Georgia’s forests, fields, and creeks are home to a surprising variety of edible wild plants. You’ll find things like muscadine grapes tangled through the woods and chickweed growing low to the ground in disturbed soil. Some plants are easy to overlook until you know exactly what to notice.

There are edible flowers, roots, leaves, and even tree parts hiding in plain sight. Eastern redbud blossoms can be picked right off the branch, and greenbrier shoots are tender enough to eat raw. Not every wild plant is safe though, and some have close lookalikes that aren’t edible at all.

If you know what signs to pay attention to, you’ll start noticing edible species tucked into all kinds of different places. That’s when you realize just how many kinds of wild plants can end up in your basket in one day. There’s more growing out there than most people think.

What We Cover In This Article:

- The Edible Plants Found in the State

- Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

- How to Get the Best Results Foraging

- Where to Find Forageables in the State

- Peak Foraging Seasons

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

The Edible Plants Found in the State

Wild plants found across the state can add fresh, seasonal ingredients to your meals:

Black Walnut (Juglans nigra)

The nuts of the black walnut, sometimes called American walnut or eastern black walnut, have a tough outer husk and a deeply ridged shell inside. When you crack them open, you will find a rich, oily seed with an earthy, slightly bitter flavor that sets them apart from the sweeter English walnut.

It is easy to confuse black walnut with butternut, another tree with compound leaves and rough bark. If you check the nuts closely, black walnut fruits are round with a thick green husk, while butternuts are more oval and sticky.

When you get your hands on the nuts, the common ways to prepare them include baking them into cookies, sprinkling them over salads, or grinding them into a strong-tasting flour. The seeds themselves have a firm, almost chewy texture when raw and become crunchy after roasting.

Only the inner seed is eaten, while the outer husk and shell are discarded because they contain compounds that can irritate your skin. A fun fact about this plant is that even the roots and leaves produce a chemical called juglone, which can make it hard for other plants to grow nearby.

Chickweed (Stellaria media)

Chickweed, sometimes called satin flower or starweed, is a small, low-growing plant with delicate white star-shaped flowers and bright green leaves. The leaves are oval, pointed at the tip, and often grow in pairs along a slender, somewhat weak-looking stem.

When gathering chickweed, watch out for lookalikes like scarlet pimpernel, which has similar leaves but orange flowers instead of white. A key detail to check is the fine line of hairs that runs along one side of chickweed’s stem, a feature the dangerous lookalikes do not have.

The young leaves, tender stems, and flowers of chickweed are all edible, offering a mild, slightly grassy flavor with a crisp texture. You can toss it fresh into salads, blend it into pestos, or lightly wilt it into soups and stir-fries for a fresh green boost.

Aside from being a food plant, chickweed has been used traditionally in poultices and salves to help soothe skin irritations. Always make sure the plant is positively identified before eating, since mistaking it for a toxic lookalike could cause serious issues.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

Bright yellow flowers and jagged, deeply toothed leaves make dandelions easy to spot in open fields, lawns, and roadsides. You might also hear them called lion’s tooth, blowball, or puffball once the flowers turn into round, white seed heads.

Every part of the dandelion is edible, but you will want to avoid harvesting from places treated with pesticides or roadside areas with heavy car traffic. Besides being a food source, dandelions have been used traditionally for simple herbal remedies and natural dye projects.

Young dandelion leaves have a slightly bitter, peppery flavor that works well in salads or sautés, and the flowers can be fried into fritters or brewed into tea. Some people even roast the roots to make a coffee substitute with a rich, earthy taste.

One thing to watch out for is cat’s ear, a common lookalike with hairy leaves and branching flower stems instead of a single, hollow one. To make sure you have a true dandelion, check for a smooth, hairless stem that oozes a milky sap when broken.

Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva)

Bright orange flowers known as daylily, tiger lily, or ditch lily can sometimes be mistaken for other plants that are not safe to eat. True daylilies have long, blade-like leaves that grow in clumps at the base and a hollow flower stem, while their toxic lookalikes often have solid stems or different leaf patterns.

When it comes to flavor, daylily buds have a crisp texture and a mild taste that some people compare to green beans or asparagus. The flowers are tender and slightly sweet, which makes them popular for tossing into salads or lightly stir-frying.

Most people use the unopened flower buds in cooking, but the young shoots and tuber-like roots are also gathered for food. Always make sure you are harvesting from clean areas, because roadside plants can carry pollutants that are not safe to eat.

A few important cautions come with daylilies, since some people experience digestive upset after eating large amounts. Start by tasting a small quantity first to see how your body reacts before eating more.

