You’d be surprised how many edible plants grow right under our noses, often unnoticed. And when you finally identify, gather, and taste something from the wild, there’s a unique satisfaction that no grocery store can match.

Kentucky’s diverse growing zones create perfect conditions for many edible wild plants. Some grow along creek beds while others thrive in open fields. The changing seasons bring different foraging opportunities throughout the year.

Before you start collecting, it’s important to learn proper plant identification. Some edible plants look similar to poisonous ones. A good field guide and practice will help you forage safely and confidently.

Let’s explore what tasty wild foods Kentucky has to offer. From spring mushrooms to summer berries and fall nuts, nature provides a full menu for those who know where to look.

What We Cover In This Article:

- The Edible Plants Found in the State

- Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

- How to Get the Best Results Foraging

- Where to Find Forageables in the State

- Peak Foraging Seasons

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

The Edible Plants Found in the State

Wild plants found across the state can add fresh, seasonal ingredients to your meals:

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba)

The pawpaw grows fruits that are green and shaped a little like small mangoes. Inside, the soft yellow flesh tastes like a blend of banana, mango, and melon, with a custard-like texture that melts in your mouth.

If you are comparing it to similar plants, keep in mind that young pawpaw trees can look a little like young magnolias because of their large leaves. True pawpaws grow fruits with large brown seeds tucked inside, while magnolias do not produce anything that looks or tastes similar.

You can eat the flesh straight out of the skin with a spoon, or mash it into puddings, smoothies, and even homemade ice cream. Some people also like to freeze it into cubes for later, although it does tend to brown quickly once exposed to air.

Stick to eating the soft inner flesh. Make sure not to ingest the skin and seeds of the fruit because they contain compounds that can upset your stomach.

This fruit is that it was a favorite snack of Native Americans and early explorers long before it started showing up in backyard gardens.

Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus)

Blackberries rank among the most rewarding wild foods to gather. These dark purple-black berries grow on thorny brambles that form thick patches in many environments. The berries are actually clusters of tiny fruits called drupelets, each containing a small seed.

Look for shrubs with arching canes covered in sharp thorns. The leaves grow in sets of three to five with toothed edges. White flowers with five petals appear in spring before developing into green berries that turn red, then black when fully ripe.

The entire berry is edible. You can eat them fresh or make them into jams, pies, and syrups. Blackberries contain high levels of vitamin C, fiber, and antioxidants that help keep you healthy.

Many people confuse blackberries with black raspberries. The key difference is that blackberries keep their core when picked, while raspberries come off hollow.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

Bright yellow flowers and jagged, deeply toothed leaves make dandelions easy to spot in open fields, lawns, and roadsides. You might also hear them called lion’s tooth, blowball, or puffball once the flowers turn into round, white seed heads.

Every part of the dandelion is edible, but you will want to avoid harvesting from places treated with pesticides or roadside areas with heavy car traffic. Besides being a food source, dandelions have been used traditionally for simple herbal remedies and natural dye projects.

Young dandelion leaves have a slightly bitter, peppery flavor that works well in salads or sautés, and the flowers can be fried into fritters or brewed into tea. Some people even roast the roots to make a coffee substitute with a rich, earthy taste.

One thing to watch out for is cat’s ear, a common lookalike with hairy leaves and branching flower stems instead of a single, hollow one. To make sure you have a true dandelion, check for a smooth, hairless stem that oozes a milky sap when broken.

Wild Leeks (Allium tricoccum)

Known as wild leek, ramp, or ramson, this flavorful plant is famous for its broad green leaves and slender white stems. It grows low to the ground and gives off a strong onion-like scent when bruised, which can help you tell it apart from toxic lookalikes like lily of the valley.

If you give it a taste, you will notice a bold mix of onion and garlic flavors, with a tender texture that softens even more when cooked. People often sauté the leaves and stems, pickle the bulbs, or blend them into pestos and soups.

The entire plant can be used for cooking, but the leaves and bulbs are the most prized parts. It is important not to confuse it with similar-looking plants that do not have the signature onion smell when crushed.

Wild leek populations have declined in some areas because of overharvesting, so it is a good idea to only take a few from any given patch. When harvested thoughtfully, these vibrant greens can add a punch of flavor to just about anything you make.

