Maine is home to a diverse range of forageable edible plants, many of which change with the seasons. Wintergreen berries, with their glossy leaves and red fruit, grow in cooler months and are often overlooked. Fiddleheads appear briefly but are one of the region’s most well-known wild vegetables.

Not every edible plant here is obvious at first glance. Staghorn sumac produces crimson clusters that have culinary uses, especially in drinks and spice blends. Even tree species like red maple can offer useful edible parts during the right time of year.

Some plants here are gathered fresh, others stored or preserved for later use. If you’re looking for flavor and versatility, wild foods in Maine offer both. The more you discover, the easier it becomes to come home with a wide range of foraged ingredients.

What We Cover In This Article:

- The Edible Plants Found in the State

- Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

- How to Get the Best Results Foraging

- Where to Find Forageables in the State

- Peak Foraging Seasons

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

The Edible Plants Found in the State

Wild plants found across the state can add fresh, seasonal ingredients to your meals:

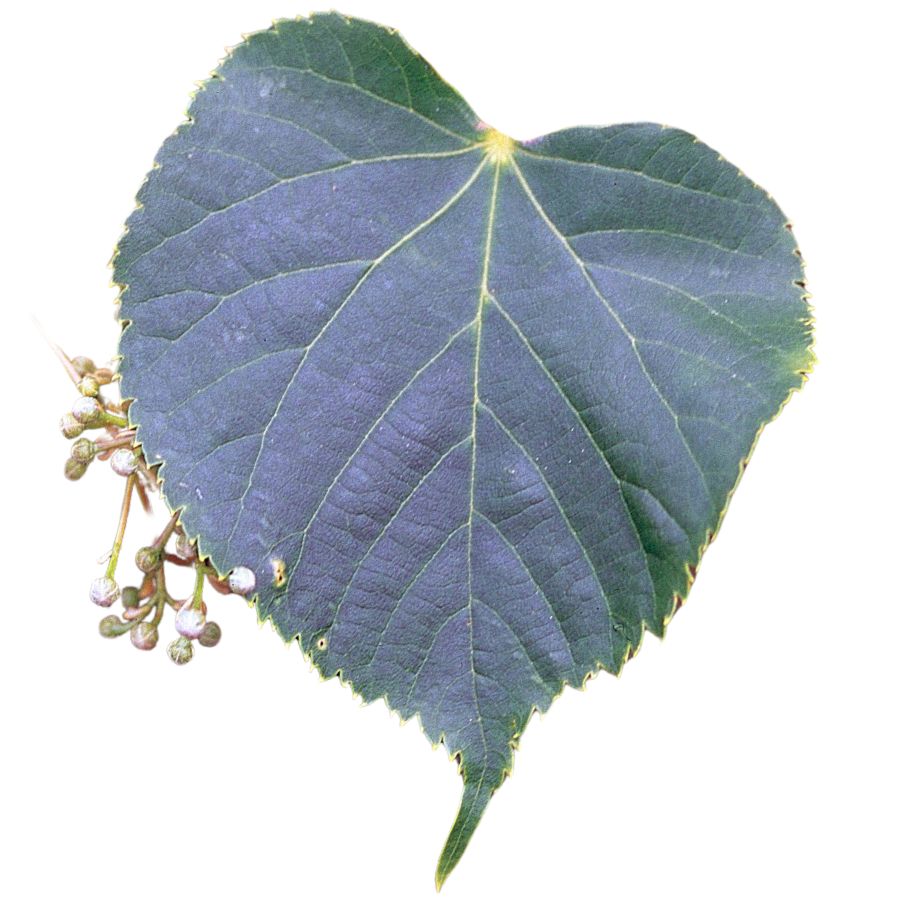

Basswood (Tilia americana)

Basswood, also called bee tree or American linden, produces soft, pale green leaves that are edible when young and still slightly translucent. These leaves taste delicate and slightly mucilaginous, making them good raw in sandwiches or shredded into a salad.

The flowers can be brewed into a calming tea, but they also work as a fragrant garnish for cold desserts or infused honey. Some foragers even grind the seeds to make a coarse nut-flavored paste, though it spoils quickly.

Don’t confuse it with catalpa, which has larger leaves and long bean-like seed pods instead of rounded nutlets. Catalpa leaves are also thicker, odorless when crushed, and lack basswood’s small serrations.

Edible parts include the leaves, inner bark, flowers, and seeds, while the wood and mature bark should be avoided entirely. If you’re harvesting for a meal, stick with parts that snap cleanly and have a slight stickiness—that’s a good sign of freshness.

Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album)

Lamb’s quarters, also called wild spinach and pigweed, has soft green leaves that often look dusted with a white, powdery coating. The leaves are shaped a little like goose feet, with slightly jagged edges and a smooth underside that feels almost velvety when you touch it.

A few plants can be confused with lamb’s quarters, like some types of nightshade, but true lamb’s quarters never have berries and its leaves are usually coated in that distinctive white bloom. Always check that the stems are grooved and not round and smooth like the poisonous lookalikes.

When you taste lamb’s quarters, you will notice it has a mild, slightly nutty flavor that gets richer when cooked. The young leaves, tender stems, and even the seeds are all edible, but you should avoid eating the older stems because they become tough and stringy.

People often sauté lamb’s quarters like spinach, blend it into smoothies, or dry the leaves for later use in soups and stews. It is also rich in oxalates, so you will want to cook it before eating large amounts to avoid any problems.

Red Raspberry (Rubus idaeus)

The red raspberry, also called wild raspberry or bramble raspberry, grows on prickly, arching canes with compound leaves and clusters of red drupelets. You’ll usually find them forming loose thickets, with berries that pull away cleanly from the core when ripe.

The fruit is sweet-tart and juicy with a soft, seedy texture, often used in jams, jellies, or baked into pies. Leaves and stems aren’t edible and shouldn’t be consumed.

