Hunting for chanterelle mushrooms in California can be a rewarding experience if you know when and where to go. These golden mushrooms flourish under just the right mix of moisture, tree cover, and elevation, and they often return to the same spots year after year.

Wild chanterelles have been part of the human diet for thousands of years. Foragers today still seek them with the same enthusiasm, drawn by their distinctive aroma and meaty texture. It’s easy to see why they’ve remained one of the most prized edible mushrooms throughout history.

The forests of California hide pockets of ideal habitat, but finding those places takes more than luck. If you know where to look and narrow down your search, you could end the day with a variety of mushrooms worth bragging about.

If you want to double up on the adventure and keep an eye out for valuable rocks and minerals while you’re out there, the only other thing you might want is Rock Chasing’s California Rocks & Minerals Identification Field Guide.

It helps you spot what’s worth picking up, and it keeps you from walking right past something special without realizing it.

What We Cover In This Article:

- What Chanterelle Mushrooms Look Like

- Mushrooms That Look Like Chanterelles But Aren’t

- How to Find Chanterelles

- Where You Can Find Chanterelles

- Additional Locations to Find Chanterelles

- When You Can Find Chanterelles

- The extensive local experience and understanding of our team

- Input from multiple local foragers and foraging groups

- The accessibility of the various locations

- Safety and potential hazards when collecting

- Private and public locations

- A desire to include locations for both experienced foragers and those who are just starting out

Using these weights we think we’ve put together the best list out there for just about any forager to be successful!

A Quick Reminder

Before we get into the specifics about where and how to find these plants and mushrooms, we want to be clear that before ingesting any wild plant or mushroom, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All plants and mushrooms have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming wild foragables, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging involves inherent risks.

What Chanterelle Mushrooms Look Like

Chanterelles are among the most popular wild edible mushrooms in North America. Here are some of the main types of chanterelles found across different regions of the country:

Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius group)

Golden chanterelles are one of the most recognizable wild mushrooms, with bright yellow to deep orange caps shaped like trumpets. They have thick, wavy edges and shallow ridges underneath instead of true gills.

These mushrooms are known for their fruity, apricot-like scent and a rich, nutty flavor when cooked. They grow in hardwood forests across the eastern, central, and southern United States, often near oaks, beech, or birch trees in late summer through fall.

Most people don’t realize how many incredible rocks California hides in its mountains, deserts, and beaches. This guide shows exactly what you’ve been walking past.

🌈 300+ color photos of real California specimens

🪨 Raw + polished examples make identification simple

🏜️ Covers coastlines, gold country, Sierras & more

💦 Waterproof pages built for real outdoor use

Pacific Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus formosus)

The Pacific golden chanterelle has a bright orange cap with a flared, uneven shape and shallow, blunt ridges underneath. Its sturdy stem is usually pale to light yellow, and the whole mushroom has a smooth, velvety feel.

It has a mild, nutty taste with a hint of fruitiness when cooked. These mushrooms are mostly found in the damp forests of Oregon, Washington, and northern California, often growing under Douglas fir and other conifers in fall and early winter.