Plantain (Plantago major)

Plantain, also called common plantain or narrowleaf plantain depending on the type, is a low-growing plant with broad or lance-shaped leaves and tall, slender flower spikes. The leaves grow in a rosette close to the ground, and the thick veins running through them are one of the easiest ways to tell it apart from other plants.

You can mainly eat the young leaves and the seeds of the plants. Older leaves can become tough and stringy, so it is best to pick the smaller, tender ones when you want to eat them.

Plantain leaves have a slightly bitter, earthy taste and a chewy texture, especially when eaten raw. Many people like to add them to salads, soups, or stews, or lightly steam them to soften the flavor.

Always make sure you have a true plantain before eating because some similar-looking yard plants are not palatable and can upset your stomach. Look for the strong parallel veins and the tough, fibrous stems to help confirm your find.

Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis)

The small, pinkish-purple flowers of the eastern redbud grow directly from the branches and even the trunk. These blooms are edible raw and have a slightly tangy, pea-like flavor that works well in salads or as a garnish.

You can also eat the young seed pods when they’re still flat and tender. They taste somewhat like snow peas and can be lightly steamed, stir-fried, or pickled.

Avoid older seed pods, which become tough and fibrous. Also be aware that while the flowers and young pods are safe to eat, the mature seeds and bark are not consumed.

Some people sprinkle the blossoms into baked goods for a splash of color and a mild floral note. Others like to candy the flowers, though they lose some of their fresh bite in the process.

Elderberry (Sambucus nigra subsp. canadensis)

Elderberry is often called American elder, common elder, or sweet elder. It grows as a large, shrubby plant with clusters of tiny white flowers that eventually turn into deep purple to black berries.

You can recognize elderberry by its compound leaves with five to eleven serrated leaflets and its flat-topped flower clusters. One important thing to watch out for is its toxic lookalikes, like pokeweed, which has very different smooth-edged leaves and reddish stems.

The ripe berries have a tart, almost earthy flavor and a soft texture when cooked. People usually cook elderberries into syrups, jams, pies, or wine because eating raw berries can cause nausea.

Only the ripe, cooked berries and flowers are edible, while the leaves, stems, and unripe berries are toxic. Always take care to strip the berries cleanly from their stems before using them, as even small bits of stem can cause problems.

Greenbrier (Smilax spp.)

Greenbrier vines grow in tangled masses, with edible tips that can be pinched off and cooked like vegetables. The young shoots snap easily and have a mild, slightly grassy taste.

Some vines look similar but lack the same curling tendrils or bear different leaf shapes. As long as you’re collecting only the soft green tips from a true greenbrier, you’ll be fine.

You can toss the shoots into a pan with garlic and oil, or just blanch and freeze them. People also grind the starchy roots into flour or use them to thicken stews.

The round, bluish or black berries are safe to eat, but they’re not very flavorful. Skip the tough stems—they’re too fibrous to eat and not worth the effort.

Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule)

Henbit, which is also known as giraffe head or henbit deadnettle, is a small plant with fuzzy, scalloped leaves and tiny pink-purple flowers. You can spot it easily by the way its square stems branch low to the ground while the leaves crowd around the stem in neat whorls.

The stems, leaves, and flowers are all edible and can be eaten raw or cooked. They have a mild, slightly sweet flavor with a soft texture that works well in salads, smoothies, or lightly sautéed dishes.

Henbit is often added fresh to salads or used as a tender green in soups and stir-fries. There is no need to cook it for long because it wilts quickly and can lose its flavor if overcooked.

It’s important to remember that henbit can look similar to purple deadnettle, but henbit’s leaves are more rounded and clasp the stem directly without long stalks. Another lookalike is ground ivy, which has a stronger smell and a creeping growth habit that henbit does not.

Passionflower (Passiflora incarnata)

With its intricate purple blooms and oval green fruits, passionflower grows on a vigorous vine and produces a soft, jelly-like pulp that’s edible when ripe. The taste is tart and sweet, with a strong tropical note that pairs well with sugar.

You can spoon the pulp straight from the rind, or boil it into preserves or syrups. Don’t eat the unripe fruit—it can cause nausea or cramping.

Passionflower vines can resemble wild cucumber or other vining species, but only passionflower produces that signature flower and edible fruit. Its fruit is filled with dozens of seeds, each wrapped in translucent orange pulp.

The rind isn’t eaten, and the rest of the plant isn’t used in cooking. When foraging, make sure the fruit has wrinkled slightly—that’s when the flavor and texture are at their best.