While it looks a lot like wineberry or thimbleberry, red raspberry’s hollow core and matte, soft drupelets help separate it from those. Wineberries, in particular, have a shiny, sticky coating and red bristles on their stems.

Unwashed berries can sometimes host small insects or eggs, so rinse them thoroughly before eating or preserving. The fruit can also be frozen or dried for later use, though fresh is when it’s most flavorful.

Red Maple (Acer rubrum)

Red maple offers edible seeds and bark, both of which require basic preparation before eating. The seeds can be boiled, roasted, or ground into a coarse meal, with a texture a bit like roasted pumpkin seeds.

You’ll recognize the tree by its symmetrical, lobed leaves and reddish twigs. The bark of young trees peels cleanly and can be used as a survival food, though it’s best dried and cooked first.

Avoid confusing red maple with Norway maple, which has milky sap when the leaf stem is broken and a more leathery feel to its leaves. That species isn’t toxic, but it’s not harvested for food.

The taste of red maple seeds is mild, slightly bitter if raw, but improves with dry heat. Don’t eat the leaves or old bark—neither has any culinary use and they’re too tough to digest.

Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina)

The edible part of staghorn sumac is the hairy, red fruit cluster that forms a cone shape at the tip of its branches. These clusters are packed with malic acid, giving them a tart flavor that’s perfect for making infused drinks.

Some people confuse it with poison sumac, but poison sumac has drooping white berries and lacks the fuzzy stems of staghorn sumac. That visual difference is critical when deciding what’s safe to forage.

After soaking the berry clusters in water, strain the result through a cloth or coffee filter to remove the irritating surface hairs. The liquid has a lemony bite that pairs well with honey or mint.

You can also dry the clusters and grind them into a reddish powder used like sumac spice in Middle Eastern dishes. Stick to the fruit only—none of the other parts are edible.

Sweet Birch (Betula lenta)

When you snap a twig from sweet birch, that sharp wintergreen smell should hit immediately—this is the edible part you want to work with. Both the twigs and the inner bark are used to flavor teas, confections, and syrups.

Its taste is fresh and minty, especially when steeped, though the raw twigs have a woody chew. The bark can be simmered into a drink with a warming edge, often used historically in traditional root beer-style preparations.

Lookalikes include black cherry and other birches, but none of them have that same fragrant signature—no scent means no dice. Don’t ever rely on just the bark appearance to make the call.

You shouldn’t try to extract oils from sweet birch at home, as doing so can concentrate compounds that are dangerous in large amounts. Stick with infusions and teas, which safely capture the plant’s unique, cooling flavor.

Groundnut (Apios americana)

Groundnut is also called potato bean or Indian potato, and it grows as a climbing vine with clusters of pinkish-purple flowers. The part most people go for is the underground tuber, which looks a bit like a small, knobby chain of beads.

The flavor is richer than a regular potato, with a nutty, earthy taste and a dense, almost chestnut-like texture when cooked. It holds up well in soups and stews, or you can boil and mash it like a root vegetable.

Some people slice it thin and roast it until crisp, while others slow-cook it to bring out a sweeter taste. The vine also produces beans, but the root is what’s usually eaten.

There are a few vines that resemble groundnut, but many of those don’t have the same distinctive flower clusters or tend to lack the beadlike roots. Always make sure you’re digging up the right plant before cooking it.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

Bright yellow flowers and jagged, deeply toothed leaves make dandelions easy to spot in open fields, lawns, and roadsides. You might also hear them called lion’s tooth, blowball, or puffball once the flowers turn into round, white seed heads.

Every part of the dandelion is edible, but you will want to avoid harvesting from places treated with pesticides or roadside areas with heavy car traffic. Besides being a food source, dandelions have been used traditionally for simple herbal remedies and natural dye projects.

Young dandelion leaves have a slightly bitter, peppery flavor that works well in salads or sautés, and the flowers can be fried into fritters or brewed into tea. Some people even roast the roots to make a coffee substitute with a rich, earthy taste.

One thing to watch out for is cat’s ear, a common lookalike with hairy leaves and branching flower stems instead of a single, hollow one. To make sure you have a true dandelion, check for a smooth, hairless stem that oozes a milky sap when broken.

Lowbush Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

Blueberry, sometimes called highbush or lowbush blueberry depending on the type, grows as a shrub with smooth-edged, oval leaves and clusters of small white or pinkish bell-shaped flowers. The berries start green and ripen to a deep blue with a dusty-looking skin that easily rubs off.

A few lookalikes can confuse foragers, like the berries of Virginia creeper or pokeweed, but the differences are clear when you know what to check. True blueberries grow on woody shrubs and have a five-pointed crown on the bottom of each berry, while dangerous lookalikes often grow on vines or have no crown at all.

Blueberries have a sweet, sometimes tangy flavor and a juicy texture that makes them great for fresh eating. You can also bake them into pies, simmer them into jams, or dry them for snacks.

Only the ripe berries are eaten, while the leaves and stems are usually left alone.

Interestingly, blueberries is that they contain natural pigments that can turn recipes and even your fingers a deep purple when handled.

Cattail (Typha latifolia)

Cattails, often called bulrushes or corn dog grass, are easy to spot with their tall green stalks and brown, sausage-shaped flower heads. They grow thickly along the edges of ponds, lakes, and marshes, forming dense stands that are hard to miss.

Almost every part of the cattail is edible, including the young shoots, flower heads, and starchy rhizomes. You can eat the tender shoots raw, boil the flower heads like corn on the cob, or grind the rhizomes into flour for baking.

Besides food, cattails have long been used for making mats, baskets, and even insulation by weaving the dried leaves and using the fluffy seeds. Their combination of usefulness and abundance has made them an important survival plant for many cultures.

One thing you need to watch for is young cattail shoots being confused with similar-looking plants like iris, which are toxic. A real cattail shoot will have a mild cucumber-like smell when you snap it open, while iris plants smell bitter or unpleasant.

