooseberries hang like jewels on thorny shrubs. These tart berries range in color from green to red to purple, depending on the variety and ripeness.

Gooseberry bushes grow to about 3-5 feet tall and feature lobed leaves similar to currants. The berries themselves contain tiny seeds and offer a complex flavor that balances sweetness and acidity.

When foraging, look for the thorny stems and the characteristic ribbed berries that grow individually rather than in clusters. Wild gooseberries are smaller than cultivated varieties but often more flavorful.

No toxic lookalikes exist for gooseberries, making them relatively safe for novice foragers. The entire berry is edible and can be eaten raw when ripe or cooked into preserves, pies, and sauces. These berries contain significant vitamin C and antioxidants, making them both delicious and nutritious.

Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides)

Sea buckthorn produces vibrant orange berries that cling tightly to thorny branches, creating a striking display against silver-green leaves. This shrub thrives in coastal areas and harsh environments, developing an extensive root system that helps prevent soil erosion.

The berries have an unusual, tangy flavor often described as a mix of pineapple and citrus. Each small berry contains a single seed and abundant juice that stains fingers when harvested.

When identifying sea buckthorn, look for the narrow, elongated leaves with silvery undersides and the distinct bright orange berries that remain on the plant through winter. The thorny nature of the plant makes harvesting challenging, with many foragers freezing branches before removing berries.

Sea buckthorn berries contain exceptional levels of vitamin C and oils beneficial for skin health. These nutritional powerhouses can be made into juice, jam, or oil, though their intense tartness typically requires sweetening or blending with other ingredients.

Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia)

Serviceberry trees burst with clusters of white flowers in early spring before developing sweet purple-blue fruits that resemble blueberries. The berries have a subtle almond undertone thanks to small seeds that contain trace amounts of cyanide compounds, though these are safe to consume in normal quantities.

The multi-stemmed shrubs or small trees grow up to 15-25 feet tall with oval leaves that turn brilliant orange-red in fall. Serviceberries ripen in early summer, often signaling the beginning of berry season.

Birds love these fruits, so quick harvesting is essential. When foraging, ensure you’ve correctly identified serviceberry by noting the smooth gray bark and fine-toothed leaves. Some people confuse them with chokecherries, which have more elongated fruits in drooping clusters.

Only the berries are edible, perfect for eating fresh, drying like raisins, or using in pies, jams, and muffins. Serviceberries have long been important to indigenous peoples across North America, providing essential nutrition and natural sweetness.

Field Garlic (Allium vineale)

The slender, hollow leaves of field garlic rise from underground bulbs, appearing like thin grass but revealing their true nature through a distinct garlic aroma when crushed. This wild allium grows in clusters, often in lawns, meadows, and along trails.

Every part of field garlic can be eaten, from the underground bulbs to the leaves and even the bulbils that form in place of flowers. The flavor is milder than cultivated garlic but more potent than chives.

Field garlic is sometimes confused with toxic lookalikes such as death camas or star-of-Bethlehem, but these plants lack the characteristic garlic smell. Always crush a leaf to check for the unmistakable allium scent before harvesting.

Foragers prize field garlic for its year-round availability, even in winter when other wild edibles are scarce. The green tops make excellent additions to salads, soups, and compound butters, while the small bulbs can replace garlic in any recipe.

Mallow (Malva spp.)

Mallow, often called common mallow or cheeseweed, grows low to the ground and spreads with round, crinkled leaves that look a bit like tiny lily pads. It produces small pale purple or pink flowers with five delicate petals, and the seed pods are shaped like little green wheels.

The leaves, flowers, and immature seed pods of mallow are all edible, offering a mild, slightly sweet flavor and a soft, somewhat mucilaginous texture. Some people add the leaves to salads, toss them into soups for thickening, or quickly sauté them with garlic for a simple side dish.

When gathering mallow, make sure you do not confuse it with young deadly nightshade plants, which can sometimes grow in similar weedy areas but have very different flower and fruit structures. Mallow is safe to eat, but it tends to absorb pollutants from the soil, so be cautious about harvesting from roadsides or contaminated areas.

