Nevada offers plenty of natural food options for anyone willing to look. Our state has different landscapes where wild foods grow. The desert areas, mountains, and water sources all hold tasty treats.

You can discover pine nuts in the higher elevations throughout the state. These nutritious nuts fall from pinyon pine trees in late summer and early fall. Local tribes have gathered them for thousands of years as an important food source.

Desert plants provide surprising food too. Prickly pear cactus grows its sweet fruits in many southern Nevada areas. The pads can also be eaten when prepared correctly.

Wild onions and garlic pop up in spring across wetter areas of Nevada. They add flavor to meals and are easy to spot by their distinctive smell. Look for them near streams and in mountain meadows.

Berries grow naturally in several parts of our state. Elderberries and wild strawberries thrive in mountain regions with good moisture. Always learn to identify them properly before eating.

Learning about local plants takes time but brings great rewards. This guide about Nevada edible plants can help you start your foraging journey.

What We Cover In This Article:

- The Edible Plants Found in the State

- Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

- How to Get the Best Results Foraging

- Where to Find Forageables in the State

- Peak Foraging Seasons

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

The Edible Plants Found in the State

Wild plants found across the state can add fresh, seasonal ingredients to your meals:

Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.)

Amaranth has broad, often reddish-tinged leaves and dense flower spikes that range from green to deep purple. You can eat both the leaves and the seeds, with the leaves tasting slightly earthy and the seeds having a nutty flavor when cooked.

Boil or sauté the young leaves like spinach, or use the seeds as a grain substitute in porridge or flatbreads. Avoid pigweed lookalikes—while related, some varieties grow in contaminated soils or accumulate nitrates, making them a risky choice.

The seeds of amaranth are tiny, round, and can be white, golden, or dark brown, depending on the variety. Cooked seeds have a slightly chewy texture and pop a bit when heated, similar to quinoa.

Amaranth leaves are more tender when young and can be eaten raw, but mature leaves need cooking to soften their fibrous texture. There’s nothing toxic in the plant itself, but overconsumption of raw leaves can irritate due to oxalates.

Beeplant (Cleome serrulata)

Beeplant grows up to three feet tall with pink to purple flowers that grow in clusters. It has fan-shaped leaves that grow in groups of three. The flowers make sweet nectar that bees and butterflies love.

You can eat the young leaves, flower buds, and seed pods of this plant. The young leaves taste a bit bitter when raw but are milder when cooked. They work well in soups or as a steamed side dish.

Native American tribes used beeplant for food and medicine. The Navajo used it to help with stomach problems. The seeds can be ground up to make flour for bread.

When looking for beeplant, check for the three-part leaves and pink-purple flowers. There aren’t any dangerous plants that look like it. Sometimes people mix it up with spider flower, which you can also eat.

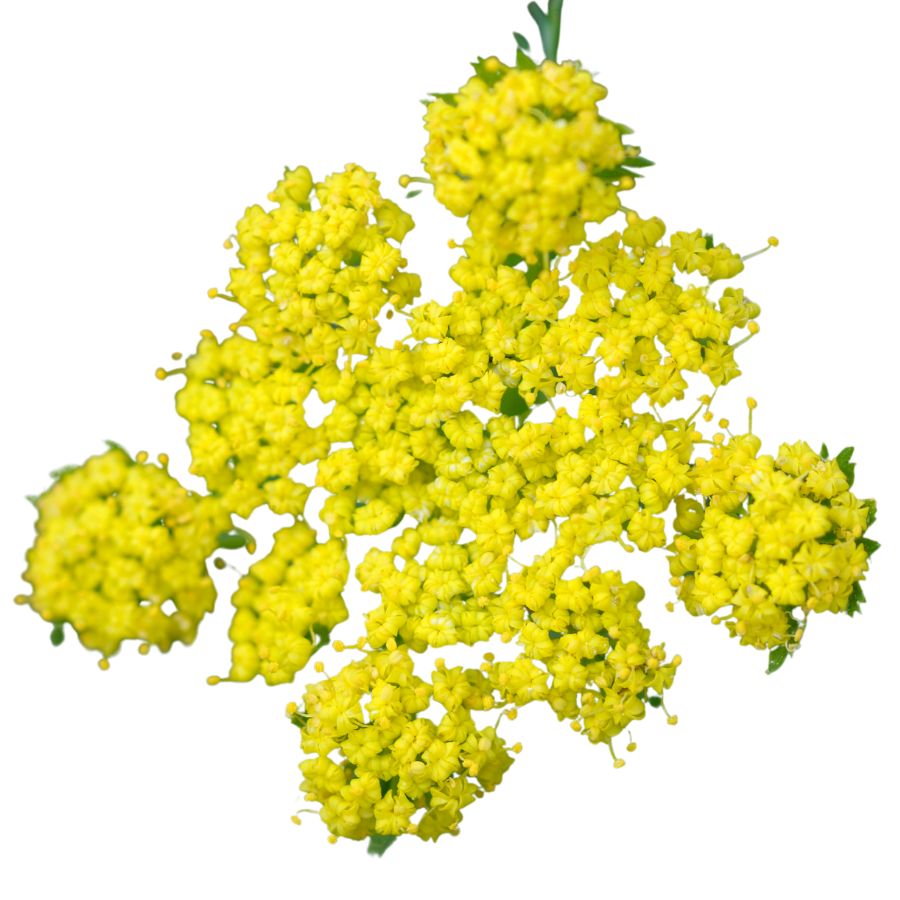

Biscuitroot (Lomatium spp.)

