Nebraska has many tasty plants growing wild across its prairies, forests, and riverbanks. These natural foods have fed people for thousands of years. You can learn to find them too.

Walking through Nebraska landscapes becomes more exciting when you know what plants you can eat. The land offers different edible options in each season.

Spring brings tender greens like dandelions and wild onions poking through the soil. Summer fills the state with juicy berries and edible flowers. Fall offers nuts and seeds as trees prepare for winter.

Learning to identify wild plants safely is the first step to becoming a good forager. Not all wild plants are safe to eat. Some look very similar to dangerous ones.

Local knowledge passed down through generations helps us find these natural foods. Native American tribes in Nebraska knew exactly when and where to gather each plant. Their wisdom still guides modern foragers today.

What We Cover In This Article:

- The Edible Plants Found in the State

- Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

- How to Get the Best Results Foraging

- Where to Find Forageables in the State

- Peak Foraging Seasons

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

The Edible Plants Found in the State

Wild plants found across the state can add fresh, seasonal ingredients to your meals:

Amaranth (Amaranthus retroflexus)

Amaranth grows as a tall, sturdy plant with reddish stems and large, oval leaves that have a slight notch at the tip. The plant produces thousands of tiny black seeds in dense, upright flower clusters that often have a reddish-purple hue.

Every part of amaranth offers something for foragers. The young leaves make excellent greens in salads or can be cooked like spinach. The seeds can be harvested and cooked as a grain.

When identifying amaranth, look for the distinctive flower spikes and the reddish stems. No dangerous lookalikes exist, but some amaranth species have higher levels of oxalic acid.

Amaranth has been eaten for thousands of years by cultures worldwide. It contains more protein than most plants and offers calcium, iron, and lysine, an amino acid rarely found in plant foods.

American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)

Persimmon, sometimes called American persimmon or common persimmon, grows as a small tree with rough, blocky bark and oval-shaped leaves. The fruit looks like a small, flattened tomato and turns a deep orange or reddish color when ripe.

If you bite into an unripe persimmon, you will quickly notice an extremely astringent, mouth-drying effect. A ripe persimmon, on the other hand, tastes sweet, rich, and custard-like, with a soft and jelly-like texture inside.

You can eat persimmons fresh once they are fully ripe, or you can cook them down into puddings, jams, and baked goods. Some people also mash and freeze the pulp to use later for pies, breads, and sauces.

Wild persimmons can sometimes be confused with black nightshade berries, but nightshade fruits are much smaller, grow in clusters, and stay dark purple or black. Only the ripe fruit of the persimmon tree should be eaten; the seeds and the unripe fruit are not edible.

Burdock (Arctium minus)

Burdock, also known as burrweed or beggar’s buttons, grows large, floppy leaves and produces clusters of sticky seed heads that cling to clothing and fur. The plant can easily tower over you once it matures, especially when the thick stalks shoot up.

The root is the main edible part and has a crisp texture with a mild, sweet, slightly earthy flavor when cooked. You should avoid eating the leaves or seed heads, as they tend to be unpleasantly bitter and tough even when young.

When you cook burdock root, it works well sliced thin and stir-fried, boiled into soups, or simmered with other vegetables to soak up savory flavors. Peeling the root before cooking can help soften the flavor and improve the texture.

It is important to watch out for lookalikes like foxglove and woolly mullein, which can grow similarly large leaves at the base. True burdock leaves have a whitish, fuzzy underside and strong, fibrous stems that are solid rather than hollow.

Cattail (Typha spp.)

The distinctive brown, cigar-shaped seed heads of cattails make them one of the easiest plants to spot in wetland areas. Growing in shallow water, these plants have long, flat leaves that wrap around the stem at the base.

Cattails are often called the “supermarket of the swamp” because nearly every part is edible at some point in the year. The young shoots and stalks can be eaten raw or cooked, while the pollen makes a nutritious flour.

To harvest cattails, pull young shoots from the center of the plant in spring. The pollen can be collected by bending the flower head into a bag and shaking gently.

No poisonous lookalikes exist, though iris plants can grow in similar areas and are toxic. Cattails can be identified by their brown seed heads and their growth pattern in standing water.