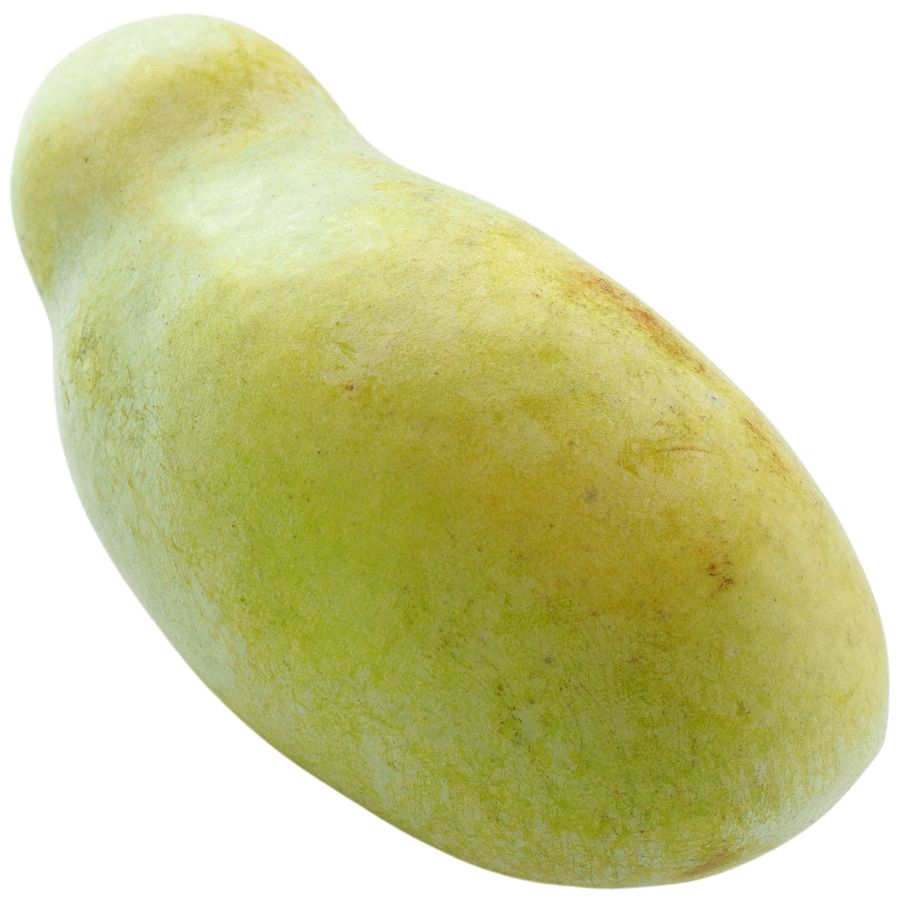

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba)

The pawpaw grows fruits that are green and shaped a little like small mangoes. Inside, the soft yellow flesh tastes like a blend of banana, mango, and melon, with a custard-like texture that melts in your mouth.

If you are comparing it to similar plants, keep in mind that young pawpaw trees can look a little like young magnolias because of their large leaves. True pawpaws grow fruits with large brown seeds tucked inside, while magnolias do not produce anything that looks or tastes similar.

You can eat the flesh straight out of the skin with a spoon, or mash it into puddings, smoothies, and even homemade ice cream. Some people also like to freeze it into cubes for later, although it does tend to brown quickly once exposed to air.

Stick to eating the soft inner flesh. Make sure not to ingest the skin and seeds of the fruit because they contain compounds that can upset your stomach.

This fruit is that it was a favorite snack of Native Americans and early explorers long before it started showing up in backyard gardens.

Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)

Persimmon, sometimes called American persimmon or common persimmon, grows as a small tree with rough, blocky bark and oval-shaped leaves. The fruit looks like a small, flattened tomato and turns a deep orange or reddish color when ripe.

If you bite into an unripe persimmon, you will quickly notice an extremely astringent, mouth-drying effect. A ripe persimmon, on the other hand, tastes sweet, rich, and custard-like, with a soft and jelly-like texture inside.

You can eat persimmons fresh once they are fully ripe, or you can cook them down into puddings, jams, and baked goods. Some people also mash and freeze the pulp to use later for pies, breads, and sauces.

Wild persimmons can sometimes be confused with black nightshade berries, but nightshade fruits are much smaller, grow in clusters, and stay dark purple or black. Only the ripe fruit of the persimmon tree should be eaten; the seeds and the unripe fruit are not edible.

Pine (Pinus spp.)

Pine trees offer several edible parts, including the fresh needles, which are used to make tea with a piney, slightly sour flavor. Their bundles of long, slender needles make them easy to separate from toxic lookalikes like yew, which has flat, single needles.

The seeds—pine nuts—are tucked away between the scales of mature cones and are highly nutritious. They’re often toasted to bring out their rich, oily flavor and are commonly added to trail mixes and pasta dishes.