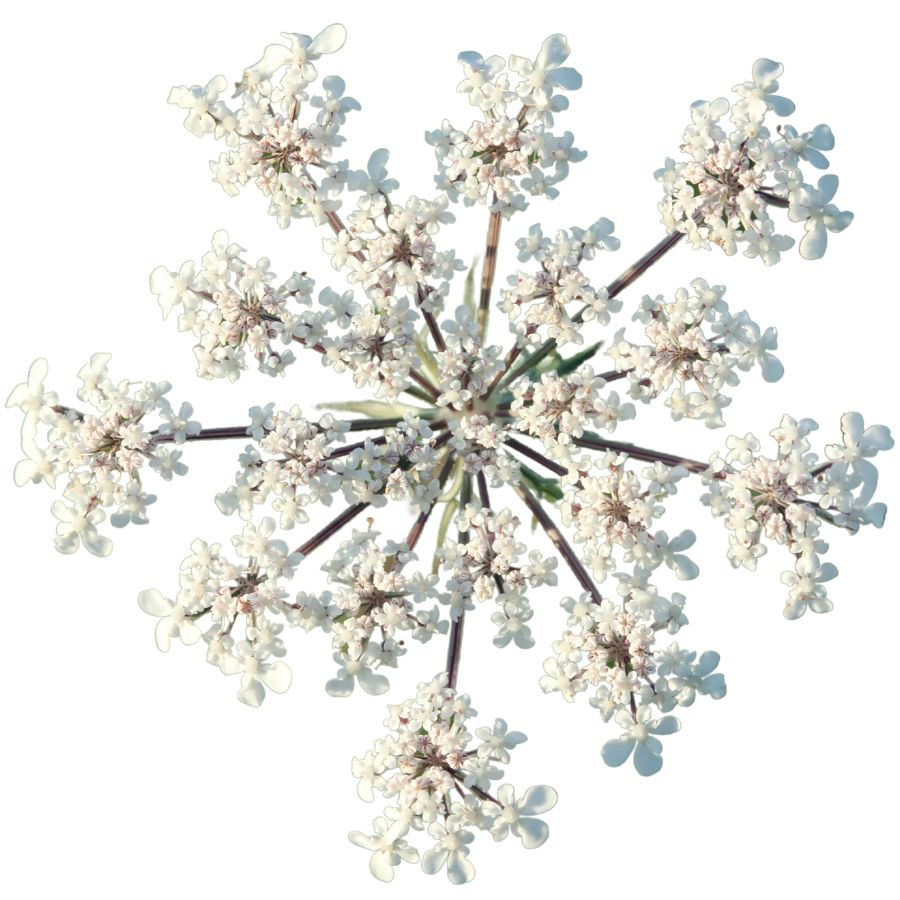

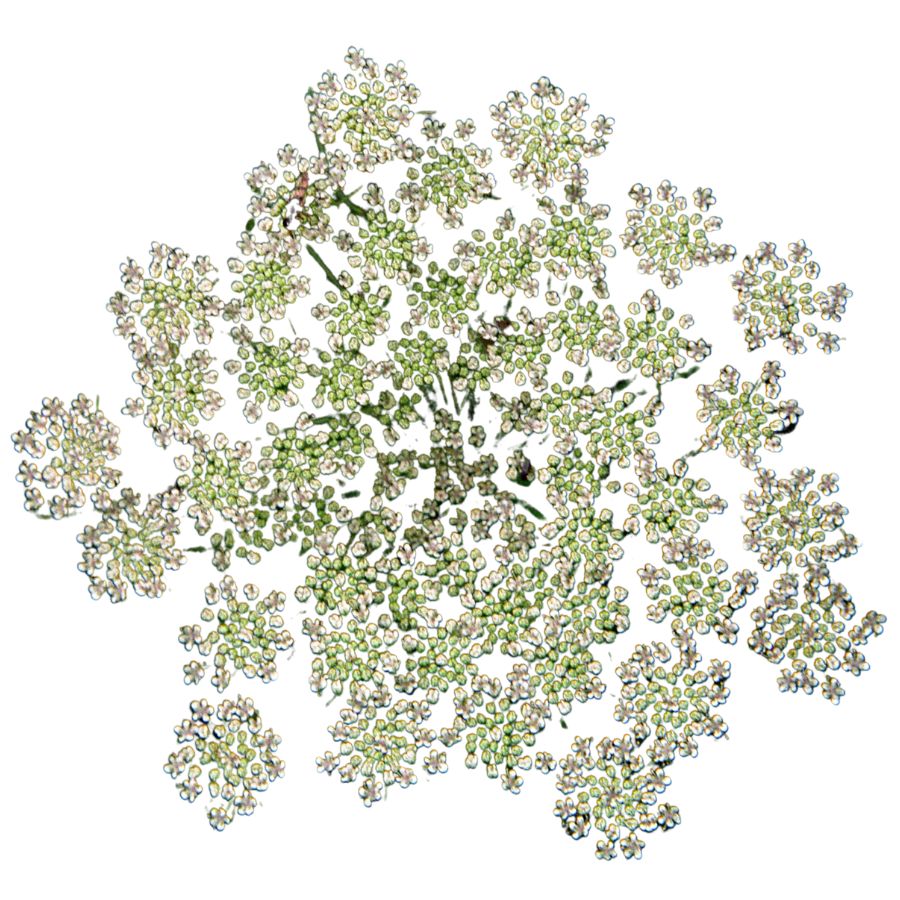

Wild Carrot (Daucus carota)

Wild carrot, which you might know as Queen Anne’s lace, grows a slender, white taproot that’s tough and fibrous when mature. When it’s young, the root has a faint carrot scent and a slightly earthy taste that comes through best when boiled or slow-roasted.

The most dangerous thing about wild carrot is how closely it resembles poison hemlock, which has smooth, hairless stems with purple blotches. Wild carrot has fine hairs along its stems and a single dark floret in the center of its flat white flower clusters.

If you’re going to try it, stick to the root and avoid the leaves and stems, which can cause skin irritation in some people. The root is usually peeled, chopped, and cooked like a tougher version of a garden carrot, but don’t expect it to be sweet.

