Edible plants grow wild throughout Connecticut, from low woodlands to old fields and roadsides. Garlic mustard and lamb’s quarters are two that offer both flavor and nutrition, and they’re surprisingly easy to recognize once you’ve seen them a few times.

But for every common or well-known plant, there are others most people overlook completely, even when they walk right past them.

Sweet goldenrod might catch your eye with its vivid yellow flowers, but its edible leaves are what make it stand out. Coltsfoot is another one to keep in mind, especially early in the season when its flowers emerge before its leaves. These plants are useful for more than just their novelty.

There are far more edible species in Connecticut than most people realize, and even the ones that seem ordinary often have valuable uses. Knowing what a few of them look like is just the beginning. With a little attention, you can bring home an impressive variety of edible plants that grow all around the state.

What We Cover In This Article:

- The Edible Plants Found in the State

- Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

- How to Get the Best Results Foraging

- Where to Find Forageables in the State

- Peak Foraging Seasons

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

The Edible Plants Found in the State

Wild plants found across the state can add fresh, seasonal ingredients to your meals:

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

Bright yellow flowers and jagged, deeply toothed leaves make dandelions easy to spot in open fields, lawns, and roadsides. You might also hear them called lion’s tooth, blowball, or puffball once the flowers turn into round, white seed heads.

Every part of the dandelion is edible, but you will want to avoid harvesting from places treated with pesticides or roadside areas with heavy car traffic. Besides being a food source, dandelions have been used traditionally for simple herbal remedies and natural dye projects.

Young dandelion leaves have a slightly bitter, peppery flavor that works well in salads or sautés, and the flowers can be fried into fritters or brewed into tea. Some people even roast the roots to make a coffee substitute with a rich, earthy taste.

One thing to watch out for is cat’s ear, a common lookalike with hairy leaves and branching flower stems instead of a single, hollow one. To make sure you have a true dandelion, check for a smooth, hairless stem that oozes a milky sap when broken.

Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

Garlic mustard, sometimes called poor man’s mustard or hedge garlic, has heart-shaped leaves with scalloped edges and small white four-petaled flowers. When you crush the leaves between your fingers, they release a strong garlic-like smell that makes it stand out from similar-looking plants.

The flavor of garlic mustard is sharp and garlicky at first bite, with a peppery bitterness that lingers. Its young leaves are often blended into pestos, stirred into soups, or tossed into salads to add a punch of flavor.

You can also use the roots, which have a taste similar to horseradish when fresh. The seed pods are sometimes collected and used as a spicy seasoning after being dried and crushed.

If you decide to gather some, make sure not to confuse it with plants like ground ivy or purple deadnettle, which do not have that garlic aroma. Stick to harvesting the leaves, flowers, seeds, and roots, and avoid anything with a fuzzy texture or a very different smell.

Plantain (Plantago major)

Plantain, also called common plantain or narrowleaf plantain depending on the type, is a low-growing plant with broad or lance-shaped leaves and tall, slender flower spikes. The leaves grow in a rosette close to the ground, and the thick veins running through them are one of the easiest ways to tell it apart from other plants.

You can mainly eat the young leaves and the seeds of the plants. Older leaves can become tough and stringy, so it is best to pick the smaller, tender ones when you want to eat them.

Plantain leaves have a slightly bitter, earthy taste and a chewy texture, especially when eaten raw. Many people like to add them to salads, soups, or stews, or lightly steam them to soften the flavor.

Always make sure you have a true plantain before eating because some similar-looking yard plants are not palatable and can upset your stomach. Look for the strong parallel veins and the tough, fibrous stems to help confirm your find.

Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album)

Lamb’s quarters, also called wild spinach and pigweed, has soft green leaves that often look dusted with a white, powdery coating. The leaves are shaped a little like goose feet, with slightly jagged edges and a smooth underside that feels almost velvety when you touch it.

A few plants can be confused with lamb’s quarters, like some types of nightshade, but true lamb’s quarters never have berries and its leaves are usually coated in that distinctive white bloom. Always check that the stems are grooved and not round and smooth like the poisonous lookalikes.

When you taste lamb’s quarters, you will notice it has a mild, slightly nutty flavor that gets richer when cooked. The young leaves, tender stems, and even the seeds are all edible, but you should avoid eating the older stems because they become tough and stringy.

People often sauté lamb’s quarters like spinach, blend it into smoothies, or dry the leaves for later use in soups and stews. It is also rich in oxalates, so you will want to cook it before eating large amounts to avoid any problems.

Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta)

Wood sorrel has clover-like leaves and small yellow flowers. Each leaflet is heart-shaped, and the plant often folds up when touched or in low light.

The leaves, flowers, and seed pods are all safe to eat and have a tart, lemony flavor thanks to the oxalic acid they contain. You can toss them into salads, use them as a garnish, or nibble on them raw for a refreshing sour bite.