For thousands of years, Native Americans ate biscuitroot as an important food. This plant grows from a thick root that smells like celery when cut. It has small yellow flowers that grow in clusters shaped like umbrellas.

To find biscuitroot, look for fern-like leaves and the umbrella-shaped flower groups. The roots taste earthy and good when cooked.

Be very careful when picking this plant. Some plants in the same family can kill you, like water hemlock and poison hemlock. Make sure you know exactly what you’re picking.

You can bake, roast, or dry the root and grind it into flour. Many tribes dried the roots, ground them up, and mixed them with water to make small cakes. They baked these cakes on hot rocks.

Bitterroot (Lewisia rediviva)

Bitterroot has beautiful pink to white flowers that grow right from the ground with no visible stems or leaves. When not flowering, it’s hard to find because its leaves die back before the flowers appear.

People traditionally dug up the starchy root in spring before the plant flowered. Though its name suggests otherwise, you can remove the bitter taste with proper cooking. Native Americans carefully peeled off the brown outer layer before cooking to get rid of the bitterness.

Bitterroot contains lots of vitamin C. Native Americans and early settlers valued it as healthy food during times when food was scarce. The Flathead and Shoshone tribes would travel far for yearly bitterroot harvests.

There are no poisonous plants that look like bitterroot. But you need to know exactly where and when to look for it. The roots taste best when collected before the plant flowers.

Cattail (Typha spp.)

The brown seed head of a cattail looks like a hotdog on a stick, making it one of the easiest wild plants to spot. This plant grows in marshy areas, ponds, and along slow-moving water across North America.

You can eat almost every part of the cattail at different times of the year. In spring, the young shoots can be eaten raw or cooked like asparagus. The young flower spikes can be boiled and eaten like corn on the cob.

The roots of cattail contain starch that can be made into flour. These roots are full of carbs and were an important survival food for many native cultures.

When gathering cattail, make sure you pick from clean water areas with no pollution. No poisonous plants look like cattail, but blue flag iris sometimes grows nearby and is not safe to eat.

Chia (Salvia columbariae)

Desert chia produces small black seeds that are full of healthy omega-3 fats. This plant was an important food for native peoples in the southwestern United States. It grows low to the ground with wrinkled leaves and has small blue to purple flowers in round clusters.

Native American tribes collected the seeds by shaking the dried seed heads into baskets. When mixed with water, the seeds create a gel coating. This was valued because it helped provide energy during long trips.

Finding desert chia is pretty easy. Look for square stems (typical of mint family plants) and the distinct circular flower heads. The plant smells like sage when you crush it.

Modern research shows what native peoples already knew: chia seeds are very nutritious. They contain protein, fiber, and healthy fats. You can eat the seeds raw, add them to drinks, or grind them into flour for baking.

Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana)

Clusters of dark berries hanging from a woody shrub usually indicate chokecherries, especially when the leaves are oval with finely toothed edges. These berries turn from red to deep purple or black when they’re ready to eat.

Chokecherries are rarely eaten raw due to their bitterness, but they shine in cooked recipes like preserves, sauces, or even homemade wine. Boiling the fruit and straining it helps separate the pulp from the inedible seeds.

It’s easy to mix up chokecherries with other wild cherries, but true chokecherries have longer, narrower leaves and a more astringent taste. Avoid anything with rounder, solitary berries or a sweet scent without the signature tartness.

Their texture is slightly gritty around the pit, and the flavor improves significantly with sugar and heat. A strong astringent quality dominates the raw berry, but the processed pulp becomes rich and deeply flavored.

Currant (Ribes spp.)

Currants are small, shrubby plants that produce clusters of round berries and are often called wild currants or gooseberries, depending on the species. You can recognize them by their lobed leaves, slender stems, and berries that come in shades of red, black, or even golden yellow.

Some currant plants have lookalikes, such as certain types of nightshade, which can be toxic if eaten. To tell them apart, check the leaves and stems closely because real currants have woody stems and leaves that feel soft and slightly rough.

The berries are edible and offer a tart, slightly sweet flavor with a juicy texture that pops when you bite into them. People often use currants to make jams, jellies, syrups, and even baked goods like tarts and cakes.

While currant berries are a treat, the leaves can also be used to flavor teas, although they are not as widely eaten.

It’s important to avoid eating any berries that taste bitter or look unfamiliar, since not all wild berries are safe.

Indian Ricegrass (Achnatherum hymenoides)

Indian ricegrass grows in sandy soils across western North America. It can grow up to 2 feet tall and makes small black seeds that look like rice when cleaned. These seeds taste nutty and a bit sweet. Native Americans have eaten these seeds for thousands of years.

You can collect the seeds by bending the grass over a container and running your fingers along it. Wait until the seeds turn dark brown or black before picking them. After collecting, you’ll need to shake or blow away the outer coverings.