An interesting thing about mallow is that it was traditionally used for soothing sore throats and irritated skin because of its natural slimy quality. If you are foraging for food and medicine, mallow is a versatile and easy plant to start with once you are confident in your identification.

Violet (Viola spp.)

Delicate heart-shaped leaves and cheerful five-petaled flowers make violets one of the most recognizable wild edibles in meadows and woodlands. These low-growing plants rarely exceed 6 inches in height and form loose clusters in partly shaded areas.

Both the leaves and flowers are edible, with a mild, slightly sweet flavor that works well in salads or as garnishes. The flowers contain vitamin C and have a pleasant, subtle perfume that has made them popular in candied form.

Violets have no dangerous lookalikes, though they might be confused with other violet family members, all of which are safe to eat. The key identifying features include basal leaves growing directly from the ground and distinctive flowers with five petals, the lower one often extending into a spur.

For the best flavor, harvest young leaves in spring before the weather turns hot. The flowers make beautiful decorations for desserts or can be made into syrup, jelly, or tea. Traditional herbalists have long valued violet leaves for their mild expectorant properties and soothing effect on irritated tissues.

Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

There are plenty of wild edibles to choose from, but some toxic native plants closely resemble them. Mistaking the wrong one can lead to severe illness or even death, so it’s important to know exactly what you’re picking.

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild carrot (Daucus carota)

Poison hemlock is a tall plant with lacy leaves and umbrella-like clusters of tiny white flowers. It has smooth, hollow stems with purple blotches and grows in sunny places like roadsides, meadows, and stream banks.

Unlike wild carrot, which has hairy stems and a dark central floret, poison hemlock has a musty odor and no flower center spot. It’s extremely toxic; just a small amount can be fatal, and even touching the sap can irritate the skin.

Water Hemlock (Cicuta spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) or wild celery (Apium spp.)

Water hemlock is a tall, branching plant with umbrella-shaped clusters of small white flowers. It grows in wet places like stream banks, marshes, and ditches, with stems that often show purple streaks or spots.

It can be confused with wild parsnip or wild celery, but its thick, hollow roots have internal chambers and release a yellow, foul-smelling sap when cut. Water hemlock is the most toxic plant in North America, and just a small amount can cause seizures, respiratory failure, and death.

False Hellebore (Veratrum viride)

Often mistaken for: Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

False hellebore is a tall plant with broad, pleated green leaves that grow in a spiral from the base, often appearing early in spring. It grows in moist woods, meadows, and along streams.

It’s commonly mistaken for ramps, but ramps have a strong onion or garlic smell, while false hellebore is odorless and later grows a tall flower stalk. The plant is highly toxic, and eating any part can cause nausea, a slowed heart rate, and even death due to its alkaloids that affect the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Death Camas (Zigadenus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild onion or wild garlic (Allium spp.)

Death camas is a slender, grass-like plant that grows from underground bulbs and is found in open woods, meadows, and grassy hillsides. It has small, cream-colored flowers in loose clusters atop a tall stalk.

It’s often confused with wild onion or wild garlic due to their similar narrow leaves and habitats, but only Allium plants have a strong onion or garlic scent, while death camas has none. The plant is extremely poisonous, especially the bulbs, and even a small amount can cause nausea, vomiting, a slowed heartbeat, and potentially fatal respiratory failure.

Buckthorn Berries (Rhamnus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Elderberries (Sambucus spp.)

Buckthorn is a shrub or small tree often found along woodland edges, roadsides, and disturbed areas. It produces small, round berries that ripen to dark purple or black and usually grow in loose clusters.

These berries are sometimes mistaken for elderberries and other wild fruits, which also grow in dark clusters, but elderberries form flat-topped clusters on reddish stems while buckthorn berries are more scattered. Buckthorn berries are unsafe to eat as they contain compounds that can cause cramping, vomiting, and diarrhea, and large amounts may lead to dehydration and serious digestive problems.

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Mayapple is a low-growing plant found in shady forests and woodland clearings. It has large, umbrella-like leaves and produces a single pale fruit hidden beneath the foliage.

The unripe fruit resembles a small green grape, causing confusion with wild grapes, which grow in woody clusters on vines. All parts of the mayapple are toxic except the fully ripe, yellow fruit, which is only safe in small amounts. Eating unripe fruit or other parts can lead to nausea, vomiting, and severe dehydration.

