Alaska is home to a range of edible plants that grow in places most people would never think to look. Some of them are hidden in plain sight, while others thrive in spots where conditions change by the hour. They’re not always easy to notice, but if you learn what to identify, you’ll start seeing how much there actually is.

Some plants are best picked fresh and eaten raw, while others need a little work before they’re safe or worth eating. A few are packed with flavor even in small amounts, and some have uses that go far beyond the kitchen.

There are edible plants here that are only around for a few days at a time and others that can be gathered well into the colder months.

It’s worth learning what to look for, because the variety can catch people off guard. Once you start recognizing them, it’s possible to go home with far more than you expected. Alaska’s edible plants offer more options than most realize, and it’s knowing which ones to gather that makes the difference.

What We Cover In This Article:

- The Edible Plants Found in the State

- Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

- How to Get the Best Results Foraging

- Where to Find Forageables in the State

- Peak Foraging Seasons

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

The Edible Plants Found in the State

Wild plants found across the state can add fresh, seasonal ingredients to your meals:

Fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium)

Tall and striking, fireweed showcases vibrant magenta flowers that bloom progressively up its stem throughout summer. The plant earned its name from being one of the first to colonize areas after forest fires.

Young shoots and leaves taste similar to asparagus when harvested in spring before they become tough and bitter. The flowers make a sweet, slightly spicy honey and delicious syrup.

Fireweed is easy to identify by its narrow, lance-shaped leaves with distinct veins and its tower of bright pink-purple flowers. No dangerous lookalikes exist, though evening primrose has similar leaves but yellow flowers.

The entire plant offers nutritional benefits. Leaves contain vitamins A and C, while the pith inside young stems can be eaten raw. Indigenous peoples traditionally used fireweed as both food and medicine to treat burns and inflammation.

Cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus)

Growing low to the ground in northern bogs and tundra, cloudberries resemble golden raspberries with their distinctive segmented appearance. These berries are treasured for their unique honey-like flavor with hints of apple and yogurt.

The edible part is the amber-colored berry that forms after the white flower fades. Cloudberries are packed with vitamin C and antioxidants, making them nutritionally valuable despite their scarcity.

Identification is straightforward once you know what to look for. The plant has large, maple-like leaves with 5-7 lobes and produces only one berry per stem.

Unlike other Rubus species, cloudberries aren’t thorny. They’re sometimes confused with salmonberries or thimbleberries, which are also edible but have different growth patterns and leaf shapes.

Wild Mint (Mentha arvensis)

You’re probably familiar with the strong scent of wild mint, which comes from the essential oils concentrated in its leaves. It has square stems, lance-shaped leaves with slightly toothed edges, and pale lilac flower clusters.

The fresh leaves can be eaten raw, cooked into soups, or muddled into drinks for a crisp flavor. Expect a bright, menthol-like kick with a hint of sweetness.

False mint species like purple deadnettle grow in similar spots but lack the menthol smell and have fuzzy leaves. If the plant doesn’t smell like mint, it probably isn’t.

Stick to the leaves and younger stems for eating because the woody stalks aren’t palatable. Wild mint also holds up well when dried and stored for tea or seasoning.

Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum edule)

Clusters of bright red berries dangling from woody shrubs signal the presence of highbush cranberry in forest edges and wet areas. Despite its name, this plant isn’t a true cranberry but belongs to the honeysuckle family.

The tart, acidic berries become sweeter after the first frost and make excellent jellies and sauces. Their high pectin content helps preserves set naturally without added thickeners.

Avoid confusing highbush cranberry with red elderberry, which has similar clusters but toxic berries growing on a different leaf pattern. Highbush cranberry leaves are three-lobed and maple-like, while elderberry leaves are compound with multiple leaflets.

Only the berries are edible, while stems, leaves, and seeds should be avoided. Indigenous peoples traditionally used the berries as both food and medicine. The berries maintain their vitamin C content well into winter when other food sources become scarce.

Alpine Sweetvetch (Hedysarum alpinum)

Delicate purple-pink flowers arranged along slender stems help identify this important northern plant in meadows and open forests. Alpine sweetvetch develops distinctive seed pods that hang like chains of flattened discs.

The underground roots, often called “Eskimo potatoes,” store carbohydrates and taste nutty and sweet when properly prepared. These roots were a staple food for many northern indigenous groups during lean winter months.

Be extremely careful when harvesting, as Alpine sweetvetch closely resembles poisonous wild loco plants. The key difference lies in the seed pods – sweetvetch pods have visible segments with constrictions between seeds, while toxic lookalikes have smooth pods.

Proper identification is crucial because eating the wrong plant can be fatal. The nutritious roots can be eaten raw, though cooking improves digestibility and flavor. Traditional knowledge suggests harvesting roots in fall when their sugar content peaks.

Goose Tongue (Plantago maritime)

Salty and succulent, goose tongue thrives in coastal areas where few plants can tolerate the harsh conditions. The fleshy, narrow leaves grow in basal rosettes close to the ground, resembling thick blades of grass.

The leaves offer a pleasant taste similar to salty green beans with a hint of mushroom umami. They’re most tender when young and become increasingly fibrous as they mature.

Goose tongue has no dangerous lookalikes in its coastal habitat, making it a safe choice for beginning foragers. The entire above-ground portion is edible and can be enjoyed raw in salads or cooked like spinach.

Rich in vitamins A and C, these nutritious greens have historically helped prevent scurvy among coastal peoples. The plant’s high salt content comes from its ability to filter seawater, making it a natural seasoning.