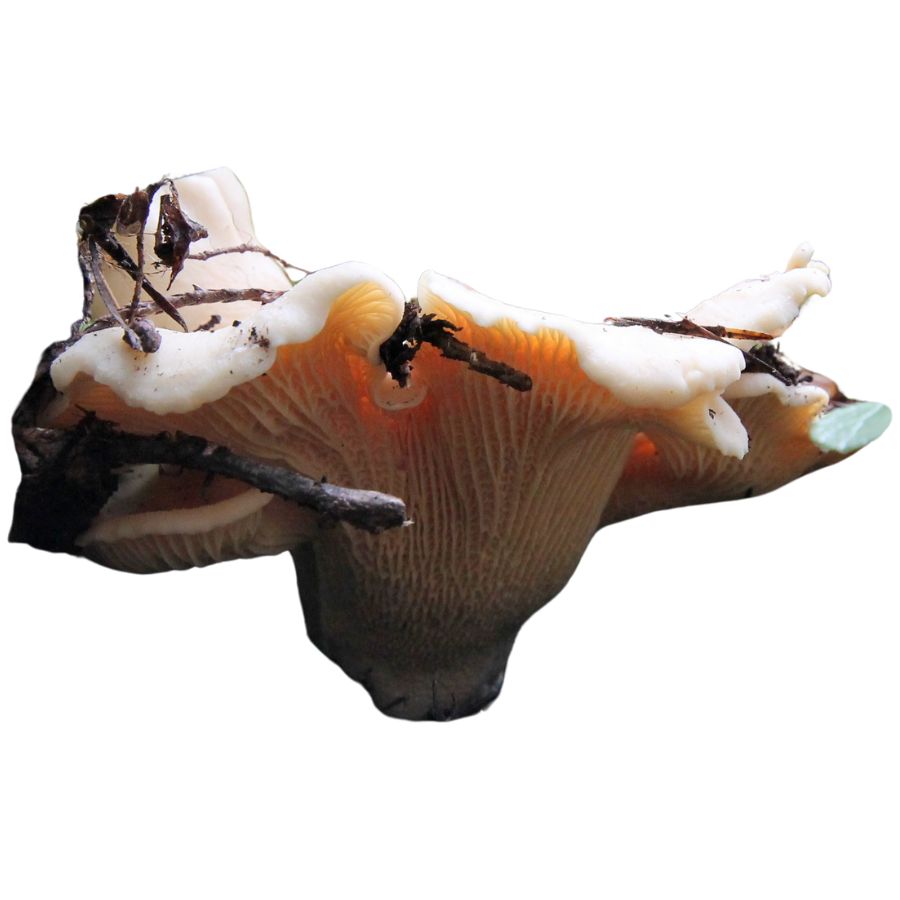

White Chanterelle (Cantharellus subalbidus)

White chanterelles are large, heavy mushrooms with a smooth, off-white cap that can look almost golden after rain. The stem is thick and solid, and the surface may feel slightly waxy when fresh.

They have a subtle earthy taste with a gentle, fruity smell that gets stronger in the pan. These mushrooms grow in moist conifer forests along the West Coast, especially in Oregon and northern California, often hiding under thick layers of fir needles.

Smooth Chanterelle (Cantharellus lateritius)

The smooth chanterelle has a soft orange to pale yellow cap with an almost completely smooth underside instead of well-defined ridges. Its cap often blends right into the stem, giving it a rounded, seamless appearance.

It has a mild, slightly peppery flavor and a firm texture when cooked. This mushroom is common in the eastern and southeastern United States, especially in hardwood forests with oak and beech during warm summer months.

Red Chanterelle (Cantharellus cinnabarinus)

Red chanterelles are easy to spot thanks to their vivid coral to crimson coloring and compact size. They have a smooth, wavy cap with soft ridges that flow down a short, sturdy stem.

Their taste is delicate and slightly sweet, with a faint fruity smell when fresh. These mushrooms grow in leaf litter across eastern and southeastern forests, often appearing in large groups during warm, wet periods in summer.

Mushrooms That Look Like Chanterelles But Aren’t

Chanterelles have several lookalikes that can confuse even experienced foragers. This is why learning to recognize easy-to-identify wild mushrooms is one of the most important skills for any mushroom hunter. Below are a few mushrooms often mistaken for chanterelles, with details on how to tell them apart.

False Chanterelle (Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca)

The false chanterelle has a bright orange to orange-brown cap with a fuzzy surface and rolled-in edges. Its gills are thin, crowded, and more regular than true chanterelles.

This mushroom shows up in many parts of the U.S., especially in conifer forests of the Pacific Northwest, the Northeast, and the Southeast. It prefers mossy or needle-covered forest floors and often grows on decaying wood.

While not dangerously toxic, it can cause stomach upset and isn’t considered a good edible. Its bitter taste and texture make it unappealing.

Jack-o’-Lantern Mushroom (Omphalotus illudens, Omphalotus olearius, Omphalotus subilludens)

These mushrooms are often bright orange, grow in clusters, and have true gills that run down the stem. They are best known for their eerie greenish glow at night due to bioluminescence.

Jack-o’-lantern mushrooms are found in hardwood forests throughout the eastern U.S., the Midwest, the Gulf Coast, and parts of California. They typically grow on decaying stumps or buried wood.

All three species are poisonous and can cause severe vomiting, cramps, and diarrhea. They should never be eaten under any circumstances.

Scaly Vase Chanterelle (Turbinellus floccosus)

This mushroom has a thick, vase-like shape with a scaly orange to brownish cap and ridged, wrinkled undersides. Unlike chanterelles, it has a tough texture and a strong, unpleasant odor when mature.

