Hunting for chanterelle mushrooms in Pennsylvania means searching for one of the state’s most prized wild edibles. These mushrooms stand out with their golden color, fruity aroma, and meaty texture that holds up in any skillet.

Chanterelles are part of a long human tradition, with archaeological finds showing they’ve been foraged and eaten for thousands of years. In Pennsylvania’s woodlands, they remain a favorite among foragers who know how to spot their signature shape hiding under leaf litter.

It takes more than luck to come home with a good haul. Knowing which types of places chanterelles favor can open the door to finding not just one patch but a whole variety of wild mushrooms. Some of the best spots in the state are ones most people walk right past without realizing what’s beneath their feet.

What We Cover In This Article:

- What Chanterelle Mushrooms Look Like

- Mushrooms That Look Like Chanterelles But Aren’t

- How to Find Chanterelles

- Where You Can Find Chanterelles

- Additional Locations to Find Chanterelles

- When You Can Find Chanterelles

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

What Chanterelle Mushrooms Look Like

Chanterelles are among the most popular wild edible mushrooms in North America. Here are some of the main types of chanterelles found across different regions of the country:

Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius group)

Golden chanterelles are one of the most recognizable wild mushrooms, with bright yellow to deep orange caps shaped like trumpets. They have thick, wavy edges and shallow ridges underneath instead of true gills.

These mushrooms are known for their fruity, apricot-like scent and a rich, nutty flavor when cooked. They grow in hardwood forests across the eastern, central, and southern United States, often near oaks, beech, or birch trees in late summer through fall.

Pacific Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus formosus)

The Pacific golden chanterelle has a bright orange cap with a flared, uneven shape and shallow, blunt ridges underneath. Its sturdy stem is usually pale to light yellow, and the whole mushroom has a smooth, velvety feel.

It has a mild, nutty taste with a hint of fruitiness when cooked. These mushrooms are mostly found in the damp forests of Oregon, Washington, and northern California, often growing under Douglas fir and other conifers in fall and early winter.

White Chanterelle (Cantharellus subalbidus)

White chanterelles are large, heavy mushrooms with a smooth, off-white cap that can look almost golden after rain. The stem is thick and solid, and the surface may feel slightly waxy when fresh.

They have a subtle earthy taste with a gentle, fruity smell that gets stronger in the pan. These mushrooms grow in moist conifer forests along the West Coast, especially in Oregon and northern California, often hiding under thick layers of fir needles.

Smooth Chanterelle (Cantharellus lateritius)

The smooth chanterelle has a soft orange to pale yellow cap with an almost completely smooth underside instead of well-defined ridges. Its cap often blends right into the stem, giving it a rounded, seamless appearance.

It has a mild, slightly peppery flavor and a firm texture when cooked. This mushroom is common in the eastern and southeastern United States, especially in hardwood forests with oak and beech during warm summer months.

Red Chanterelle (Cantharellus cinnabarinus)

Red chanterelles are easy to spot thanks to their vivid coral to crimson coloring and compact size. They have a smooth, wavy cap with soft ridges that flow down a short, sturdy stem.

Their taste is delicate and slightly sweet, with a faint fruity smell when fresh. These mushrooms grow in leaf litter across eastern and southeastern forests, often appearing in large groups during warm, wet periods in summer.