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Virginia creeper is a fast-growing vine found on fences, trees, and forest edges. It has five leaflets per stem and produces small, bluish-purple berries from late summer to fall.

It’s often confused with wild grapes since both are climbing vines with similar berries, but grapevines have large, lobed single leaves and tighter fruit clusters. Virginia creeper’s berries are toxic to humans and contain oxalate crystals that can cause nausea, vomiting, and throat irritation.

Castor Bean (Ricinus communis)

Often mistaken for: Wild rhubarb (Rumex spp. or Rheum spp.)

Castor bean is a bold plant with large, lobed leaves and tall red or green stalks, often found in gardens, along roadsides, and in disturbed areas in warmer regions in the US. Its red-tinged stems and overall size can resemble wild rhubarb to the untrained eye.

Unlike rhubarb, castor bean plants produce spiny seed pods containing glossy, mottled seeds that are extremely toxic. These seeds contain ricin, a deadly compound even in small amounts. While all parts of the plant are toxic, the seeds are especially dangerous and should never be handled or ingested.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

How to Get the Best Results Foraging

Safety should always come first when it comes to foraging. Whether you’re in a rural forest or a suburban greenbelt, knowing how to harvest wild foods properly is a key part of staying safe and respectful in the field.

Always Confirm Plant ID Before You Harvest Anything

Knowing exactly what you’re picking is the most important part of safe foraging. Some edible plants have nearly identical toxic lookalikes, and a wrong guess can make you seriously sick.

Use more than one reliable source to confirm your ID, like field guides, apps, and trusted websites. Pay close attention to small details. Things like leaf shape, stem texture, and how the flowers or fruits are arranged all matter.

Not All Edible Plants Are Safe to Eat Whole

Just because a plant is edible doesn’t mean every part of it is safe. Some plants have leaves, stems, or seeds that can be toxic if eaten raw or prepared the wrong way.

For example, pokeweed is only safe when young and properly cooked, while elderberries need to be heated before eating. Rhubarb stems are fine, but the leaves are poisonous. Always look up which parts are edible and how they should be handled.

Avoid Foraging in Polluted or Contaminated Areas

Where you forage matters just as much as what you pick. Plants growing near roads, buildings, or farmland might be coated in chemicals or growing in polluted soil.

Even safe plants can take in harmful substances from the air, water, or ground. Stick to clean, natural areas like forests, local parks that allow foraging, or your own yard when possible.

Don’t Harvest More Than What You Need

When you forage, take only what you plan to use. Overharvesting can hurt local plant populations and reduce future growth in that area.

Leaving plenty behind helps plants reproduce and supports wildlife that depends on them. It also ensures other foragers have a chance to enjoy the same resources.

Protect Yourself and Your Finds with Proper Foraging Gear

Having the right tools makes foraging easier and safer. Gloves protect your hands from irritants like stinging nettle, and a good knife or scissors lets you harvest cleanly without damaging the plant.

Use a basket or breathable bag to carry what you collect. Plastic bags hold too much moisture and can cause your greens to spoil before you get home.

This forager’s toolkit covers the essentials for any level of experience.

Watch for Allergic Reactions When Trying New Wild Foods

Even if a wild plant is safe to eat, your body might react to it in unexpected ways. It’s best to try a small amount first and wait to see how you feel.

Be extra careful with kids or anyone who has allergies. A plant that’s harmless for one person could cause a reaction in someone else.

Check Local Rules Before Foraging on Any Land

Before you start foraging, make sure you know the rules for the area you’re in. What’s allowed in one spot might be completely off-limits just a few miles away.