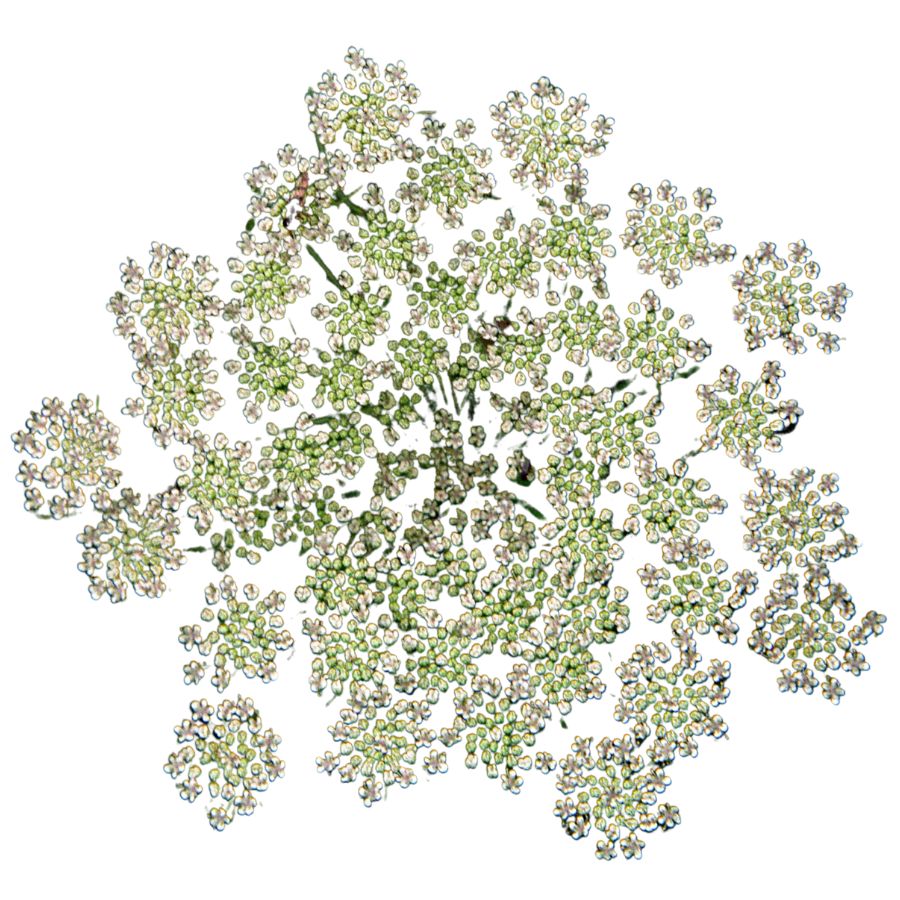

Chickweed (Stellaria media)

Chickweed, sometimes called satin flower or starweed, is a small, low-growing plant with delicate white star-shaped flowers and bright green leaves. The leaves are oval, pointed at the tip, and often grow in pairs along a slender, somewhat weak-looking stem.

When gathering chickweed, watch out for lookalikes like scarlet pimpernel, which has similar leaves but orange flowers instead of white. A key detail to check is the fine line of hairs that runs along one side of chickweed’s stem, a feature the dangerous lookalikes do not have.

The young leaves, tender stems, and flowers of chickweed are all edible, offering a mild, slightly grassy flavor with a crisp texture. You can toss it fresh into salads, blend it into pestos, or lightly wilt it into soups and stir-fries for a fresh green boost.

Aside from being a food plant, chickweed has been used traditionally in poultices and salves to help soothe skin irritations. Always make sure the plant is positively identified before eating, since mistaking it for a toxic lookalike could cause serious issues.

Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana)

Clusters of dark berries hanging from a woody shrub usually indicate chokecherries, especially when the leaves are oval with finely toothed edges. These berries turn from red to deep purple or black when they’re ready to eat.

Chokecherries are rarely eaten raw due to their bitterness, but they shine in cooked recipes like preserves, sauces, or even homemade wine. Boiling the fruit and straining it helps separate the pulp from the inedible seeds.

It’s easy to mix up chokecherries with other wild cherries, but true chokecherries have longer, narrower leaves and a more astringent taste. Avoid anything with rounder, solitary berries or a sweet scent without the signature tartness.

Their texture is slightly gritty around the pit, and the flavor improves significantly with sugar and heat. A strong astringent quality dominates the raw berry, but the processed pulp becomes rich and deeply flavored.

Common Mallow (Malva neglecta)

Often dismissed as a weed in gardens and lawns, common mallow has rounded leaves with scalloped edges and a circular growth pattern close to the ground. Small, five-petaled pale pink or white flowers bloom throughout the growing season.

The leaves and immature seed pods of mallow are both edible. When chewed, the leaves release a mucilage that gives them a slightly slimy texture, similar to okra.