You can scrape the soft white layer of inner bark and dry it into flour, though it’s mostly a fallback food. This layer is chewy when raw and works best when baked or roasted.

Not all pines are safe to eat, and some species contain compounds that can upset your stomach. When in doubt, Eastern White Pine is one of the most widely accepted edible types.

Sassafras (Sassafras albidum)

Sassafras is a small deciduous tree with bright green leaves that feel slightly mucilaginous when crushed. You can eat the young leaves raw or dried, and they develop a unique flavor—lightly citrusy, with a smooth texture when chewed.

People use the ground leaves as a thickener in soups and stews, especially in southern recipes. The bark and roots have a stronger taste and were historically brewed into teas with a deep, spicy profile.

There’s a caution with sassafras root: it contains safrole, which has been restricted from commercial food use due to safety studies. However, using a small amount occasionally in traditional preparations is still common in home kitchens.

The tree has a sweet, clove-like scent that sets it apart when the leaves or twigs are snapped. Its closest lookalikes lack that scent and don’t have the same combination of leaf shapes on a single branch.

Spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

Spicebush has smooth-edged leaves that release a spicy citrus scent when crushed, and it produces clusters of red berries that grow close to the stem. Those berries, along with the young twigs and leaves, are all edible and flavorful.

The berries are especially valued for their warm, peppery kick and are often dried and ground as a seasoning. You can steep the leaves and twigs into tea or simmer them into broths.

Avoid confusing it with lookalikes like Carolina allspice, which has larger, thicker leaves and lacks the same aromatic quality. Its berries also differ in size and internal seed structure.

Spicebush has a long history of use in traditional cooking for its mild numbing effect and warming flavor. Only the berries, leaves, and tender twigs should be consumed—avoid the bark and roots.

Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

Wild strawberry, sometimes called Virginia strawberry or mountain strawberry, grows low to the ground with three-part leaves that have jagged edges. The small white flowers with yellow centers eventually give way to tiny, bright red fruits nestled close to the soil.

The fruits are sweet with a burst of tartness, and their texture is much softer than the large cultivated strawberries you find in stores. You can eat them raw, mix them into jams, or bake them into pies for a rich, fruity flavor.

Wild strawberry can sometimes be confused with mock strawberry, which has similar leaves but produces dry, flavorless fruits and yellow flowers instead of white. Always check the flower color and taste a small piece before collecting more.

Only the berries and the tender young leaves of wild strawberry are edible, with the leaves often brewed into teas. Be careful not to overharvest because these plants grow slowly and support plenty of small wildlife.

Chicory (Cichorium intybus)

Chicory has bright blue flowers that open in the morning and close by afternoon. Its jagged leaves grow in a rosette close to the ground and can resemble dandelion leaves, but dandelions don’t have the same thick, hairy stems.

The leaves are bitter and slightly earthy, often compared to dandelion greens but with a stronger flavor. You can blanch or sauté them to mellow the bitterness, or chop them raw into salads if you like a sharper bite.

Its roots are the most commonly used part, especially when roasted and ground to mix into coffee or brewed as a caffeine-free drink on their own. They’re dense and woody, and once roasted, they take on a toasty, nutty flavor that balances well with richer foods.

Avoid confusing chicory with wild lettuce, which can grow in similar areas but has a milky sap and a more unpleasant taste. Chicory doesn’t have any toxic lookalikes, but the strong bitterness of mature leaves can be off-putting if you’re not expecting it.

Groundnut (Apios americana)

Groundnut is also called potato bean or Indian potato, and it grows as a climbing vine with clusters of pinkish-purple flowers. The part most people go for is the underground tuber, which looks a bit like a small, knobby chain of beads.

The flavor is richer than a regular potato, with a nutty, earthy taste and a dense, almost chestnut-like texture when cooked. It holds up well in soups and stews, or you can boil and mash it like a root vegetable.

Some people slice it thin and roast it until crisp, while others slow-cook it to bring out a sweeter taste. The vine also produces beans, but the root is what’s usually eaten.

There are a few vines that resemble groundnut, but many of those don’t have the same distinctive flower clusters or tend to lack the beadlike roots. Always make sure you’re digging up the right plant before cooking it.

Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus)

Jerusalem artichoke grows tall with sunflower-like blooms and has knobby underground tubers. The tubers are tan or reddish and look a bit like ginger root, though they belong to the sunflower family.

The part you’re after is the tuber, which has a nutty, slightly sweet flavor and a crisp texture when raw. You can roast, sauté, boil, or mash them like potatoes, and they hold their shape well in soups and stir-fries.

