A wide variety of edible plants grow wild across Louisiana, offering more than most people expect. You can bite into a ripe Chickasaw plum in one season and dig up a crisp Jerusalem artichoke in another. Some plants, like horsemint, add a strong, herbal note to simple meals with almost no effort.

You don’t need a garden to find something fresh—just some awareness and a good eye. Smooth sumac, with its bright red clusters, offers a tart kick that surprises first-time tasters. Even common species like lamb’s quarters can be more nutritious than anything from the store.

Once you know what’s out there, your options grow fast. The variety is broad, from delicate greens to starchy roots and aromatic herbs. A walk in the woods can turn into a basket full of flavors you didn’t expect.

What We Cover In This Article:

- The Edible Plants Found in the State

- Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

- How to Get the Best Results Foraging

- Where to Find Forageables in the State

- Peak Foraging Seasons

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

The Edible Plants Found in the State

Wild plants found across the state can add fresh, seasonal ingredients to your meals:

Bramble (Rubus fruticosus)

The fruit of brambles grows in clusters of small, shiny drupelets that form a rounded or slightly conical shape, usually deep black when ripe. They have a juicy, sweet-tart flavor and a seedy texture that’s familiar in pies and jams.

You can also eat the young shoots peeled raw or lightly cooked, though the rest of the stem is covered in thorns and not edible. Bramble leaves are technically edible, but they’re very astringent and more commonly steeped for tea than eaten.

Avoid mistaking black nightshade berries for brambles; nightshade fruits grow singly, have smooth skin, and lack the segmented drupelet structure. While brambles grow on thorny, arching canes, nightshade plants tend to be smaller, herbaceous, and thornless.

Brambles are commonly turned into jam, syrup, or wine, but they’re also good fresh in salads or mashed into sauces. If you’re harvesting, beware the bramble thorns, which can break the skin and cause irritation if you aren’t careful.

Meadow Garlic (Allium canadense)

Meadow garlic, also called wild onion or wild garlic, grows in clumps with slender hollow leaves and small pink or white flowers. You’ll recognize it by the onion scent released when you bruise the stems or dig into the bulb.

The edible parts include the bulbs, stems, leaves, and flowers, all of which have a mild onion flavor and crisp texture. Cook them as you would scallions—sautéed, grilled, or tossed raw into salads.

False garlic, or crow poison, looks similar but lacks the onion smell and can be toxic if eaten. Always crush the plant before harvesting—no onion scent means don’t eat it.

Many people pickle the bulbs or chop the greens for compound butters and dips. Be cautious where you forage it though, as plants growing near roadsides or sprayed areas can absorb contaminants.

American Beautyberry (Callicarpa americana)

American beautyberry, sometimes called French mulberry or sourbush, is highly easily recognizable thanks to its bright clusters of purple berries wrapped tightly around its stems. The plant itself has arching branches and broad, serrated leaves that give off a slight spicy scent when crushed.

The berries are edible and have a mild, slightly sweet flavor with a soft, juicy texture that some people find a little gritty. Only the ripe purple berries should be eaten, as the leaves and unripe berries are not considered edible.

One of the easiest ways to enjoy beautyberries is by making jelly, where the fruit’s subtle taste really shines through. Some people also simmer the berries into syrups or add them to baked goods, although the flavor can be too delicate to stand out without a little help from sugar or lemon.

Beautyberries are sometimes confused with pokeweed, but pokeweed’s berries are a darker purple and grow on red stems in drooping clusters rather than tight whorls. Always double-check the plant’s structure and berry arrangement so you can be sure you are harvesting true American beautyberry.

Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album)

Lamb’s quarters, also called wild spinach and pigweed, has soft green leaves that often look dusted with a white, powdery coating. The leaves are shaped a little like goose feet, with slightly jagged edges and a smooth underside that feels almost velvety when you touch it.

A few plants can be confused with lamb’s quarters, like some types of nightshade, but true lamb’s quarters never have berries and its leaves are usually coated in that distinctive white bloom. Always check that the stems are grooved and not round and smooth like the poisonous lookalikes.

When you taste lamb’s quarters, you will notice it has a mild, slightly nutty flavor that gets richer when cooked. The young leaves, tender stems, and even the seeds are all edible, but you should avoid eating the older stems because they become tough and stringy.

People often sauté lamb’s quarters like spinach, blend it into smoothies, or dry the leaves for later use in soups and stews. It is also rich in oxalates, so you will want to cook it before eating large amounts to avoid any problems.

Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus)

Jerusalem artichoke grows tall with sunflower-like blooms and has knobby underground tubers. The tubers are tan or reddish and look a bit like ginger root, though they belong to the sunflower family.

The part you’re after is the tuber, which has a nutty, slightly sweet flavor and a crisp texture when raw. You can roast, sauté, boil, or mash them like potatoes, and they hold their shape well in soups and stir-fries.

Some people experience gas or bloating after eating sunchokes due to the inulin they contain, so it’s a good idea to try a small amount first. Cooking them thoroughly can help reduce the chances of digestive discomfort.

Sunchokes don’t have many dangerous lookalikes, but it’s important not to confuse the plant with other sunflower relatives that don’t produce tubers. The above-ground part resembles a small sunflower, but it’s the knotted, underground tubers that are worth digging up.

Tall Lettuce (Lactuca virosa)

Tall lettuce, also called wild lettuce or bitter lettuce, has jagged, deeply lobed leaves and a pale green stalk that can reach several feet high. The milky sap inside the stem and leaves is a key identifier—no edible lookalike has the same bitter, latex-like ooze.

The leaves are technically edible raw, but the taste is aggressively bitter and the texture tough, so most people blanch or boil them to take the edge off. Only the young leaves and tender shoots are worth eating; the older parts are fibrous and nearly inedible.

It’s often confused with prickly lettuce, which has similar shape and color but carries tiny spines along the midrib on the underside of the leaf—something tall lettuce lacks. That confusion can be a problem, because not all wild lettuces are edible or safe to eat in quantity.