It’s widespread in western states like California, Oregon, and Washington, especially in conifer-heavy mountain forests. Scaly vase chanterelles often grow near pines or firs and appear in summer through fall.

While not deadly, they can cause nausea and gastrointestinal issues and are not considered edible. Their coarse texture and poor flavor also make them undesirable.

Orange Mock Chanterelle (Gomphus clavatus, sometimes called Pig’s Ears)

Despite its nickname, this mushroom is shaped more like a funnel or ear than a true chanterelle. Its surface is wrinkled rather than gilled, and the color ranges from lavender-gray to dull orange-brown.

Orange mock chanterelles are mostly found in higher elevations of the Pacific Northwest and parts of the Rocky Mountains. They grow in coniferous forests, often appearing after rainfall.

Some people report eating them without issues, but others experience stomach upset. The flavor is mild but not especially enjoyable.

Chanterelle Waxy Cap (Hygrocybe cantharellus)

This waxy cap species is small, orange to yellow, and often found in grassy fields or forest edges. It has widely spaced gills and a shiny, moist surface that can be confused with young chanterelles.

It’s more common in the eastern U.S., especially in the Southeast and Midwest during the warmer months. Unlike chanterelles, it thrives in open lawns, meadows, and disturbed soil.

While it is not toxic, it’s considered inedible due to its soft, watery texture and lack of flavor. Its fragile structure breaks down quickly after picking.

How to Find Chanterelles

Chanterelles don’t just grow anywhere. These mushrooms are tied to very specific forests, trees, and soil conditions. Once you learn how to read the land, you’ll start spotting the signs that indicate that chanterelles are likely nearby.

Before you head out, make sure you’re equipped with the right tools by checking out the ultimate forager’s toolkit.

Look Under Mature Hardwood Trees

Chanterelles grow in the ground beneath living trees, especially older hardwoods. In the eastern US, they are most often found under white oak, red oak, and American beech. These trees provide the stable root systems chanterelles need to form their underground mycorrhizal networks.

The best forests are ones that haven’t been logged or heavily disturbed for decades. Look for areas with a mostly closed canopy, scattered light, and a soft carpet of fallen leaves from previous seasons. Avoid young mixed forests with patchy cover or aggressive undergrowth.

Seek Out Mossy Forests with Douglas Fir and Hemlock

In certain places in the country, chanterelles grow in conifer forests dominated by Douglas fir, Sitka spruce, and western hemlock. They favor dense stands of older trees where the ground is covered with needles, moss, and woody debris.

Look in upland areas that stay moist but not wet, especially slopes or forest benches. Avoid low flood-prone areas or ridges that dry out quickly. The most productive patches are often in stands where tree age is consistent and the understory is sparse.

If you’re foraging in suburban greenbelts or wooded edges near neighborhoods, these tips on suburban foraging may help you find promising patches close to home.

Look on Slopes with Soft Soil and Good Leaf Litter

Chanterelles grow in loose, aerated soil that stays moist for days after rainfall but doesn’t turn soggy or compact. The best soil is loamy or sandy loam, with a soft texture and good leaf litter coverage.

You’ll often find them on sloped terrain where water moves through slowly without pooling. Check the uphill edges of stream drainages, old animal trails, or natural shelves on the side of a ridge. Rocky or clay-heavy soil usually means fewer or no chanterelles.

Focus on Cool, Shady Areas with Dense Tree Cover

These mushrooms thrive in shaded woods that stay cool and damp even during warm weather. Ideal spots are under thick canopy cover with limited sunlight hitting the ground during midday.

Moss, ferns, and even scattered patches of clubmoss or Indian cucumber root can be good indicators. If the air feels noticeably cooler and more humid than other parts of the forest, slow down and look closer. Avoid sunny openings, grass-covered clearings, or areas with dense shrubs.

You might also find other simple foods to forage in spring when you’re scouting for early signs of chanterelles.

Search Two to Three Days After a Soaking Rain

Chanterelles fruit after sustained rainfall followed by warm, humid nights. A steady soaking rain rather than short bursts or drizzle is what triggers them to push up through the soil.

Once the ground has been wet for two to three days, and nighttime lows stay above 55 degrees, check likely patches within 48 to 72 hours. Foggy mornings, overcast skies, and mild daytime temperatures in the 60s or 70s are all promising signs. Avoid hot, dry stretches or cold snaps that stall growth.