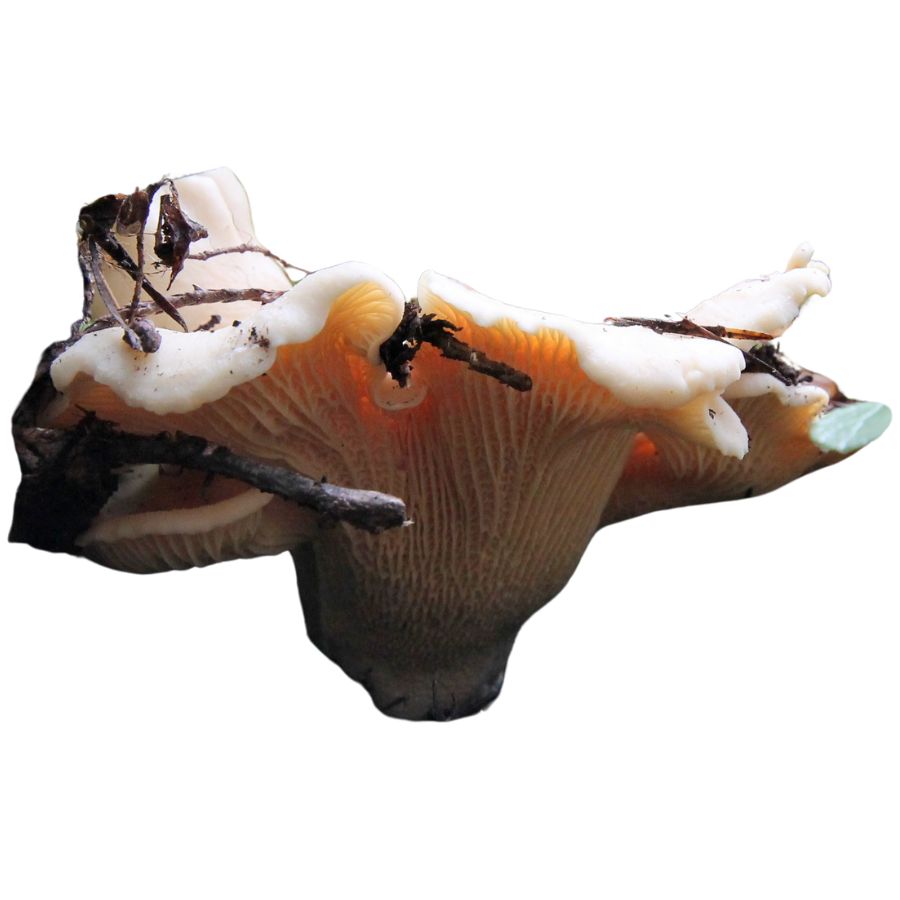

Mushrooms That Look Like Chanterelles But Aren’t

Chanterelles have several lookalikes that can confuse even experienced foragers. This is why learning to recognize easy-to-identify wild mushrooms is one of the most important skills for any mushroom hunter. Below are a few mushrooms often mistaken for chanterelles, with details on how to tell them apart.

False Chanterelle (Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca)

The false chanterelle has a bright orange to orange-brown cap with a fuzzy surface and rolled-in edges. Its gills are thin, crowded, and more regular than true chanterelles.

This mushroom shows up in many parts of the U.S., especially in conifer forests of the Pacific Northwest, the Northeast, and the Southeast. It prefers mossy or needle-covered forest floors and often grows on decaying wood.

While not dangerously toxic, it can cause stomach upset and isn’t considered a good edible. Its bitter taste and texture make it unappealing.

Jack-o’-Lantern Mushroom (Omphalotus illudens, Omphalotus olearius, Omphalotus subilludens)

These mushrooms are often bright orange, grow in clusters, and have true gills that run down the stem. They are best known for their eerie greenish glow at night due to bioluminescence.

Jack-o’-lantern mushrooms are found in hardwood forests throughout the eastern U.S., the Midwest, the Gulf Coast, and parts of California. They typically grow on decaying stumps or buried wood.

All three species are poisonous and can cause severe vomiting, cramps, and diarrhea. They should never be eaten under any circumstances.

Scaly Vase Chanterelle (Turbinellus floccosus)

This mushroom has a thick, vase-like shape with a scaly orange to brownish cap and ridged, wrinkled undersides. Unlike chanterelles, it has a tough texture and a strong, unpleasant odor when mature.

It’s widespread in western states like California, Oregon, and Washington, especially in conifer-heavy mountain forests. Scaly vase chanterelles often grow near pines or firs and appear in summer through fall.

While not deadly, they can cause nausea and gastrointestinal issues and are not considered edible. Their coarse texture and poor flavor also make them undesirable.

Orange Mock Chanterelle (Gomphus clavatus, sometimes called Pig’s Ears)

Despite its nickname, this mushroom is shaped more like a funnel or ear than a true chanterelle. Its surface is wrinkled rather than gilled, and the color ranges from lavender-gray to dull orange-brown.

Orange mock chanterelles are mostly found in higher elevations of the Pacific Northwest and parts of the Rocky Mountains. They grow in coniferous forests, often appearing after rainfall.

Some people report eating them without issues, but others experience stomach upset. The flavor is mild but not especially enjoyable.

Chanterelle Waxy Cap (Hygrocybe cantharellus)

This waxy cap species is small, orange to yellow, and often found in grassy fields or forest edges. It has widely spaced gills and a shiny, moist surface that can be confused with young chanterelles.

It’s more common in the eastern U.S., especially in the Southeast and Midwest during the warmer months. Unlike chanterelles, it thrives in open lawns, meadows, and disturbed soil.

While it is not toxic, it’s considered inedible due to its soft, watery texture and lack of flavor. Its fragile structure breaks down quickly after picking.