You can tell Indian ricegrass apart from other grasses by its curved seed tips and how it grows in clumps. The seeds can be ground into flour for bread or cooked whole like rice. They are full of protein and fiber, making them good wild food.

Lambsquarters (Chenopodium album)

Lamb’s quarters, also called wild spinach and pigweed, has soft green leaves that often look dusted with a white, powdery coating. The leaves are shaped a little like goose feet, with slightly jagged edges and a smooth underside that feels almost velvety when you touch it.

A few plants can be confused with lamb’s quarters, like some types of nightshade, but true lamb’s quarters never have berries and its leaves are usually coated in that distinctive white bloom. Always check that the stems are grooved and not round and smooth like the poisonous lookalikes.

When you taste lamb’s quarters, you will notice it has a mild, slightly nutty flavor that gets richer when cooked. The young leaves, tender stems, and even the seeds are all edible, but you should avoid eating the older stems because they become tough and stringy.

People often sauté lamb’s quarters like spinach, blend it into smoothies, or dry the leaves for later use in soups and stews. It is also rich in oxalates, so you will want to cook it before eating large amounts to avoid any problems.

Manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.)

Manzanita is a bush with smooth red bark and tough, oval leaves that stay green all year. It grows small, bell-shaped flowers that turn into red or brown berries. These berries look like tiny apples, which is why they’re called “manzanita” – Spanish for “little apple.”

The berries are the part you can eat, though they’re dry and have big seeds inside. You can eat them raw, but many people soak them in water to make a tangy drink. Native tribes used the berries to make cider and meal.

When picking manzanita berries, choose ones that come off the branch easily. Don’t pick green ones – they’re not ripe yet. The berries have vitamin C and were used by native people to help with upset stomachs. The plant’s special bark makes it easy to spot in the wild.

Mariposa Lily (Calochortus spp.)

Mariposa lilies have beautiful cup-shaped flowers with three petals. These petals often have spots that look like butterfly wings. In fact, “mariposa” means butterfly in Spanish. The flowers come in many colors from white to purple.

The bulbs that grow underground are the part you can eat. When cooked, they taste nutty, kind of like chestnuts. Native Americans would dig up these bulbs, then roast or boil them for food.

You can spot Mariposa lilies by looking for their three-petaled flowers and thin, grass-like leaves. Be careful when digging up bulbs – many Mariposa lily types are becoming rare. If you do collect them, take just a few from places where there are many, and replant the small bulbs so more can grow later.

Mesquite (Prosopis spp.)

Mesquite produces long seed pods that are edible when ground into a fine flour, giving a naturally sweet, molasses-like flavor. The pods have a firm outer shell with a chewy pulp inside that can be dried and milled.

The seeds inside the pods are not eaten raw—they’re too hard to digest and should be discarded or removed during processing. Mesquite flour works well in baking or as a flavor enhancer in drinks and sauces.

Avoid confusing mesquite with acacia species that also bear seed pods but often have toxic or bitter seeds; mesquite pods are typically more curved and lack the intense tannins. Taste is the easiest way to confirm—mesquite is sweet, not astringent.

The tree’s bark and leaves aren’t used in cooking, so focus only on harvesting the pods. Even when dried, the flour has excellent shelf life, making it a favorite among desert foragers.

Miner’s lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata)

Miner’s lettuce, also known as Indian lettuce and winter purslane, has round, cup-shaped leaves that almost look like they are threaded through the stem. Tiny white flowers often bloom right in the center of the leaf, giving it a distinctive, easy-to-spot look if you are paying attention.

The leaves and stems are edible and have a crisp, tender texture with a mild, slightly sweet flavor. Some people describe the taste as a little like spinach but even fresher and lighter when eaten raw.

You can toss miner’s lettuce straight into salads, blend it into smoothies, or lightly sauté it for a simple side dish. It also holds up well when added to sandwiches or wrapped in tortillas if you want a bit of fresh crunch.

While it is generally safe to eat, it is important to avoid confusing miner’s lettuce with toxic lookalikes like young spurge plants, which have a milky sap if snapped. Always double-check that the stems are smooth and the flowers are small and white before harvesting anything to eat.

Prickly Pear (Opuntia spp.)

Prickly pear cactus has flat, paddle-shaped pads with spines all over them. They grow bright flowers that turn into juicy, egg-shaped fruits. These fruits can be green to purplish-red when ripe. Both the pads and fruits can be eaten if prepared right.

You must remove all the spines and tiny hair-like prickles before eating any part. These tiny prickles, called glochids, can really hurt your skin. The fruits taste sweet like watermelon, while the pads taste like green beans when cooked.

Always use thick gloves or tongs when picking prickly pear. The pads have lots of vitamins and fiber. The fruits have strong antioxidants and have been used to help control blood sugar. No other plants look like prickly pear, but you must be careful handling it to avoid getting poked.

Pinyon pine (Pinus monophylla)

The pinyon pine, sometimes called single-leaf pinyon, is easy to spot because it has just one needle per bundle instead of the usual two or more. The tree stays small and bushy, with a rounded shape and dense clusters of short, bluish-green needles.