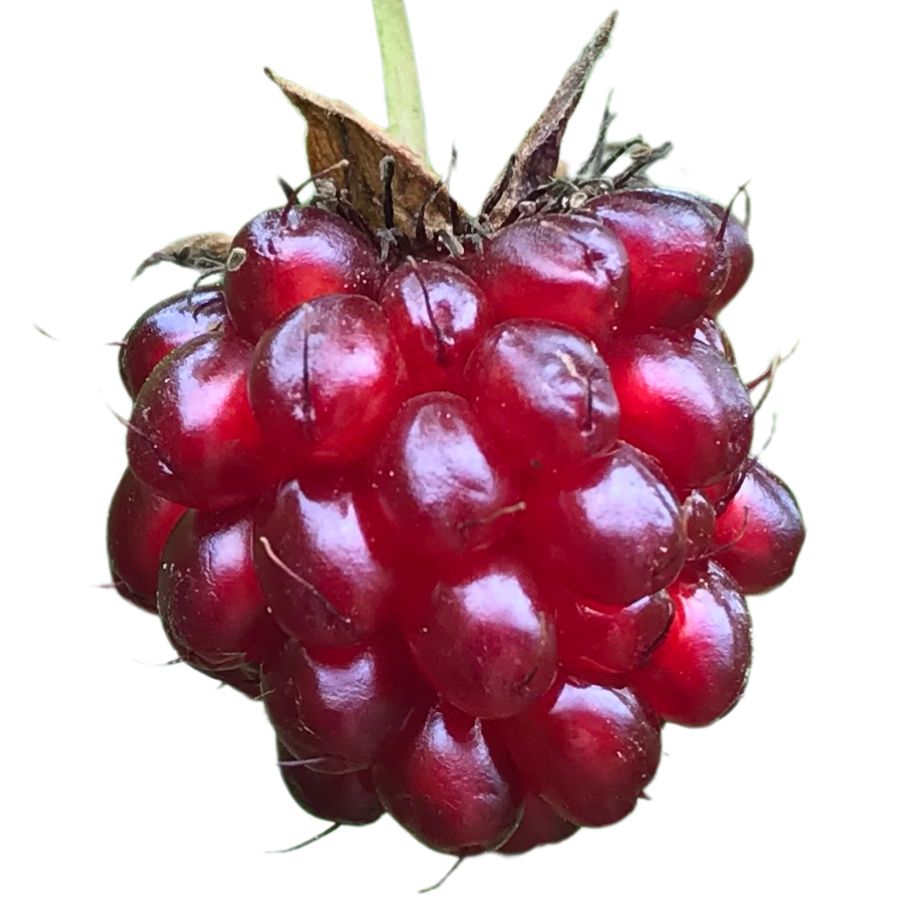

Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis)

Salmonberries are bright pink to red berries that are a sweet, tangy treat. They are similar to raspberries but have a firmer texture and a more pronounced sweetness with a slight tart finish.

Although the berries are safe to eat, it’s important to avoid consuming the leaves, as they can lead to mild stomach irritation. Keep an eye out for thimbleberry plants, which can look similar but have softer fruit and a distinctly different flavor profile.

Fresh salmonberries are often enjoyed on their own, mixed into yogurt, or turned into homemade preserves like jam. The fruit also freezes well, which allows you to enjoy the harvest long after picking.

Salmonberry bushes can be found along the edges of wetlands, and their thorns can make picking them a bit of a challenge. However, the effort is well worth it for those who enjoy the rich taste and versatility of this unique berry.

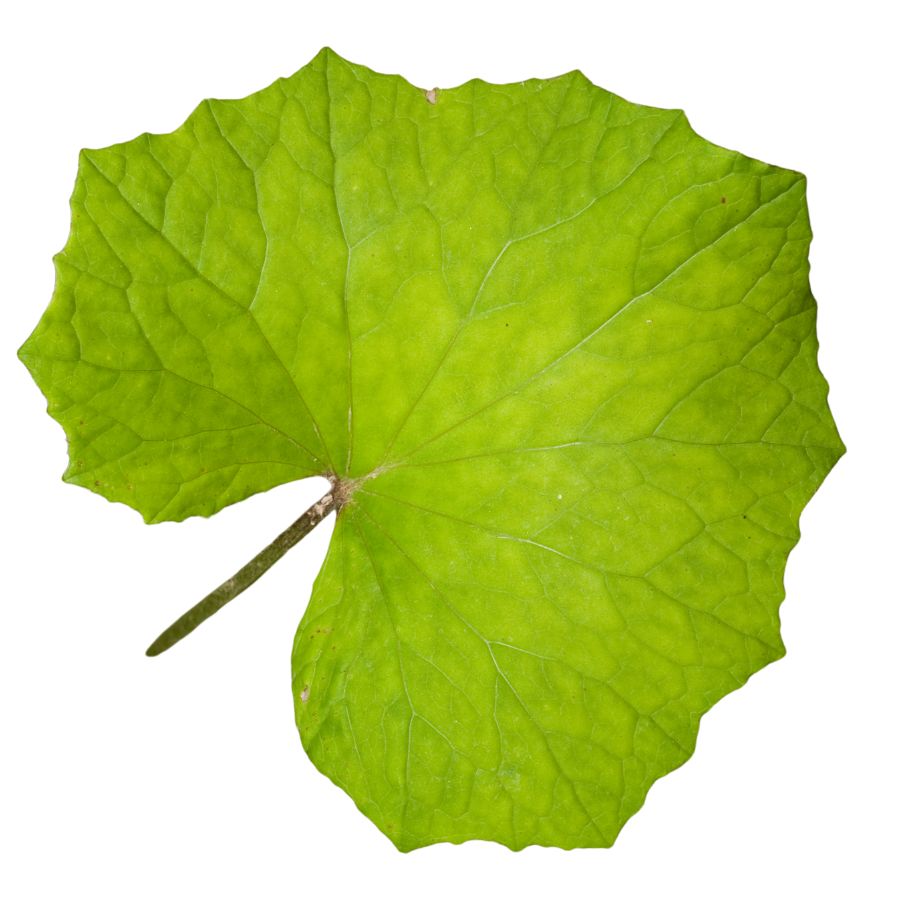

Sweet Coltsfoot (Petasites frigidus)

Sweet coltsfoot grows in damp areas with large heart-shaped leaves that can reach up to 12 inches across. The flowers appear before the leaves in early spring, showing off white to pink blossoms that resemble small daisies.