Common mallow contains vitamins A and C, along with calcium and potassium. The mucilage in mallow leaves soothes irritated digestive tracts, making it valuable for both food and medicine.

When foraging for mallow, ensure you’re not collecting from areas treated with herbicides or pesticides. There are no toxic lookalikes, but always confirm identification by checking for the cheese-wheel shaped seed pods that give it the nickname “cheeseweed.”

Currant (Ribes spp.)

Currants are small, shrubby plants that produce clusters of round berries and are often called wild currants or gooseberries, depending on the species. You can recognize them by their lobed leaves, slender stems, and berries that come in shades of red, black, or even golden yellow.

Some currant plants have lookalikes, such as certain types of nightshade, which can be toxic if eaten. To tell them apart, check the leaves and stems closely because real currants have woody stems and leaves that feel soft and slightly rough.

The berries are edible and offer a tart, slightly sweet flavor with a juicy texture that pops when you bite into them. People often use currants to make jams, jellies, syrups, and even baked goods like tarts and cakes.

While currant berries are a treat, the leaves can also be used to flavor teas, although they are not as widely eaten.

It’s important to avoid eating any berries that taste bitter or look unfamiliar, since not all wild berries are safe.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

Bright yellow flowers and jagged, deeply toothed leaves make dandelions easy to spot in open fields, lawns, and roadsides. You might also hear them called lion’s tooth, blowball, or puffball once the flowers turn into round, white seed heads.

Every part of the dandelion is edible, but you will want to avoid harvesting from places treated with pesticides or roadside areas with heavy car traffic. Besides being a food source, dandelions have been used traditionally for simple herbal remedies and natural dye projects.

Young dandelion leaves have a slightly bitter, peppery flavor that works well in salads or sautés, and the flowers can be fried into fritters or brewed into tea. Some people even roast the roots to make a coffee substitute with a rich, earthy taste.

One thing to watch out for is cat’s ear, a common lookalike with hairy leaves and branching flower stems instead of a single, hollow one. To make sure you have a true dandelion, check for a smooth, hairless stem that oozes a milky sap when broken.

Gooseberry (Ribes missouriense)

These small, translucent green berries hang from shrubs with maple-like leaves and small thorns along the stems. When ripe, gooseberries develop a sweet-tart flavor that makes them perfect for jams and pies.

To identify gooseberries, look for the thorny stems and lobed leaves. The berries themselves have distinctive vertical stripes and often retain a small dried flower at the end opposite the stem.

The entire berry is edible, though some foragers remove the small stem and flower end before eating. They can be eaten raw when fully ripe or cooked when still firm.

No dangerous lookalikes exist for gooseberries. However, unripe berries are quite sour and may cause stomach upset if eaten in large quantities. Gooseberries provide vitamin C and fiber, making them both tasty and nutritious wild treats.

Ground Cherry (Physalis longifolia)

Ground cherries grow as low, bushy plants with small yellow-orange fruits wrapped in papery husks. The fruits resemble tiny lanterns hanging from the plant, giving them their nickname “lantern fruit.” When ripe, they fall to the ground and develop a sweet, tropical flavor with hints of pineapple and vanilla.

These fruits are ready to eat when the husks turn tan and the fruit drops from the plant. Only eat the berries, as the leaves, stems, and unripe fruits contain solanine, which can be toxic.

The papery husk helps identify ground cherries and distinguishes them from potentially toxic nightshade relatives. Simply peel back the husk and enjoy the fruit raw, or use it in jams, pies, and salsas.

Ground cherries are packed with vitamins A and C, making them nutritious foraged finds. They also contain beneficial antioxidants that support eye health and boost immunity.

Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

The small, pea-sized fruits of the hackberry tree contain a sweet, date-like pulp surrounding a large seed. These trees can be identified by their distinctive warty, gray bark and asymmetrical leaves with serrated edges.

Hackberries remain on the tree into winter, often becoming sweeter after frost. The fruits can be eaten raw, with a flavor reminiscent of dates with hints of brown sugar.

The hard seed inside should not be eaten, but the thin skin and sweet flesh are perfectly edible. Some foragers dry and grind the berries with the seeds to make a nutritious flour.

Unlike some wild berries, hackberries have no poisonous lookalikes, making them a safe choice for beginning foragers. These fruits are rich in carbohydrates and provide a quick energy boost during winter foraging trips when other food sources are scarce.

Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

Wild bergamot has clusters of lavender-colored flowers and opposite leaves that smell like thyme when crushed. Its flavor leans herbal and minty, with a little bitterness that works well in marinades.