Eastern Black Walnut (Juglans nigra)

The nuts of the black walnut, sometimes called American walnut or eastern black walnut, have a tough outer husk and a deeply ridged shell inside. When you crack them open, you will find a rich, oily seed with an earthy, slightly bitter flavor that sets them apart from the sweeter English walnut.

It is easy to confuse black walnut with butternut, another tree with compound leaves and rough bark. If you check the nuts closely, black walnut fruits are round with a thick green husk, while butternuts are more oval and sticky.

When you get your hands on the nuts, the common ways to prepare them include baking them into cookies, sprinkling them over salads, or grinding them into a strong-tasting flour. The seeds themselves have a firm, almost chewy texture when raw and become crunchy after roasting.

Only the inner seed is eaten, while the outer husk and shell are discarded because they contain compounds that can irritate your skin. A fun fact about this plant is that even the roots and leaves produce a chemical called juglone, which can make it hard for other plants to grow nearby.

American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)

Persimmon, sometimes called American persimmon or common persimmon, grows as a small tree with rough, blocky bark and oval-shaped leaves. The fruit looks like a small, flattened tomato and turns a deep orange or reddish color when ripe.

If you bite into an unripe persimmon, you will quickly notice an extremely astringent, mouth-drying effect. A ripe persimmon, on the other hand, tastes sweet, rich, and custard-like, with a soft and jelly-like texture inside.

You can eat persimmons fresh once they are fully ripe, or you can cook them down into puddings, jams, and baked goods. Some people also mash and freeze the pulp to use later for pies, breads, and sauces.

Wild persimmons can sometimes be confused with black nightshade berries, but nightshade fruits are much smaller, grow in clusters, and stay dark purple or black. Only the ripe fruit of the persimmon tree should be eaten; the seeds and the unripe fruit are not edible.

Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

Garlic mustard, sometimes called poor man’s mustard or hedge garlic, has heart-shaped leaves with scalloped edges and small white four-petaled flowers. When you crush the leaves between your fingers, they release a strong garlic-like smell that makes it stand out from similar-looking plants.

The flavor of garlic mustard is sharp and garlicky at first bite, with a peppery bitterness that lingers. Its young leaves are often blended into pestos, stirred into soups, or tossed into salads to add a punch of flavor.

You can also use the roots, which have a taste similar to horseradish when fresh. The seed pods are sometimes collected and used as a spicy seasoning after being dried and crushed.

If you decide to gather some, make sure not to confuse it with plants like ground ivy or purple deadnettle, which do not have that garlic aroma. Stick to harvesting the leaves, flowers, seeds, and roots, and avoid anything with a fuzzy texture or a very different smell.