If you’re preparing it, try cooking it down into greens or mixing it with milder plants to balance the flavor. Don’t bother with the stem unless it’s early and soft—it gets woody fast.

Smooth Sumac (Rhus glabra)

Smooth sumac has deep red fruit clusters that rise above the leaves like upright torches, and these berries are the part you can eat. The fruits have a citrusy tang and are often used to make cold infusions or homemade spice blends.

When chewed, they taste sour and slightly astringent, leaving a dry finish in the mouth. Some people prefer to dry them first before grinding or steeping.

Its only major lookalike, poison sumac, bears drooping, pale berries and prefers wet, swampy ground. The two also differ in branch texture—smooth sumac has fuzzy stems, while poison sumac’s branches are smooth and shiny.

You should only eat the berries; stems, bark, and leaves can cause digestive upset. The flavor comes from an acid-rich coating, not the seeds, so always strain or filter before drinking.

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba)

The pawpaw grows fruits that are green and shaped a little like small mangoes. Inside, the soft yellow flesh tastes like a blend of banana, mango, and melon, with a custard-like texture that melts in your mouth.

If you are comparing it to similar plants, keep in mind that young pawpaw trees can look a little like young magnolias because of their large leaves. True pawpaws grow fruits with large brown seeds tucked inside, while magnolias do not produce anything that looks or tastes similar.

You can eat the flesh straight out of the skin with a spoon, or mash it into puddings, smoothies, and even homemade ice cream. Some people also like to freeze it into cubes for later, although it does tend to brown quickly once exposed to air.

Stick to eating the soft inner flesh. Make sure not to ingest the skin and seeds of the fruit because they contain compounds that can upset your stomach.

This fruit is that it was a favorite snack of Native Americans and early explorers long before it started showing up in backyard gardens.

Spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis)

With three blue or purple petals and yellow-tipped stamens, spiderwort flowers bloom briefly on arching stems above a tangle of grasslike leaves. The plant produces a mucilaginous sap that leaks from any broken stem or leaf.

Both the flowers and the young shoots are edible, and you can toss them into salads or cook them like spinach. The taste is mild and green, with a silky texture when warmed.

Some Tradescantia species used ornamentally aren’t good for eating and can irritate the stomach; avoid plants with fuzzy stems or oddly colored foliage. Stick with clean green leaves and clearly structured flowers when harvesting.

The plant is most often eaten fresh, but you can also ferment the leaves slightly to make a tangy relish. Be sure to wash thoroughly, especially if growing near roads or treated areas.

Horsemint (Monarda citriodora)

The lavender-pink flower spikes of horsemint rise above a base of lance-shaped leaves that smell like lemon when crushed. Its square stems and opposite leaf arrangement mark it as a member of the mint family, which helps set it apart from unrelated lookalikes.

If you confuse horsemint with spotted beebalm, which has pale bracts and a spicier scent, look closely at the flower shape—horsemint’s blooms are more tubular and sharply two-lipped. The edible parts include the flowers and leaves, which can be steeped for tea or added fresh to salads for a citrusy note.

The flavor has a lemony bite with a slightly peppery aftertaste, and the texture is tender when young but toughens with age. Most people dry the leaves to preserve the flavor for later use in herbal infusions or seasoning blends.

Avoid consuming any lookalikes that have no scent or are woody-stemmed, as they may not be safe. Horsemint has also been used in some regional dishes to add brightness, though the taste can overwhelm if you use too much.

Broadleaf Arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia)

The broadleaf arrowhead has large, arrow-shaped leaves and produces edible tubers that grow underwater. These tubers are the main part people eat, often dug up from shallow, muddy spots.

The tubers taste starchy and mild, similar to potatoes, and have a firm, slightly nutty texture when boiled or roasted. You can also slice and dry them to grind into flour or store for later use.

Some species of Sagittaria look similar but produce smaller or bitter tubers, which aren’t good for eating. One way to tell the difference is by checking the size and shape of the tubers—broadleaf arrowhead has rounded, plump ones with crisp white flesh.

Don’t eat the green parts raw, especially the leaves, since they can irritate your digestive system. Stick to cooking the tubers thoroughly, and you’ll have a solid wild food with a long foraging history across North America.