The pine nut hidden inside the thick-shelled cones is the only edible part of the tree, and it has a rich, buttery flavor when eaten raw or roasted. The seeds are small compared to commercial pine nuts but have a soft, slightly chewy texture that makes them easy to enjoy by the handful.

You can crack open the shells and eat the seeds fresh, toast them lightly to bring out a deeper flavor, or grind them into sauces or spreads. Only the seeds are edible, so avoid nibbling on the cones, bark, or needles, which are not considered safe to eat.

Make sure not confuse the pinyon pine with other types of pines that either do not produce edible seeds or have seeds too small to bother collecting. Single-leaf pinyon cones are larger and rounder than many other pines, and the tree’s distinctive needle pattern helps make a positive ID.

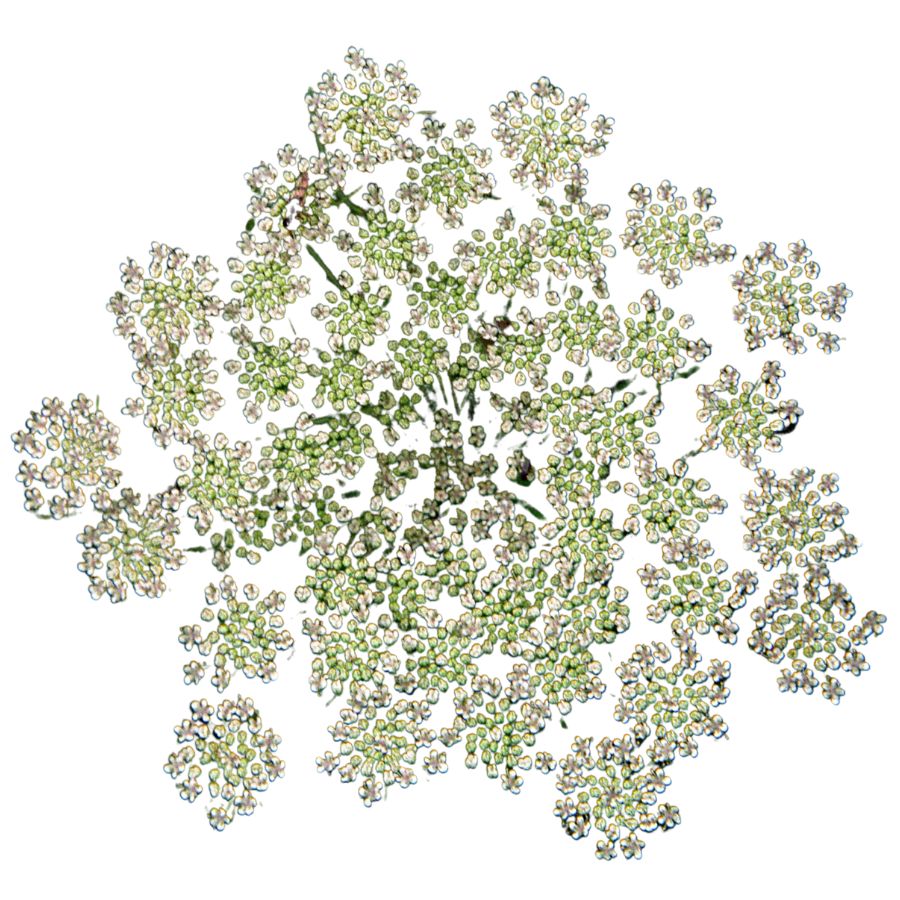

Plantain (Plantago spp.)

Plantain, also called common plantain or narrowleaf plantain depending on the type, is a low-growing plant with broad or lance-shaped leaves and tall, slender flower spikes. The leaves grow in a rosette close to the ground, and the thick veins running through them are one of the easiest ways to tell it apart from other plants.

You can mainly eat the young leaves and the seeds of the plants. Older leaves can become tough and stringy, so it is best to pick the smaller, tender ones when you want to eat them.

Plantain leaves have a slightly bitter, earthy taste and a chewy texture, especially when eaten raw. Many people like to add them to salads, soups, or stews, or lightly steam them to soften the flavor.

Always make sure you have a true plantain before eating because some similar-looking yard plants are not palatable and can upset your stomach. Look for the strong parallel veins and the tough, fibrous stems to help confirm your find.

Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica)

Stinging nettle is also known as burn weed or devil leaf, and it definitely earns those names. The tiny hairs on its leaves and stems can leave a painful, tingling rash if you brush against it raw, so always wear gloves when handling it.

Once it’s cooked or dried, those stingers lose their punch, and the leaves turn mild and slightly earthy in flavor. The texture softens too, making it a solid substitute for spinach in soups, pastas, or even as a simple sauté.

The young leaves and tender tops are what you want to collect. Avoid the tough lower stems and older leaves, which can be gritty or unpleasant to chew.

Some people confuse stinging nettle with purple deadnettle or henbit, but those don’t sting and have more rounded, fuzzy leaves. If the plant doesn’t make your skin react, it’s not stinging nettle.

Thistle (Cirsium spp.)