Be careful not to confuse it with clover, which has rounder leaves and lacks the same sharp tang when tasted. Large amounts of wood sorrel aren’t recommended if you have kidney issues, since oxalic acid can be hard on the kidneys over time.

The texture of the leaves is soft and delicate, making them a nice contrast in dishes with heavier greens. Even the seed pods have a bit of crunch and a pleasant tang if you catch them before they dry out.

Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica)

With its reddish-green stems and large spade-shaped leaves, Japanese knotweed—also called monkey weed—can be a surprisingly tasty wild ingredient. It has a strong, lemony flavor that mellows with cooking and pairs well with fruit.

People sometimes confuse it with giant ragweed or pokeweed, but knotweed stems are smooth, hollow, and ridged at the nodes, unlike the solid or grooved stems of those toxic lookalikes. Always focus on the young, flexible shoots, discarding any that feel stiff or woody.

Simmered into jams, blended into dressings, or used in baked goods, this plant transforms into something tart and refreshing. Peeled stalks can also be quick-pickled or sautéed.

You don’t want to eat the leaves or roots, and it’s smart to avoid areas sprayed with herbicides. Despite being considered a nuisance plant, it’s highly versatile in the kitchen.

Spearmint (Mentha spicata)

Fresh spearmint has serrated, pointed leaves and square stems that give it away in the mint family. The leaves release a crisp, slightly sweet scent when crushed, helping you separate it from non-edible mints like pennyroyal, which smells more pungent and medicinal.

You can eat the leaves raw, and they’re often used to brighten up salads, drinks, or yogurt sauces. The texture is soft and slightly fuzzy, and the taste is clean and mildly cooling without the strong menthol kick of peppermint.

Spearmint’s flavor makes it ideal for infusing into syrups or steeping in tea, especially when you want something soothing but not overpowering. You can also chop the leaves and stir them into cold desserts or use them to finish grilled meats.

Only the leaves and tender tops are edible; the older, woodier stems aren’t pleasant to chew. Stay clear of any wild mints with coarse, bristly leaves or those that lack that sharp, fresh aroma when pinched.

Mountain Mint (Pycnanthemum virginianum)

If you come across a strong herbal scent while brushing through wild grass, there’s a good chance mountain mint is nearby. This edible plant has thin, toothed leaves arranged oppositely on stiff square stems, and the leaves are what you’ll want to harvest.

It has a biting mint flavor with slightly earthy tones that works well in teas, savory marinades, or even mixed into ground meats for a fresh kick. The plant resembles a few other wild mints, but unlike potentially toxic lookalikes, mountain mint doesn’t have a dense, oily sheen or fuzzy undersides.

Drying the leaves intensifies the minty character, which can be used long after harvest in spice blends or herbal vinegars. You don’t need much—its taste carries through in even small pinches.

Always crush the leaf between your fingers and give it a sniff to confirm before using, especially if you’re in an area with multiple wild mint species. While it’s safe in moderation, consuming large amounts might leave you with an upset stomach or dry mouth.

Sweet Goldenrod (Solidago odora)

You can identify sweet goldenrod by its tall, branching stems topped with narrow yellow flower clusters and its narrow, lance-shaped leaves that smell like anise when crushed. The flowers aren’t edible, but the leaves and stems are commonly used for tea or infused syrups.

Its strong licorice flavor has a smooth, almost minty finish that comes through clearly when steeped. The texture of the raw leaves is coarse, so they’re usually dried and used rather than eaten fresh.

Lookalikes like Canada goldenrod or tall goldenrod lack the distinctive sweet scent of sweet goldenrod’s leaves, making scent a key way to tell them apart. Those other species are generally not harmful, but they don’t taste good and aren’t commonly used in food.

Infused oils, teas, and herbal jellies are common ways to preserve the leaves and young stems. Avoid the roots and flowers, which don’t have the same flavor and aren’t used in culinary preparations.

Cleavers (Galium aparine)

The sticky-stemmed plant cleavers, also called goosegrass and catchweed, has square stems covered in tiny hooked hairs that cling to your skin and clothing. Its whorled leaves grow in tight circles and have the same Velcro-like surface that makes the whole plant feel bristly.

You can eat the tender tips raw, though they’re fibrous and better when steamed, simmered into broth, or pureed for juice. The taste is mild and green, but the texture is stringy unless you cook it down or strain it.

Cleavers are sometimes confused with sweet woodruff, which shares a similar leaf arrangement but has smoother stems and a sweet scent when dried. Don’t mix them up with hedge bedstraw either—cleavers has that signature clinging texture, while hedge bedstraw lacks the hooked hairs.

Avoid the mature stems unless you’re making tea; they’re too tough to chew. Most people stick to eating the young leaves and stems, which can be blended into green drinks or cooked like spinach.

Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

Wild strawberry, sometimes called Virginia strawberry or mountain strawberry, grows low to the ground with three-part leaves that have jagged edges. The small white flowers with yellow centers eventually give way to tiny, bright red fruits nestled close to the soil.

The fruits are sweet with a burst of tartness, and their texture is much softer than the large cultivated strawberries you find in stores. You can eat them raw, mix them into jams, or bake them into pies for a rich, fruity flavor.

Wild strawberry can sometimes be confused with mock strawberry, which has similar leaves but produces dry, flavorless fruits and yellow flowers instead of white. Always check the flower color and taste a small piece before collecting more.

Only the berries and the tender young leaves of wild strawberry are edible, with the leaves often brewed into teas. Be careful not to overharvest because these plants grow slowly and support plenty of small wildlife.

Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata)

With its silver-dusted leaves and small, speckled red fruits, autumn olive—also called silverberry or Japanese silverberry—has made its way into many thickets and field edges. The fruit is edible, tart, and slick-skinned, with a burst of sourness that mellows in cooked preparations.

People often turn autumn olive into jelly, sauces, or fermented beverages to tame the intense flavor. You can also dehydrate the berries into a powder for use in baked goods.

Some confuse it with Russian olive, which grows similar leaves but bears dry, yellow fruit instead. Stick to harvesting just the berries, as the rest of the plant doesn’t have any culinary use.

What makes autumn olive particularly interesting is its nitrogen-fixing ability, which helps it thrive where other plants struggle—but that same trait is also why it spreads so aggressively. Still, the fruit is safe and edible, and one of the few wild berries with such a high lycopene content.

Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum)

Highbush cranberries grow in tight, red clusters and look a lot like small cherries, but the flavor is intensely tart with a musky edge. When fully ripe, you can use them to make sauces, jellies, or fruit leathers that hold up well in storage.

Don’t confuse this plant with European cranberrybush, which looks nearly identical but has fruit with an unpleasant odor and bitterness that lingers. Highbush cranberry leaves have three lobes, somewhat maple-like, while the European version often has a more rounded leaf base.

Each berry has a single flat seed shaped like a fish vertebra, which is a helpful trait when checking your harvest. The fruit’s texture is soft and slightly sticky, especially when cooked down.

Stick to the ripe berries—everything else, including the seeds and leaves, isn’t used for food. Highbush cranberry’s appeal lies in how it bridges the gap between sweet and sour, giving preserves a depth you won’t get from cultivated cranberries.

Black Walnut (Juglans nigra)

The nuts of the black walnut, sometimes called American walnut or eastern black walnut, have a tough outer husk and a deeply ridged shell inside. When you crack them open, you will find a rich, oily seed with an earthy, slightly bitter flavor that sets them apart from the sweeter English walnut.

It is easy to confuse black walnut with butternut, another tree with compound leaves and rough bark. If you check the nuts closely, black walnut fruits are round with a thick green husk, while butternuts are more oval and sticky.

When you get your hands on the nuts, the common ways to prepare them include baking them into cookies, sprinkling them over salads, or grinding them into a strong-tasting flour. The seeds themselves have a firm, almost chewy texture when raw and become crunchy after roasting.

Only the inner seed is eaten, while the outer husk and shell are discarded because they contain compounds that can irritate your skin. A fun fact about this plant is that even the roots and leaves produce a chemical called juglone, which can make it hard for other plants to grow nearby.

Beech (Fagus grandifolia)

From the American beech tree—also nicknamed white beech—you can collect small, three-sided nuts that are tightly enclosed in a spiny outer husk. They’re best roasted or pan-dried to bring out their buttery texture and mellow flavor.

The husks naturally open on their own once the nuts are ready, and you’ll often find two shiny brown seeds inside. Don’t eat them raw in large amounts, since they contain small amounts of oxalic acid that cooking neutralizes.

Beech trees are easy to confuse with chestnut trees at a glance, but chestnut leaves have longer tapering tips and the husks are far more heavily armored with spines. Avoid picking from horse chestnut, which has poisonous seeds that look similar.

Once prepared, the nuts can be added to soups or ground into a coarse flour for baked goods. Nothing else from the tree is eaten—only the seeds inside the husks are used.

Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana)

With its jagged green leaves and deep taproot, horseradish has one of the strongest-flavored edible roots you’ll come across. The root delivers a punch of heat that’s more nasal than tongue-based, unlike chili peppers.

Some confuse its leaves with wild burdock or dock, but horseradish gives off a sharp scent when snapped or scratched that those plants lack. The leaves are large and veined, but they’re not the main attraction.

Grated horseradish is typically pickled or added to sauces like cocktail sauce or horseradish cream for beef dishes. Left raw, it loses potency quickly unless combined with vinegar.

Don’t eat the flowers or stem—they’re technically not harmful, but they offer no flavor and aren’t used in cooking. The root, when properly handled, becomes a powerful ingredient with a crisp texture and eye-watering bite.

Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens)

If you find a trailing plant with white-veined, dark green leaves and waxy red berries, you’re probably looking at wintergreen. The plant carries a cool mint-like flavor that lingers on the tongue when you chew the berries or leaves.

Its flavor comes from methyl salicylate, which is safe in small amounts but concentrated enough that it shouldn’t be overused. People often use the leaves to make teas or candy infusions with a crisp, sweet finish.

Only the leaves and berries are edible—avoid eating the woody stems or roots, which are too tough and lack flavor. The berries have a chewy skin and taste like wintermint gum when ripe.

Teaberry is a common nickname for wintergreen’s fruit, which is mildly sweet but more useful for flavoring than for bulk snacking. Indian pipe can grow nearby and resembles it slightly, but it lacks any leaf or mint scent and isn’t edible.

Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara)

Coltsfoot, also called coughwort or horsehoof, puts out bright yellow flowers on short, scaly stems before any leaves appear. Once the flowers fade, broad, hoof-shaped leaves emerge, covered with a white fuzz on the underside.

The flower stalks look a lot like dandelions at first, but they’re reddish and scale-covered, not smooth and green. Dandelion leaves are also deeply toothed, while coltsfoot’s are more rounded and less serrated.

You can eat the flowers raw or turn them into candies and honey infusions, but the young leaves are usually boiled or sautéed to improve the texture. When cooked, the leaves have a spinach-like feel but keep a slightly bitter aftertaste.

It’s important not to use the root or overconsume the leaves due to naturally occurring alkaloids that can harm your liver over time. Stick to occasional use, especially when making homemade herbal candies or tea.

Virginia Waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginianum)

The plant Virginia waterleaf, also called Eastern waterleaf, has deeply lobed green leaves often marked with pale, water-stained blotches. It produces clusters of small purplish or bluish flowers on hairy stems, and the leaves grow in loose, low mounds.

You can eat the young leaves raw or cooked, and they have a mild, slightly tangy flavor with a soft spinach-like texture. Many people sauté them with garlic or mix them into soups and stews the way you would use other leafy greens.

It’s important not to confuse Virginia waterleaf with other woodland plants like poison hemlock or wild comfrey—those have different leaf patterns and lack the same blotchy markings. The stems and flowers are also edible, though older ones can get fibrous and less appealing.

There are no significant toxicity concerns with Virginia waterleaf, though the older leaves may develop a bitter aftertaste. If you harvest carefully, it can be a valuable wild green for cooking or adding to foraged salads.

Common Knotgrass (Polygonum aviculare)

If you spot a ground-hugging tangle of reddish stems and small, oval leaves arranged alternately, there’s a good chance it’s common knotgrass. This plant produces tiny, pale pink flowers tucked into the leaf axils that are easy to miss unless you’re looking closely.

The stems and leaves are the edible parts, and while you can eat them raw, they’re better tossed into a stir-fry or boiled like spinach. The flavor is subtle but slightly grassy, not unlike dock or mild arugula.

Sheep sorrel is sometimes mistaken for it, but sorrel has more distinctly arrow-shaped leaves and a tart, lemony bite. Always double-check the stem structure—knotgrass stems are jointed and slender, without the sour taste.

The plant also has a tendency to collect dust and grit close to trails and roads, so wash it thoroughly. It’s a tough little green that’s been used in wartime soups when other vegetables were scarce.

Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

There are plenty of wild edibles to choose from, but some toxic native plants closely resemble them. Mistaking the wrong one can lead to severe illness or even death, so it’s important to know exactly what you’re picking.

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild carrot (Daucus carota)

Poison hemlock is a tall plant with lacy leaves and umbrella-like clusters of tiny white flowers. It has smooth, hollow stems with purple blotches and grows in sunny places like roadsides, meadows, and stream banks.

Unlike wild carrot, which has hairy stems and a dark central floret, poison hemlock has a musty odor and no flower center spot. It’s extremely toxic; just a small amount can be fatal, and even touching the sap can irritate the skin.

Water Hemlock (Cicuta spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) or wild celery (Apium spp.)

Water hemlock is a tall, branching plant with umbrella-shaped clusters of small white flowers. It grows in wet places like stream banks, marshes, and ditches, with stems that often show purple streaks or spots.

It can be confused with wild parsnip or wild celery, but its thick, hollow roots have internal chambers and release a yellow, foul-smelling sap when cut. Water hemlock is the most toxic plant in North America, and just a small amount can cause seizures, respiratory failure, and death.

False Hellebore (Veratrum viride)

Often mistaken for: Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

False hellebore is a tall plant with broad, pleated green leaves that grow in a spiral from the base, often appearing early in spring. It grows in moist woods, meadows, and along streams.