The flower heads are shaggy and irregular, and the plant’s square stem helps tell it apart from lookalikes like spotted horsemint.

In recipes, it’s most often dried and steeped or blended into herb mixes.

Both leaves and petals can be eaten, though most people avoid the stems. Don’t eat it in large amounts raw—it’s strong and can be overpowering.

It’s related to mint, and that shows in how fast the flavor develops when heat is applied. You’ll get the most aroma if you bruise the leaves before using them.

Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus)

Jerusalem artichoke grows tall with sunflower-like blooms and has knobby underground tubers. The tubers are tan or reddish and look a bit like ginger root, though they belong to the sunflower family.

The part you’re after is the tuber, which has a nutty, slightly sweet flavor and a crisp texture when raw. You can roast, sauté, boil, or mash them like potatoes, and they hold their shape well in soups and stir-fries.

Some people experience gas or bloating after eating sunchokes due to the inulin they contain, so it’s a good idea to try a small amount first. Cooking them thoroughly can help reduce the chances of digestive discomfort.

Sunchokes don’t have many dangerous lookalikes, but it’s important not to confuse the plant with other sunflower relatives that don’t produce tubers. The above-ground part resembles a small sunflower, but it’s the knotted, underground tubers that are worth digging up.

Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

Known for its thick stems, broad leaves, and clusters of pinkish-purple flowers, common milkweed is sometimes called silkweed or butterfly flower. When you snap a stem or leaf, it releases a milky sap that helps you tell it apart from other plants that can be harmful.

If you want to try it in the kitchen, focus on gathering the young shoots, the tightly closed flower buds, and the small, immature pods. These parts have a mild, slightly sweet flavor when cooked, and their soft texture makes them a good addition to soups, sautés, and fritters.

Getting it ready to eat takes a little care, since boiling the plant parts in several changes of water helps remove bitterness and unwanted compounds. Some people also like to steam the buds or fry the pods lightly to bring out their best taste.

Although monarch caterpillars rely on this plant for survival, it has a long history of being used by people as well. Watch out for lookalikes like dogbane, though, since they share the same milky sap but are dangerously toxic if eaten.

Mulberry (Morus rubra)

Mulberries hang from deciduous trees that can reach up to 65 feet tall in eastern North America. The berries start green, then ripen to deep purple or black and resemble elongated blackberries. Their sweet, juicy flavor has made them a traditional wild food source for generations.

The entire berry is edible and requires no special preparation. Wild mulberries contain high levels of antioxidants, vitamin C, and iron.

To identify mulberry trees, look for heart-shaped leaves with serrated edges and distinctive ridged bark. Unlike some toxic berries, mulberries grow directly on stems without additional husks or structures.

Mulberry juice stains clothing and hands easily, so wear dark clothing when harvesting. The berries can be eaten fresh, dried like raisins, or made into jams, wines, and desserts. Birds often compete for these nutritious fruits, so timing your harvest is important.

Nettle (Urtica dioica)

Stinging nettle is also known as burn weed or devil leaf, and it definitely earns those names. The tiny hairs on its leaves and stems can leave a painful, tingling rash if you brush against it raw, so always wear gloves when handling it.

Once it’s cooked or dried, those stingers lose their punch, and the leaves turn mild and slightly earthy in flavor. The texture softens too, making it a solid substitute for spinach in soups, pastas, or even as a simple sauté.

The young leaves and tender tops are what you want to collect. Avoid the tough lower stems and older leaves, which can be gritty or unpleasant to chew.

Some people confuse stinging nettle with purple deadnettle or henbit, but those don’t sting and have more rounded, fuzzy leaves. If the plant doesn’t make your skin react, it’s not stinging nettle.

Plantain (Plantago major)

Plantain is a common lawn “weed” with broad, oval leaves featuring prominent parallel veins that run lengthwise. This humble plant grows in rosette patterns close to the ground and has been used medicinally for centuries to treat wounds, stings, and digestive issues.

Young leaves are tender and can be added raw to salads, while more mature leaves become fibrous and are better cooked like spinach. The entire plant is edible, including the seed stalks, which can be steamed when young.

Plantain contains vitamins A, C, and K, along with beneficial compounds that reduce inflammation. It has no dangerous lookalikes, making it safe for beginner foragers.

To prepare plantain, wash the leaves thoroughly and remove any tough stems. The mild, slightly bitter flavor pairs well with other greens or can be dried for tea. Its widespread availability makes it one of the most accessible wild edibles.