How to Find Chanterelles

Chanterelles don’t just grow anywhere. These mushrooms are tied to very specific forests, trees, and soil conditions. Once you learn how to read the land, you’ll start spotting the signs that indicate that chanterelles are likely nearby.

Before you head out, make sure you’re equipped with the right tools by checking out the ultimate forager’s toolkit.

Look Under Mature Hardwood Trees

Chanterelles grow in the ground beneath living trees, especially older hardwoods. In the eastern US, they are most often found under white oak, red oak, and American beech. These trees provide the stable root systems chanterelles need to form their underground mycorrhizal networks.

The best forests are ones that haven’t been logged or heavily disturbed for decades. Look for areas with a mostly closed canopy, scattered light, and a soft carpet of fallen leaves from previous seasons. Avoid young mixed forests with patchy cover or aggressive undergrowth.

Seek Out Mossy Forests with Douglas Fir and Hemlock

In certain places in the country, chanterelles grow in conifer forests dominated by Douglas fir, Sitka spruce, and western hemlock. They favor dense stands of older trees where the ground is covered with needles, moss, and woody debris.

Look in upland areas that stay moist but not wet, especially slopes or forest benches. Avoid low flood-prone areas or ridges that dry out quickly. The most productive patches are often in stands where tree age is consistent and the understory is sparse.

If you’re foraging in suburban greenbelts or wooded edges near neighborhoods, these tips on suburban foraging may help you find promising patches close to home.

Look on Slopes with Soft Soil and Good Leaf Litter

Chanterelles grow in loose, aerated soil that stays moist for days after rainfall but doesn’t turn soggy or compact. The best soil is loamy or sandy loam, with a soft texture and good leaf litter coverage.

You’ll often find them on sloped terrain where water moves through slowly without pooling. Check the uphill edges of stream drainages, old animal trails, or natural shelves on the side of a ridge. Rocky or clay-heavy soil usually means fewer or no chanterelles.

Focus on Cool, Shady Areas with Dense Tree Cover

These mushrooms thrive in shaded woods that stay cool and damp even during warm weather. Ideal spots are under thick canopy cover with limited sunlight hitting the ground during midday.

Moss, ferns, and even scattered patches of clubmoss or Indian cucumber root can be good indicators. If the air feels noticeably cooler and more humid than other parts of the forest, slow down and look closer. Avoid sunny openings, grass-covered clearings, or areas with dense shrubs.

You might also find other simple foods to forage in spring when you’re scouting for early signs of chanterelles.

Search Two to Three Days After a Soaking Rain

Chanterelles fruit after sustained rainfall followed by warm, humid nights. A steady soaking rain rather than short bursts or drizzle is what triggers them to push up through the soil.

Once the ground has been wet for two to three days, and nighttime lows stay above 55 degrees, check likely patches within 48 to 72 hours. Foggy mornings, overcast skies, and mild daytime temperatures in the 60s or 70s are all promising signs. Avoid hot, dry stretches or cold snaps that stall growth.

Keeping track of local conditions and having a system to harvest wild foods effectively makes a big difference during short fruiting windows.

Check Older Forests with Soft, Moist Organic Cover

Chanterelles prefer to grow in areas where the ground is covered with a soft, undisturbed layer of leaf litter or conifer needles. This natural mulch helps maintain consistent soil moisture and creates a stable surface for fruiting.

Forests with years of built-up organic matter tend to be more productive than recently disturbed areas. Avoid spots where the ground is bare, compacted, or covered in grass and brambles, which can signal poor conditions for chanterelles.

Search for Moss Growing at the Base of Mature Trees

Patches of moss are often a good sign, especially when growing near the base of mature trees or across soft, sloping ground. Moss helps retain humidity and indicates soil that holds moisture without being soggy.

Look for green moss around shallow roots, exposed tree bases, or near decomposing wood that still has structure. These microhabitats suggest just the right balance of shade, moisture, and airflow that chanterelles prefer.

Scan the Area Carefully for Other Mycorrhizal Mushrooms

Seeing other mushrooms in the area can be an important clue that the ecosystem is supporting underground fungal networks. Species like russulas, amanitas, or boletes often fruit in the same conditions as chanterelles.

While they don’t always grow together, their presence means the soil and tree relationship is active and healthy. If you notice several types of mushrooms fruiting near hardwoods or conifers after rain, slow down and scan the area carefully.

Many of the same areas also produce easy-to-identify wild roots and tubers during the same season.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

Where You Can Find Chanterelles

These are some of the best locations in the state where chanterelles have turned up:

Michaux State Forest

Michaux State Forest stretches across more than 85,000 acres of rugged ridges, dense woodland, and clear streams in south-central Pennsylvania. With that much space, it also holds a wide range of microhabitats where chanterelle mushrooms tend to thrive, especially during the summer months.