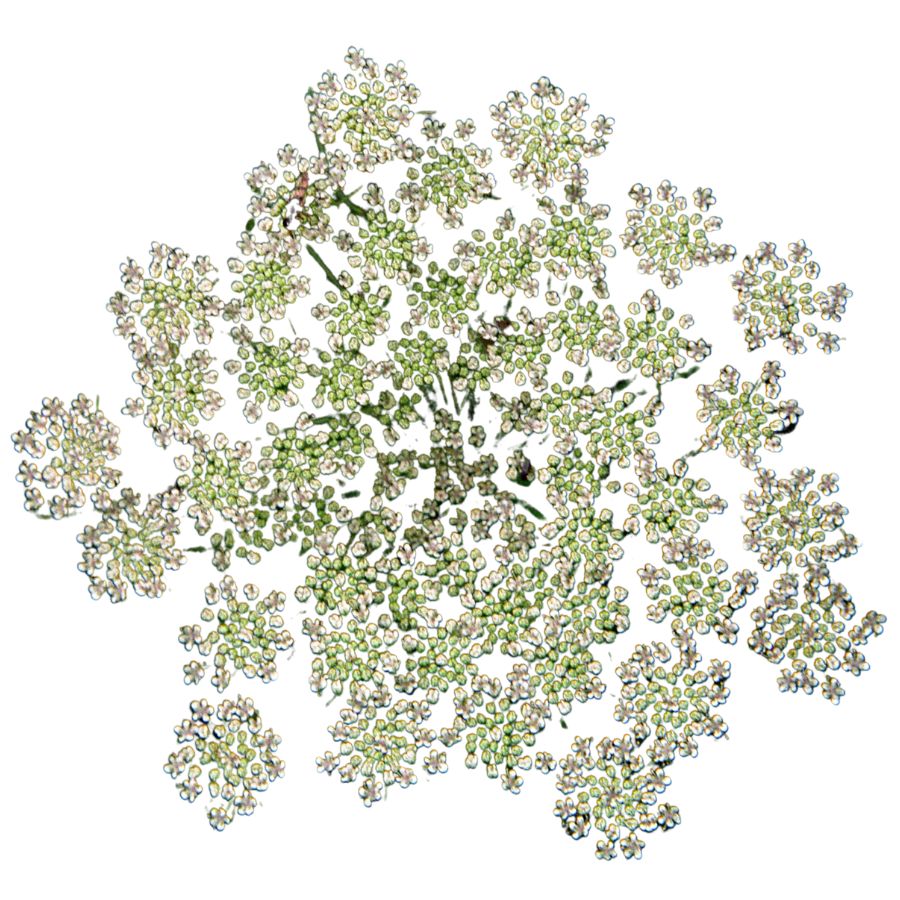

Strawberry Blite (Blitum capitatum)

One glance at the bright red clusters of Strawberry Blite makes most foragers stop in their tracks. Despite looking like tiny berries, these red clusters are not true fruits but fleshy seed coverings. They belong to the same plant family as quinoa and spinach.

Both the young leaves and seed clusters can be eaten. The leaves taste similar to spinach and can be cooked the same way. The red seed clusters have little flavor but add striking color to salads.

This plant grows one to two feet tall with triangle-shaped, toothed leaves. It produces small green flowers that develop into the eye-catching red seed clusters by mid-summer.

Strawberry Blite contains nutrients similar to its quinoa relatives. Make sure you identify it correctly, as some related plants can upset your stomach if you eat too much of them.

Wild Hyacinth (Camassia scilloides)

Long before grocery stores existed, Native American tribes relied on Wild Hyacinth bulbs as an important food source. These starchy bulbs, similar in shape to onions, grow underground beneath striking spikes of pale blue to white star-shaped flowers.

The only edible part is the bulb, which must be thoroughly cooked. Raw bulbs can cause serious stomach problems. When properly prepared through slow cooking, the bulbs offer a sweet, nutty flavor somewhat like sweet potatoes.

Several dangerous plants look similar when not in bloom, including death camas. Always check for the blue flower spikes before harvesting any bulbs. Since taking the bulb kills the plant, only collect from large patches.

Wild Hyacinth bulbs were so valuable that Native American groups traded them. They provide energy-rich carbohydrates and were traditionally pit-roasted for days to make them digestible.

Violet Wood Sorrel (Oxalis violacea)

Violet Wood Sorrel’s clover-like leaves fold downward at night or when touched. Above these leaves rise delicate purple flowers with five petals each.

The plant contains oxalic acid, which gives it the tart flavor. All above-ground parts can be eaten in small amounts. The leaves, flowers, and young seed pods add a zingy flavor to salads or can be used to make refreshing drinks.

Violet Wood Sorrel grows in small patches in woodlands and partially shaded areas. Unlike true clovers, wood sorrel leaves have heart-shaped leaflets rather than oval ones.

People with kidney disorders or gout should limit how much they eat because of the oxalic acid. Traditionally, hikers used this plant to quench thirst and add tartness to bland foods.

Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva)

Bright orange flowers known as daylily, tiger lily, or ditch lily can sometimes be mistaken for other plants that are not safe to eat. True daylilies have long, blade-like leaves that grow in clumps at the base and a hollow flower stem, while their toxic lookalikes often have solid stems or different leaf patterns.

When it comes to flavor, daylily buds have a crisp texture and a mild taste that some people compare to green beans or asparagus. The flowers are tender and slightly sweet, which makes them popular for tossing into salads or lightly stir-frying.

Most people use the unopened flower buds in cooking, but the young shoots and tuber-like roots are also gathered for food. Always make sure you are harvesting from clean areas, because roadside plants can carry pollutants that are not safe to eat.

A few important cautions come with daylilies, since some people experience digestive upset after eating large amounts. Start by tasting a small quantity first to see how your body reacts before eating more.

Curly Dock (Rumex crispus)

Curly dock, sometimes called yellow dock, is easy to spot once you know what to look for. It has long, wavy-edged leaves that form a rosette at the base, with tall stalks that eventually turn rusty brown as seeds mature.

The young leaves are edible and often cooked to mellow out their sharp, lemony taste, which can be too strong when eaten raw. You can also dry and powder the seeds to use as a flour supplement, although they are tiny and take some effort to prepare.