Rose Hips (Rosa spp.)

Rose hips are the fruit that forms after the flower petals fall from wild roses. These bright red to orange fruits resemble tiny apples and contain more vitamin C than oranges, making them valuable winter foraging finds. The tangy, slightly sweet flavor has notes of apple and cranberry.

To identify rose hips, look for shrubs with thorny stems and the distinctive remnant of the flower calyx at the end of each hip. All rose hips are edible, though some varieties are tastier than others.

The outer flesh is the edible part, while the seeds and fine hairs inside should be removed as they can irritate the digestive tract. Cut the hips in half and scoop out the center before using.

Rose hips can be made into teas, jams, syrups, and even wine. They’ve been traditionally used to prevent scurvy and boost immunity during winter months. Their high antioxidant content also supports skin health.

Wild Plum (Prunus americana)

Wild plum trees produce small, round fruits that transform from green to yellow, red, or purple when ripe. These native American plums grow in thickets along forest edges and abandoned fields, often reaching heights of 15-20 feet. The fragrant spring blossoms appear before the leaves, making the trees easy to spot early in the growing season.

The skin can be tart while the flesh offers a sweet-sour balance that intensifies after light frosts. Unlike some wild fruits, wild plums have no toxic lookalikes in North America.

Only the fruit flesh is edible, as the pits contain small amounts of cyanide compounds, similar to other stone fruits. The fruit can be eaten fresh or processed into preserves, jellies, and wines.

Wild plums provide important vitamins and minerals, including vitamins A and C. Their natural pectin content makes them excellent for making preserves without adding commercial thickeners. These plums also served as an important food source for Native American tribes throughout history.

Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

There are plenty of wild edibles to choose from, but some toxic native plants closely resemble them. Mistaking the wrong one can lead to severe illness or even death, so it’s important to know exactly what you’re picking.

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild carrot (Daucus carota)

Poison hemlock is a tall plant with lacy leaves and umbrella-like clusters of tiny white flowers. It has smooth, hollow stems with purple blotches and grows in sunny places like roadsides, meadows, and stream banks.

Unlike wild carrot, which has hairy stems and a dark central floret, poison hemlock has a musty odor and no flower center spot. It’s extremely toxic; just a small amount can be fatal, and even touching the sap can irritate the skin.

Water Hemlock (Cicuta spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) or wild celery (Apium spp.)

Water hemlock is a tall, branching plant with umbrella-shaped clusters of small white flowers. It grows in wet places like stream banks, marshes, and ditches, with stems that often show purple streaks or spots.

It can be confused with wild parsnip or wild celery, but its thick, hollow roots have internal chambers and release a yellow, foul-smelling sap when cut. Water hemlock is the most toxic plant in North America, and just a small amount can cause seizures, respiratory failure, and death.

False Hellebore (Veratrum viride)

Often mistaken for: Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

False hellebore is a tall plant with broad, pleated green leaves that grow in a spiral from the base, often appearing early in spring. It grows in moist woods, meadows, and along streams.

It’s commonly mistaken for ramps, but ramps have a strong onion or garlic smell, while false hellebore is odorless and later grows a tall flower stalk. The plant is highly toxic, and eating any part can cause nausea, a slowed heart rate, and even death due to its alkaloids that affect the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Death Camas (Zigadenus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild onion or wild garlic (Allium spp.)

Death camas is a slender, grass-like plant that grows from underground bulbs and is found in open woods, meadows, and grassy hillsides. It has small, cream-colored flowers in loose clusters atop a tall stalk.

It’s often confused with wild onion or wild garlic due to their similar narrow leaves and habitats, but only Allium plants have a strong onion or garlic scent, while death camas has none. The plant is extremely poisonous, especially the bulbs, and even a small amount can cause nausea, vomiting, a slowed heartbeat, and potentially fatal respiratory failure.

Buckthorn Berries (Rhamnus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Elderberries (Sambucus spp.)

Buckthorn is a shrub or small tree often found along woodland edges, roadsides, and disturbed areas. It produces small, round berries that ripen to dark purple or black and usually grow in loose clusters.

These berries are sometimes mistaken for elderberries and other wild fruits, which also grow in dark clusters, but elderberries form flat-topped clusters on reddish stems while buckthorn berries are more scattered. Buckthorn berries are unsafe to eat as they contain compounds that can cause cramping, vomiting, and diarrhea, and large amounts may lead to dehydration and serious digestive problems.