Along the Blueberry Trail near Caledonia State Park, the mix of oak and hemlock cover paired with steady moisture levels creates a strong potential for chanterelle growth. The trail weaves through shaded hollows with soft leaf litter and occasional seeps that can support flushes of mushrooms after rain.

Further west, around Long Pine Run Reservoir, you’ll find forested slopes with a mix of beech, birch, and mountain laurel. Chanterelles often appear along the less-traveled footpaths that skirt the water, especially where the terrain stays cool and damp.

Near Woodrow Road, the small streams feeding into Mountain Creek pass through deeply wooded terrain with just the kind of rich duff layer chanterelles favor. The forest here is quieter and less fragmented, giving the mushrooms time to fruit undisturbed beneath mature hardwoods.

Black Moshannon State Park

Black Moshannon State Park is home to one of the largest and best-preserved bog ecosystems in Pennsylvania. Once you’re off the boardwalks and into the forested uplands, several spots offer excellent conditions for chanterelle mushrooms to grow.

The Moss-Hanne Trail winds through mixed hardwood forests where red oaks, beech, and birch dominate the canopy. In the shadier sections of this trail, especially along gently sloping terrain with soft leaf litter, chanterelles are known to thrive during wetter months.

The area surrounding Black Moshannon Lake, particularly along the Beaver Road access trail, features pockets of mature woods that stay damp well into summer. Under the dense cover near the western coves of the lake, you’ll find soil rich with decaying organic matter—just the kind of environment chanterelles prefer.

Further west, the Sleepy Hollow Trail offers quiet, less-traveled stretches that cut through mossy groves and low ridges. Here, the terrain shifts between hemlock stands and hardwood patches, creating the kind of varied forest floor where chanterelles have a solid chance of showing up.

Hickory Run State Park

Hickory Run State Park is home to Boulder Field, a massive expanse of rocks left behind by ancient glacial movement. Just a few miles from that open, rugged terrain, you’ll find forested areas with the kind of leaf litter and mixed hardwood canopy that tend to support chanterelle growth.

The Fourth Run Trail passes through damp hollows and shaded woods where oak and beech trees dominate—ideal companions for chanterelles. Sections near the stream crossings often stay moist well into summer, especially after a good rain, and the mossy understory creates the kind of environment these mushrooms thrive in.

Along Shades of Death Trail, the ground softens underfoot with thick layers of leaf duff and ferns, and the air feels cooler beneath the dense canopy.

The stretch where the trail runs parallel to Sand Spring Run is particularly promising, with a gentle slope and scattered birches and hemlocks that create just the right amount of filtered light.

The area around Hawk Falls, especially along the trail that leads to the waterfall, has several pockets of mixed forest with deep shade and rich soil. Look past the hemlocks and rhododendrons, and you’ll find stretches of forest floor where chanterelles are known to pop up when the timing is right.

Ricketts Glen State Park

Ricketts Glen State Park is best known for its 22 named waterfalls, each tucked along the rocky ravines of the Falls Trail system. With that much flowing water, moss-covered rock, and thick canopy overhead, this park naturally creates the kind of environment where chanterelles have plenty of reasons to appear.

Along the Ganoga Glen section of the Falls Trail, the mix of hemlocks and oaks provides the kind of tree cover chanterelles tend to favor. The moist, shaded terrain between Ganoga Falls and Tuscarora Falls is especially promising during the wetter months.

Lake Rose Trail loops through dense mixed hardwood forest with gentle slopes and rich leaf litter—ideal terrain for spotting patches of golden caps in the summer. Several low-lying hollows just off the main path hold onto moisture even after dry spells, giving chanterelles a longer window to fruit.

To the north, the Cherry Run Trail passes through stretches of mature forest with well-drained soil and minimal foot traffic. This area gets a good balance of filtered sunlight and summer humidity, making it another spot worth checking for chanterelles when the conditions line up.

Colton Point State Park

Colton Point State Park is perched on the west rim of Pennsylvania’s Pine Creek Gorge, offering dramatic views from sheer cliffs that rise over 800 feet. Beyond the overlooks, the wooded interior of the park hides a much different kind of treasure in its damp hollows and shaded forest floor.

The Bohen Trail, winding through dense hardwoods and crossing several small creeks, is one of the most promising areas in the park for finding chanterelles.