Only the young leaves and flower stalks are edible after proper preparation. The leaves contain small amounts of alkaloids that can be harmful to the liver if consumed in large quantities over time.

Sweet coltsfoot has a mild, slightly bitter flavor with hints of mint. Native peoples traditionally used it for treating coughs and respiratory issues.

When foraging, look for the distinctive hoof-shaped leaves with toothed edges and whitish undersides. The plant is sometimes confused with wild rhubarb, which has much larger leaves without the white underside. Sweet coltsfoot makes an interesting addition to spring soups when properly prepared.

Crowberry (Empetrum nigrum)

The tiny black berries of crowberry hang among needle-like evergreen leaves on low-growing shrubs across northern regions. These hardy plants form dense mats across the tundra, thriving in acidic soils where few other plants survive.

Crowberries are edible raw but have a mild, somewhat bland taste with slight bitterness. The true value comes from their incredible abundance in northern landscapes.

When identifying crowberry, look for the needle-like leaves arranged densely along stems and the small, round black fruits that resemble tiny blueberries. Unlike toxic black nightshade berries, crowberries grow on low evergreen shrubs rather than upright plants.

The berries can be eaten fresh, cooked into jams, or added to baked goods. They contain good levels of antioxidants and vitamin C. Indigenous peoples often mixed crowberries with other sweeter berries or animal fat to create pemmican for winter food storage.

Watercress (Nasturtium officinale)

Watercress, also known as yellowcress or garden cress, is an aquatic plant with small, rounded green leaves and hollow stems that often float along the water’s surface. It usually grows in dense mats, and the bright green color is one of the easiest ways to spot it in clear, shallow streams and ponds.

Besides being a popular edible green, watercress has been traditionally used in herbal remedies, especially for boosting digestion and respiratory health.

The leaves and stems are edible, offering a crisp texture and a peppery, slightly spicy taste that can remind you of arugula. People often enjoy it raw in salads, blended into soups, or lightly wilted into stir-fries for a fresh bite.

Stick to eating the leaves and stems, and avoid any parts that look yellowed or slimy, since healthy watercress should always look vibrant and clean.

Watercress has a few lookalikes like lesser celandine or young wild mustard, but true watercress has a distinct sharp flavor and tends to grow only in moving, clean water. Always double-check your identification, because gathering from stagnant or contaminated water sources can expose you to harmful bacteria or parasites.

Wild Onion (Allium schoenoprasum)

Wild onion, sometimes called meadow garlic or wild garlic, grows with slender green stems and small bulbs tucked just below the surface. The leaves are smooth, narrow, and hollow, giving off a sharp onion scent when crushed between your fingers.

The entire plant is edible, from the crisp bulbs to the tender stems and flowers. Its strong onion flavor can be used fresh, cooked into soups, or even pickled for longer storage.

One important thing to watch for is its lookalike, death camas, which has similar leaves but no onion smell and can be deadly if eaten. Always crush a leaf and check for that familiar onion scent before harvesting any wild onion.

Wild onion adds a punch of flavor to dishes like scrambled eggs, roasted meats, and vegetable sautés. Besides cooking, it has a long history of being used in herbal remedies for colds and minor infections.

Spruce Tips (Picea spp.)

Bright green and tender, spruce tips emerge at the ends of branches in spring, offering a burst of citrusy flavor with notes of resin. These new growths are soft and distinctly different from the mature sharp needles found on the rest of the tree.

Spruce tips have high vitamin C content, which made them valuable to indigenous peoples and early explorers as a scurvy preventative. They can be identified by their light green color and soft texture compared to the darker, firmer mature needles.

When harvesting, take only a few tips from each branch to avoid harming the tree’s growth. Never confuse spruce with yew trees, which have flat needles and are toxic.

The young tips can be used to make tea, syrup, or even spruce tip jelly. Some creative cooks use them to flavor ice cream or beer. Their unique flavor adds a wild, forest essence to many dishes.

Sea Lovage (Ligusticum scoticum)

Along rocky coastlines, sea lovage stands out with its glossy, celery-like leaves and robust growth despite harsh ocean winds. This maritime plant has a powerful aroma that combines celery with hints of parsley and a touch of ocean saltiness.

The leaves, stems, and seeds of sea lovage are all edible and pack a strong flavor punch. When identifying this coastal treasure, look for the distinctive three-part compound leaves and the plant’s preference for growing just above the high tide line.

Sea lovage can be confused with water hemlock, a deadly poisonous plant. However, water hemlock lacks the distinctive celery smell and typically grows in freshwater areas rather than coastal environments.

Traditional coastal communities have used sea lovage as both food and medicine for generations. The leaves make an excellent seasoning for fish dishes, while the stems can be candied like angelica. Its strong flavor means a little goes a long way in cooking.