It’s commonly mistaken for ramps, but ramps have a strong onion or garlic smell, while false hellebore is odorless and later grows a tall flower stalk. The plant is highly toxic, and eating any part can cause nausea, a slowed heart rate, and even death due to its alkaloids that affect the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Death Camas (Zigadenus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild onion or wild garlic (Allium spp.)

Death camas is a slender, grass-like plant that grows from underground bulbs and is found in open woods, meadows, and grassy hillsides. It has small, cream-colored flowers in loose clusters atop a tall stalk.

It’s often confused with wild onion or wild garlic due to their similar narrow leaves and habitats, but only Allium plants have a strong onion or garlic scent, while death camas has none. The plant is extremely poisonous, especially the bulbs, and even a small amount can cause nausea, vomiting, a slowed heartbeat, and potentially fatal respiratory failure.

Buckthorn Berries (Rhamnus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Elderberries (Sambucus spp.)

Buckthorn is a shrub or small tree often found along woodland edges, roadsides, and disturbed areas. It produces small, round berries that ripen to dark purple or black and usually grow in loose clusters.

These berries are sometimes mistaken for elderberries and other wild fruits, which also grow in dark clusters, but elderberries form flat-topped clusters on reddish stems while buckthorn berries are more scattered. Buckthorn berries are unsafe to eat as they contain compounds that can cause cramping, vomiting, and diarrhea, and large amounts may lead to dehydration and serious digestive problems.

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Mayapple is a low-growing plant found in shady forests and woodland clearings. It has large, umbrella-like leaves and produces a single pale fruit hidden beneath the foliage.

The unripe fruit resembles a small green grape, causing confusion with wild grapes, which grow in woody clusters on vines. All parts of the mayapple are toxic except the fully ripe, yellow fruit, which is only safe in small amounts. Eating unripe fruit or other parts can lead to nausea, vomiting, and severe dehydration.

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Virginia creeper is a fast-growing vine found on fences, trees, and forest edges. It has five leaflets per stem and produces small, bluish-purple berries from late summer to fall.

It’s often confused with wild grapes since both are climbing vines with similar berries, but grapevines have large, lobed single leaves and tighter fruit clusters. Virginia creeper’s berries are toxic to humans and contain oxalate crystals that can cause nausea, vomiting, and throat irritation.

Castor Bean (Ricinus communis)

Often mistaken for: Wild rhubarb (Rumex spp. or Rheum spp.)

Castor bean is a bold plant with large, lobed leaves and tall red or green stalks, often found in gardens, along roadsides, and in disturbed areas in warmer regions in the US. Its red-tinged stems and overall size can resemble wild rhubarb to the untrained eye.

Unlike rhubarb, castor bean plants produce spiny seed pods containing glossy, mottled seeds that are extremely toxic. These seeds contain ricin, a deadly compound even in small amounts. While all parts of the plant are toxic, the seeds are especially dangerous and should never be handled or ingested.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

How to Get the Best Results Foraging

Safety should always come first when it comes to foraging. Whether you’re in a rural forest or a suburban greenbelt, knowing how to harvest wild foods properly is a key part of staying safe and respectful in the field.

Always Confirm Plant ID Before You Harvest Anything

Knowing exactly what you’re picking is the most important part of safe foraging. Some edible plants have nearly identical toxic lookalikes, and a wrong guess can make you seriously sick.

Use more than one reliable source to confirm your ID, like field guides, apps, and trusted websites. Pay close attention to small details. Things like leaf shape, stem texture, and how the flowers or fruits are arranged all matter.

Not All Edible Plants Are Safe to Eat Whole

Just because a plant is edible doesn’t mean every part of it is safe. Some plants have leaves, stems, or seeds that can be toxic if eaten raw or prepared the wrong way.

For example, pokeweed is only safe when young and properly cooked, while elderberries need to be heated before eating. Rhubarb stems are fine, but the leaves are poisonous. Always look up which parts are edible and how they should be handled.

Avoid Foraging in Polluted or Contaminated Areas

Where you forage matters just as much as what you pick. Plants growing near roads, buildings, or farmland might be coated in chemicals or growing in polluted soil.

Even safe plants can take in harmful substances from the air, water, or ground. Stick to clean, natural areas like forests, local parks that allow foraging, or your own yard when possible.

Don’t Harvest More Than What You Need

When you forage, take only what you plan to use. Overharvesting can hurt local plant populations and reduce future growth in that area.

Leaving plenty behind helps plants reproduce and supports wildlife that depends on them. It also ensures other foragers have a chance to enjoy the same resources.

Protect Yourself and Your Finds with Proper Foraging Gear

Having the right tools makes foraging easier and safer. Gloves protect your hands from irritants like stinging nettle, and a good knife or scissors lets you harvest cleanly without damaging the plant.

Use a basket or breathable bag to carry what you collect. Plastic bags hold too much moisture and can cause your greens to spoil before you get home.

This forager’s toolkit covers the essentials for any level of experience.