Curly dock has some lookalikes, like other types of dock and sorrel, but its heavily crinkled leaf edges and thick taproot help it stand out. Be careful not to confuse it with plants like wild rhubarb, which can have toxic parts if misidentified.

Besides being edible, curly dock has a history of being used in homemade remedies for skin irritation. The roots are not eaten raw because they are tough and contain compounds that can upset your stomach if you are not careful.

Toothwort (Cardamine concatenata)

Toothwort, often referred to as pepperroot or crinkleroot, has ragged-edged basal leaves and a string of knobby white rhizomes underground that look like a broken necklace. The rhizomes deliver a pungent flavor somewhere between mustard and horseradish, with a satisfying crunch.

Some people mistake it for cutleaf toothwort, which is also edible, but the more deeply lobed leaves and less spicy root can help you distinguish the two. A bigger concern is confusing it with young hellebore shoots, which lack the segmented roots and are toxic.

The roots can be eaten raw or lightly cooked and are especially good grated into vinegar-based slaws or added to mustards. If you’re fermenting vegetables, adding shaved crinkleroot gives the mix a lively heat.

Leaves and flowers are edible but lack the punch of the rhizome and tend to wilt quickly, making them less useful. You don’t need to cook the root, but heating it slightly can mellow the bite without losing the flavor.

Common Mallow (Malva neglecta)

Mallow, often called common mallow or cheeseweed, grows low to the ground and spreads with round, crinkled leaves that look a bit like tiny lily pads. It produces small pale purple or pink flowers with five delicate petals, and the seed pods are shaped like little green wheels.

The leaves, flowers, and immature seed pods of mallow are all edible, offering a mild, slightly sweet flavor and a soft, somewhat mucilaginous texture. Some people add the leaves to salads, toss them into soups for thickening, or quickly sauté them with garlic for a simple side dish.

When gathering mallow, make sure you do not confuse it with young deadly nightshade plants, which can sometimes grow in similar weedy areas but have very different flower and fruit structures. Mallow is safe to eat, but it tends to absorb pollutants from the soil, so be cautious about harvesting from roadsides or contaminated areas.

An interesting thing about mallow is that it was traditionally used for soothing sore throats and irritated skin because of its natural slimy quality. If you are foraging for food and medicine, mallow is a versatile and easy plant to start with once you are confident in your identification.

Garlic Chives (Allium tuberosum)

Garlic chives grow in grassy clumps with flat, linear leaves that rise up to 20 inches tall. The leaves give off a distinct garlic aroma when crushed, making them easy to identify by smell alone. Their star-shaped white flowers appear in late summer, attracting various pollinators to the garden.

Unlike regular chives, these plants have a stronger garlic flavor rather than an onion taste. The entire plant is edible, though most foragers harvest the leaves and flowers. They make excellent additions to stir-fries, soups, and salads.

Look for the flat leaves to distinguish them from regular chives, which have hollow, round leaves. Wild onion can look similar but lacks the strong garlic scent. Garlic chives provide vitamin C, calcium, and iron, making them both tasty and nutritious additions to meals.

Redbud (Cercis canadensis)

The small, pinkish-purple flowers of the eastern redbud grow directly from the branches and even the trunk. These blooms are edible raw and have a slightly tangy, pea-like flavor that works well in salads or as a garnish.

You can also eat the young seed pods when they’re still flat and tender. They taste somewhat like snow peas and can be lightly steamed, stir-fried, or pickled.

Avoid older seed pods, which become tough and fibrous. Also be aware that while the flowers and young pods are safe to eat, the mature seeds and bark are not consumed.

Some people sprinkle the blossoms into baked goods for a splash of color and a mild floral note. Others like to candy the flowers, though they lose some of their fresh bite in the process.

Endive (Cichorium endivia)

Endive displays curly, deeply cut leaves arranged in a loose rosette pattern. Its slightly bitter taste becomes milder when blanched by covering the plant to block sunlight during growth. The outer leaves appear green while the inner leaves show pale yellow to white coloration.

Identifying endive is straightforward, as its distinctive curly or broad leaves differ from other leafy greens.

The entire plant is edible, though most people prefer the leaves. Wild chicory looks similar but has more deeply toothed leaves and blue flowers.