Arctic Raspberry (Rubus arcticus)

A single delicate pink flower adorns each stem of the arctic raspberry, eventually developing into a ruby-red berry treasured for its intense flavor. Unlike its taller raspberry relatives, this plant grows close to the ground in northern forests and tundra.

Arctic raspberry fruits are smaller than commercial varieties but offer an amazingly complex flavor profile that many describe as superior to common raspberries. The taste combines raspberry, honey, and unique floral notes.

These plants form small patches rather than dense thickets. Look for the distinctive three-leaflet pattern and low growth habit when identifying them. Unlike some other Rubus species, arctic raspberries have no thorns, making them easier to harvest.

The berries are perfectly safe to eat raw and are traditionally collected for special occasions due to their scarcity and extraordinary flavor. They spoil quickly after picking and don’t transport well, making them a true forager’s prize that few people outside northern regions have experienced.

Beach Pea (Lathyrus japonicus)

Purple-blue flowers that resemble sweet peas mark this coastal plant forming sprawling vines along sandy shores. Beach Pea develops an extensive root system that helps stabilize shorelines where few other plants survive.

The young pods and peas are edible when properly prepared. However, they should never be eaten raw or in large quantities as they contain low levels of toxins that are destroyed through thorough cooking.

Beach Pea has historically served as emergency food during famines in coastal regions. The tender shoots and young leaves can also be consumed in moderation after cooking.

Unlike garden peas, it has a more earthy, slightly bitter flavor. The pods should be harvested while still young and flexible. Mature seeds should be avoided as they contain higher concentrations of toxins than young pods.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

Bright yellow flowers and jagged, deeply toothed leaves make dandelions easy to spot in open fields, lawns, and roadsides. You might also hear them called lion’s tooth, blowball, or puffball once the flowers turn into round, white seed heads.

Every part of the dandelion is edible, but you will want to avoid harvesting from places treated with pesticides or roadside areas with heavy car traffic. Besides being a food source, dandelions have been used traditionally for simple herbal remedies and natural dye projects.

Young dandelion leaves have a slightly bitter, peppery flavor that works well in salads or sautés, and the flowers can be fried into fritters or brewed into tea. Some people even roast the roots to make a coffee substitute with a rich, earthy taste.

One thing to watch out for is cat’s ear, a common lookalike with hairy leaves and branching flower stems instead of a single, hollow one. To make sure you have a true dandelion, check for a smooth, hairless stem that oozes a milky sap when broken.

Cattail (Typha latifolia)

Cattails, often called bulrushes or corn dog grass, are easy to spot with their tall green stalks and brown, sausage-shaped flower heads. They grow thickly along the edges of ponds, lakes, and marshes, forming dense stands that are hard to miss.

Almost every part of the cattail is edible, including the young shoots, flower heads, and starchy rhizomes. You can eat the tender shoots raw, boil the flower heads like corn on the cob, or grind the rhizomes into flour for baking.

Besides food, cattails have long been used for making mats, baskets, and even insulation by weaving the dried leaves and using the fluffy seeds. Their combination of usefulness and abundance has made them an important survival plant for many cultures.

One thing you need to watch for is young cattail shoots being confused with similar-looking plants like iris, which are toxic. A real cattail shoot will have a mild cucumber-like smell when you snap it open, while iris plants smell bitter or unpleasant.

Plantain (Plantago major)

Plantain, also called common plantain or narrowleaf plantain depending on the type, is a low-growing plant with broad or lance-shaped leaves and tall, slender flower spikes. The leaves grow in a rosette close to the ground, and the thick veins running through them are one of the easiest ways to tell it apart from other plants.

You can mainly eat the young leaves and the seeds of the plants. Older leaves can become tough and stringy, so it is best to pick the smaller, tender ones when you want to eat them.

Plantain leaves have a slightly bitter, earthy taste and a chewy texture, especially when eaten raw. Many people like to add them to salads, soups, or stews, or lightly steam them to soften the flavor.

Always make sure you have a true plantain before eating because some similar-looking yard plants are not palatable and can upset your stomach. Look for the strong parallel veins and the tough, fibrous stems to help confirm your find.

Prickly Rose (Rosa acicularis)

Native to northern forests, Prickly Rose displays delicate pink flowers that adorn its thorny stems. This hardy shrub grows up to 3 feet tall, with five-petaled blooms that transform into bright red fruits called rose hips.

The rose hips are the prized edible portion, containing more vitamin C than oranges. They can be harvested after the first frost when they become slightly soft and sweeter.

Identification is straightforward with the plant’s prickly stems and distinctive rose-like flowers. No dangerous lookalikes exist, though other wild roses are also edible, but may have different flavors.

Rose hips make excellent jams, teas, and syrups. Remove the tiny hairs and seeds inside before consuming as they can irritate the digestive tract. The petals are also edible and add a gentle floral note to salads and desserts.

Fiddlehead Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris)

Tightly coiled like the scroll of a violin, these young shoots of Ostrich Fern emerge in clusters from the forest floor. If left unharvested, they unfurl into large feathery fronds that can reach several feet in height.

A key identifying feature is the deep U-shaped groove on the inside of the smooth stem. Fiddleheads must never be consumed raw as they contain compounds that can cause illness.

Beware of false fiddleheads from other fern species which may be toxic. Proper identification is crucial as only Ostrich Fern fiddleheads are safely edible.

The flavor resembles a blend of asparagus, green beans, and nuts. Harvest when they are small, still tightly coiled, and covered with brown papery scales. Cook thoroughly by boiling for at least 10 minutes or steaming for 20 minutes before enjoying.

Toxic Plants That Look Like Edible Plants

There are plenty of wild edibles to choose from, but some toxic native plants closely resemble them. Mistaking the wrong one can lead to severe illness or even death, so it’s important to know exactly what you’re picking.