Watch for Allergic Reactions When Trying New Wild Foods

Even if a wild plant is safe to eat, your body might react to it in unexpected ways. It’s best to try a small amount first and wait to see how you feel.

Be extra careful with kids or anyone who has allergies. A plant that’s harmless for one person could cause a reaction in someone else.

Check Local Rules Before Foraging on Any Land

Before you start foraging, make sure you know the rules for the area you’re in. What’s allowed in one spot might be completely off-limits just a few miles away.

Some public lands permit limited foraging, while others, like national parks, usually don’t allow it at all. If you’re on private property, always get permission first.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

Where to Find Forageables in the State

There is a range of foraging spots where edible plants grow naturally and often in abundance:

| Plant | Locations |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | – Black Sun Farm, Danielson – Bigelow Hollow State Park, Union – Community gardens and public meadows statewide |

| Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | – Branford Land Trust, Branford – Woodlands and shaded field edges throughout Connecticut – Disturbed areas and roadsides across the state |

| Plantain (Plantago major) | – Lawns and parks in Hartford – Gardens and disturbed soils statewide – Trails and compacted soils in various regions |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | – Community gardens in New Haven – Fields and disturbed areas across Connecticut – Roadsides and vacant lots statewide |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | – Gardens and shaded areas in Hartford – Community gardens throughout Connecticut – Sheltered areas near homes and foundations |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | – Fields and roadsides in Wallingford – Open areas and disturbed soils statewide – Meadows and forest edges across Connecticut |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta) | – Meadows and fields in various regions – Strawberry plantings and gardens statewide – Woodland areas throughout Connecticut |

| Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) | – Stream banks and riparian zones across the state – Moist areas and disturbed sites statewide – Behind parking lot on Water Street, Chester |

| Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) | – Meadows and open fields in various regions – Edges of woodlands across Connecticut – Pollinator gardens and naturalized areas statewide |

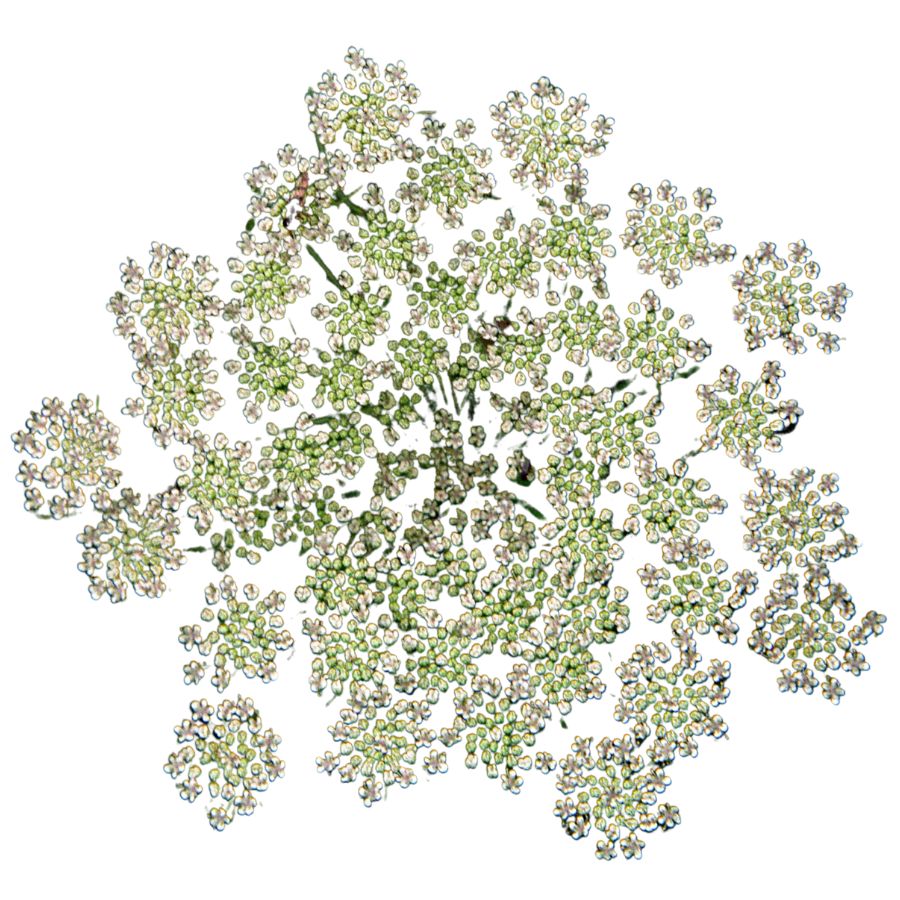

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | – Meadows and fields throughout Connecticut – Roadsides and open areas statewide – Gardens and disturbed soils in various regions |

| Spearmint (Mentha spicata) | – Stream banks and moist areas across the state – Wetlands and marshy regions in Connecticut – Gardens and damp soils statewide |