Endive contains valuable nutrients including folate, vitamins A and K. The slight bitterness comes from compounds that aid digestion. Foragers appreciate endive for salads, where its crisp texture and pleasantly bitter flavor balance sweeter ingredients. The leaves can also be sautéed or added to soups for extra nutrition and flavor.

Wild Lettuce (Lactuca virosa)

Wild lettuce jagged leaves with spines along the center vein release a milky sap when broken. This plant earned the nickname “lettuce opium” for its mild sedative properties in traditional herbal medicine.

The young leaves are edible when harvested before the plant flowers and becomes too bitter. The milky sap helps identify wild lettuce, though it can cause skin irritation in sensitive individuals.

Be careful not to confuse it with prickly lettuce, which looks similar but has more pronounced spines.

Wild lettuce has been used for centuries as a natural sleep aid and mild pain reliever. Foragers typically collect young leaves for salads or cooked dishes, avoiding the bitter older leaves that develop as the plant matures.

Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

Wild bergamot has clusters of lavender-colored flowers and opposite leaves that smell like thyme when crushed. Its flavor leans herbal and minty, with a little bitterness that works well in marinades.

The flower heads are shaggy and irregular, and the plant’s square stem helps tell it apart from lookalikes like spotted horsemint.

In recipes, it’s most often dried and steeped or blended into herb mixes.

Both leaves and petals can be eaten, though most people avoid the stems. Don’t eat it in large amounts raw—it’s strong and can be overpowering.

It’s related to mint, and that shows in how fast the flavor develops when heat is applied. You’ll get the most aroma if you bruise the leaves before using them.

Sweet Acorn Oak (Quercus rotundifolia)

Rounded, evergreen leaves with smooth edges characterize the sweet acorn oak tree, which produces unusually sweet acorns requiring minimal processing.

The acorns grow to about one inch long with a distinctive cap covering about one-third of the nut. Native to Mediterranean regions, these trees can live for centuries.

The acorns contain less tannic acid than other oak species, making them less bitter and easier to prepare. To use them, remove the caps and shells, then grind the nuts into flour for baking or roast them for a nutritious snack.

Foragers value these acorns for their high content of healthy fats, protein, and carbohydrates. Indigenous people worldwide have relied on acorns as a staple food source for thousands of years.

Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

There are plenty of wild edibles to choose from, but some toxic native plants closely resemble them. Mistaking the wrong one can lead to severe illness or even death, so it’s important to know exactly what you’re picking.

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild carrot (Daucus carota)

Poison hemlock is a tall plant with lacy leaves and umbrella-like clusters of tiny white flowers. It has smooth, hollow stems with purple blotches and grows in sunny places like roadsides, meadows, and stream banks.

Unlike wild carrot, which has hairy stems and a dark central floret, poison hemlock has a musty odor and no flower center spot. It’s extremely toxic; just a small amount can be fatal, and even touching the sap can irritate the skin.

Water Hemlock (Cicuta spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) or wild celery (Apium spp.)

Water hemlock is a tall, branching plant with umbrella-shaped clusters of small white flowers. It grows in wet places like stream banks, marshes, and ditches, with stems that often show purple streaks or spots.

It can be confused with wild parsnip or wild celery, but its thick, hollow roots have internal chambers and release a yellow, foul-smelling sap when cut. Water hemlock is the most toxic plant in North America, and just a small amount can cause seizures, respiratory failure, and death.

False Hellebore (Veratrum viride)

Often mistaken for: Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

False hellebore is a tall plant with broad, pleated green leaves that grow in a spiral from the base, often appearing early in spring. It grows in moist woods, meadows, and along streams.

It’s commonly mistaken for ramps, but ramps have a strong onion or garlic smell, while false hellebore is odorless and later grows a tall flower stalk. The plant is highly toxic, and eating any part can cause nausea, a slowed heart rate, and even death due to its alkaloids that affect the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Death Camas (Zigadenus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild onion or wild garlic (Allium spp.)

Death camas is a slender, grass-like plant that grows from underground bulbs and is found in open woods, meadows, and grassy hillsides. It has small, cream-colored flowers in loose clusters atop a tall stalk.

It’s often confused with wild onion or wild garlic due to their similar narrow leaves and habitats, but only Allium plants have a strong onion or garlic scent, while death camas has none. The plant is extremely poisonous, especially the bulbs, and even a small amount can cause nausea, vomiting, a slowed heartbeat, and potentially fatal respiratory failure.