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild carrot (Daucus carota)

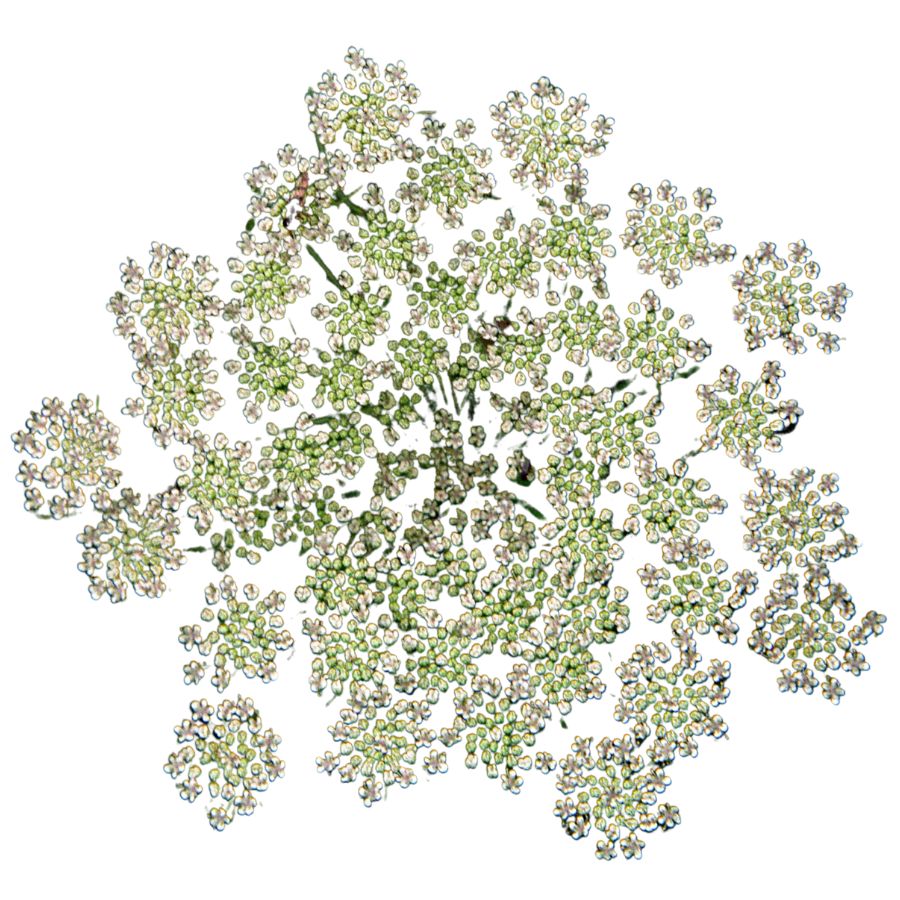

Poison hemlock is a tall plant with lacy leaves and umbrella-like clusters of tiny white flowers. It has smooth, hollow stems with purple blotches and grows in sunny places like roadsides, meadows, and stream banks.

Unlike wild carrot, which has hairy stems and a dark central floret, poison hemlock has a musty odor and no flower center spot. It’s extremely toxic; just a small amount can be fatal, and even touching the sap can irritate the skin.

Water Hemlock (Cicuta spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) or wild celery (Apium spp.)

Water hemlock is a tall, branching plant with umbrella-shaped clusters of small white flowers. It grows in wet places like stream banks, marshes, and ditches, with stems that often show purple streaks or spots.

It can be confused with wild parsnip or wild celery, but its thick, hollow roots have internal chambers and release a yellow, foul-smelling sap when cut. Water hemlock is the most toxic plant in North America, and just a small amount can cause seizures, respiratory failure, and death.

False Hellebore (Veratrum viride)

Often mistaken for: Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

False hellebore is a tall plant with broad, pleated green leaves that grow in a spiral from the base, often appearing early in spring. It grows in moist woods, meadows, and along streams.

It’s commonly mistaken for ramps, but ramps have a strong onion or garlic smell, while false hellebore is odorless and later grows a tall flower stalk. The plant is highly toxic, and eating any part can cause nausea, a slowed heart rate, and even death due to its alkaloids that affect the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Death Camas (Zigadenus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Wild onion or wild garlic (Allium spp.)

Death camas is a slender, grass-like plant that grows from underground bulbs and is found in open woods, meadows, and grassy hillsides. It has small, cream-colored flowers in loose clusters atop a tall stalk.

It’s often confused with wild onion or wild garlic due to their similar narrow leaves and habitats, but only Allium plants have a strong onion or garlic scent, while death camas has none. The plant is extremely poisonous, especially the bulbs, and even a small amount can cause nausea, vomiting, a slowed heartbeat, and potentially fatal respiratory failure.

Buckthorn Berries (Rhamnus spp.)

Often mistaken for: Elderberries (Sambucus spp.)

Buckthorn is a shrub or small tree often found along woodland edges, roadsides, and disturbed areas. It produces small, round berries that ripen to dark purple or black and usually grow in loose clusters.

These berries are sometimes mistaken for elderberries and other wild fruits, which also grow in dark clusters, but elderberries form flat-topped clusters on reddish stems while buckthorn berries are more scattered. Buckthorn berries are unsafe to eat as they contain compounds that can cause cramping, vomiting, and diarrhea, and large amounts may lead to dehydration and serious digestive problems.

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Mayapple is a low-growing plant found in shady forests and woodland clearings. It has large, umbrella-like leaves and produces a single pale fruit hidden beneath the foliage.