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Mayapple is a low-growing plant found in shady forests and woodland clearings. It has large, umbrella-like leaves and produces a single pale fruit hidden beneath the foliage.

The unripe fruit resembles a small green grape, causing confusion with wild grapes, which grow in woody clusters on vines. All parts of the mayapple are toxic except the fully ripe, yellow fruit, which is only safe in small amounts. Eating unripe fruit or other parts can lead to nausea, vomiting, and severe dehydration.

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Virginia creeper is a fast-growing vine found on fences, trees, and forest edges. It has five leaflets per stem and produces small, bluish-purple berries from late summer to fall.

It’s often confused with wild grapes since both are climbing vines with similar berries, but grapevines have large, lobed single leaves and tighter fruit clusters. Virginia creeper’s berries are toxic to humans and contain oxalate crystals that can cause nausea, vomiting, and throat irritation.

Castor Bean (Ricinus communis)

Often mistaken for: Wild rhubarb (Rumex spp. or Rheum spp.)

Castor bean is a bold plant with large, lobed leaves and tall red or green stalks, often found in gardens, along roadsides, and in disturbed areas in warmer regions in the US. Its red-tinged stems and overall size can resemble wild rhubarb to the untrained eye.

Unlike rhubarb, castor bean plants produce spiny seed pods containing glossy, mottled seeds that are extremely toxic. These seeds contain ricin, a deadly compound even in small amounts. While all parts of the plant are toxic, the seeds are especially dangerous and should never be handled or ingested.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

How to Get the Best Results Foraging

Safety should always come first when it comes to foraging. Whether you’re in a rural forest or a suburban greenbelt, knowing how to harvest wild foods properly is a key part of staying safe and respectful in the field.

Always Confirm Plant ID Before You Harvest Anything

Knowing exactly what you’re picking is the most important part of safe foraging. Some edible plants have nearly identical toxic lookalikes, and a wrong guess can make you seriously sick.

Use more than one reliable source to confirm your ID, like field guides, apps, and trusted websites. Pay close attention to small details. Things like leaf shape, stem texture, and how the flowers or fruits are arranged all matter.

Not All Edible Plants Are Safe to Eat Whole

Just because a plant is edible doesn’t mean every part of it is safe. Some plants have leaves, stems, or seeds that can be toxic if eaten raw or prepared the wrong way.

For example, pokeweed is only safe when young and properly cooked, while elderberries need to be heated before eating. Rhubarb stems are fine, but the leaves are poisonous. Always look up which parts are edible and how they should be handled.

Avoid Foraging in Polluted or Contaminated Areas

Where you forage matters just as much as what you pick. Plants growing near roads, buildings, or farmland might be coated in chemicals or growing in polluted soil.

Even safe plants can take in harmful substances from the air, water, or ground. Stick to clean, natural areas like forests, local parks that allow foraging, or your own yard when possible.

Don’t Harvest More Than What You Need

When you forage, take only what you plan to use. Overharvesting can hurt local plant populations and reduce future growth in that area.

Leaving plenty behind helps plants reproduce and supports wildlife that depends on them. It also ensures other foragers have a chance to enjoy the same resources.

Protect Yourself and Your Finds with Proper Foraging Gear

Having the right tools makes foraging easier and safer. Gloves protect your hands from irritants like stinging nettle, and a good knife or scissors lets you harvest cleanly without damaging the plant.

Use a basket or breathable bag to carry what you collect. Plastic bags hold too much moisture and can cause your greens to spoil before you get home.

This forager’s toolkit covers the essentials for any level of experience.

Watch for Allergic Reactions When Trying New Wild Foods

Even if a wild plant is safe to eat, your body might react to it in unexpected ways. It’s best to try a small amount first and wait to see how you feel.

Be extra careful with kids or anyone who has allergies. A plant that’s harmless for one person could cause a reaction in someone else.

Check Local Rules Before Foraging on Any Land

Before you start foraging, make sure you know the rules for the area you’re in. What’s allowed in one spot might be completely off-limits just a few miles away.