One interesting trait is how the flower head curls into a tight, nest-like shape as it matures. This plant’s close relatives include common garden carrots, but wild ones grow thinner, drier, and with a much stronger flavor.

Blackberry (Rubus allegheniensis)

Blackberry, also known as brambleberry or dewberry, grows on thick, thorny canes that can arch and spread across the ground. The leaves are usually serrated, and the fruit ripens from green to red before turning deep purple or black when fully ready to pick.

The berries have a sweet, tangy flavor with a soft, juicy texture that easily bursts in your mouth. You can eat them raw, bake them into pies and cobblers, or preserve them by making jams and jellies.

Only the ripe fruit of the blackberry plant is edible, while the stems and leaves are not usually eaten.

Some plants like black raspberry can look similar, but black raspberries are hollow in the center when picked while blackberries have a solid core. It’s important to avoid confusing blackberries with nightshade berries, which grow on upright plants without thorny vines and can be toxic.

An interesting thing about blackberries is that they are technically not a single berry but a cluster of small drupelets packed together.

American Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon)

American cranberries grow on trailing vines and produce firm, round berries that turn deep red when mature. The flesh is tart, slightly woody, and not sweet unless cooked or sweetened.

The closest visual mix-up tends to be with swamp-loving bog rosemary, which looks similar but is toxic and has narrow leaves with rolled edges. Cranberry leaves are broader, leathery, and evergreen, while bog rosemary gives off a medicinal smell when bruised.

People usually boil cranberries into sauces or bake them into bread and cakes after adding sugar or orange zest to cut the bitterness. Drying them with sweetener turns them into chewy snacks with a tangy punch.

Only the fruit is eaten; the rest of the plant isn’t dangerous but has no culinary value. The berry contains a high amount of natural pectin, making it ideal for jellies and thick preserves without added thickeners.

Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

Purslane is a hardy, low-growing plant that’s also sometimes known as little hogweed or verdolaga. It has smooth, reddish stems and thick, paddle-shaped leaves that feel a bit waxy when you touch them.

The stems, leaves, and tiny yellow flowers are all edible, while the roots are not typically eaten. Purslane has a crisp texture with a slightly tart, lemony flavor that works well raw or cooked.

Some plants that look similar include spurge, which has a milky sap and is not edible, so it is important to check for purslane’s smooth, succulent stems and lack of sap. Always double-check by gently snapping a stem to make sure no white liquid appears.

You can toss fresh purslane into salads, sauté it lightly like spinach, or pickle it for later use. Its mild tartness and slight crunch make it a refreshing addition to sandwiches, soups, and even stir-fries.

Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana)

With its jagged green leaves and deep taproot, horseradish has one of the strongest-flavored edible roots you’ll come across. The root delivers a punch of heat that’s more nasal than tongue-based, unlike chili peppers.

Some confuse its leaves with wild burdock or dock, but horseradish gives off a sharp scent when snapped or scratched that those plants lack. The leaves are large and veined, but they’re not the main attraction.

Grated horseradish is typically pickled or added to sauces like cocktail sauce or horseradish cream for beef dishes. Left raw, it loses potency quickly unless combined with vinegar.

Don’t eat the flowers or stem—they’re technically not harmful, but they offer no flavor and aren’t used in cooking. The root, when properly handled, becomes a powerful ingredient with a crisp texture and eye-watering bite.

Wild Leek / Ramp (Allium tricoccum)

Known as wild leek, ramp, or ramson, this flavorful plant is famous for its broad green leaves and slender white stems. It grows low to the ground and gives off a strong onion-like scent when bruised, which can help you tell it apart from toxic lookalikes like lily of the valley.

If you give it a taste, you will notice a bold mix of onion and garlic flavors, with a tender texture that softens even more when cooked. People often sauté the leaves and stems, pickle the bulbs, or blend them into pestos and soups.

The entire plant can be used for cooking, but the leaves and bulbs are the most prized parts. It is important not to confuse it with similar-looking plants that do not have the signature onion smell when crushed.

Wild leek populations have declined in some areas because of overharvesting, so it is a good idea to only take a few from any given patch. When harvested thoughtfully, these vibrant greens can add a punch of flavor to just about anything you make.

Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana)

Clusters of dark berries hanging from a woody shrub usually indicate chokecherries, especially when the leaves are oval with finely toothed edges. These berries turn from red to deep purple or black when they’re ready to eat.

Chokecherries are rarely eaten raw due to their bitterness, but they shine in cooked recipes like preserves, sauces, or even homemade wine. Boiling the fruit and straining it helps separate the pulp from the inedible seeds.

It’s easy to mix up chokecherries with other wild cherries, but true chokecherries have longer, narrower leaves and a more astringent taste. Avoid anything with rounder, solitary berries or a sweet scent without the signature tartness.

Their texture is slightly gritty around the pit, and the flavor improves significantly with sugar and heat. A strong astringent quality dominates the raw berry, but the processed pulp becomes rich and deeply flavored.

White Pine (Pinus strobus)

White pine has bluish-green needles grouped in clusters of five, and when brewed as tea, they give off a mild lemon-pine aroma with a faint astringency. If you chew the needles directly, expect a chewy texture and a tart, sappy burst that can linger in your mouth.

Only the inner bark and the needles should be eaten; avoid the sap in large quantities, as it can cause digestive upset. The cones are mostly inedible due to their tough scales and tiny seeds.

White pine can be confused with loblolly or Virginia pine, but those have needles in groups of three or two, respectively, and tend to be stiffer or more twisted. Getting the needle grouping right is key to avoiding the wrong tree.

Some people dehydrate the needles and grind them into powder to mix with salt or sugar for seasoning. This is a flavorful way to preserve the citrus-pine character without losing potency.

Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens)

If you find a trailing plant with white-veined, dark green leaves and waxy red berries, you’re probably looking at wintergreen. The plant carries a cool mint-like flavor that lingers on the tongue when you chew the berries or leaves.