Some public lands permit limited foraging, while others, like national parks, usually don’t allow it at all. If you’re on private property, always get permission first.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

Where to Find Forageables in the State

There is a range of foraging spots where edible plants grow naturally and often in abundance:

| Plant | Locations |

|---|---|

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria vesca, Fragaria virginiana) | – Sauvie Island Wildlife Area, near Portland – Mount Pisgah Arboretum, Eugene – Cascade Head Preserve, near Lincoln City |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | – Fields near Hermiston – Agricultural lands around Klamath Falls – Roadside areas in Corvallis |

| Mulberry (Morus spp.) | – Residential areas in Medford – Urban parks in Salem – Community gardens in Eugene |

| Oregon Grape (Mahonia aquifolium) | – Terwilliger Parkway, Portland – Forest Park, Portland – Mount Tabor Park, Portland |

| Purslane (Portulaca oleracea) | – Community gardens in Bend – Urban sidewalks in Ashland – Vacant lots in Grants Pass |

| Wild Rose (Rosa nutkana) | – Alton Baker Park, Eugene – Tryon Creek State Natural Area, Portland – Hendricks Park, Eugene |

| Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) | – Silver Falls State Park, near Silverton – Mary’s Peak, near Philomath – Tillamook State Forest, near Tillamook |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | – Lawns in downtown Portland – Meadows in the Willamette Valley – Roadside areas in Bend |

| Good King Henry (Chenopodium bonus-henricus) | – Community gardens in Ashland – Abandoned lots in Eugene – Old homesteads near Pendleton |

| Blackberry (Rubus armeniacus, Rubus ursinus) | – Banks-Vernonia Trail, near Banks – Alsea Falls, near Alsea – Sandy River Delta, near Troutdale |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis oregana) | – Hoyt Arboretum, Portland – Cape Perpetua, near Yachats – Forested Coast Range areas |

| Red Huckleberry (Vaccinium parvifolium) | – Mount Hood foothills near Rhododendron – Coastal forest near Yachats – Forest edge near Reedsport |

| Wild Mint (Mentha arvensis) | – Wetlands near Springfield – Along Deschutes River, near Bend – Riparian areas in Umpqua Valley |

| Wild Leek (Allium tricoccum) | – Wallowa Mountains near Enterprise – Moist woods near La Grande – Blue Mountains foothills |

| Chicory (Cichorium intybus) | – Roadsides near Salem – Fields around McMinnville – Open areas in the Rogue Valley |

| Catnip (Nepeta cataria) | – Gardens in Ashland – Urban areas in Eugene – Community plots in Corvallis |

| Pacific Crabapple (Malus fusca) | – Wetlands near Astoria – Columbia River edge near The Dalles – Coastal areas near Coos Bay |

| Mallow (Malva spp.) | – Vacant lots in Portland – Fields near Medford – Roadside areas in Albany |

| Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) | – Roadsides in Eugene – Fields near Salem – Urban lots in Portland |

| Fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium) | – Burned Cascade Range areas – Meadows near Sisters – Forest edge near Mt. Jefferson |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia) | – Hillsides near Pendleton – Ochoco Mountains slopes – Foothills near Baker City |

| Clover (Trifolium pratense, T. repens) | – Lawns in Eugene – Pastures near Corvallis – Fields around Grants Pass |

| Bigleaf Maple (Acer macrophyllum) | – Forests near Eugene – Coast Range woodlands – Along Willamette River near Albany |

| Gooseberry (Ribes spp.) | – Siskiyou Mountains slopes – Forest near Roseburg – Hills near Hood River |

| Borage (Borago officinalis) | – Community gardens in Portland – Urban farms in Eugene – Backyard gardens in Ashland |

| Salal (Gaultheria shallon) | – Coastal forest near Newport – Tillamook State Forest understory – Coast Range woodlands |

| Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) | – Riparian zones near La Grande – Blue Mountain edges – Streams near Baker City |

| Violet (Viola spp.) | – Portland park shade – Forest floors near Eugene – Corvallis woodlands |

| Wild Mustard (Brassica spp.) | – Fields near Salem – Willamette Valley roadsides – Open ground around Medford |

| Amaranth (Amaranthus retroflexus) | – Hermiston fields – Disturbed soil in Bend – Vacant lots in Eugene |

| Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | – Portland forest paths – Shaded trails near Corvallis – Eugene woodland patches |

| Daisy (Bellis perennis) | – Lawns in Salem – Portland city parks – Ashland gardens |

| Red Currant (Ribes rubrum) | – Gardens in Eugene – Portland urban areas – Corvallis community plots |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | – Ashland gardens – Lawns in Eugene – Portland shaded areas |

| Peppermint (Mentha × piperita) | – Willamette River banks near Salem – Springfield wetlands – Umpqua Valley streamsides |

| Narrowleaf Plantain (Plantago lanceolata) | – Corvallis fields – Roadsides in Bend – Medford open areas |

| Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) | – Coastal dunes near Florence – Astoria seaside lots – Beaches near Coos Bay |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | – Fields near Eugene – Salem roadside shoulders – Open areas near Grants Pass |

| Wild Cherry (Prunus avium) | – Portland urban forests – Coast Range woodlands – Columbia River banks near Hood River |