Thistles have spiny leaves that grow in a circle pattern close to the ground. Later, they send up tall stalks with purple flower heads. Though they look very prickly, several parts of thistles can be eaten if you prepare them properly. Thistles grow in many places where soil has been dug up.

You can eat the roots, young leaves, and flower stems after removing the spines. Young leaves taste like spinach when cooked. The inside of the flower stem, once peeled, is crisp and tastes a bit like cucumber.

You can easily spot thistles by their spiny leaves and purple flowers. Always wear thick gloves when picking them. No poisonous plants look much like thistles.

The peeled stems have vitamin C, and the roots can be cooked like vegetables. Some thistle species also make edible seeds you can collect from the dried flower heads.

Yucca (Yucca spp.)

With its spiny, bluish-green leaves and tall central stalk, yucca grows in dry, rocky soils and can be surprisingly versatile as a food plant. The petals of the flower can be eaten raw but are usually cooked to tame their bitter edge and soften the waxy texture.

Avoid confusing it with Spanish dagger, which is a close relative but has leaf margins sharp enough to cut skin and isn’t as commonly consumed. Only certain species of yucca have edible roots, so be sure you know what you’re digging up.

Its roots need thorough cooking to be safe and digestible—usually sliced thin and roasted or simmered until soft. Once cooked, they taste mildly sweet and nutty, with a starchiness like parsnips.

Yucca flowers are sometimes dipped in batter and fried, giving them a crisp shell and tender inside. You shouldn’t try to eat the seed pods or mature leaves, which can carry irritating compounds even in small doses.

Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

There are plenty of wild edibles to choose from, but some toxic native plants closely resemble them. Mistaking the wrong one can lead to severe illness or even death, so it’s important to know exactly what you’re picking.

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild carrot (Daucus carota)

Poison hemlock is a tall plant with lacy leaves and umbrella-like clusters of tiny white flowers. It has smooth, hollow stems with purple blotches and grows in sunny places like roadsides, meadows, and stream banks.

Unlike wild carrot, which has hairy stems and a dark central floret, poison hemlock has a musty odor and no flower center spot. It’s extremely toxic; just a small amount can be fatal, and even touching the sap can irritate the skin.

Water Hemlock (Cicuta spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) or wild celery (Apium spp.)

Water hemlock is a tall, branching plant with umbrella-shaped clusters of small white flowers. It grows in wet places like stream banks, marshes, and ditches, with stems that often show purple streaks or spots.

It can be confused with wild parsnip or wild celery, but its thick, hollow roots have internal chambers and release a yellow, foul-smelling sap when cut. Water hemlock is the most toxic plant in North America, and just a small amount can cause seizures, respiratory failure, and death.

False Hellebore (Veratrum viride)

Often mistaken for: Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

False hellebore is a tall plant with broad, pleated green leaves that grow in a spiral from the base, often appearing early in spring. It grows in moist woods, meadows, and along streams.

It’s commonly mistaken for ramps, but ramps have a strong onion or garlic smell, while false hellebore is odorless and later grows a tall flower stalk. The plant is highly toxic, and eating any part can cause nausea, a slowed heart rate, and even death due to its alkaloids that affect the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Death Camas (Zigadenus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild onion or wild garlic (Allium spp.)

Death camas is a slender, grass-like plant that grows from underground bulbs and is found in open woods, meadows, and grassy hillsides. It has small, cream-colored flowers in loose clusters atop a tall stalk.

It’s often confused with wild onion or wild garlic due to their similar narrow leaves and habitats, but only Allium plants have a strong onion or garlic scent, while death camas has none. The plant is extremely poisonous, especially the bulbs, and even a small amount can cause nausea, vomiting, a slowed heartbeat, and potentially fatal respiratory failure.

Buckthorn Berries (Rhamnus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Elderberries (Sambucus spp.)

Buckthorn is a shrub or small tree often found along woodland edges, roadsides, and disturbed areas. It produces small, round berries that ripen to dark purple or black and usually grow in loose clusters.

These berries are sometimes mistaken for elderberries and other wild fruits, which also grow in dark clusters, but elderberries form flat-topped clusters on reddish stems while buckthorn berries are more scattered. Buckthorn berries are unsafe to eat as they contain compounds that can cause cramping, vomiting, and diarrhea, and large amounts may lead to dehydration and serious digestive problems.

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Mayapple is a low-growing plant found in shady forests and woodland clearings. It has large, umbrella-like leaves and produces a single pale fruit hidden beneath the foliage.

The unripe fruit resembles a small green grape, causing confusion with wild grapes, which grow in woody clusters on vines. All parts of the mayapple are toxic except the fully ripe, yellow fruit, which is only safe in small amounts. Eating unripe fruit or other parts can lead to nausea, vomiting, and severe dehydration.

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Virginia creeper is a fast-growing vine found on fences, trees, and forest edges. It has five leaflets per stem and produces small, bluish-purple berries from late summer to fall.

It’s often confused with wild grapes since both are climbing vines with similar berries, but grapevines have large, lobed single leaves and tighter fruit clusters. Virginia creeper’s berries are toxic to humans and contain oxalate crystals that can cause nausea, vomiting, and throat irritation.