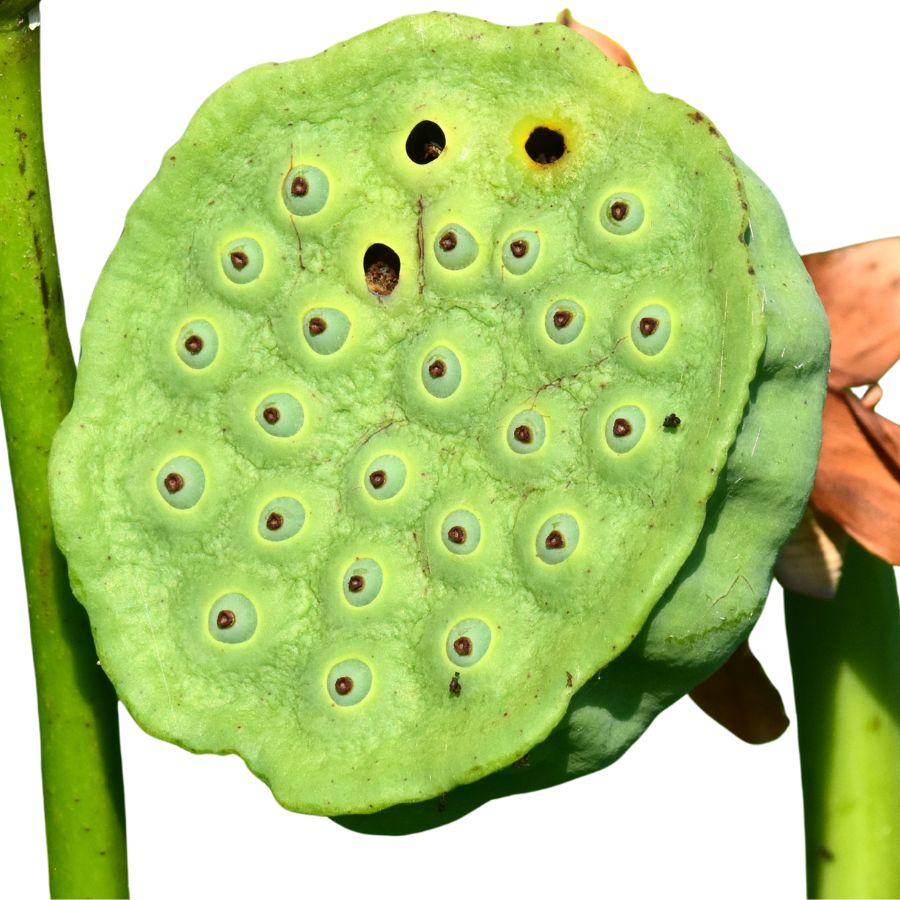

American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea)

The large, round leaves and pale yellow flowers of American lotus grow on long stalks that rise from muddy water, making it easy to gather the edible parts. You can eat the tubers, seeds, and young leaves, all of which are mild and slightly nutty in flavor.

Roasted seeds have a texture like chestnuts and are often used in snacks or ground into flour. The tubers are starchy and soft when boiled or stir-fried, and they take on sauces well.

Some confuse American lotus with water lilies, but lotus leaves are circular and unnotched, while water lily leaves have a split at the base. Water lily roots and seeds aren’t considered edible and may upset your stomach.

Young lotus leaves can be blanched and used as wraps for steamed fillings, but older leaves get tough and stringy. The flowers aren’t toxic, but they’re not typically eaten either.

Eastern Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia humifusa)

The pads of eastern prickly pear cactus are edible after proper preparation, with their slick interior becoming pleasantly tender once grilled or boiled. The fruits, often deep red when ripe, contain small seeds and a juicy pulp with a flavor that’s lightly sweet and subtly earthy.

Avoid confusing it with similar cactus species that have thicker pads and a bitter, soapy taste. Some southwestern species look similar at a glance but are far more fibrous and less palatable.

The best parts to eat are the young, tender pads and the ripe fruit, but every part must be carefully cleaned of spines and tiny glochids. Skip the roots and flowers, which aren’t used as food.

Many people slice and stir-fry the pads with eggs or tomatoes, or use the fruit to make candy or juice. If you’re trying it for the first time, cook a small batch and see how the texture works for you—it can be slightly mucilaginous, like okra.

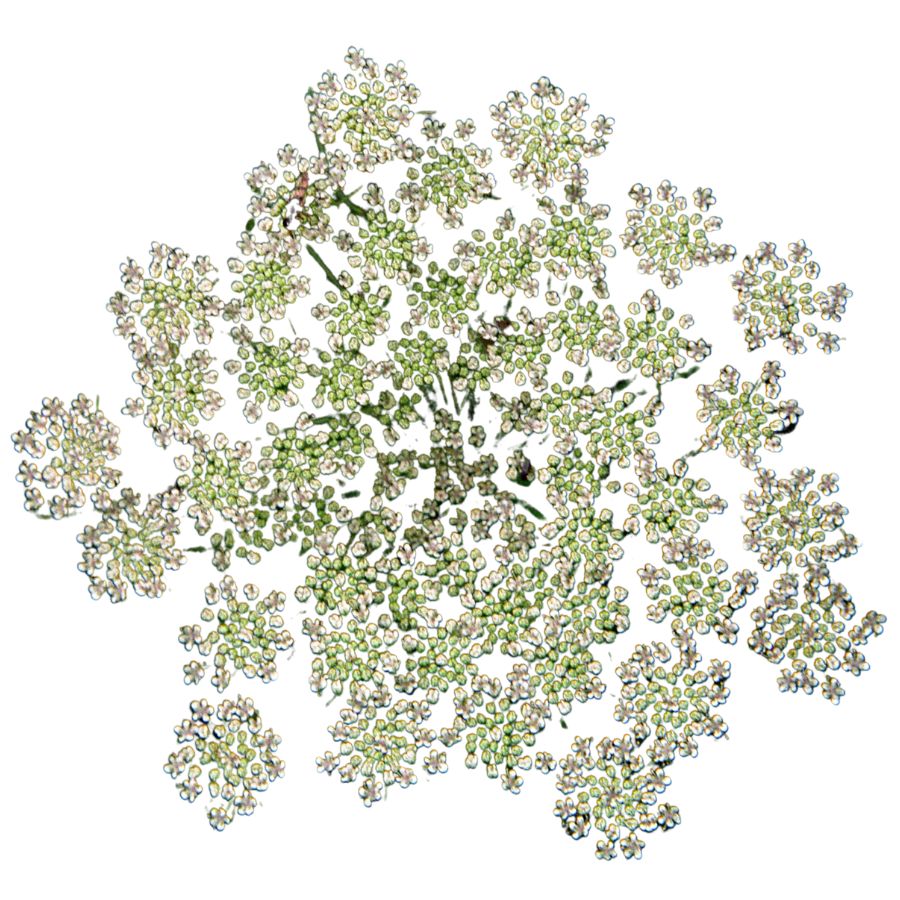

Peppergrass (Lepidium virginicum)

Peppergrass, sometimes called Virginia pepperweed or poor man’s pepper, is a small leafy plant that grows upright with tiny white flowers. The plant’s seed pods are flat, round, and shaped like tiny coins, making them easy to spot once you know what to look for.

You can eat the leaves, young seed pods, and even the flowers of peppergrass. The seed pods are the part most people like to harvest because they have a strong, peppery bite that livens up salads or sandwiches.

Some wild mustards can look a little bit like peppergrass, but their seed pods are usually longer and shaped more like skinny beans. When you are checking the plant, look closely at the flat, disk-shaped pods to make sure you have the right one.