Some public lands permit limited foraging, while others, like national parks, usually don’t allow it at all. If you’re on private property, always get permission first.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

Where to Find Forageables in the State

There is a range of foraging spots where edible plants grow naturally and often in abundance:

| Plant | Locations |

|---|---|

| Amaranth (Amaranthus retroflexus) | – Agricultural fields in York County – Waste areas in North Platte – Irrigation canals near Scottsbluf |

| American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | – Indian Cave State Park, Richardson County – Wilderness Park, Lincoln – Fontenelle Forest, Bellevue |

| Burdock (Arctium minus) | – Along trails in Ponca State Park – Ditches near Kearney – Edges of fields in Norfolk |

| Butternut (Juglans cinerea) | – Forested areas near Nebraska City – Stream terraces in Brownville – Slopes of Missouri River bluffs, Rulo |

| Cattail (Typha spp.) | – Marshes in Valentine National Wildlife Refuge – Edges of Lake McConaughy – Wetlands near Fremont |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | – Lawns in downtown Omaha – Gardens in Hastings – Open woodlands near Beatrice |

| Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) | – Niobrara State Park – Pine Ridge area near Chadron – Along the Platte River near Columbus |

| Common Mallow (Malva neglecta) | – Vacant lots in Grand Island – Sidewalk cracks in North Platte – Edges of parking lots in Scottsbluff |

| Currant (Ribes spp.) | – Understory of forests in Fort Robinson State Park – Hillsides near Chadron – Along creeks in Seward County |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | – Lawns in Lincoln – Parks in Kearney – Roadside verges in Alliance |

| Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) | – Along Salt Creek in Lincoln – Wooded areas near Bellevue – Edges of wetlands in Norfolk |

| Field Pennycress (Thlaspi arvense) | – Abandoned fields near York – Roadside ditches in Ogallala – Vacant lots in Beatrice |

| Gooseberry (Ribes missouriense) | – Forested areas in Indian Cave State Park – Understory near Valentine – Along streams in Gage County |

| Ground Cherry (Physalis longifolia) | – Sandy soils near Scottsbluff – Grasslands in Holt County – Fields near McCook |

| Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) | – Along Missouri River bluffs near Rulo – Urban areas in Omaha – Wooded parks in Fremont |

| Hickory Nut (Carya spp.) | – Forested areas in Indian Cave State Park – Woodlands near Plattsmouth – Along Elkhorn River near Waterloo |

| Horsemint / Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) | – Prairies in Pawnee County – Meadows near Broken Bow – Grasslands in Dixon County |

| Indian Ricegrass (Achnatherum hymenoides) | – Sandhills near Valentine – Dunes in Cherry County – Sandy soils near Thedford |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | – Along Platte River near Grand Island – Ditches in Lancaster County – Fields near Columbus |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | – Gardens in Lincoln – Fields in Dawson County – Vacant lots in Sidney |

| Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) | – Roadsides near Kearney – Fields in Butler County – Prairies near Norfolk |

| Mulberry (Morus rubra) | – Urban areas in Omaha – Parks in Lincoln – Along rivers in Bellevue |

| Nettle (Urtica dioica) | – Moist woods near Beatrice – Along streams in Custer County – Shaded areas in Gering |

| Nodding Onion (Allium cernuum) | – Rocky outcrops in Pine Ridge – Hillsides near Chadron – Prairies in Sioux County |

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | – Forested areas in Indian Cave State Park – Woodlands near Brownville – Shaded valleys in Nemaha County |

| Pecan (Carya illinoinensis) | – Along Missouri River near Rulo – Wooded areas in Richardson County – Forests near Falls City |

| Plantain (Plantago major) | – Lawns in Hastings – Sidewalk edges in York – Parks in North Platte |

| Purslane (Portulaca oleracea) | – Gardens in Scottsbluff – Sidewalk cracks in Lincoln – Fields near Holdrege |

| Red Clover (Trifolium pratense) | – Pastures in Seward County – Meadows near Aurora – Fields in Butler County |

| Rose Hips (Rosa spp.) | – Along trails in Ponca State Park – Wooded areas near Bellevue – Edges of fields in Gage County |

| Sand Cherry (Prunus pumila) | – Sandy areas near Ogallala – Dunes in Cherry County – Sandhills near Valentine |

| Salsify (Tragopogon spp.) | – Roadsides in Kearney – Fields near North Platte – Vacant lots in Hastings |

| Shepherd’s Purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris) | – Gardens in Lincoln – Fields in Dawson County – Roadsides near Beatrice |

| Smartweed (Polygonum spp.) | – Wetlands near Fremont – Along rivers in Norfolk – Marshy areas in Lancaster County |

| Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) | – Fields near Grand Island – Roadsides in York County – Prairies near Broken Bow |

| Violet (Viola spp.) | – Shaded lawns in Omaha – Woodlands near Beatrice – Parks in Lincoln |

| White Clover (Trifolium repens) | – Lawns in Hastings – Pastures in Seward County – Fields near North Platte |