Castor Bean (Ricinus communis)

Often mistaken for: Wild rhubarb (Rumex spp. or Rheum spp.)

Castor bean is a bold plant with large, lobed leaves and tall red or green stalks, often found in gardens, along roadsides, and in disturbed areas in warmer regions in the US. Its red-tinged stems and overall size can resemble wild rhubarb to the untrained eye.

Unlike rhubarb, castor bean plants produce spiny seed pods containing glossy, mottled seeds that are extremely toxic. These seeds contain ricin, a deadly compound even in small amounts. While all parts of the plant are toxic, the seeds are especially dangerous and should never be handled or ingested.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

How to Get the Best Results Foraging

Safety should always come first when it comes to foraging. Whether you’re in a rural forest or a suburban greenbelt, knowing how to harvest wild foods properly is a key part of staying safe and respectful in the field.

Always Confirm Plant ID Before You Harvest Anything

Knowing exactly what you’re picking is the most important part of safe foraging. Some edible plants have nearly identical toxic lookalikes, and a wrong guess can make you seriously sick.

Use more than one reliable source to confirm your ID, like field guides, apps, and trusted websites. Pay close attention to small details. Things like leaf shape, stem texture, and how the flowers or fruits are arranged all matter.

Not All Edible Plants Are Safe to Eat Whole

Just because a plant is edible doesn’t mean every part of it is safe. Some plants have leaves, stems, or seeds that can be toxic if eaten raw or prepared the wrong way.

For example, pokeweed is only safe when young and properly cooked, while elderberries need to be heated before eating. Rhubarb stems are fine, but the leaves are poisonous. Always look up which parts are edible and how they should be handled.

Avoid Foraging in Polluted or Contaminated Areas

Where you forage matters just as much as what you pick. Plants growing near roads, buildings, or farmland might be coated in chemicals or growing in polluted soil.

Even safe plants can take in harmful substances from the air, water, or ground. Stick to clean, natural areas like forests, local parks that allow foraging, or your own yard when possible.

Don’t Harvest More Than What You Need

When you forage, take only what you plan to use. Overharvesting can hurt local plant populations and reduce future growth in that area.

Leaving plenty behind helps plants reproduce and supports wildlife that depends on them. It also ensures other foragers have a chance to enjoy the same resources.

Protect Yourself and Your Finds with Proper Foraging Gear

Having the right tools makes foraging easier and safer. Gloves protect your hands from irritants like stinging nettle, and a good knife or scissors lets you harvest cleanly without damaging the plant.

Use a basket or breathable bag to carry what you collect. Plastic bags hold too much moisture and can cause your greens to spoil before you get home.

This forager’s toolkit covers the essentials for any level of experience.

Watch for Allergic Reactions When Trying New Wild Foods

Even if a wild plant is safe to eat, your body might react to it in unexpected ways. It’s best to try a small amount first and wait to see how you feel.

Be extra careful with kids or anyone who has allergies. A plant that’s harmless for one person could cause a reaction in someone else.

Check Local Rules Before Foraging on Any Land

Before you start foraging, make sure you know the rules for the area you’re in. What’s allowed in one spot might be completely off-limits just a few miles away.

Some public lands permit limited foraging, while others, like national parks, usually don’t allow it at all. If you’re on private property, always get permission first.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

Where to Find Forageables in the State

There is a range of foraging spots where edible plants grow naturally and often in abundance:

| Plant | Locations |

|---|---|

| Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) | – Washoe Lake State Park – River Fork Ranch Preserve – Peavine Peak foothills |

| Beeplant (Cleome serrulata) | – South Fork State Recreation Area – Smith Valley Grasslands – Mason Valley Wildlife Area |

| Biscuitroot (Lomatium spp.) | – Spring Mountains National Recreation Area – Ruby Lake National Wildlife Refuge – Desatoya Mountains |

| Bitterroot (Lewisia rediviva) | – Highland Ridge Wilderness – Kingston Canyon – Ward Mountain Recreation Area |

| Cattail (Typha spp.) | – Washoe Lake State Park – Carson River Park – Mason Valley Wildlife Management Area |

| Checkermallow (Sidalcea spp.) | – Genoa Trail System – Elko Hills Natural Area – Dayton State Park |

| Chia (Salvia columbariae) | – Cathedral Gorge State Park – Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge – Kershaw-Ryan State Park |

| Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) | – Lamoille Canyon – Ruby Mountains Wilderness – Jarbidge Wilderness |

| Creeping hollygrape (Mahonia repens) | – Galena Creek Recreation Area – Mount Rose Wilderness – Spooner Lake Backcountry |

| Currant (Ribes spp.) | – Walker River State Recreation Area – South Fork State Recreation Area – Ward Charcoal Ovens State Historic Park |

| Elder (Sambucus spp.) | – Fort Churchill State Historic Park – River Fork Ranch Preserve – Carson River Park |

| Evening primrose (Oenothera spp.) | – Tule Springs Fossil Beds – Red Rock Canyon NCA – Corn Creek Desert Park |

| Field pennycress (Thlaspi arvense) | – Washoe Lake State Park – Fort Churchill State Historic Park – Lahontan State Recreation Area |