Peppergrass has a spicy flavor that gets sharper as the plant matures, almost like a cross between black pepper and a mild radish. People often use the fresh pods or leaves chopped into salads, or sometimes grind the dried seeds as a seasoning.

Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare)

Wild fennel, sometimes known as sweet fennel or common fennel, is easy to recognize once you know what to look for. It grows tall with feathery, bright green leaves and small clusters of yellow flowers, and the whole plant smells strongly of licorice when crushed.

The frilly leaves, tender stems, seeds, and even the pollen of wild fennel are edible, but the mature stalks can become woody and unpleasant to chew. If you find a plant that looks similar but does not have that distinct sweet smell, it could be poison hemlock, which is deadly and should never be touched or eaten.

The leaves have a delicate, slightly sweet flavor that works well in salads, pestos, or sprinkled fresh over fish and pasta dishes. People often toast the seeds to release their warm, anise-like aroma and use them to flavor breads, sausages, or herbal teas.

Some people also harvest the bright yellow fennel pollen, often called “spice gold,” to use as a luxurious seasoning for meats, vegetables, and desserts.

One interesting thing about wild fennel is that it does not form a fat, bulb-like base the way cultivated fennel does, so you will not find a large white bulb underground.

Red Maple (Acer rubrum)

Red maple offers edible seeds and bark, both of which require basic preparation before eating. The seeds can be boiled, roasted, or ground into a coarse meal, with a texture a bit like roasted pumpkin seeds.

You’ll recognize the tree by its symmetrical, lobed leaves and reddish twigs. The bark of young trees peels cleanly and can be used as a survival food, though it’s best dried and cooked first.

Avoid confusing red maple with Norway maple, which has milky sap when the leaf stem is broken and a more leathery feel to its leaves. That species isn’t toxic, but it’s not harvested for food.

The taste of red maple seeds is mild, slightly bitter if raw, but improves with dry heat. Don’t eat the leaves or old bark—neither has any culinary use and they’re too tough to digest.

Virginia Springbeauty (Claytonia virginica)

The edible part of Virginia springbeauty—called wild potato or fairy spud—is its small underground tuber, often about the size of a marble. It grows just below the base of a cluster of narrow leaves and delicate pink-striped flowers.

Boiling or roasting the tubers brings out a soft texture and a flavor often compared to sweet corn or roasted chestnut. You can also eat them raw, though they’re firmer and slightly earthy.

Mistaking it for a similar flower like star chickweed can lead to confusion, especially if you’re ignoring the root. Unlike springbeauty, those lookalikes don’t grow any edible tuber beneath them.

Skip the stems and leaves, which offer no culinary value and aren’t worth harvesting. Springbeauty’s appeal comes from its combination of subtle flavor and satisfying texture in such a tiny wild plant.

Indian Cucumber Root (Medeola virginiana)

The slender stem of Indian cucumber root grows in two tiers, with whorled leaves on each level and a delicate greenish-yellow flower hanging beneath the top whorl. Dig gently around the base and you’ll find a small, crisp white root with a refreshing cucumber-like taste.

It’s the underground rhizome that’s edible, not the above-ground parts, which lose flavor quickly after picking. Some people eat the peeled root raw on the trail, while others dice and toss it into chilled salads for a subtle crunch.

The root has a clean, watery texture, similar to a jicama stick but more tender and less fibrous. There’s no strong smell, but the mild vegetal flavor is unmistakable once you’ve tasted it.

Starflower (Trientalis borealis) grows nearby and looks similar in foliage, but it lacks the tiered leaf pattern and has no edible root. Stick to plants with both leaf whorls and dangling flowers to avoid confusion.

Chickasaw Plum (Prunus angustifolia)

Chickasaw plum, also called wild plum or Cherokee plum, grows as a low, spreading thicket with thorny branches and narrow, pointed leaves. Its fruit is small and round, turning from red to yellow as it ripens.

The tart flesh is juicy and somewhat fibrous, making it ideal for sauces or preserves. It’s especially popular in jelly making because of its high pectin content.

Although the fruit is edible, avoid chewing the seed or ingesting large amounts of it, as it contains amygdalin. It can be confused with the Mexican plum, but that one produces fruit with a more purple hue and lacks the thorny branches.

These plums have a long tradition of being used in homestead cooking and wildcraft recipes. Many foragers use them in cobblers, syrups, or even just simmered into a sweet paste.

Golden Currant (Ribes aureum)

Golden currants produce small, round berries with smooth skin and a color range that includes golden yellow, red, and deep purple. Their flavor is tangy, slightly sweet, and develops a deeper complexity when cooked down.

The berries are edible raw, but you’ll probably want to use them in syrups, sauces, or dried into snacks. Some people dehydrate them like raisins, though they’re smaller and more tart.

Leaves are palmately lobed and lightly scented, which helps set golden currants apart from potentially toxic lookalikes like some ornamental currant hybrids. Those lookalikes often lack the same strong fragrance and have less pronounced lobing on the leaves.

Don’t eat the unripe berries in large amounts, as they can be harsh on the stomach. Fermenting the juice was a traditional method of preservation among various communities, adding a unique use to its culinary profile.

Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

There are plenty of wild edibles to choose from, but some toxic native plants closely resemble them. Mistaking the wrong one can lead to severe illness or even death, so it’s important to know exactly what you’re picking.

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild carrot (Daucus carota)

Poison hemlock is a tall plant with lacy leaves and umbrella-like clusters of tiny white flowers. It has smooth, hollow stems with purple blotches and grows in sunny places like roadsides, meadows, and stream banks.

Unlike wild carrot, which has hairy stems and a dark central floret, poison hemlock has a musty odor and no flower center spot. It’s extremely toxic; just a small amount can be fatal, and even touching the sap can irritate the skin.

Water Hemlock (Cicuta spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) or wild celery (Apium spp.)

Water hemlock is a tall, branching plant with umbrella-shaped clusters of small white flowers. It grows in wet places like stream banks, marshes, and ditches, with stems that often show purple streaks or spots.