Its flavor comes from methyl salicylate, which is safe in small amounts but concentrated enough that it shouldn’t be overused. People often use the leaves to make teas or candy infusions with a crisp, sweet finish.

Only the leaves and berries are edible—avoid eating the woody stems or roots, which are too tough and lack flavor. The berries have a chewy skin and taste like wintermint gum when ripe.

Teaberry is a common nickname for wintergreen’s fruit, which is mildly sweet but more useful for flavoring than for bulk snacking. Indian pipe can grow nearby and resembles it slightly, but it lacks any leaf or mint scent and isn’t edible.

Ostrich Fern Fiddleheads (Matteuccia struthiopteris)

The tightly coiled shoots of ostrich fern are called fiddleheads, and they have a clean, grassy flavor with a texture like asparagus. Only the young, furled fronds are edible—avoid the mature leaves entirely.

Fiddleheads have a distinctive U-shaped groove on the inside of the stem and are covered in a brown, papery husk that rubs off easily. Don’t confuse them with bracken or lady ferns, which either lack the groove or have fuzzy stems.

Many people sauté fiddleheads in butter or olive oil with garlic or lemon, but they can also be pickled or blanched and frozen. Raw consumption isn’t safe—always cook them thoroughly to avoid nausea or foodborne illness.

They contain a modest amount of vitamin C and potassium, and their curled shape has made them a spring delicacy in many food traditions. Look only for the green, tightly coiled tips that are about an inch or two tall—anything older gets bitter and fibrous fast.

Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

There are plenty of wild edibles to choose from, but some toxic native plants closely resemble them. Mistaking the wrong one can lead to severe illness or even death, so it’s important to know exactly what you’re picking.

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild carrot (Daucus carota)

Poison hemlock is a tall plant with lacy leaves and umbrella-like clusters of tiny white flowers. It has smooth, hollow stems with purple blotches and grows in sunny places like roadsides, meadows, and stream banks.

Unlike wild carrot, which has hairy stems and a dark central floret, poison hemlock has a musty odor and no flower center spot. It’s extremely toxic; just a small amount can be fatal, and even touching the sap can irritate the skin.

Water Hemlock (Cicuta spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) or wild celery (Apium spp.)

Water hemlock is a tall, branching plant with umbrella-shaped clusters of small white flowers. It grows in wet places like stream banks, marshes, and ditches, with stems that often show purple streaks or spots.

It can be confused with wild parsnip or wild celery, but its thick, hollow roots have internal chambers and release a yellow, foul-smelling sap when cut. Water hemlock is the most toxic plant in North America, and just a small amount can cause seizures, respiratory failure, and death.

False Hellebore (Veratrum viride)

Often mistaken for: Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

False hellebore is a tall plant with broad, pleated green leaves that grow in a spiral from the base, often appearing early in spring. It grows in moist woods, meadows, and along streams.

It’s commonly mistaken for ramps, but ramps have a strong onion or garlic smell, while false hellebore is odorless and later grows a tall flower stalk. The plant is highly toxic, and eating any part can cause nausea, a slowed heart rate, and even death due to its alkaloids that affect the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Death Camas (Zigadenus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild onion or wild garlic (Allium spp.)

Death camas is a slender, grass-like plant that grows from underground bulbs and is found in open woods, meadows, and grassy hillsides. It has small, cream-colored flowers in loose clusters atop a tall stalk.

It’s often confused with wild onion or wild garlic due to their similar narrow leaves and habitats, but only Allium plants have a strong onion or garlic scent, while death camas has none. The plant is extremely poisonous, especially the bulbs, and even a small amount can cause nausea, vomiting, a slowed heartbeat, and potentially fatal respiratory failure.

Buckthorn Berries (Rhamnus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Elderberries (Sambucus spp.)

Buckthorn is a shrub or small tree often found along woodland edges, roadsides, and disturbed areas. It produces small, round berries that ripen to dark purple or black and usually grow in loose clusters.

These berries are sometimes mistaken for elderberries and other wild fruits, which also grow in dark clusters, but elderberries form flat-topped clusters on reddish stems while buckthorn berries are more scattered. Buckthorn berries are unsafe to eat as they contain compounds that can cause cramping, vomiting, and diarrhea, and large amounts may lead to dehydration and serious digestive problems.

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Mayapple is a low-growing plant found in shady forests and woodland clearings. It has large, umbrella-like leaves and produces a single pale fruit hidden beneath the foliage.

The unripe fruit resembles a small green grape, causing confusion with wild grapes, which grow in woody clusters on vines. All parts of the mayapple are toxic except the fully ripe, yellow fruit, which is only safe in small amounts. Eating unripe fruit or other parts can lead to nausea, vomiting, and severe dehydration.

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Virginia creeper is a fast-growing vine found on fences, trees, and forest edges. It has five leaflets per stem and produces small, bluish-purple berries from late summer to fall.

It’s often confused with wild grapes since both are climbing vines with similar berries, but grapevines have large, lobed single leaves and tighter fruit clusters. Virginia creeper’s berries are toxic to humans and contain oxalate crystals that can cause nausea, vomiting, and throat irritation.

Castor Bean (Ricinus communis)

Often mistaken for: Wild rhubarb (Rumex spp. or Rheum spp.)

Castor bean is a bold plant with large, lobed leaves and tall red or green stalks, often found in gardens, along roadsides, and in disturbed areas in warmer regions in the US. Its red-tinged stems and overall size can resemble wild rhubarb to the untrained eye.

Unlike rhubarb, castor bean plants produce spiny seed pods containing glossy, mottled seeds that are extremely toxic. These seeds contain ricin, a deadly compound even in small amounts. While all parts of the plant are toxic, the seeds are especially dangerous and should never be handled or ingested.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

How to Get the Best Results Foraging

Safety should always come first when it comes to foraging. Whether you’re in a rural forest or a suburban greenbelt, knowing how to harvest wild foods properly is a key part of staying safe and respectful in the field.