| Gooseberry (Ribes spp.) | – Lamoille Canyon – Mount Charleston Recreation Area – Cave Lake State Park |

| Ground cherry (Physalis spp.) | – Sand Mountain Recreation Area – Pahranagat National Wildlife Refuge – Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge |

| Hollygrape (Mahonia fremontii) | – Spring Mountains NRA – Cathedral Gorge State Park – Kershaw-Ryan State Park |

| Indian ricegrass (Achnatherum hymenoides) | – Red Rock Canyon NCA – Sand Hollow Wash Trail – Amargosa Valley Trails |

| Lambsquarters (Chenopodium album) | – Mason Valley WMA – Washoe Lake State Park – Fort Churchill State Historic Park |

| Lemonade berry (Rhus integrifolia) | – Red Rock Canyon NCA – Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve – Lake Mead NRA |

| Manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.) | – Spooner Lake Backcountry – Galena Creek Recreation Area – Mount Rose Wilderness |

| Maple (Acer spp.) | – Kyle Canyon Trail – Deer Creek Picnic Area – Mary Jane Falls Trail |

| Mariposa lily (Calochortus spp.) | – Ruby Mountains Wilderness – Jarbidge Wilderness – Spring Mountains NRA |

| Mesquite (Prosopis spp.) | – Valley of Fire State Park – Moapa Valley NWR – Overton Wildlife Management Area |

| Miner’s lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata) | – Galena Creek Trail – Mount Rose Wilderness – Tahoe Meadows Interpretive Loop |

| Monkey flower (Mimulus spp.) | – Lamoille Canyon – Ruby Mountains – Verdi Peak Trail |

| Mullein (Verbascum thapsus) | – Ward Mountain Recreation Area – Fort Churchill SHP – South Fork SRA |

| Nettle (Urtica dioica) | – Genoa Trail System – Spooner Lake – Verdi Nature Trail |

| Oak (Quercus spp.) | – Mount Charleston Wilderness – Ruby Mountains – Cave Lake State Park |

| Orach (Atriplex spp.) | – Lahontan State Recreation Area – Fort Churchill SHP – Mason Valley WMA |

| Panicgrass (Panicum spp.) | – River Fork Ranch Preserve – Carson River Park – Washoe Lake State Park |

| Pellitory (Parietaria spp.) | – Genoa Park Trail – Sparks Marina Park – Deer Run Nature Trail |

| Pinyon pine (Pinus monophylla) | – Highland Ridge Wilderness – Schell Creek Range – Spring Mountains NRA |

| Plantain (Plantago spp.) | – South Fork State Recreation Area – Washoe Lake State Park – Walker River SRA |

| Prickly pear (Opuntia spp.) | – Red Rock Canyon NCA – Valley of Fire State Park – Desert National Wildlife Refuge |

| Raspberry (Rubus spp.) | – Ruby Mountains Wilderness – Jarbidge Wilderness – Mount Rose Wilderness |

| Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia) | – Carson River Park – Mason Valley WMA – Smith Valley Reserve |

| Salsify (Tragopogon spp.) | – Sparks Marina Park – Washoe Lake State Park – Dayton State Park |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia) | – Lamoille Canyon – Galena Creek – Mount Rose Wilderness |

| Smartweed (Polygonum spp.) | – Fort Churchill SHP – River Fork Ranch Preserve – South Fork SRA |

| Springparsley (Cymopterus spp.) | – Ruby Mountains – Desatoya Mountains – Spring Mountains NRA |

| Squaw apple (Peraphyllum ramosissimum) | – Mount Charleston – Galena Creek – Ruby Mountains |

| Thistle (Cirsium spp.) | – Fort Churchill SHP – River Fork Ranch Preserve – Lahontan SRA |

| Tuber starwort (Pseudostellaria jamesiana) | – Spring Creek Trail – Verdi Peak Forest – Mount Rose Meadow |

| Tule (Schoenoplectus spp.) | – Mason Valley WMA – Washoe Lake marshlands – Carson River Preserve |

| Tumble mustard (Sisymbrium altissimum) | – South Fork SRA – Smith Valley roadsides – Dayton State Park |

| Tumbleweed (Salsola spp.) | – Sparks Dunes Trail – Ely Bypass Open Space – Yerington Wildland Fringe |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | – Genoa Trail Streams – Verdi Wetlands – South Fork SRA |

| Western spring beauty (Claytonia lanceolata) | – Ruby Mountains Wilderness – Lamoille Canyon – Tahoe Meadows |

| Wild gourd (Cucurbita foetidissima) | – Valley of Fire State Park – Ash Meadows NWR – Amargosa Valley |

| Wild onion (Allium spp.) | – Lamoille Canyon – Mount Charleston – Ruby Mountains |

| Wild rose (Rosa spp.) | – Galena Creek – Walker River SRA – South Fork SRA |

| Wild sunflower (Helianthus spp.) | – Sparks Marina Park – Carson River Park – Mason Valley WMA |

| Wintercress (Barbarea spp.) | – Genoa Park Trail – Galena Creek – Dayton State Park |

| Wolfberry (Lycium spp.) | – Red Rock Canyon NCA – Valley of Fire State Park – Amargosa Basin |

| Yampah (Perideridia spp.) | – Ruby Mountains – Lamoille Canyon – Spring Mountains NRA |

| Yellowdock (Rumex crispus) | – Carson River Park – Fort Churchill SHP – Mason Valley WMA |

| Yucca (Yucca baccata) | – Valley of Fire State Park – Red Rock Canyon NCA – Cathedral Gorge State Park |

Peak Foraging Seasons

Different edible plants grow at different times of year, depending on the season and weather. Timing your search makes all the difference.