Buckthorn Berries (Rhamnus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Elderberries (Sambucus spp.)

Buckthorn is a shrub or small tree often found along woodland edges, roadsides, and disturbed areas. It produces small, round berries that ripen to dark purple or black and usually grow in loose clusters.

These berries are sometimes mistaken for elderberries and other wild fruits, which also grow in dark clusters, but elderberries form flat-topped clusters on reddish stems while buckthorn berries are more scattered. Buckthorn berries are unsafe to eat as they contain compounds that can cause cramping, vomiting, and diarrhea, and large amounts may lead to dehydration and serious digestive problems.

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Mayapple is a low-growing plant found in shady forests and woodland clearings. It has large, umbrella-like leaves and produces a single pale fruit hidden beneath the foliage.

The unripe fruit resembles a small green grape, causing confusion with wild grapes, which grow in woody clusters on vines. All parts of the mayapple are toxic except the fully ripe, yellow fruit, which is only safe in small amounts. Eating unripe fruit or other parts can lead to nausea, vomiting, and severe dehydration.

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Virginia creeper is a fast-growing vine found on fences, trees, and forest edges. It has five leaflets per stem and produces small, bluish-purple berries from late summer to fall.

It’s often confused with wild grapes since both are climbing vines with similar berries, but grapevines have large, lobed single leaves and tighter fruit clusters. Virginia creeper’s berries are toxic to humans and contain oxalate crystals that can cause nausea, vomiting, and throat irritation.

Castor Bean (Ricinus communis)

Often mistaken for: Wild rhubarb (Rumex spp. or Rheum spp.)

Castor bean is a bold plant with large, lobed leaves and tall red or green stalks, often found in gardens, along roadsides, and in disturbed areas in warmer regions in the US. Its red-tinged stems and overall size can resemble wild rhubarb to the untrained eye.

Unlike rhubarb, castor bean plants produce spiny seed pods containing glossy, mottled seeds that are extremely toxic. These seeds contain ricin, a deadly compound even in small amounts. While all parts of the plant are toxic, the seeds are especially dangerous and should never be handled or ingested.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

How to Get the Best Results Foraging

Safety should always come first when it comes to foraging. Whether you’re in a rural forest or a suburban greenbelt, knowing how to harvest wild foods properly is a key part of staying safe and respectful in the field.

Always Confirm Plant ID Before You Harvest Anything

Knowing exactly what you’re picking is the most important part of safe foraging. Some edible plants have nearly identical toxic lookalikes, and a wrong guess can make you seriously sick.

Use more than one reliable source to confirm your ID, like field guides, apps, and trusted websites. Pay close attention to small details. Things like leaf shape, stem texture, and how the flowers or fruits are arranged all matter.

Not All Edible Plants Are Safe to Eat Whole

Just because a plant is edible doesn’t mean every part of it is safe. Some plants have leaves, stems, or seeds that can be toxic if eaten raw or prepared the wrong way.

For example, pokeweed is only safe when young and properly cooked, while elderberries need to be heated before eating. Rhubarb stems are fine, but the leaves are poisonous. Always look up which parts are edible and how they should be handled.

Avoid Foraging in Polluted or Contaminated Areas

Where you forage matters just as much as what you pick. Plants growing near roads, buildings, or farmland might be coated in chemicals or growing in polluted soil.

Even safe plants can take in harmful substances from the air, water, or ground. Stick to clean, natural areas like forests, local parks that allow foraging, or your own yard when possible.

Don’t Harvest More Than What You Need

When you forage, take only what you plan to use. Overharvesting can hurt local plant populations and reduce future growth in that area.

Leaving plenty behind helps plants reproduce and supports wildlife that depends on them. It also ensures other foragers have a chance to enjoy the same resources.

Protect Yourself and Your Finds with Proper Foraging Gear

Having the right tools makes foraging easier and safer. Gloves protect your hands from irritants like stinging nettle, and a good knife or scissors lets you harvest cleanly without damaging the plant.

Use a basket or breathable bag to carry what you collect. Plastic bags hold too much moisture and can cause your greens to spoil before you get home.

This forager’s toolkit covers the essentials for any level of experience.

Watch for Allergic Reactions When Trying New Wild Foods

Even if a wild plant is safe to eat, your body might react to it in unexpected ways. It’s best to try a small amount first and wait to see how you feel.