Some people experience gas or bloating after eating sunchokes due to the inulin they contain, so it’s a good idea to try a small amount first. Cooking them thoroughly can help reduce the chances of digestive discomfort.

Sunchokes don’t have many dangerous lookalikes, but it’s important not to confuse the plant with other sunflower relatives that don’t produce tubers. The above-ground part resembles a small sunflower, but it’s the knotted, underground tubers that are worth digging up.

Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album)

Lamb’s quarters, also called wild spinach and pigweed, has soft green leaves that often look dusted with a white, powdery coating. The leaves are shaped a little like goose feet, with slightly jagged edges and a smooth underside that feels almost velvety when you touch it.

A few plants can be confused with lamb’s quarters, like some types of nightshade, but true lamb’s quarters never have berries and its leaves are usually coated in that distinctive white bloom. Always check that the stems are grooved and not round and smooth like the poisonous lookalikes.

When you taste lamb’s quarters, you will notice it has a mild, slightly nutty flavor that gets richer when cooked. The young leaves, tender stems, and even the seeds are all edible, but you should avoid eating the older stems because they become tough and stringy.

People often sauté lamb’s quarters like spinach, blend it into smoothies, or dry the leaves for later use in soups and stews. It is also rich in oxalates, so you will want to cook it before eating large amounts to avoid any problems.

Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

There are plenty of wild edibles to choose from, but some toxic native plants closely resemble them. Mistaking the wrong one can lead to severe illness or even death, so it’s important to know exactly what you’re picking.

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild carrot (Daucus carota)

Poison hemlock is a tall plant with lacy leaves and umbrella-like clusters of tiny white flowers. It has smooth, hollow stems with purple blotches and grows in sunny places like roadsides, meadows, and stream banks.

Unlike wild carrot, which has hairy stems and a dark central floret, poison hemlock has a musty odor and no flower center spot. It’s extremely toxic; just a small amount can be fatal, and even touching the sap can irritate the skin.

Water Hemlock (Cicuta spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) or wild celery (Apium spp.)

Water hemlock is a tall, branching plant with umbrella-shaped clusters of small white flowers. It grows in wet places like stream banks, marshes, and ditches, with stems that often show purple streaks or spots.

It can be confused with wild parsnip or wild celery, but its thick, hollow roots have internal chambers and release a yellow, foul-smelling sap when cut. Water hemlock is the most toxic plant in North America, and just a small amount can cause seizures, respiratory failure, and death.

False Hellebore (Veratrum viride)

Often mistaken for: Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

False hellebore is a tall plant with broad, pleated green leaves that grow in a spiral from the base, often appearing early in spring. It grows in moist woods, meadows, and along streams.

It’s commonly mistaken for ramps, but ramps have a strong onion or garlic smell, while false hellebore is odorless and later grows a tall flower stalk. The plant is highly toxic, and eating any part can cause nausea, a slowed heart rate, and even death due to its alkaloids that affect the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Death Camas (Zigadenus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild onion or wild garlic (Allium spp.)

Death camas is a slender, grass-like plant that grows from underground bulbs and is found in open woods, meadows, and grassy hillsides. It has small, cream-colored flowers in loose clusters atop a tall stalk.

It’s often confused with wild onion or wild garlic due to their similar narrow leaves and habitats, but only Allium plants have a strong onion or garlic scent, while death camas has none. The plant is extremely poisonous, especially the bulbs, and even a small amount can cause nausea, vomiting, a slowed heartbeat, and potentially fatal respiratory failure.

Buckthorn Berries (Rhamnus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Elderberries (Sambucus spp.)

Buckthorn is a shrub or small tree often found along woodland edges, roadsides, and disturbed areas. It produces small, round berries that ripen to dark purple or black and usually grow in loose clusters.

These berries are sometimes mistaken for elderberries and other wild fruits, which also grow in dark clusters, but elderberries form flat-topped clusters on reddish stems while buckthorn berries are more scattered. Buckthorn berries are unsafe to eat as they contain compounds that can cause cramping, vomiting, and diarrhea, and large amounts may lead to dehydration and serious digestive problems.

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Mayapple is a low-growing plant found in shady forests and woodland clearings. It has large, umbrella-like leaves and produces a single pale fruit hidden beneath the foliage.

The unripe fruit resembles a small green grape, causing confusion with wild grapes, which grow in woody clusters on vines. All parts of the mayapple are toxic except the fully ripe, yellow fruit, which is only safe in small amounts. Eating unripe fruit or other parts can lead to nausea, vomiting, and severe dehydration.

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Virginia creeper is a fast-growing vine found on fences, trees, and forest edges. It has five leaflets per stem and produces small, bluish-purple berries from late summer to fall.