Spring

Spring brings a fresh wave of wild edible plants as the ground thaws and new growth begins:

| Plant | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Beeplant (Cleome serrulata) | May–June | sunny open slopes and roadsides |

| Checkermallow (Sidalcea spp.) | April–June | moist hillsides |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | March–April | moist shady spots |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | March–May | sunny meadows after light rain |

| Field pennycress (Thlaspi arvense) | April–May | cool farm edges or garden borders |

| Lambsquarters (Chenopodium album) | April–June | disturbed soil in sunny areas |

| Miner’s lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata) | March–May | cool, damp forest floor |

| Orach (Atriplex spp.) | April–June | salty or disturbed soils in open fields |

| Pellitory (Parietaria spp.) | April–June | shaded wall bases and woodland edges |

| Smartweed (Polygonum spp.) | April–June | wet, disturbed areas near streams |

| Western spring beauty (Claytonia lanceolata) | March–May | shady alpine glades |

| Wild onion (Allium spp.) | March–May | grassy meadows and sandy soils |

| Yampah (Perideridia spp.) | April–May | open mountain meadows |

Summer

Summer is a peak season for foraging, with fruits, flowers, and greens growing in full force:

| Plant | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Chia (Salvia columbariae) | June–July | arid low-elevation desert trails |

| Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) | July–August | moist mountain valleys |

| Currant (Ribes spp.) | July–August | riparian woodlands |

| Evening primrose (Oenothera spp.) | June–August | dry open fields and roadside patches |

| Gooseberry (Ribes spp.) | June–July | shaded slopes and canyons |

| Ground cherry (Physalis spp.) | July–August | dry, sandy flats and disturbed soils |

| Manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.) | June–July | dry slopes with chaparral scrub |

| Maple (Acer spp.) | June–July | moist canyons or shaded mountain slopes |

| Monkey flower (Mimulus spp.) | June–August | wet meadows and stream edges |

| Purslane (Portulaca oleracea) | June–September | warm, compacted soil near gardens or paths |

| Raspberry (Rubus spp.) | June–August | moist forest margins and clearings |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia) | June–August | sunny hillsides and forest edges |

| Thistle (Cirsium spp.) | June–August | disturbed ground and open meadows |

| Wild rose (Rosa spp.) | June–August | edges of moist meadows or forest openings |

Fall

As temperatures drop, many edible plants shift underground or produce their last harvests:

| Plant | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Acorn (Quercus spp.) | September–November | oak groves in valleys and hillsides |

| Hollygrape (Mahonia fremontii) | September–October | dry slopes with sparse tree cover |

| Indian ricegrass (Achnatherum hymenoides) | September–October | sandy desert flats |

| Mesquite (Prosopis spp.) | August–September | arid basin bottoms and river washes |

| Pinyon pine (Pinus monophylla) | September–October | dry slopes and ridgelines |

| Prickly pear (Opuntia spp.) | August–October | sunny deserts and dry hillsides |

| Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia) | September–October | stream corridors and irrigation ditches |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia) | September–October | dry upland hillsides |

| Squaw apple (Peraphyllum ramosissimum) | September–October | dry slopes and woodland edges |

| Tumble mustard (Sisymbrium altissimum) | September–October | disturbed roadside areas |

| Wild rose hips (Rosa spp.) | September–November | edges of meadows and forests |

| Wild sunflower (Helianthus spp.) | September–October | open dry fields |

| Yucca (Yucca baccata) | August–October | desert foothills and slopes |

Winter

Winter foraging is limited but still possible, with hardy plants and preserved growth holding on through the cold:

| Plant | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) | November–January | harvest dried seeds in late season |

| Beeplant (Cleome serrulata) | November | dry stemmed areas on hillsides (for seed pods) |

| Cattail (Typha spp.) | November–February | frozen marsh edges and pond margins |

| Dock (Rumex crispus) | November–January | moist lowland areas |

| Mullein (Verbascum thapsus) | November–January | dry, open roadsides and slopes |

| Pine nuts (Pinus monophylla) | December–January | pinyon groves at mid elevations |

| Tuber starwort (Pseudostellaria jamesiana) | December–February | shady pine woodlands |

| Tule (Schoenoplectus spp.) | December–February | marsh margins and shallow wetlands |

| Tumbleweed (Salsola spp.) | November–January | arid vacant lots and sandy fields |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | November–February | clean, flowing streams |

| Wild onion (Allium spp.) | December–February | grassy meadows and sandy soils |

| Wintercress (Barbarea spp.) | November–January | cool, moist woodlands |

| Wolfberry (Lycium spp.) | December–February | desert shrublands |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.