It can be confused with wild parsnip or wild celery, but its thick, hollow roots have internal chambers and release a yellow, foul-smelling sap when cut. Water hemlock is the most toxic plant in North America, and just a small amount can cause seizures, respiratory failure, and death.

False Hellebore (Veratrum viride)

Often mistaken for: Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

False hellebore is a tall plant with broad, pleated green leaves that grow in a spiral from the base, often appearing early in spring. It grows in moist woods, meadows, and along streams.

It’s commonly mistaken for ramps, but ramps have a strong onion or garlic smell, while false hellebore is odorless and later grows a tall flower stalk. The plant is highly toxic, and eating any part can cause nausea, a slowed heart rate, and even death due to its alkaloids that affect the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Death Camas (Zigadenus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild onion or wild garlic (Allium spp.)

Death camas is a slender, grass-like plant that grows from underground bulbs and is found in open woods, meadows, and grassy hillsides. It has small, cream-colored flowers in loose clusters atop a tall stalk.

It’s often confused with wild onion or wild garlic due to their similar narrow leaves and habitats, but only Allium plants have a strong onion or garlic scent, while death camas has none. The plant is extremely poisonous, especially the bulbs, and even a small amount can cause nausea, vomiting, a slowed heartbeat, and potentially fatal respiratory failure.

Buckthorn Berries (Rhamnus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Elderberries (Sambucus spp.)

Buckthorn is a shrub or small tree often found along woodland edges, roadsides, and disturbed areas. It produces small, round berries that ripen to dark purple or black and usually grow in loose clusters.

These berries are sometimes mistaken for elderberries and other wild fruits, which also grow in dark clusters, but elderberries form flat-topped clusters on reddish stems while buckthorn berries are more scattered. Buckthorn berries are unsafe to eat as they contain compounds that can cause cramping, vomiting, and diarrhea, and large amounts may lead to dehydration and serious digestive problems.

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Mayapple is a low-growing plant found in shady forests and woodland clearings. It has large, umbrella-like leaves and produces a single pale fruit hidden beneath the foliage.

The unripe fruit resembles a small green grape, causing confusion with wild grapes, which grow in woody clusters on vines. All parts of the mayapple are toxic except the fully ripe, yellow fruit, which is only safe in small amounts. Eating unripe fruit or other parts can lead to nausea, vomiting, and severe dehydration.

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Virginia creeper is a fast-growing vine found on fences, trees, and forest edges. It has five leaflets per stem and produces small, bluish-purple berries from late summer to fall.

It’s often confused with wild grapes since both are climbing vines with similar berries, but grapevines have large, lobed single leaves and tighter fruit clusters. Virginia creeper’s berries are toxic to humans and contain oxalate crystals that can cause nausea, vomiting, and throat irritation.

Castor Bean (Ricinus communis)

Often mistaken for: Wild rhubarb (Rumex spp. or Rheum spp.)

Castor bean is a bold plant with large, lobed leaves and tall red or green stalks, often found in gardens, along roadsides, and in disturbed areas in warmer regions in the US. Its red-tinged stems and overall size can resemble wild rhubarb to the untrained eye.

Unlike rhubarb, castor bean plants produce spiny seed pods containing glossy, mottled seeds that are extremely toxic. These seeds contain ricin, a deadly compound even in small amounts. While all parts of the plant are toxic, the seeds are especially dangerous and should never be handled or ingested.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

How to Get the Best Results Foraging

Safety should always come first when it comes to foraging. Whether you’re in a rural forest or a suburban greenbelt, knowing how to harvest wild foods properly is a key part of staying safe and respectful in the field.

Always Confirm Plant ID Before You Harvest Anything

Knowing exactly what you’re picking is the most important part of safe foraging. Some edible plants have nearly identical toxic lookalikes, and a wrong guess can make you seriously sick.

Use more than one reliable source to confirm your ID, like field guides, apps, and trusted websites. Pay close attention to small details. Things like leaf shape, stem texture, and how the flowers or fruits are arranged all matter.

Not All Edible Plants Are Safe to Eat Whole

Just because a plant is edible doesn’t mean every part of it is safe. Some plants have leaves, stems, or seeds that can be toxic if eaten raw or prepared the wrong way.

For example, pokeweed is only safe when young and properly cooked, while elderberries need to be heated before eating. Rhubarb stems are fine, but the leaves are poisonous. Always look up which parts are edible and how they should be handled.

Avoid Foraging in Polluted or Contaminated Areas

Where you forage matters just as much as what you pick. Plants growing near roads, buildings, or farmland might be coated in chemicals or growing in polluted soil.

Even safe plants can take in harmful substances from the air, water, or ground. Stick to clean, natural areas like forests, local parks that allow foraging, or your own yard when possible.

Don’t Harvest More Than What You Need

When you forage, take only what you plan to use. Overharvesting can hurt local plant populations and reduce future growth in that area.

Leaving plenty behind helps plants reproduce and supports wildlife that depends on them. It also ensures other foragers have a chance to enjoy the same resources.

Protect Yourself and Your Finds with Proper Foraging Gear

Having the right tools makes foraging easier and safer. Gloves protect your hands from irritants like stinging nettle, and a good knife or scissors lets you harvest cleanly without damaging the plant.

Use a basket or breathable bag to carry what you collect. Plastic bags hold too much moisture and can cause your greens to spoil before you get home.

This forager’s toolkit covers the essentials for any level of experience.