Be extra careful with kids or anyone who has allergies. A plant that’s harmless for one person could cause a reaction in someone else.

Check Local Rules Before Foraging on Any Land

Before you start foraging, make sure you know the rules for the area you’re in. What’s allowed in one spot might be completely off-limits just a few miles away.

Some public lands permit limited foraging, while others, like national parks, usually don’t allow it at all. If you’re on private property, always get permission first.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

Where to Find Forageables in the State

There is a range of foraging spots where edible plants grow naturally and often in abundance:

| Plant | Locations |

|---|---|

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | – Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest – Red River Gorge woodlands – Jefferson Memorial Forest |

| Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus) | – Otter Creek Outdoor Recreation Area – Raven Run Nature Sanctuary – Land Between the Lakes area |

| Common Dewberry (Rubus flagellaris) | – Taylorsville Lake State Park – Green River State Forest – Carter Caves State Resort Park |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | – Idlewild Park meadows – Veterans Park fields – Western Kentucky University campus lawns |

| Garden Sage (Salvia officinalis) | – Jackson’s Orchard herb garden – Yew Dell Botanical Gardens – UK Arboretum herb beds |

| Saskatoon (Amelanchier alnifolia) | – Berea College Forest – Knobs State Forest – Daniel Boone Forest edges |

| White Mulberry (Morus alba) | – Along Elkhorn Creek – Panbowl Lake shoreline – Rotary Park in Hopkinsville |

| American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | – Boone County Arboretum – Nolin River Lake area – Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill |

| Wild Leeks (Allium tricoccum) | – Pine Mountain State Resort Park – Natural Bridge State Resort Park – Cumberland Gap area |

| Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus) | – Cumberland Falls State Resort Park – Laurel River Lake shoreline – Kingdom Come State Park |

| Allegheny Blackberry (Rubus allegheniensis) | – Pennyrile Forest State Resort Park – John James Audubon State Park – Greenbo Lake State Resort Park |

| Prairie Crab Apple (Malus ioensis) | – Big Bone Lick Historic Site – Big South Fork Scenic trails (KY side) – Jackson’s Orchard gardens |

| Sweet Acorn Oak (Quercus rotundifolia) | – McConnell Springs Park – Otter Pond Wildlife Management Area – Falls of Rough forest border |

| Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | – E.P. Tom Sawyer State Park – Ballard Wildlife Management Area – Ben Hawes Park woodlands |

| Wild Chives (Allium schoenoprasum) | – Camp Currie woodlands – Benjy Kinman Lake paths – Green River State Forest |

| Wild Garlic (Allium vineale) | – Idlewild Park fields – Veterans Park meadows – Western Kentucky University campus grounds |

| Chicory (Cichorium intybus) | – Along US Route 60 near Versailles – Roadside edges near Murray – Fields near Morehead |

| Ramsons (Allium ursinum) | – Fagan Branch Reservoir woods – Metropolis Lake State Nature Preserve – Goochland Cave trails |

| Garlic Chives (Allium tuberosum) | – Grassy Creek Nature Preserve – Givens WMA grasslands – Knobs State Nature Preserve |

| Endive (Cichorium endivia) | – Community gardens in Lexington – Urban gardens in Louisville – Community plots in Bowling Green |

| Eastern Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | – Along Kentucky River near Frankfort – Lake Reba Recreational Complex – Givens WMA grasslands |

| Black Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) | – Cave Run Lake trails – Peabody Wildlife Management Area – John A. Kleber WMA |

| Redbud (Cercis canadensis) | – Camp Webb near Grayson – Martins Fork Wildlife Management Area – Grayson Lake backwoods |

| Toothwort (Cardamine spp.) | – Cane Creek Wildlife Management Area – Higginson-Henry WMA – Lake Malone State Park |

| Common Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) | – Reed Creek bottomlands – Yellowbank Wildlife Management Area – Banklick Woods in Erlanger |

| Wild Hyacinth (Camassia scilloides) | – Red River Gorge meadows – Berea College Forest clearings – Lake Beshear shoreline |

| Wild Sweet Potato (Ipomoea pandurata) | – Roadside edges near Mayfield – Fields near Morehead – Along US Route 60 near Versailles |

| Wild Lettuce (Lactuca virosa) | – Otter Pond Wildlife Management Area – Lake Malone State Park – E.P. Tom Sawyer State Park |

| Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) | – Big Reedy Creek area – McConnell Springs Park – Ballard Wildlife Management Area |