Always Confirm Plant ID Before You Harvest Anything

Knowing exactly what you’re picking is the most important part of safe foraging. Some edible plants have nearly identical toxic lookalikes, and a wrong guess can make you seriously sick.

Use more than one reliable source to confirm your ID, like field guides, apps, and trusted websites. Pay close attention to small details. Things like leaf shape, stem texture, and how the flowers or fruits are arranged all matter.

Not All Edible Plants Are Safe to Eat Whole

Just because a plant is edible doesn’t mean every part of it is safe. Some plants have leaves, stems, or seeds that can be toxic if eaten raw or prepared the wrong way.

For example, pokeweed is only safe when young and properly cooked, while elderberries need to be heated before eating. Rhubarb stems are fine, but the leaves are poisonous. Always look up which parts are edible and how they should be handled.

Avoid Foraging in Polluted or Contaminated Areas

Where you forage matters just as much as what you pick. Plants growing near roads, buildings, or farmland might be coated in chemicals or growing in polluted soil.

Even safe plants can take in harmful substances from the air, water, or ground. Stick to clean, natural areas like forests, local parks that allow foraging, or your own yard when possible.

Don’t Harvest More Than What You Need

When you forage, take only what you plan to use. Overharvesting can hurt local plant populations and reduce future growth in that area.

Leaving plenty behind helps plants reproduce and supports wildlife that depends on them. It also ensures other foragers have a chance to enjoy the same resources.

Protect Yourself and Your Finds with Proper Foraging Gear

Having the right tools makes foraging easier and safer. Gloves protect your hands from irritants like stinging nettle, and a good knife or scissors lets you harvest cleanly without damaging the plant.

Use a basket or breathable bag to carry what you collect. Plastic bags hold too much moisture and can cause your greens to spoil before you get home.

This forager’s toolkit covers the essentials for any level of experience.

Watch for Allergic Reactions When Trying New Wild Foods

Even if a wild plant is safe to eat, your body might react to it in unexpected ways. It’s best to try a small amount first and wait to see how you feel.

Be extra careful with kids or anyone who has allergies. A plant that’s harmless for one person could cause a reaction in someone else.

Check Local Rules Before Foraging on Any Land

Before you start foraging, make sure you know the rules for the area you’re in. What’s allowed in one spot might be completely off-limits just a few miles away.

Some public lands permit limited foraging, while others, like national parks, usually don’t allow it at all. If you’re on private property, always get permission first.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

Where to Find Forageables in the State

There is a range of foraging spots where edible plants grow naturally and often in abundance:

| Plant | Locations |

| Blackberry (Rubus allegheniensis) | – Cutler Coast Public Lands – Bradbury Mountain State Park – Bald Mountain Preserve |

| Red Raspberry (Rubus idaeus) | – Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge – Mount Blue State Park – Camden Hills State Park |

| Lowbush Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) | – Donnell Pond Public Lands – Great Wass Island Preserve – Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument |

| American Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) | – Deboullie Public Reserved Land – Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge – Tunk Lake area |

| Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) | – Bigelow Preserve – Kennebec Highlands – Machias River Corridor |

| Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) | – Aroostook National Wildlife Refuge – Rangeley Lake State Park – Mount Agamenticus Conservation Region |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia) | – Baxter State Park – Vaughan Woods State Park – Nahmakanta Public Lands |

| Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) | – Wells Reserve at Laudholm – Swan Island Wildlife Management Area – Sebago Lake Land Reserve |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | – Scarborough Marsh Wildlife Management Area – Androscoggin Riverlands State Park – Kennebunk Plains Preserve |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | – Merrymeeting Fields Preserve – Androscoggin Greenway – Penobscot River corridor (Old Town area) |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | – Acadia National Park – Range Ponds State Park – Reid State Park |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | – Fort Halifax State Historic Site – Eastern Promenade (Portland) – Bangor City Forest |

| Purslane (Portulaca oleracea) | – Crescent Beach State Park – Belfast Rail Trail – Farmington Riverside Area |

| Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) | – Unity Wetlands – Hirundo Wildlife Refuge – Belgrade Lakes Region fields |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | – Scarborough Marsh – Kennebec Estuary Land Trust preserves – Messalonskee Stream Wetlands |

| Wild Leek / Ramp (Allium tricoccum) | – Grafton Notch State Park – Appalachian Trail near Baldpate Mountain – Mahoosuc Public Lands |

| Wild Carrot (Daucus carota) | – Wolfe’s Neck Woods State Park – Fort Foster (Kittery) – Kennebec River Rail Trail |

| Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina) | – Camden Hills State Park – Peaks-Kenny State Park – Frye Mountain Wildlife Management Area |

| White Pine (Pinus strobus) | – Moosehead Lake region – Sebasticook Lake Wildlife Management Area – Baxter State Park |

| Fiddlehead Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) | – Allagash Wilderness Waterway – Penobscot River floodplains near Medway – Kennebec River islands near Skowhegan |

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) | – Wells Barren Preserve – Blue Hill Heritage Trust lands – Holt Pond Preserve |

| Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) | – Gilsland Farm Audubon Center – Orono Bog Boardwalk – Jamies Pond Wildlife Management Area |

| Black Huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata) | – Great Heath Public Reserved Land – Schoodic Peninsula (Acadia) – Chain of Ponds Public Land |

| Pin Cherry (Prunus pensylvanica) | – Little Moose Public Reserved Land – Tumbledown Mountain area – Nahmakanta Public Lands |

| Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) | – Duck Lake Public Lands – Warren Island State Park – Bald Mountain near Oquossoc |

| American Plum (Prunus americana) | – Messalonskee Lake shoreline – Kennebec Highlands – Vaughan Woods Memorial State Park |

| Gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum) | – Camden Hills State Park – Frenchman Bay Conservancy lands – Cranberry Isles (woodland edges) |

| Red Currant (Ribes rubrum) | – Northern Forest Canoe Trail (around Moose River) – Lake Josephine area – Mt. Kineo peninsula |