Peak Foraging Seasons

Different edible plants grow at different times of year, depending on the season and weather. Timing your search makes all the difference.

Spring

Spring brings a fresh wave of wild edible plants as the ground thaws and new growth begins:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Wild leek (Allium tricoccum) | March–May | Moist, rich woodland soil |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | March–May | Open grassy fields after rain |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | March–May | Cool, shaded garden edges |

| Lamb’s quarters (Chenopodium album) | April–May | Sunny disturbed soils |

| Shepherd’s purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris) | March–May | Cool meadows and trails |

| Wood sorrel (Oxalis oregana) | March–May | Shady, mossy forest floors |

| Violet (Viola spp.) | March–May | Moist woodland areas |

| Catnip (Nepeta cataria) | April–May | Sunny edges of fields or trails |

| Good King Henry (Chenopodium bonus-henricus) | April–May | Rich garden soil |

| Wild mustard (Brassica spp.) | April–May | Sunny disturbed ground |

Summer

Summer is a peak season for foraging, with fruits, flowers, and greens growing in full force:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Blackberry (Rubus armeniacus, Rubus ursinus) | July–August | Sunny forest edges and roadsides |

| Red huckleberry (Vaccinium parvifolium) | June–August | Shaded coniferous forest slopes |

| Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) | June–July | Partially shaded woodland edges |

| Salal (Gaultheria shallon) | June–August | Coastal forest undergrowth |

| Mulberry (Morus spp.) | June–July | Warm, sunny backyards and roadsides |

| Wild strawberry (Fragaria vesca, Fragaria virginiana) | May–July | Open meadows and trail edges |

| Pacific crabapple (Malus fusca) | July–August | Moist lowlands or near streams |

| Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) | July–August | Open woodland and thickets |

| Wild rose (Rosa nutkana) – petals | May–June | Dry sunny hillsides and roadsides |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia) | June–July | Dry slopes and open forests |

Fall

As temperatures drop, many edible plants shift underground or produce their last harvests:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Oregon grape (Mahonia aquifolium) | September–October | Shaded hillsides and forest edges |

| Peppermint (Mentha × piperita) | August–October | Cool, damp soil near streams |

| Clover (Trifolium pratense, T. repens) | September–October | Moist sunny meadows |

| Curly dock (Rumex crispus) | September–November | Moist low fields and ditches |

| Red currant (Ribes rubrum) | September–October | Cool moist woodland clearings |

| Wild cherry (Prunus avium) | September–October | Open woodlands or backyards |

| Gooseberry (Ribes spp.) | August–September | Cool forested or riparian areas |

| Field garlic (Allium vineale) | September–October | Grassy meadows and sunny slopes |

| Nodding onion (Allium cernuum) | August–September | Open woods and dry meadows |

| Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) | September–October | Dry, sunny shrublands |

Winter

Winter foraging is limited but still possible, with hardy plants and preserved growth holding on through the cold:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | December–February | Dry meadows and roadsides |

| Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) | December–February | Sunny, disturbed sites near coast |

| Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | January–February | Shaded trails and woodland paths |

| Mallow (Malva spp.) | December–February | Urban lots and disturbed fields |

| Chicory (Cichorium intybus) | January–February | Sunny open fields and roadsides |

| Borage (Borago officinalis) | December–February | Cool garden beds and disturbed sites |

| Alexanders (Smyrnium olusatrum) | January–February | Shaded trails and hedgerows |

| Narrowleaf plantain (Plantago lanceolata) | December–February | Disturbed lawns and field edges |

| Daisy (Bellis perennis) | January–February | Open grassy fields |

| Sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella) | December–February | Acidic soils in open areas |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.