The unripe fruit resembles a small green grape, causing confusion with wild grapes, which grow in woody clusters on vines. All parts of the mayapple are toxic except the fully ripe, yellow fruit, which is only safe in small amounts. Eating unripe fruit or other parts can lead to nausea, vomiting, and severe dehydration.

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Often mistaken for: Wild grapes (Vitis spp.)

Virginia creeper is a fast-growing vine found on fences, trees, and forest edges. It has five leaflets per stem and produces small, bluish-purple berries from late summer to fall.

It’s often confused with wild grapes since both are climbing vines with similar berries, but grapevines have large, lobed single leaves and tighter fruit clusters. Virginia creeper’s berries are toxic to humans and contain oxalate crystals that can cause nausea, vomiting, and throat irritation.

Castor Bean (Ricinus communis)

Often mistaken for: Wild rhubarb (Rumex spp. or Rheum spp.)

Castor bean is a bold plant with large, lobed leaves and tall red or green stalks, often found in gardens, along roadsides, and in disturbed areas in warmer regions in the US. Its red-tinged stems and overall size can resemble wild rhubarb to the untrained eye.

Unlike rhubarb, castor bean plants produce spiny seed pods containing glossy, mottled seeds that are extremely toxic. These seeds contain ricin, a deadly compound even in small amounts. While all parts of the plant are toxic, the seeds are especially dangerous and should never be handled or ingested.

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification of mushrooms can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming mushrooms, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild mushrooms involves inherent risks.

How to Get the Best Results Foraging

Safety should always come first when it comes to foraging. Whether you’re in a rural forest or a suburban greenbelt, knowing how to harvest wild foods properly is a key part of staying safe and respectful in the field.

Always Confirm Plant ID Before You Harvest Anything

Knowing exactly what you’re picking is the most important part of safe foraging. Some edible plants have nearly identical toxic lookalikes, and a wrong guess can make you seriously sick.

Use more than one reliable source to confirm your ID, like field guides, apps, and trusted websites. Pay close attention to small details. Things like leaf shape, stem texture, and how the flowers or fruits are arranged all matter.

Not All Edible Plants Are Safe to Eat Whole

Just because a plant is edible doesn’t mean every part of it is safe. Some plants have leaves, stems, or seeds that can be toxic if eaten raw or prepared the wrong way.

For example, pokeweed is only safe when young and properly cooked, while elderberries need to be heated before eating. Rhubarb stems are fine, but the leaves are poisonous. Always look up which parts are edible and how they should be handled.

Avoid Foraging in Polluted or Contaminated Areas

Where you forage matters just as much as what you pick. Plants growing near roads, buildings, or farmland might be coated in chemicals or growing in polluted soil.

Even safe plants can take in harmful substances from the air, water, or ground. Stick to clean, natural areas like forests, local parks that allow foraging, or your own yard when possible.

Don’t Harvest More Than What You Need

When you forage, take only what you plan to use. Overharvesting can hurt local plant populations and reduce future growth in that area.

Leaving plenty behind helps plants reproduce and supports wildlife that depends on them. It also ensures other foragers have a chance to enjoy the same resources.

Protect Yourself and Your Finds with Proper Foraging Gear

Having the right tools makes foraging easier and safer. Gloves protect your hands from irritants like stinging nettle, and a good knife or scissors lets you harvest cleanly without damaging the plant.

Use a basket or breathable bag to carry what you collect. Plastic bags hold too much moisture and can cause your greens to spoil before you get home.

This forager’s toolkit covers the essentials for any level of experience.

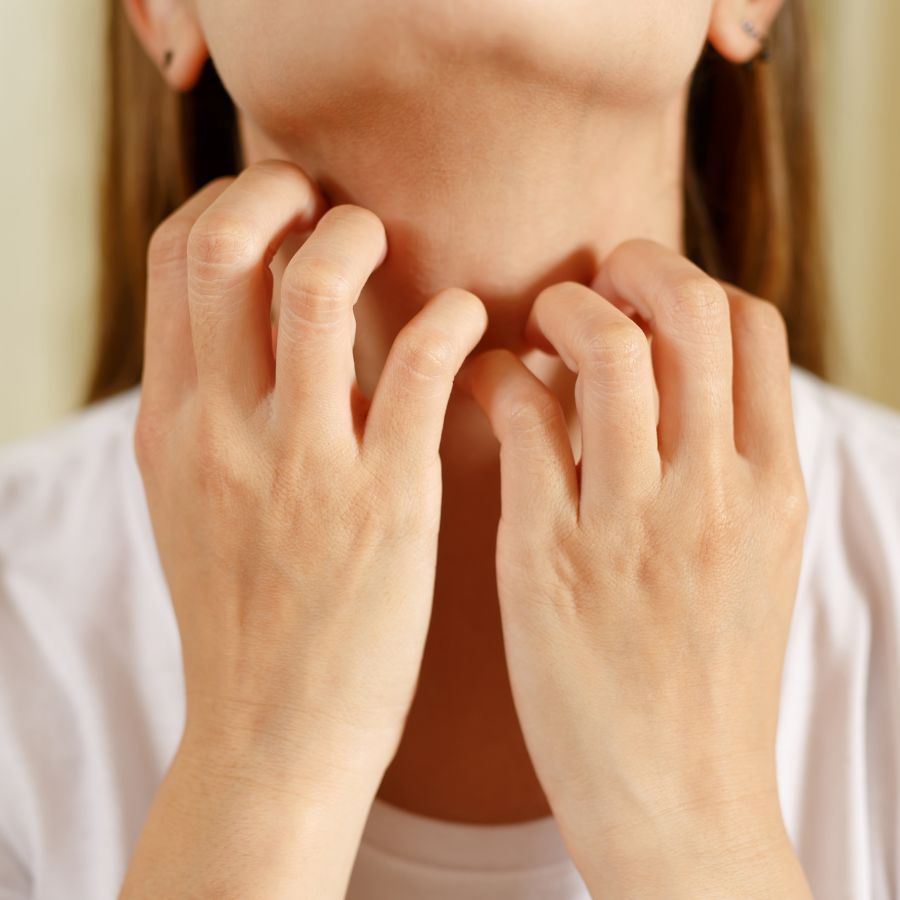

Watch for Allergic Reactions When Trying New Wild Foods

Even if a wild plant is safe to eat, your body might react to it in unexpected ways. It’s best to try a small amount first and wait to see how you feel.