| Mountain Mint (Pycnanthemum virginianum) | – Meadows and fields in various regions – Edges of woodlands across Connecticut – Pollinator habitats and natural areas statewide |

| Sweet Goldenrod (Solidago odora) | – Meadows and open fields throughout Connecticut – Dry, sandy soils in various regions – Edges of woodlands statewide |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | – Clear, slow-moving streams across the state – Springs and freshwater seeps in Connecticut – Shallow water bodies and wetlands statewide |

| Cleavers (Galium aparine) | – Hedgerows and woodland edges throughout Connecticut – Moist, shaded areas in various regions – Gardens and disturbed soils statewide |

| Blackberry (Rubus allegheniensis) | – Forest edges and clearings across the state – Meadows and fields in various regions – Trailsides and open woodlands statewide |

| Raspberry (Rubus idaeus) | – Forest clearings and edges throughout Connecticut – Meadows and disturbed areas in various regions – Gardens and naturalized areas statewide |

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) | – Meadows and open fields across the state – Woodland clearings and edges in various regions – Lawns and grassy areas statewide |

| Wild Grape (Vitis labrusca) | – Forest edges and thickets throughout Connecticut – Fencerows and open woodlands in various regions – Along rivers and streams statewide |

| Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) | – Bogs and wetlands across the state – Acidic soils in forested areas throughout Connecticut – Meadows and open fields in various regions |

| Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) | – Moist meadows and fields across the state – Along streams and rivers in various regions – Wetlands and low-lying areas throughout Connecticut |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis) | – Forest understories and edges across the state – Meadows and open fields in various regions – Gardens and landscaped areas statewide |

| Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) | – Eisenhower Park, Milford – Black Rock State Park, Watertown – Bluff Point State Park, Groton |

| Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum) | – Housatonic Meadows State Park, Sharon – Pachaug State Forest, Voluntown – Sessions Woods WMA, Burlington |

| Wild Leek / Ramp (Allium tricoccum) | – Naugatuck State Forest, Beacon Falls – Mohawk State Forest, Cornwall – Macedonia Brook State Park, Kent |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | – Great Hill Conservation Area, Acton – Salmon River State Forest, Colchester – Devil’s Hopyard State Park, East Haddam |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | – Quinnipiac River State Park, North Haven – Farmington River Trail, Farmington – Hop River State Park Trail, Bolton |

| Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | – Black Sun Farm, Danielson – Housatonic River Walk, Cornwall – Sleeping Giant State Park, Hamden |

| Hickory (Carya ovata) | – Meshomasic State Forest, Portland – Cockaponset State Forest, Haddam – Nehantic State Forest, Lyme |

| Beech (Fagus grandifolia) | – Yale-Myers Forest, Union – Peoples State Forest, Barkhamsted – Tunxis State Forest, Hartland |

| American Hazelnut (Corylus americana) | – Barn Island WMA, Stonington – Mohegan State Forest, Scotland – Hurd State Park, East Hampton |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | – Wethersfield Cove, Wethersfield – Bantam Lake, Litchfield – Silver Sands State Park, Milford |

| Red Clover (Trifolium pratense) | – Haystack Mountain State Park, Norfolk – Bluff Point State Park, Groton – Topsmead State Forest, Litchfield |

| Common Violets (Viola sororia) | – Sherwood Island State Park, Westport – Rocky Neck State Park, East Lyme – Hammonasset Beach State Park, Madison |

| Wild Rose (Rosa carolina) | – Chatfield Hollow State Park, Killingworth – Bigelow Hollow State Park, Union – Harkness Memorial State Park, Waterford |

| Sweetfern (Comptonia peregrina) | – Pachaug State Forest, Voluntown – Natchaug State Forest, Eastford – Mount Tom State Park, Litchfield |

| Bee Balm (Monarda didyma) | – Kent Falls State Park, Kent – Devil’s Hopyard State Park, East Haddam – Gillette Castle State Park, East Haddam |

| Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) | – Community gardens in New Haven – Urban foraging areas in Hartford – Private gardens in Stamford |

| Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) | – Agricultural fields in Windsor – Community gardens in Bridgeport – Open fields in Cheshire |

| Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) | – Nipmuck State Forest, Union – Mohawk State Forest, Cornwall – Pachaug State Forest, Voluntown |

| Basswood (Tilia americana) | – Hurd State Park, East Hampton – Salmon River State Forest, Colchester – Tunxis State Forest, Hartland |

| Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara) | – Roadside areas in Litchfield County – Disturbed soils in Middlesex County – Abandoned fields in Windham County |

| Common Knotgrass (Polygonum aviculare) | – Trailsides in Fairfield County – Urban parks in New Haven – Open fields in Tolland County |

| Virginia Waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginianum) | – Rich woods in Litchfield County – Moist forests in Hartford County – Shaded areas in Middlesex County |

Peak Foraging Seasons

Different edible plants grow at different times of year, depending on the season and weather. Timing your search makes all the difference.