| Beach Plum (Prunus maritima) | – Ferry Beach State Park – Biddeford Pool barrier dunes – Laudholm Beach |

| Chicory (Cichorium intybus) | – Fort Edgecomb State Historic Site – Kennebunk Bridle Path – Along Route 201 near Skowhegan |

| Sheep Sorrel (Rumex acetosella) | – Wells National Estuarine Research Reserve – Mount Agamenticus trails – Littlejohn Island Preserve |

| Common Sorrel (Rumex acetosa) | – Wolfe’s Neck Center farmland edges – Vaughan Woods Community Trails – Highland Farm Preserve |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | – Unity College trails – Riverside Park in Westbrook – Fort Andross riverwalk area |

| Yellow Dock (Rumex obtusifolius) | – Presumpscot River Preserve – Sandy River trail system – Fields near Machias River Corridor |

| Pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus) | – Old Orchard Beach dunes edge – Fort Kent community areas – Penobscot Riverwalk near Brewer |

| Fireweed (Chamaenerion angustifolium) | – Katahdin Iron Works Historic Site – Pleasant Mountain trails – Baxter State Park (burned clearings) |

| Smooth Sumac (Rhus glabra) | – Auburn Riverwalk – Great Diamond Island – Unity Wetlands fringe zones |

| Red Maple (Acer rubrum) | – Meduxnekeag River Corridor – Seboeis Public Lands – Kennebago River floodplain |

| Sweet Maple (Acer saccharum) | – Bigelow Preserve – Pleasant River Headwaters Forest – Ducktrap River Preserve |

| American Hazelnut (Corylus americana) | – Sandy Point Beach Park – Androscoggin River Trail – Eastern Trail near Scarborough Marsh |

| Basswood (Tilia americana) | – Mount Abram Township woodlands – Great Pond Mountain Wildlands – Seven Ponds Public Reserve |

| Sweet Birch (Betula lenta) | – Nahmakanta Public Lands – Moxie Gore Township trails – Alder Stream Wilderness Preserve |

| Yellow Birch (Betula alleghaniensis) | – Little Lyford Ponds area – Bald Mountain near Weld – Scopan Public Reserved Land |

| Beech (Fagus grandifolia) | – Deboullie Public Reserved Land – Mount Blue State Park – Kennebago Divide region |

| Red Clover (Trifolium pratense) | – Fields near Thomas College Nature Trail – Rockport Meadow Preserve – Fort Point State Park |

| White Clover (Trifolium repens) | – Eastern Trail in Scarborough – Sears Island open fields – Penobscot Narrows State Park |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | – Fields at Damariscotta River Association lands – Belfast Common – Fort McClary Historic Site |

| Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis) | – Sand dunes at Popham Beach State Park – Coastal fields at Biddeford Pool – Wells Barrens Preserve |

| Wild Rose (Rosa virginiana) | – Roque Bluffs State Park – Long Cove Headwaters Preserve – Reid State Park dunes |

| Sweetfern (Comptonia peregrina) | – Pineo Ridge Public Reserved Land – Kennebunk Plains Preserve – Mount Agamenticus Conservation Area |

| Common Plantain (Plantago major) | – Baxter Boulevard (Portland) – Fields at Lamoine State Park – Thomaston Green open space |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | – Salmon Brook Lake Bog Public Land – Southwest corridor of Aroostook State Park – Howard Hill Historic Park (Augusta) |

| Grape (Vitis riparia) | – Androscoggin Riverlands State Park – Fields around Pushaw Lake – Presumpscot River Trail System |

| Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) | – Edge of farmland near Belgrade Lakes – Abandoned homesteads in Litchfield area – Coastal farm edges near Northport |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | – Streams at Wells Reserve at Laudholm – Spring-fed brooks in Fryeburg – Small tributaries near Grand Lake Stream |

| Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | – Back Cove Trail (Portland) – Streambanks at Brown Woods (Bangor) – Forest edges in Brunswick Landing |

Peak Foraging Seasons

Different edible plants grow at different times of year, depending on the season and weather. Timing your search makes all the difference.

Spring

Spring brings a fresh wave of wild edible plants as the ground thaws and new growth begins:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Red Maple (Acer rubrum) | March – April (sap) | Cold nights and warm days during early spring thaw |

| Sweet Maple (Acer saccharum) | March – April (sap) | Ideal during freeze-thaw cycles in early spring |

| Sweet Birch (Betula lenta) | March – May (sap and twigs) | Cold nights and warm days in early spring |

| Yellow Birch (Betula alleghaniensis) | March – May (sap and twigs) | Freeze-thaw cycles with sunny afternoons |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | March – May | Clear, cold water in shaded spring-fed streams |

| Wild Leek / Ramp (Allium tricoccum) | April – May | Cool, damp forest floors with overcast or post-rain conditions |

| Fiddlehead Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) | April – May | Cool spring days, especially after recent rainfall |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | April – May (young leaves) | Moist soil following spring showers |

| Yellow Dock (Rumex obtusifolius) | April – May (young leaves) | Damp, shaded areas with cool temperatures |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | April – May (young leaves and buds) | Warm, damp weather with forest humidity |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | April – June | Mild temperatures, moist soil after rain |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | April – June | Wet, marshy areas during mild, damp conditions |

| Sheep Sorrel (Rumex acetosella) | April – June | Cool, damp conditions with partial sun |

| Common Sorrel (Rumex acetosa) | April – June | Mild, overcast days after rain |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | April – June | Moist, cool conditions and partial shade |

| Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | April – June | Cool, overcast days with recent rainfall |

| Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) | May – June (young shoots) | Warm but not dry, after spring rains |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | May – June (young leaves) | Warm, sunny days after light rainfall |

| Fireweed (Chamaenerion angustifolium) | May – June (young shoots) | Sunny days after early spring rain |

| Basswood (Tilia americana) | May – June (young leaves) | Mild, damp weather with filtered sunlight |

| Beech (Fagus grandifolia) | May – June (young leaves) | Cool, moist spring days with light canopy cover |

| Purslane (Portulaca oleracea) | Late May – June | Warm weather following consistent sun and moderate moisture |