Be extra careful with kids or anyone who has allergies. A plant that’s harmless for one person could cause a reaction in someone else.

Check Local Rules Before Foraging on Any Land

Before you start foraging, make sure you know the rules for the area you’re in. What’s allowed in one spot might be completely off-limits just a few miles away.

Some public lands permit limited foraging, while others, like national parks, usually don’t allow it at all. If you’re on private property, always get permission first.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

Where to Find Forageables in the State

There is a range of foraging spots where edible plants grow naturally and often in abundance:

| Plant | Locations |

|---|---|

| Fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium) | – Chugach State Park – Kenai Peninsula near Soldotna – Denali Highway corridor |

| Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum edule) | – Kincaid Park, Anchorage – Matanuska Greenbelt – Eagle River Nature Center |

| Lowbush Cranberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) | – Hatcher Pass – Petersville Road area – Togiak National Wildlife Refuge |

| Bog Blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum) | – Nome Creek Valley – Delta Junction wetlands – Kenai National Wildlife Refuge |

| Alpine Blueberry (Vaccinium ovalifolium) | – Portage Pass Trail – Glacier View area – Wrangell Mountains foothills |

| Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis) | – Juneau Rainforest Trails – Ketchikan Creek – Hollis on Prince of Wales Island |

| Cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus) | – Bethel area tundra – Dillingham flats – Yukon Delta wetlands |

| Nagoonberry (Rubus arcticus) | – Cordova coastal meadows – Kodiak Island trails – Haines State Forest |

| Crowberry (Empetrum nigrum) | – Barrow coastal plains – Cape Krusenstern National Monument – Kobuk Valley hills |

| Red Currant (Ribes triste) | – Fairbanks greenbelts – Tanana River floodplain – Richardson Highway pullouts |

| Black Currant (Ribes hudsonianum) | – Chena River SRA – North Pole woodlands – Lake Louise area |

| Northern Red Raspberry (Rubus idaeus strigosus) | – Seward highway slopes – Palmer Hay Flats – Tok Cut-Off region |

| Prickly Rose (Rosa acicularis) | – Turnagain Arm trail system – Copper Center – Nome coastal forests |

| Labrador Tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum) | – Selawik NWR – Tanana Flats – Glennallen wetlands |

| Wild Mint (Mentha arvensis) | – Yentna River banks – Koyukuk River valley – Sitka wet edges |

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | – Palmer lawns and trails – Eielson AFB surroundings – Baranof Island edges |

| Beach Greens (Ligusticum scoticum) | – Seldovia beaches – Homer Spit tidal area – Craig coastline |

| Beach Pea (Lathyrus japonicus) | – Nome beach trails – Yakutat coast – Dutch Harbor dunes |

| Wild Celery (Angelica lucida) | – Juneau shoreline – Kodiak coastal ridges – Unalaska bluff edges |

| Sweet Coltsfoot (Petasites frigidus) | – Talkeetna forest edges – Valdez creek lines – Lake Clark foothills |

| Cattail (Typha latifolia) | – Potter Marsh – Minto Flats – Wasilla Lake wetlands |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | – Anchorage greenbelts – Kenai River flats – Sitka neighborhood trails |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | – Bethel road edges – Anchorage lawns – Homer trail systems |

| Plantain (Plantago major) | – Fairbanks bike paths – Kodiak yards – Nome roadside areas |

| Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) | – Palmer farmland – Delta Junction fields – Tok roadside areas |

| Sorrel (Rumex acetosa) | – Chugach National Forest – Tanana Valley meadows – Skagway alpine edges |

| Wild Onion (Allium schoenoprasum) | – Denali Park lowlands – McCarthy meadows – Barrow gravel bars |

| Fiddlehead Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) | – Juneau riverbanks – Southeast rainforest gullies – Sitka wet trails |

| Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) | – Spring Creek near Seward – Juneau freshwater springs – Nome stream banks |

| Goose Tongue (Plantago maritima) | – Valdez tidal areas – Kachemak Bay marsh edges – Point Hope coast |

| Marsh Marigold (Caltha palustris) | – Yukon Flats – Southeast sloughs – Copper River Delta |

| Wild Rhubarb (Rumex arcticus) | – Kobuk River trails – Nome tundra – King Salmon outskirts |

| Arctic Dock (Rumex arcticus) | – Utqiaġvik meadows – Bristol Bay flats – Galena trail areas |

| Wild Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis) | – Palmer field margins – Delta lakeshore edges – Kodiak abandoned gardens |

| Northern Bedstraw (Galium boreale) | – Tanana Hills – Chena Hot Springs area – Fort Yukon trails |

| Alpine Sweetvetch (Hedysarum alpinum) | – Anaktuvuk Pass – Brooks Range valleys – Kotzebue surroundings |

| Wild Parsnip (Heracleum lanatum) | – Fairbanks sloughs – Talkeetna River forest – Homer field edges |

| Willow (Salix spp.) | – Nenana riverbanks – Chugach foothills – Selawik lowlands |

| Devil’s Club (Oplopanax horridus) | – Tongass National Forest – Juneau trails – Yakutat forest understory |