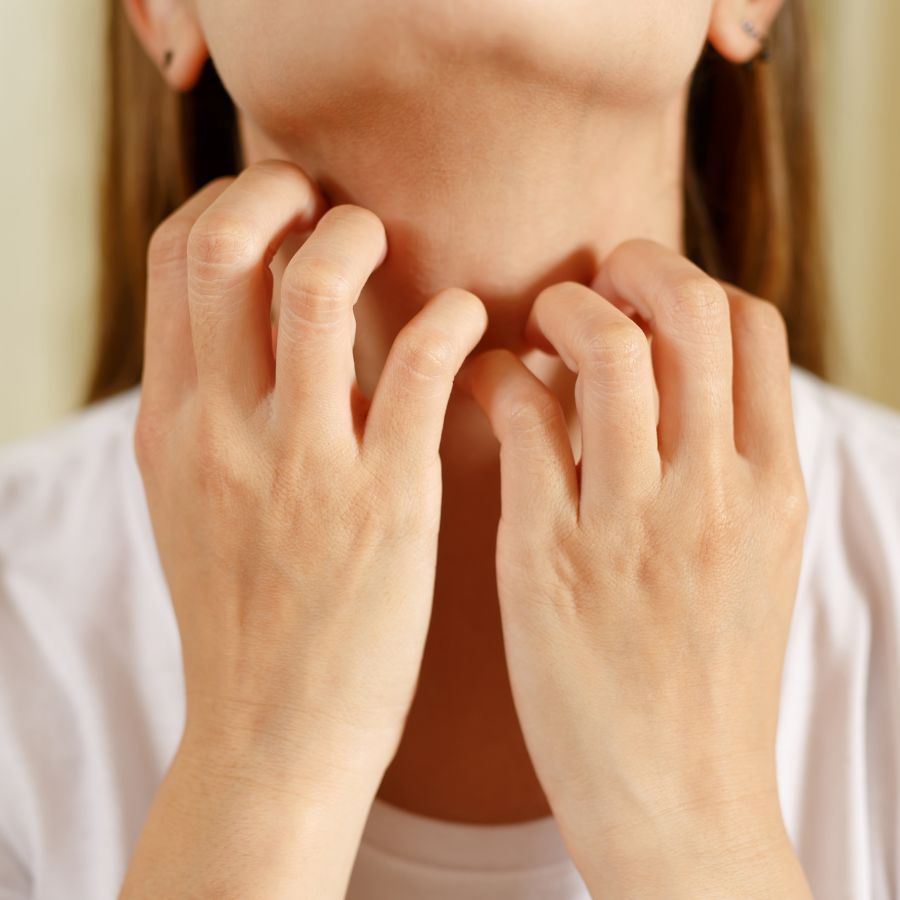

Watch for Allergic Reactions When Trying New Wild Foods

Even if a wild plant is safe to eat, your body might react to it in unexpected ways. It’s best to try a small amount first and wait to see how you feel.

Be extra careful with kids or anyone who has allergies. A plant that’s harmless for one person could cause a reaction in someone else.

Check Local Rules Before Foraging on Any Land

Before you start foraging, make sure you know the rules for the area you’re in. What’s allowed in one spot might be completely off-limits just a few miles away.

Some public lands permit limited foraging, while others, like national parks, usually don’t allow it at all. If you’re on private property, always get permission first.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

Where to Find Forageables in the State

There is a range of foraging spots where edible plants grow naturally and often in abundance:

| Plant | Locations |

| Bramble (Rubus fruticosus) | – Kisatchie National Forest – Pearl River Wildlife Management Area – Tunica Hills Wildlife Management Area |

| Muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia) | – Chicot State Park – Tickfaw State Park – Lake Claiborne State Park |

| Elderberry (Sambucus nigra) | – Cockeyed Farms, Franklinton – Bogue Chitto State Park – Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge |

| Wild Onion (Allium canadense) | – Kisatchie National Forest – Bayou Cocodrie National Wildlife Refuge – Sabine National Wildlife Refuge |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | – Fontainebleau State Park – Lake Fausse Pointe State Park – Sam Houston Jones State Park |

| Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule) | – Palmetto Island State Park – Grand Isle State Park – Bayou Segnette State Park |

| Wild Garlic (Allium vineale) | – Red River Wildlife Management Area – Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge – Sherburne Wildlife Management Area |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | – Catahoula National Wildlife Refuge – Lake Bistineau State Park – Bayou Macon Wildlife Management Area |

| American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | – Kisatchie National Forest – Chemin-A-Haut State Park – Sicily Island Hills Wildlife Management Area |

| Mulberry (Morus rubra) | – Tunica Hills Wildlife Management Area – Lake D’Arbonne State Park – Boeuf Wildlife Management Area |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | – Bayou Sauvage National Wildlife Refuge – Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve – Pearl River Wildlife Management Area |

| American Beautyberry (Callicarpa americana) | – Kisatchie National Forest – Tickfaw State Park – Lake Claiborne State Park |

| Greenbrier (Smilax bona-nox) | – Chicot State Park – Bayou Teche National Wildlife Refuge – Lake Fausse Pointe State Park |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | – Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge – Red River Wildlife Management Area – Bayou Cocodrie National Wildlife Refuge |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | – Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge – Lake Ophelia National Wildlife Refuge – Bayou Macon Wildlife Management Area |

| Tall Lettuce (Lactuca virosa) | – Kisatchie National Forest – Sabine National Wildlife Refuge – Boeuf Wildlife Management Area |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta) | – Fontainebleau State Park – Palmetto Island State Park – Lake Bistineau State Park |

| Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) | – Chicot State Park – Lake Claiborne State Park – Tunica Hills Wildlife Management Area |

| Common Blue Violet (Viola sororia) | – Tickfaw State Park – Bayou Segnette State Park – Sam Houston Jones State Park |

| Sumac (Rhus glabra) | – Kisatchie National Forest – Sicily Island Hills Wildlife Management Area – Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge |

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | – Tunica Hills Wildlife Management Area – Chemin-A-Haut State Park – Lake D’Arbonne State Park |

| Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) | – Palmetto Island State Park – Grand Isle State Park – Bayou Teche National Wildlife Refuge |

| Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) | – Lake Fausse Pointe State Park – Bayou Sauvage National Wildlife Refuge – Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | – Bayou Cocodrie National Wildlife Refuge – Red River Wildlife Management Area – Bayou Macon Wildlife Management Area |

| Burdock (Arctium minus) | – Kisatchie National Forest – Lake Claiborne State Park – Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge |

| Sow Thistle (Sonchus oleraceus) | – Kisatchie National Forest – Bayou Segnette State Park – Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge |

| Smartweed (Persicaria pensylvanica) | – Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge – Lake Fausse Pointe State Park – Pearl River Wildlife Management Area |

| Spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis) | – Chicot State Park – Tunica Hills Wildlife Management Area – Lake Claiborne State Park |

| Redbud (Cercis canadensis) | – Louisiana State Arboretum – Chemin-A-Haut State Park – Tickfaw State Park |

| Bull Thistle (Cirsium vulgare) | – Kisatchie National Forest – Boeuf Wildlife Management Area – Lake Bistineau State Park |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | – Bayou Sauvage National Wildlife Refuge – Fontainebleau State Park – Lake D’Arbonne State Park |

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | – Sabine National Wildlife Refuge – Lake Claiborne State Park – Bayou Macon Wildlife Management Area |

| Wild Bergamot (Monarda citriodora) | – Red River Wildlife Management Area – Palmetto Island State Park – Lake Fausse Pointe State Park |

| Broadleaf Arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia) | – Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge – Bayou Teche National Wildlife Refuge – Lake Fausse Pointe State Park |

| American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea) | – Catahoula National Wildlife Refuge – Lake Ophelia National Wildlife Refuge – Bayou Cocodrie National Wildlife Refuge |

| Eastern Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia humifusa) | – Tunica Hills Wildlife Management Area – Sicily Island Hills Wildlife Management Area – Kisatchie National Forest |

| Peppergrass (Lepidium virginicum) | – Bayou Macon Wildlife Management Area – Lake Bistineau State Park – Red River Wildlife Management Area |

| Shepherd’s Purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris) | – Chicot State Park – Lake Claiborne State Park – Bayou Segnette State Park |

| Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) | – Palmetto Island State Park – Grand Isle State Park – Bayou Teche National Wildlife Refuge |

| Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) | – Kisatchie National Forest – Tickfaw State Park – Lake Claiborne State Park |

| Maple (Acer rubrum) | – Chicot State Park – Lake D’Arbonne State Park – Tunica Hills Wildlife Management Area |

| Toothwort (Cardamine concatenata) | – Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge – Sicily Island Hills Wildlife Management Area – Chemin-A-Haut State Park |

| Virginia Springbeauty (Claytonia virginica) | – Lake Claiborne State Park – Tunica Hills Wildlife Management Area – Chicot State Park |

| Indian Cucumber Root (Medeola virginiana) | – Kisatchie National Forest – Tunica Hills Wildlife Management Area – Lake D’Arbonne State Park |

| Red Mulberry (Morus alba) | – Bayou Macon Wildlife Management Area – Lake Bistineau State Park – Red River Wildlife Management Area |

| Chickasaw Plum (Prunus angustifolia) | – Chicot State Park – Lake Claiborne State Park – Palmetto Island State Park |

| Golden Currant (Ribes aureum) | – Kisatchie National Forest – Lake D’Arbonne State Park – Tunica Hills Wildlife Management Area |

| River Cane (Arundinaria gigantea) | – Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge – Bayou Teche National Wildlife Refuge – Lake Fausse Pointe State Park |

| Yucca (Yucca filamentosa) | – Sicily Island Hills Wildlife Management Area – Tunica Hills Wildlife Management Area – Kisatchie National Forest |

Peak Foraging Seasons

Different edible plants grow at different times of year, depending on the season and weather. Timing your search makes all the difference.

Spring

Spring brings a fresh wave of wild edible plants as the ground thaws and new growth begins:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | February – April | Cool, moist, overcast or partly sunny days after rain |

| Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule) | February – April | Damp soil, mild temps, cloudy to partly sunny conditions |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | February – April | Cold running water, clear sunny or cloudy skies |

| Shepherd’s Purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris) | February – April | Cool, disturbed soil, after light rain or dew |

| Virginia Springbeauty (Claytonia virginica) | February – April | Cool, shady areas, best just after rain |

| Wild Onion (Allium canadense) | March – May | Cool to warm days, loose moist soil, sunny patches in woods or meadows |

| Wild Garlic (Allium vineale) | March – May | After spring rain, in grassy areas with light shade |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | March – May | Sunny to partly cloudy, recently rained or morning dew |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | March – May | Moist soil, overcast or mild sunny days, newly disturbed ground |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta) | March – May | Light shade, moist soil, following rain |

| Common Blue Violet (Viola sororia) | March – May | Damp woods or lawns, early morning after dew or light rain |

| Burdock (Arctium minus) | March – May (for roots) | Loose soil, after rain, mild daytime temps |

| Greenbrier (Smilax bona-nox) | March – May (young shoots) | After spring rain, in wooded thickets and edges |

| Sow Thistle (Sonchus oleraceus) | March – May | Cool, moist weather; overcast or after light rain |

| Spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis) | March – May | Mild temps, light morning dew, partial sun |

| Redbud (Cercis canadensis) | March – April | Sunny days with moderate temperatures, dry ground |

| Toothwort (Cardamine concatenata) | March – April | Damp forest floors, mild days, morning dew |

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | March – May | Sunny days, well-drained soils, mild temps |

| Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) | April – May (young shoots) | Warm days, sunny, sandy or loamy soil |

| Tall Lettuce (Lactuca virosa) | April – May | Sunny days, rich woodland soil, moderate temps |

| Sumac (Rhus glabra) | April – May (young shoots) | Warm, sunny days in open areas |

| Smartweed (Persicaria pensylvanica) | April – May | Warm, wet conditions near wetlands or ditches |

| Bull Thistle (Cirsium vulgare) | April – May (young leaves) | Cool, moist conditions, especially after rain |

| Wild Bergamot (Monarda citriodora) | April – May | Warm sunny days, low humidity, open woodlands |

| Broadleaf Arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia) | April – May | Shallow freshwater areas, mild temps, after rain |

| Indian Cucumber Root (Medeola virginiana) | March – May | Moist, shaded woods, overcast days or early morning |