It’s often confused with wild grapes since both are climbing vines with similar berries, but grapevines have large, lobed single leaves and tighter fruit clusters. Virginia creeper’s berries are toxic to humans and contain oxalate crystals that can cause nausea, vomiting, and throat irritation.

Castor Bean (Ricinus communis)

Often mistaken for: Wild rhubarb (Rumex spp. or Rheum spp.)

Castor bean is a bold plant with large, lobed leaves and tall red or green stalks, often found in gardens, along roadsides, and in disturbed areas in warmer regions in the US. Its red-tinged stems and overall size can resemble wild rhubarb to the untrained eye.

Unlike rhubarb, castor bean plants produce spiny seed pods containing glossy, mottled seeds that are extremely toxic. These seeds contain ricin, a deadly compound even in small amounts. While all parts of the plant are toxic, the seeds are especially dangerous and should never be handled or ingested.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

How to Get the Best Results Foraging

Safety should always come first when it comes to foraging. Whether you’re in a rural forest or a suburban greenbelt, knowing how to harvest wild foods properly is a key part of staying safe and respectful in the field.

Always Confirm Plant ID Before You Harvest Anything

Knowing exactly what you’re picking is the most important part of safe foraging. Some edible plants have nearly identical toxic lookalikes, and a wrong guess can make you seriously sick.

Use more than one reliable source to confirm your ID, like field guides, apps, and trusted websites. Pay close attention to small details. Things like leaf shape, stem texture, and how the flowers or fruits are arranged all matter.

Not All Edible Plants Are Safe to Eat Whole

Just because a plant is edible doesn’t mean every part of it is safe. Some plants have leaves, stems, or seeds that can be toxic if eaten raw or prepared the wrong way.

For example, pokeweed is only safe when young and properly cooked, while elderberries need to be heated before eating. Rhubarb stems are fine, but the leaves are poisonous. Always look up which parts are edible and how they should be handled.

Avoid Foraging in Polluted or Contaminated Areas

Where you forage matters just as much as what you pick. Plants growing near roads, buildings, or farmland might be coated in chemicals or growing in polluted soil.

Even safe plants can take in harmful substances from the air, water, or ground. Stick to clean, natural areas like forests, local parks that allow foraging, or your own yard when possible.

Don’t Harvest More Than What You Need

When you forage, take only what you plan to use. Overharvesting can hurt local plant populations and reduce future growth in that area.

Leaving plenty behind helps plants reproduce and supports wildlife that depends on them. It also ensures other foragers have a chance to enjoy the same resources.

Protect Yourself and Your Finds with Proper Foraging Gear

Having the right tools makes foraging easier and safer. Gloves protect your hands from irritants like stinging nettle, and a good knife or scissors lets you harvest cleanly without damaging the plant.

Use a basket or breathable bag to carry what you collect. Plastic bags hold too much moisture and can cause your greens to spoil before you get home.

This forager’s toolkit covers the essentials for any level of experience.

Watch for Allergic Reactions When Trying New Wild Foods

Even if a wild plant is safe to eat, your body might react to it in unexpected ways. It’s best to try a small amount first and wait to see how you feel.

Be extra careful with kids or anyone who has allergies. A plant that’s harmless for one person could cause a reaction in someone else.

Check Local Rules Before Foraging on Any Land

Before you start foraging, make sure you know the rules for the area you’re in. What’s allowed in one spot might be completely off-limits just a few miles away.

Some public lands permit limited foraging, while others, like national parks, usually don’t allow it at all. If you’re on private property, always get permission first.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

Where to Find Forageables in the State

There is a range of foraging spots where edible plants grow naturally and often in abundance:

| Plant | Locations |

| Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | – Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forests – Ocmulgee River floodplain near Macon – Tallulah Gorge State Park |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | – Piedmont National Wildlife Refuge – Sweetwater Creek State Park – Urban green spaces in Atlanta |

| Chicory (Cichorium intybus) | – Roadside areas along US-441 – Fort Yargo State Park – Open fields in Oconee National Forest |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | – Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park – Cloudland Canyon State Park – Urban lawns and parks in Savannah |

| Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) | – Amicalola Falls State Park – Residential areas in Athens – Along trails in Vogel State Park |

| Plantain (Plantago major) | – Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area – Panola Mountain State Park – Greenways in Roswell |

| Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis) | – Hard Labor Creek State Park – Oconee National Forest – Along the Silver Comet Trail |

| Elderberry (Sambucus nigra subsp. canadensis) | – Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge – Along the Flint River – Black Rock Mountain State Park |