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) | – Haines hillside meadows – Valdez picnic grounds – Seward forest openings |

| Cow Parsnip (Heracleum maximum) | – Kodiak coastal flats – Denali Highway ditches – Ketchikan rainforest paths |

| Birch (Betula spp.) | – Interior river valleys – Copper River Basin – Tanana uplands |

| Spruce Tips (Picea spp.) | – Healy spruce forests – Chugach backcountry – Ketchikan trails |

| Pine (Pinus spp.) | – Fort Richardson area – Haines pine ridges – Tok forest groves |

| Horsetail (Equisetum arvense) | – Mendenhall Glacier wetlands – Bethel lowland trails – Cooper Landing streams |

| Arctic Raspberry (Rubus arcticus) | – Barrow coastal tundra – Kobuk River delta – Deadhorse shrublands |

| Sea Sandwort (Honckenya peploides) | – Ninilchik beach edge – Saint Paul Island coast – Shishmaref dunes |

Peak Foraging Seasons

Different edible plants grow at different times of year, depending on the season and weather. Timing your search makes all the difference.

Spring

Spring brings a fresh wave of wild edible plants as the ground thaws and new growth begins:

| Plant | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Fiddlehead fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) | April–May | Damp, shady forest edges near streams |

| Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | March–May | Sunny days after light rain on disturbed soils |

| Chickweed (Stellaria media) | March–May | Cool, moist ground in partial shade |

| Plantain (Plantago major) | April–May | Moist trailsides and grassy openings |

| Wild onion (Allium schoenoprasum) | April–May | Open meadows with moist, well-drained soil |

| Lamb’s quarters (Chenopodium album) | May | Sunny disturbed soils with loose earth |

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | May | Dry, sunny fields or roadsides |

| Sorrel (Rumex acetosa) | April–May | Moist, partly shaded alpine meadows |

| Sweet coltsfoot (Petasites frigidus) | April–May | Wet ditches and along forest streams |

| Arctic dock (Rumex arcticus) | May | Moist tundra areas after snowmelt |

Summer

Summer is a peak season for foraging, with fruits, flowers, and greens growing in full force:

| Plant | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium) | June–August | Sunny meadows and burned areas |

| Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis) | July–August | Moist forest clearings after warm days |

| Cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus) | July–August | Peat bogs under partly sunny skies |

| Highbush cranberry (Viburnum edule) | July–August | Damp forest understory during mild weather |

| Blueberries (Vaccinium uliginosum, V. ovalifolium) | July–August | Sunny alpine slopes with some moisture |

| Lowbush cranberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) | August | Cool, damp evergreen forests |

| Nagoonberry (Rubus arcticus) | July | Sunny lowland bogs and meadows |

| Red currant (Ribes triste) | July–August | Moist forest edges on overcast mornings |

| Goose tongue (Plantago maritima) | June–August | Salty tidal flats during low tide |

| Sea sandwort (Honckenya peploides) | June–July | Coastal dunes on mild, breezy days |

| Cow parsnip (Heracleum maximum) | June–July | Moist forest openings and riverbanks |

| Wild mint (Mentha arvensis) | July–August | Near streambanks on humid days |

| Wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) | June–July | Sunny hillsides and forest margins |

| Wild celery (Angelica lucida) | July–August | Coastal ridges with sea spray exposure |

| Wild rose (Rosa acicularis) – petals | June–July | Open forests and fields on sunny mornings |

| Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum) | June–August | Peat bogs and muskegs under cloudy skies |

| Beach greens (Ligusticum scoticum) | July–August | Coastal cliff edges with salty wind |

| Alpine sweetvetch (Hedysarum alpinum) | July–August | Rocky slopes during dry, sunny weather |

Fall

As temperatures drop, many edible plants shift underground or produce their last harvests:

| Plant | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Highbush cranberry (Viburnum edule) | September | After first frost in shady woods |

| Lowbush cranberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) | September–October | Cold evergreen thickets before snowfall |

| Crowberry (Empetrum nigrum) | September | Windswept tundra with cold but dry air |

| Wild rose (Rosa acicularis) – hips | September–October | Open fields and forest edges after frost |

| Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) | September | Riverbanks with crisp air and sun |

| Red currant (Ribes triste) | September | Moist woods under cloudy skies |

| Marsh marigold (Caltha palustris) – seeds | September | Along quiet creeks before freeze-up |

| Wild rhubarb (Rumex arcticus) – stems | September | Tundra flats after leaf fall |

| Willow (Salix spp.) – inner bark | October–November | Near water during early frost |

| Birch (Betula spp.) – inner bark | September–October | River valleys before snow accumulation |

Winter

Winter foraging is limited but still possible, with hardy plants and preserved growth holding on through the cold:

| Plant | Months | Best weather conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Birch (Betula spp.) – inner bark | December–February | During thaws in low-snow forests |

| Willow (Salix spp.) – inner bark | December–February | Frozen streambeds in still air |

| Spruce tips (Picea spp.) – buds | February | Sunny slopes after mid-winter thaws |

| Pine (Pinus spp.) – needles | December–February | Evergreen stands during cold, dry spells |

| Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum) – dried leaves | February | Muskegs with minimal snow cover |

| Devil’s club (Oplopanax horridus) – inner bark | January–February | Snowy forest floor near seeps |

| Horsetail (Equisetum arvense) – dried shoots | February | Sandy banks during melt periods |

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.