| Wild Garlic (Allium vineale) | – Fields near McCook – Roadsides in Butler County – Gardens in Lincoln |

| Wild Grape (Vitis riparia) | – Along Missouri River near Rulo – Wooded areas in Bellevue – Forests near Plattsmouth |

| Wild Lettuce (Lactuca canadensis) | – Fields near York – Roadsides in Kearney – Vacant lots in Grand Island |

| Wild Onion (Allium canadense) | – Meadows near Beatrice – Fields in Butler County – Gardens in Lincoln |

| Wild Plum (Prunus americana) | – Along trails in Ponca State Park – Wooded areas near Bellevue – Edges of fields in Gage County |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis spp.) | – Lawns in Omaha – Gardens in Hastings – Parks in Lincoln |

| Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | – Forested areas in Indian Cave State Park – Woodlands near Plattsmouth – Along Elkhorn River near Waterloo |

Peak Foraging Seasons

Different edible plants grow at different times of year, depending on the season and weather. Timing your search makes all the difference.

Spring

Spring brings a fresh wave of wild edible plants as the ground thaws and new growth begins:

| Plant (Latin name) | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | March–May | Cool, shaded garden beds and lawns |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | March–May | Cool, damp lawns and meadows |

| Nettle (Urtica dioica) | April–May | Moist, rich soils near streams |

| Plantain (Plantago major) | April–May | Compacted soils along paths and lawns |

| Ramps (Allium tricoccum) | April–May | Moist, shaded forest floors |

| Shepherd’s Purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris) | March–May | Disturbed soils in gardens and fields |

| Wild Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis) | April–May | Sunny days after spring rains along ditches and fence rows |

| Wild Garlic (Allium vineale) | March–May | Sunny fields and disturbed areas |

| Wild Onion (Allium canadense) | March–May | Sunny, well-drained soils in open areas |

| Wild Violet (Viola spp.) | March–May | Shaded woodland edges and lawns |

Summer

Summer is a peak season for foraging, with fruits, flowers, and greens growing in full force:

| Plant (Latin name) | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Amaranth (Amaranthus retroflexus) | July–August | Sunny, disturbed soils along roadsides and fields |

| Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) | July–August | Moist, sunny areas near streams and forest edges |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | June–August | Sunny, disturbed soils in gardens and fields |

| Mulberry (Morus rubra) | June–July | Sunny areas along forest edges |

| Purslane (Portulaca oleracea) | June–August | Hot, dry areas like sidewalks and garden beds |

| Red Clover (Trifolium pratense) | June–August | Sunny meadows and pastures |

| Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) | July–August | Sunny fields and roadsides |

| White Clover (Trifolium repens) | June–August | Moist lawns and grassy areas |

| Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) | July–August | Sunny prairies and open woodlands |

| Wild Grape (Vitis riparia) | July–August | Sunny, wooded areas and fence lines |

Fall

As temperatures drop, many edible plants shift underground or produce their last harvests:

| Plant (Latin name) | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | September–October | Sunny, open woodlands and riverbanks |

| Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) | August–September | Sunny, open areas and forest margins |

| Ground Cherry (Physalis longifolia) | August–September | Sunny, sandy soils in fields and roadsides |

| Hickory Nut (Carya spp.) | September–October | Mature forests with well-drained soils |

| Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum) | September | Shaded woodlands with moist soils |

| Rose Hips (Rosa spp.) | September–October | Sunny, open fields and forest edges |

| Sand Cherry (Prunus pumila) | August–September | Sandy soils in open prairies and dunes |

| Smartweed (Polygonum spp.) | September–October | Moist areas near streams and wetlands |

| Wild Lettuce (Lactuca canadensis) | September–October | Disturbed soils in fields and roadsides |

| Wild Plum (Prunus americana) | August–September | Sunny thickets and forest edges |

Winter

Winter foraging is limited but still possible, with hardy plants and preserved growth holding on through the cold:

| Plant (Latin name) | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Acorns (Quercus spp.) | December–February | Forest floors beneath oak trees |

| Cattail (Typha spp.) | December–February | Frozen wetlands and marshes |

| Clover (Trifolium spp.) | December–February | Snow-free lawns and fields |

| Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | December–January | Leafless trees with remaining fruit |

| Pine Needles (Pinus spp.) | December–February | Evergreen forests with accessible branches |

| Rose Hips (Rosa spp.) | December–February | Snow-covered fields and forest edges |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | December–February | Cold, flowing streams and springs |

| Wild Onion (Allium canadense) | December–February | Sunny, well-drained soils in open areas |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.