| Greenbrier (Smilax spp.) | – Coastal Plain regions – Crooked River State Park – Understory of mixed hardwood forests in North Georgia |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | – Wetlands in Piedmont National Wildlife Refuge – Along the Altamaha River – Swampy areas in Stephen C. Foster State Park |

| Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) | – Along the Chattahoochee River – Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park – Urban areas in Macon |

| Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule) | – Open fields in Fort Mountain State Park – Lawns in suburban Atlanta – Edges of agricultural fields in South Georgia |

| Hickory Nuts (Carya spp.) | – Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forests – High elevations in the Blue Ridge Mountains – Along the Oconee River |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | – Along the Savannah River – Open areas in Tallulah Gorge State Park – Edges of agricultural fields in Central Georgia |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | – Disturbed soils in Providence Canyon State Park – Community gardens in Atlanta – Along trails in Red Top Mountain State Park |

| Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum) | – Shaded areas in Vogel State Park – Understory of hardwood forests in North Georgia – Along streams in Fort Mountain State Park |

| Muscadine Grapes (Vitis rotundifolia) | – Coastal woodlands – Crooked River State Park – Along fences and trellises in rural areas |

| Passionflower (Passiflora incarnata) | – Open fields in Hard Labor Creek State Park – Along the Ogeechee River – Edges of forests in Middle Georgia |

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | – Bottomlands in Chattahoochee National Forest – Along the Flint River – Shaded areas in Sweetwater Creek State Park |

| Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | – Open woods in Oconee National Forest – Along the Altamaha River – Urban parks in Augusta |

| Pine (Pinus spp.) | – Widely distributed across Georgia – Pine Mountain Trail – General Coffee State Park |

| Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia humifusa) | – Sandy soils in Coastal Plain – Cumberland Island National Seashore – Along trails in Reed Bingham State Park |

| Red Maple (Acer rubrum) | – Wetlands in Okefenokee Swamp – Along the Ocmulgee River – Mixed forests in North Georgia |

| Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) | – Understory of hardwood forests in Chattahoochee National Forest – Along trails in Fort Mountain State Park – Edges of fields in Middle Georgia |

| Sheep Sorrel (Rumex acetosella) | – Open fields in Providence Canyon State Park – Along roadsides in South Georgia – Disturbed soils in Piedmont region |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | – Moist forests in Vogel State Park – Along streams in North Georgia – Understory of hardwood forests in Oconee National Forest |

| Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) | – Rich soils along the Chattahoochee River – Shaded areas in Tallulah Gorge State Park – Moist areas in Fort Yargo State Park |

| Sumac (Rhus spp.) | – Along roadsides in North Georgia – Open fields in Cloudland Canyon State Park – Edges of forests in Middle Georgia |

| Violet (Viola sororia) | – Shaded lawns in urban areas – Understory of hardwood forests in North Georgia – Along trails in Sweetwater Creek State Park |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | – Clear streams in Chattahoochee National Forest – Springs in North Georgia mountains – Along creeks in Fort Mountain State Park |

| Wild Garlic (Allium vineale) | – Open fields in South Georgia – Lawns in suburban Atlanta – Along trails in Red Top Mountain State Park |

| Wild Onion (Allium canadense) | – Meadows in Piedmont region – Along the Ocmulgee River – Open woods in Oconee National Forest |

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) | – Open areas in Vogel State Park – Along trails in Fort Mountain State Park – Meadows in North Georgia |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis spp.) | – Shaded areas in Chattahoochee National Forest – Lawns in urban areas – Along trails in Sweetwater Creek State Park |