Spring

Spring brings a fresh wave of wild edible plants as the ground thaws and new growth begins:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara) | March – April | Early thaw, sunny open ground |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | March – May | Mild temperatures, recent rain, open sunny areas |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | March – May | Cool, moist, overcast or post-rain conditions |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | March – May | Damp, disturbed soils, moderate sun |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | March – May | Cool running water, overcast days |

| Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | April – June | Cool, damp weather, partly shaded woodland edges |

| Cleavers (Galium aparine) | April – June | Moist, shady spots after spring rains |

| Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) | April – May | Warm, moist soil, sunny stream banks |

| Wood Sorrel (Oxalis stricta) | April – May | Mild temps, light shade, recent moisture |

| Serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis) | April – May | Cool, stable weather during flowering |

| Wild Leek / Ramp (Allium tricoccum) | April – May | Cool, moist forest soil after spring rains |

| Common Violets (Viola sororia) | April – June | Mild temperatures, damp shaded meadows |

| Virginia Waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginianum) | April – May | Moist woods with cool spring temps |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | April – May | Shallow wetlands in warming spring weather |

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) | May | Sunny days after spring showers |

| Red Clover (Trifolium pratense) | May – June | Sunny fields after spring showers |

| Basswood (Tilia americana) | May – June | Warm, moist days during flowering |

Summer

Summer is a peak season for foraging, with fruits, flowers, and greens growing in full force:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Plantain (Plantago major) | June – August | Dry or moist soil, full or partial sun |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | June – August | Warm, dry days in sunny disturbed soil |

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | June – August | Hot, dry conditions, open fields |

| Spearmint (Mentha spicata) | June – August | Humid and sunny, moist soil |

| Bee Balm (Monarda didyma) | June – August | Sunny and humid woodland edges or fields |

| Sweetfern (Comptonia peregrina) | June – August | Dry, sunny conditions along sandy trails |

| Common Knotgrass (Polygonum aviculare) | June – August | Dry paths, compact soil, full sun |

| Red Clover (Trifolium pratense) | June – August | Warm, sunny meadows with scattered rain |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | June – August | Warm, standing water or marshy areas |

| Raspberries (Rubus idaeus) | June – July | Cool mornings, slight humidity |

| Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) | June – July | Moist garden soil after rains |

| Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) | July – August | Dry, sunny conditions in meadows |

| Mountain Mint (Pycnanthemum virginianum) | July – August | Warm and humid, semi-shade or open areas |

| Blackberries (Rubus allegheniensis) | July – August | Sunny days, after rain for plump fruit |

| Blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum) | July – August | Sunny and warm, well-drained acidic soil |

| Elderberries (Sambucus canadensis) | July – August | Humid, partially shaded areas near water |

| Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) | July – August | Hot, sunny days with well-drained soil |

| Sweet Goldenrod (Solidago odora) | August | Warm, dry weather in open sunny fields |

Fall

As temperatures drop, many edible plants shift underground or produce their last harvests:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | September | Dry fall days before frost |

| Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) | September | Cool, shaded areas after rainfall |

| Cleavers (Galium aparine) | September | Moist, shaded woods with stable temps |

| American Hazelnut (Corylus americana) | September | Dry days, just before or after nut release |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | September – October | Cool, damp days with moderate sun |

| Curly Dock (Rumex crispus) | September – October | Moist soil after rain, partly cloudy skies |

| Plantain (Plantago major) | September – October | Mild weather, early fall moisture |

| Wild Grape (Vitis labrusca) | September – October | Sunny days, cool nights for ripening |

| Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) | September – October | Sunny days, dry weather before frost |

| Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum) | September – October | Cool, crisp days near wetlands |

| Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) | September – October | Dry conditions during nut drop |

| Hickory (Carya ovata) | September – October | Clear fall days during nut fall |

| Wild Rose (Rosa carolina) | September – October | Cool, dry conditions for rose hip collection |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | September – November | Moist, cool conditions in shaded areas |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | September – November | Cool running water, no frost |

| Groundnut (Apios americana) | September – November | Moist soil after late summer rains |

| Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) | October – November | Cool ground, harvest before deep frost |

| Beech (Fagus grandifolia) | October – November | Breezy fall weather, leaf drop period |

Winter

Winter foraging is limited but still possible, with hardy plants and preserved growth holding on through the cold:

| Plant | Months | Best Weather Conditions |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | December – February (mild winters) | Unfrozen ground, mild winter thaws |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | December – February (mild winters) | Sunny winter days, unfrozen ground |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | December – February | Flowing unfrozen water, protected stream beds |

| Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) | December – February | Thawed ground between freezes |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | December – February | Ice edges or mild winter wetland access |

| Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) | December – February | Cold, snow-covered forest with exposed leaf litter |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.