Sections of this trail near its junction with Pine Creek are particularly rich in mossy ground cover and leaf litter beneath mature oak and beech trees—conditions that often support chanterelle growth.

Along Fourmile Run, a quiet stream that cuts through the southern end of the park, you’ll notice clusters of ferns and a dense canopy that keeps the forest floor cool and moist. The wooded banks here tend to hold onto moisture even in drier months, creating just the kind of microhabitat where chanterelles can thrive.

Another good spot is the area around Painter-Leetonia Road, especially where the road passes through thick groves of mixed hardwoods. The understory in this section stays relatively undisturbed, and when the soil is damp enough, chanterelles often make an appearance between patches of moss and fallen twigs.

Additional Locations to Find Chanterelles

These additional areas offer promising terrain for finding chanterelles in the state:

| North Central Pennsylvania | Chanterelle Collection Details |

| Colton Point State Park | Foraging for personal use only |

| Hammersley Wild Area | Foraging allowed, follow Leave No Trace |

| Johnson Run Natural Area | Allowed with caution to preserve habitat |

| Lebo Red Pine Natural Area | Foraging permitted on marked trails |

| Leonard Harrison State Park | No commercial foraging allowed |

| Lower Jerry Run Natural Area | Foraging for personal use only |

| Northeast Pennsylvania | Chanterelle Collection Details |

| Hickory Run State Park | Limited to berries and mushrooms |

| Kettle Creek Gorge Natural Area | No commercial foraging allowed |

| Ricketts Glen State Park | Permit required for foraging |

| Northwest Pennsylvania | Chanterelle Collection Details |

| Beaver Meadows Hiking Trail | Foraging allowed in designated areas |

| Cook Forest State Park | Common wild edibles allowed with limits |

| Pymatuning State Park | Foraging for personal use only |

| Central Pennsylvania | Chanterelle Collection Details |

| Bear Meadows Natural Area | Foraging discouraged in protected zones |

| Black Moshannon State Park | No commercial foraging allowed |

| Jakey Hollow Natural Area | Minimal-impact foraging permitted |

| Joyce Kilmer Natural Area | Foraging for personal use only |

| Little Juniata Natural Area | Foraging allowed, no soil disturbance |

| The Hook Natural Area | Personal use only, no digging permitted |

| Western Pennsylvania | Chanterelle Collection Details |

| Foraging Pittsburgh (Western PA) | Educational foraging walks available |

| McConnells Mill State Park | Foraging permitted with minimal impact |

| Moraine State Park | Limited foraging with park approval |

| South Central Pennsylvania | Chanterelle Collection Details |

| Horn Farm Center | Guided foraging classes only |

| Michaux State Forest | Foraging for personal use only |

| Southeast Pennsylvania | Chanterelle Collection Details |

| Happy Cat Farm Foraging School | Seasonal workshops, supervised foraging |

| Longwood Gardens | Foraging permitted only during events |

| Southwest Pennsylvania | Chanterelle Collection Details |

| Laurel Hill State Park | No commercial foraging allowed |

| Ohiopyle State Park | Foraging allowed, follow park rules |

When You Can Find Chanterelles

Chanterelles are one of the most prized wild mushrooms in North America, and knowing when to find them is just as important as knowing where they grow.

Their season depends heavily on rainfall, temperature, and the type of forest they grow in, which can vary across the United States. They often grow alongside other seasonal favorites like easy-to-identify wild fruits and berries, especially in wetter climates.

In the southeastern states, chanterelles often appear in early summer, especially after steady rains in May or June. They can continue fruiting through August or even into September in cooler, shaded areas. Southern Appalachian forests are known for producing long chanterelle seasons when the weather stays damp.

In the Midwest and Northeast, chanterelle season usually starts a little later. Most fruiting begins in late June or early July, following heavy summer storms. The season typically peaks in July and August, especially in mixed hardwood forests with plenty of leaf litter.

On the West Coast, the timing changes again. In California and the Pacific Northwest, chanterelles generally show up in the fall, especially after the first soaking rains of October or November. They can continue into January if the weather stays cool and wet.

Elevation also plays a role. In mountainous areas, you might find chanterelles at lower elevations early in the season, with higher elevation patches coming in a few weeks later. This can stretch the season out over several months if conditions are right.

The key is to track rainfall and watch local temperatures. Chanterelles thrive when the ground is moist but not soggy and the air is warm but not hot. If you pay attention to those patterns, you’ll start to notice the window when they reliably appear in your area.

While you’re planning your next outing, take a moment to read up on wild seeds, nuts, and berries that are easy to identify—they often grow in the same forest ecosystems.

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.