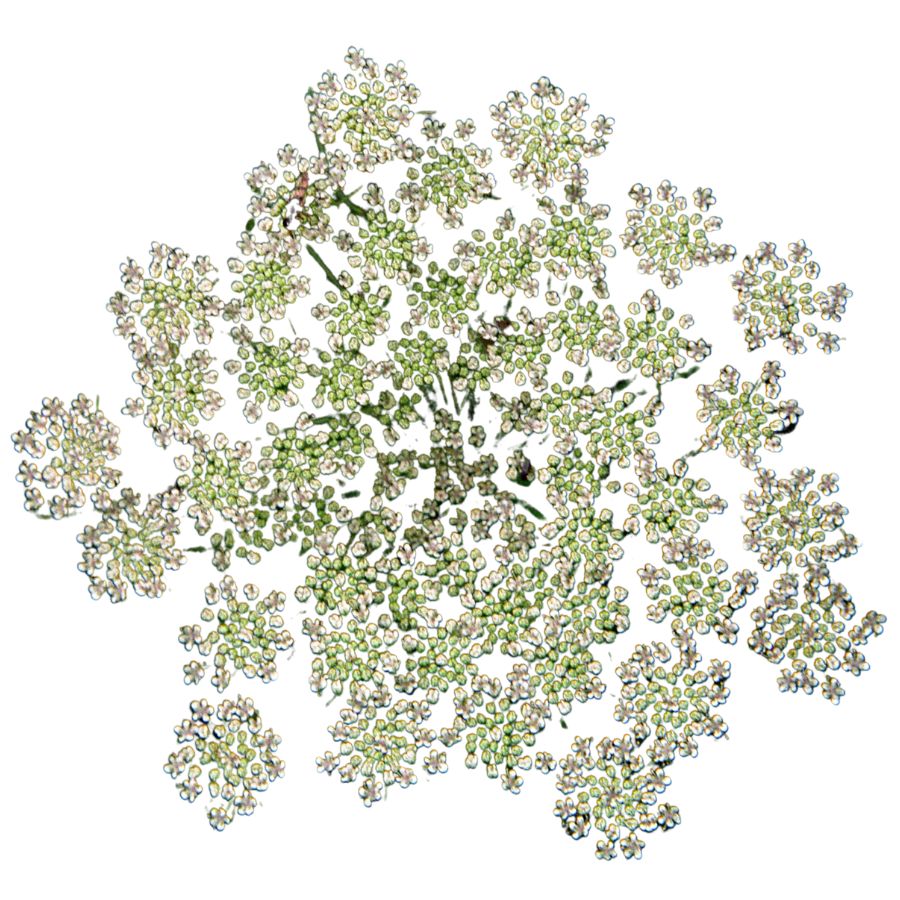

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | – Open fields in Providence Canyon State Park – Along roadsides in North Georgia – Meadows in Fort Mountain State Park |

Peak Foraging Seasons

Different edible plants grow at different times of year, depending on the season and weather. Timing your search makes all the difference.

Spring

Spring brings a fresh wave of wild edible plants as the ground thaws and new growth begins:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | March–May | Cool, moist conditions after rain |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | March–May | Sunny days after light rain |

| Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis) | March–April | Warm, dry days |

| Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule) | February–April | Cool, damp conditions |

| Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum) | April–May | Partly shaded forest floor, moist soil |

| Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) | March–May | Cool, moist conditions |

| Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica) | March–May | Cool mornings with moist soil |

| Violet (Viola sororia) | March–May | Shaded, moist environments |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | March–May | Cool, flowing clean water |

| Wild Garlic (Allium vineale) | March–May | After rain, cool sunny days |

| Wild Onion (Allium canadense) | March–May | Cool weather after rainfall |

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) | April–May | Mild temperatures and moist soil |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis spp.) | March–May | Moist, partly shady spots |

Summer

Summer is a peak season for foraging, with fruits, flowers, and greens growing in full force:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Chicory (Cichorium intybus) | June–August | Hot, dry open areas |

| Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) | June–July | Warm sunny days |

| Elderberry (Sambucus nigra subsp. canadensis) | June–August | Humid weather, near water |

| Greenbrier (Smilax spp.) | May–August | Humid, shaded forest edges |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | June–August | Warm, disturbed soil areas |

| Muscadine Grapes (Vitis rotundifolia) | July–September | Hot and sunny |

| Passionflower (Passiflora incarnata) | June–August | Warm weather with good sun |

| Pine (Pinus spp.) | June–August | Dry, warm conditions for inner bark |

| Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia humifusa) | June–August | Hot, dry areas |

| Sheep Sorrel (Rumex acetosella) | May–August | Dry, open clearings |

| Sumac (Rhus spp.) | July–September | Hot sunny days |

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | May–August | Warm, dry meadows |

Fall

As temperatures drop, many edible plants shift underground or produce their last harvests:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | September–October | Dry days after nuts fall |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | September–November | Moist soil near water in cool weather |

| Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) | September–November | Cool, dry weather |

| Hickory Nuts (Carya spp.) | September–October | Cool dry conditions |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | October–November | Cool, moist soil |

| Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) | August–October | Humid forest understories |

| Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) | September–November | After first frost for best flavor |

| Red Maple (Acer rubrum) | September–November | Cool weather, moist forest edges |

| Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) | September–November | Cool weather, partly shaded areas |

Winter

Winter foraging is limited but still possible, with hardy plants and preserved growth holding on through the cold:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | December–February | Mild winters, moist soil |

| Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule) | January–February | Cool damp ground |

| Plantain (Plantago major) | December–February | Mild days, dormant rosettes visible |

| Sheep Sorrel (Rumex acetosella) | December–February | Cold but snow-free conditions |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | December–February | Cold streams, unfrozen water |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis spp.) | December–February | Mild winters, moist shaded areas |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.