Summer

Summer is a peak season for foraging, with fruits, flowers, and greens growing in full force:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Bramble (Rubus fruticosus) | May – July | Sunny to partly cloudy, early morning for ripe berries |

| Mulberry (Morus rubra) | May – June | Warm weather, dry days, harvest early morning |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | May – July | Warm, dry weather, near disturbed soils or field edges |

| Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) | May – July | Sunny mornings, dry days, well-drained acidic soil |

| Red Mulberry (Morus alba) | May – June | Warm, dry weather, early morning harvesting |

| Chickasaw Plum (Prunus angustifolia) | May – July | Hot days, dry areas near thickets or open woods |

| Golden Currant (Ribes aureum) | June – July | Warm, low humidity, sunny forest edges |

| Elderberry (Sambucus nigra) | June – August | Warm and sunny, early morning for berries before heat |

| Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) | June – August | Sunny weather, dry ground, bloom in full sun |

| Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) | June – August (flowers/pods) | Full sun, dry to moist open areas |

| Smartweed (Persicaria pensylvanica) | June – August | Wet, sunny to partly cloudy days, near water |

| Bull Thistle (Cirsium vulgare) | June – July (flowers) | Hot days, dry fields or disturbed areas |

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | June – August | Hot, dry weather, well-drained meadows |

| Wild Bergamot (Monarda citriodora) | June – August | Full sun, low humidity, open fields |

| Broadleaf Arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia) | June – August | Warm, wet days in shallow, slow-moving water |

| Eastern Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia humifusa) | June – August | Hot, dry conditions, sandy or rocky soil |

| Peppergrass (Lepidium virginicum) | June – August | Dry soil, full sun, best after early morning dew |

| Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) | June – August | Sunny, warm weather with good drainage |

| Muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia) | July – September | Hot days, full sun, dry conditions for sweetest fruit |

| American Beautyberry (Callicarpa americana) | July – September | Hot, humid conditions, often near woodland edges |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | July – September (pods) | Warm, wet conditions near stream banks |

| American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea) | July – September | Hot, sunny weather, in calm shallow water |

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | August – September | Hot days, shady riparian zones, best in humid weather |

| Sumac (Rhus glabra) | August – September (berries) | Hot and dry days, open spaces |

| Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) | August – September | Hot, sunny days, well-drained soils |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | August – September (flowers) | Warm and sunny, well-drained soil |

Fall

As temperatures drop, many edible plants shift underground or produce their last harvests:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | September | Warm but waning days, under forest canopy |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | September (late seeds) | Dry and cool, especially around disturbed land |

| Bull Thistle (Cirsium vulgare) | September (seed heads) | Dry and sunny, low competition areas |

| American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea) | September (seeds/rhizomes) | Warm, sunny days in shallow still waters |

| Red Mulberry (Morus alba) | September (late season) | Warm days, early morning in shaded edges |

| Chickasaw Plum (Prunus angustifolia) | September (late fruits) | Dry and sunny, thinning thickets or field edges |

| Golden Currant (Ribes aureum) | September (late fruits) | Cool, dry days, edge habitats and wood margins |

| Sumac (Rhus glabra) | September – October (berries) | Dry weather, collect before heavy rain washes flavor |

| Smartweed (Persicaria pensylvanica) | September – October | Wet conditions, warm afternoons, lowland areas |

| Broadleaf Arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia) | September – October | Moist wetland margins, early morning |

| Peppergrass (Lepidium virginicum) | September – October | Cool, dry air, open sunny disturbed areas |

| American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | September – November | Cool mornings, full sun, after first frost for sweetest fruit |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | September – November (tubers) | Moist soil after rain, along streambanks or low woods |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | September – November | Cool weather, moist soils in sunny clearings |

| Burdock (Arctium minus) | September – November | Loose moist soils, cool weather, roots dig best after frost |

| Sow Thistle (Sonchus oleraceus) | September – November | Cool mornings, mild sunny days, moist soil |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | October – November (tubers) | Cool days after frost, dig after tops die back |

| Shepherd’s Purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris) | October – November | Moist ground after early fall rains |

| River Cane (Arundinaria gigantea) | October – November | Cool days, near swamps or riverbanks, moist air |

| Yucca (Yucca filamentosa) | September – November | Dry, open pine woods, cool clear days |

Winter

Winter foraging is limited but still possible, with hardy plants and preserved growth holding on through the cold:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Wild Onion (Allium canadense) | December – February | Cool to cold weather, moist ground, partial sun |

| Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule) | December – February | Cold but not frozen, damp soil, cloudy or overcast days |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | December – February | Cold weather with ample moisture, best after light rain |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | December – February | Sunny winter days, after rain or during dew |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta) | December – February | Mild, wet winter days, partially shaded areas |

| Sow Thistle (Sonchus oleraceus) | December – February | Mild winter days, moist disturbed soil |

| Shepherd’s Purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris) | December – February | Cold but not frozen, damp soil |

| River Cane (Arundinaria gigantea) | December – February | Humid, mild winter conditions near creeks |

| Yucca (Yucca filamentosa) | December – February | Dry, cold-hardy environment, open sandy areas |

| Maple (Acer rubrum) | January – February (sap) | Cold nights, warm days for sap flow |

| Common Blue Violet (Viola sororia) | January – February | Cool, moist days, especially in wooded edges |

| Greenbrier (Smilax bona-nox) | January – February (young winter tips) | Damp soil, mild days, edge of woods |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | January – February | Cool moist soil, after rain, partial sun |

| Peppergrass (Lepidium virginicum) | January – February | Cool temps, dry air, after light rain |

| Tall Lettuce (Lactuca virosa) | February | Sunny days, dormant leaf rosettes in rich soil |

| Redbud (Cercis canadensis) | February (buds form) | Clear days, just before spring warmth |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.