Summer

Summer is a peak season for foraging, with fruits, flowers, and greens growing in full force:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | June (seed pods) | Warm weather with partial shade |

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) | June – July | Warm, sunny weather with well-drained soil |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia) | June – July | Mild to warm temperatures, ideally just after light rains |

| Gooseberry (Ribes hirtellum) | June – July | Cool to warm temperatures with partial sun |

| Red Currant (Ribes rubrum) | June – July | Mild summer days with moist soil |

| Wild Rose (Rosa virginiana) | June – July (flowers and young shoots) | Dry, sunny days with morning dew |

| Red Clover (Trifolium pratense) | June – August | Warm, sunny days after light rain |

| White Clover (Trifolium repens) | June – August | Sunny, grassy areas with steady warmth |

| Sweetfern (Comptonia peregrina) | June – August | Hot, sandy soils and full sun |

| Common Plantain (Plantago major) | June – September | Warm, partly sunny days after rain |

| Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) | June – August (young leaves) | Sunny, post-rain conditions in loose soil |

| Blackberry (Rubus allegheniensis) | July – August | Sunny, dry days following early summer rains |

| Red Raspberry (Rubus idaeus) | July – August | Warm, dry weather with high sun exposure |

| Lowbush Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) | July – August | Sunny and dry, with cool nights for flavor concentration |

| Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) | July – August (flowers & early berries) | Warm, partly cloudy days with moist soil |

| Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) | July – August (flowers & pods) | Hot, sunny days with moderate humidity |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | July – August | Hot and sunny weather, post-thunderstorm soil works best |

| Pin Cherry (Prunus pensylvanica) | July – August | Sunny, dry stretches after early summer rain |

| Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) | July – August | Hot, sunny days with occasional rain |

| Black Huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata) | July – August | Warm, dry conditions in open woods |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | July – August (green flower spikes & young shoots) | Humid with standing water nearby |

| Grape (Vitis riparia) | July – August (young leaves and unripe fruit) | Hot days with moderate humidity |

| Fireweed (Chamaenerion angustifolium) | July – August (flowers) | Sunny and warm, especially in open clearings |

| Purslane (Portulaca oleracea) | July – September | Consistently hot and sunny, thrives in dry heat |

| Wild Carrot (Daucus carota) | July – September | Warm to hot, slightly dry soil improves flavor |

| Pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus) | July – September | Hot, dry weather with disturbed soil exposure |

| Chicory (Cichorium intybus) | July – September | Dry and sunny conditions along field edges |

| Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis) | July – September | Hot, dry weather with open sunlight |

| Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina) | August – September | Warm, dry weather after several sunny days |

| American Plum (Prunus americana) | August | Hot, sunny weather following summer rainfall |

| Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) | August | Dry, sunny days with well-developed fruits |

| Beach Plum (Prunus maritima) | August | Hot, coastal days with little recent rainfall |

Fall

As temperatures drop, many edible plants shift underground or produce their last harvests:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia) | Early September (late harvest) | Mild and dry early fall days |

| American Plum (Prunus americana) | Early September (late harvest) | Mild, dry weather with cool nights |

| Beach Plum (Prunus maritima) | Early September (if late fruiting) | Coastal breezes and dry fall conditions |

| Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina) | September | Dry conditions enhance tartness of seed clusters |

| Basswood (Tilia americana) | September (inner bark) | Cool, dry days before heavy frost |

| American Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) | September – November | Cool nights and sunny days for ripening |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | September – November | Cool and damp soil following early fall rains |

| White Pine (Pinus strobus) | September – November (inner bark, needles) | Dry and cool with low wind exposure |

| Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) | September – October | Sunny fall weather following a dry spell |

| Wild Carrot (Daucus carota) | September – October (roots) | Cool temperatures, ideally after light rain |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | September – October (mature seeds) | Crisp, dry weather with no recent frost |

| American Hazelnut (Corylus americana) | September – October | Cool, dry days following early fall chill |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | September – October (roots) | Crisp, dry conditions after first frosts |

| Yellow Dock (Rumex obtusifolius) | September – October (roots) | Cool weather after light frost for best flavor |

| Smooth Sumac (Rhus glabra) | September – October | Dry, sunny days for optimal tartness |

| Beech (Fagus grandifolia) | September – October (nuts) | Crisp, dry weather with early leaf drop |

| Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis) | September – October (roots) | Cool, dry days after the first frost |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | September – October (berries) | Mild fall days with morning mist |

| Grape (Vitis riparia) | September – October (ripe fruit) | Warm, sunny days with cool nights |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | September – October | Cold, clear streams under cool conditions |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | October – November | Cool, dry days after the first frost |

| Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) | October – November (roots) | Cool, post-frost periods with loosened soil |

Winter

Winter foraging is limited but still possible, with hardy plants and preserved growth holding on through the cold:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| White Pine (Pinus strobus) | December – March (needles, resin) | Cold, dry days; best after snowfall for needle freshness |

| Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) | December – February | Cold, clear days; best for gathering berries above snow |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | December – February (roots) | Frozen marshes or shallow wetland edges, ideally during thaw periods |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | December – January (if ground not frozen) | Cold, post-frost periods; loosened soil during thaws |

| Red Maple (Acer rubrum) | December – February (bark, twigs) | Cold, dry days with low snowpack |

| American Hazelnut (Corylus americana) | December – February (dormant buds, overwintered nuts) | Cold, dry weather with minimal wind exposure |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | December – February (when snow-free) | Mild winter days above freezing in sheltered areas |

| Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) | December – February (if ground isn’t frozen) | Cold, thawing days ideal for root digging |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | December – February | Flowing, unfrozen spring-fed water in cold conditions |

| Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) | January – February (tap preparation) | Freezing nights and sunny days approaching spring |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.