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | – Reed Creek bottomlands – Lake Reba Recreational Complex – Fagan Branch Reservoir woods |

| Strawberry Blite (Blitum capitatum) | – Lake Beshear shoreline – Greenbo Lake dam area – Peabody Wildlife Management Area |

| Violet Wood Sorrel (Oxalis violacea) | – Lake Reba Recreational Complex – Givens WMA grasslands – John A. Kleber WMA |

| Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) | – Grassy Creek Nature Preserve – Goochland Cave trails – Metropolis Lake State Nature Preserve |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | – Along US Route 60 near Versailles – Roadside edges near Murray – Fields near Morehead |

| Sheep Sorrel (Rumex acetosella) | – Idlewild Park meadows – Veterans Park fields – Western Kentucky University campus lawns |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | – Community gardens in Lexington – Urban gardens in Louisville – Community plots in Bowling Green |

| Common Mallow (Malva neglecta) | – Along Elkhorn Creek – Abandoned fields near Mayfield – Roadside thickets near Ashland |

Peak Foraging Seasons

Different edible plants grow at different times of year, depending on the season and weather. Timing your search makes all the difference.

Spring

Spring brings a fresh wave of wild edible plants as the ground thaws and new growth begins:

| Plant | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | March–May | Cool, sunny fields and disturbed soil |

| Wild leeks (Allium tricoccum) | April–May | Cool, damp forest floor |

| Toothwort (Cardamine spp.) | March–May | Moist woodland areas after rainfall |

| Redbud (Cercis canadensis) | April–May | Mild sunny days in open woodlands |

| Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | March–May | Shady forest edges with moist soil |

| Ramsons (Allium ursinum) | April–May | Shady, wet woodland floors |

| Wild hyacinth (Camassia scilloides) | April–May | Moist open woods and meadows |

| Strawberry blite (Blitum capitatum) | April–June | Cool, moist soil in open areas |

| Violet wood sorrel (Oxalis violacea) | April–May | Moist forest edges |

| Chicory (Cichorium intybus) | May (early) | Sunny roadsides and grassy fields |

Summer

Summer is a peak season for foraging, with fruits, flowers, and greens growing in full force:

| Plant | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus) | June–August | Sunny thickets and forest clearings |

| Common dewberry (Rubus flagellaris) | June–July | Open fields and forest edges |

| Wild chives (Allium schoenoprasum) | June–August | Moist sunny meadows |

| Wild garlic (Allium vineale) | June–August | Sunny fields and lawns |

| Garden sage (Salvia officinalis) | June–September | Well-drained sunny garden beds |

| Garlic chives (Allium tuberosum) | July–September | Sunny herb gardens |

| Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) | June–August | Sunny roadsides and gardens |

| Curly dock (Rumex crispus) | June–August | Disturbed soil and ditches |

| Common mallow (Malva neglecta) | June–August | Disturbed soil in gardens and fields |

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | June–August | Dry sunny fields |

Fall

As temperatures drop, many edible plants shift underground or produce their last harvests:

| Plant | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | September–October | Moist woodland valleys and creek bottoms |

| Saskatoon (Amelanchier alnifolia) | August–September | Sunny forest edges |

| White mulberry (Morus alba) | August–September | Urban edges and woodland margins |

| American persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | October–November | Lowland forests after frost |

| Prairie crab apple (Malus ioensis) | September–October | Open woodlands and old pastures |

| Eastern black walnut (Juglans nigra) | September–October | Mature woods and floodplains |

| Sweet acorn oak (Quercus rotundifolia) | September–November | Oak forests and dry hillsides |

| Black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) | August–October | Wet thickets and forest margins |

| Wild sweet potato (Ipomoea pandurata) | September–October | Roadside ditches and open soil |

| Wild lettuce (Lactuca virosa) | September–October | Shaded disturbed ground |

Winter

Winter foraging is limited but still possible, with hardy plants and preserved growth holding on through the cold:

| Plant | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) | December–February | Cold upland forests with dry soil |

| Sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella) | November–February | Sunny disturbed soil or lawns |

| Lamb’s quarters (Chenopodium album) | November–February (dried) | Dried seed heads in fields |

| Endive (Cichorium endivia) | December–February | Frost-hardy urban and community plots |

| Common greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) | December–February | Thickets and vine-covered woods |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.