Keeping track of local conditions and having a system to harvest wild foods effectively makes a big difference during short fruiting windows.

Check Older Forests with Soft, Moist Organic Cover

Chanterelles prefer to grow in areas where the ground is covered with a soft, undisturbed layer of leaf litter or conifer needles. This natural mulch helps maintain consistent soil moisture and creates a stable surface for fruiting.

Forests with years of built-up organic matter tend to be more productive than recently disturbed areas. Avoid spots where the ground is bare, compacted, or covered in grass and brambles, which can signal poor conditions for chanterelles.

Search for Moss Growing at the Base of Mature Trees

Patches of moss are often a good sign, especially when growing near the base of mature trees or across soft, sloping ground. Moss helps retain humidity and indicates soil that holds moisture without being soggy.

Look for green moss around shallow roots, exposed tree bases, or near decomposing wood that still has structure. These microhabitats suggest just the right balance of shade, moisture, and airflow that chanterelles prefer.

Scan the Area Carefully for Other Mycorrhizal Mushrooms

Seeing other mushrooms in the area can be an important clue that the ecosystem is supporting underground fungal networks. Species like russulas, amanitas, or boletes often fruit in the same conditions as chanterelles.

While they don’t always grow together, their presence means the soil and tree relationship is active and healthy. If you notice several types of mushrooms fruiting near hardwoods or conifers after rain, slow down and scan the area carefully.

Many of the same areas also produce easy-to-identify wild roots and tubers during the same season.

Before you head out

Before embarking on any foraging activities, it is essential to understand and follow local laws and guidelines. Always confirm that you have permission to access any land and obtain permission from landowners if you are foraging on private property. Trespassing or foraging without permission is illegal and disrespectful.

For public lands, familiarize yourself with the foraging regulations, as some areas may restrict or prohibit the collection of mushrooms or other wild foods. These regulations and laws are frequently changing so always verify them before heading out to hunt. What we have listed below may be out of date and inaccurate as a result.

Where You Can Find Chanterelles

These are some of the best locations in the state where chanterelles have turned up:

Salt Point State Park

Salt Point State Park is home to one of California’s few underwater parks, where divers can explore a protected marine area just offshore. But inland, the forested parts of Salt Point hold their own surprises—especially when it comes to mushrooms.

The area surrounding the Central Trail is one of those places. This path runs through a dense mix of second-growth forest, and you’ll notice how the canopy lets in just enough light while keeping the ground soft and damp.

Chanterelles are known to emerge in good years along sections where the trail weaves between tanoak and fir, , especially when fallen leaves have built up in the low spots.

Another place that fits the bill is the forest around Phillips Gulch. If you head uphill just a bit, near where the rocks and roots start to dominate the trail edges, those are the kinds of microhabitats where chanterelles tend to thrive in this part of the park.

If your kids constantly ask “What’s this rock?”, this guide finally gives you an answer you don’t have to Google later. Quick photos, simple descriptions, and rugged pages make ID’ing rocks fun instead of frustrating.

🔍 Fast visual matching—no geology background needed

💦 Wipe-clean pages made for creeks, beaches & dirt

📚 Simple explanations for beginners of all ages

🌄 Great for California hikes, creek beds & camping trips

Sequoia National Park

Sequoia National Park is home to the largest tree on Earth by volume—General Sherman—a giant sequoia that towers over 275 feet tall and measures more than 36 feet across at the base. But beyond the famous trees and scenic vistas, parts of the park also offer excellent terrain for finding chanterelle mushrooms.

The mixed conifer and fir forests around Crescent Meadow, especially where the understory is thick with duff and the trail runs damp after rains, have the kind of conditions chanterelles thrive in.

You’ll also want to check the areas surrounding Marble Fork Kaweah River near Lodgepole. The forested stretches along the Tokopah Falls Trail are shaded and stay moist longer into the season, with enough plant debris to support fungal growth.

Further south, the higher-elevation woodlands along the Panther Gap Trail near Moro Rock offer another promising spot. This trail cuts through dense forest where leaf litter builds up on the slopes, and the terrain holds moisture well.

Lassen National Forest

Lassen National Forest is home to the southernmost volcano in the Cascade Range, and it last erupted in 1915. It’s one of the few places in California where you can explore a lava tube one day and hike through old-growth fir forests the next.

Near Butte Lake, the shaded sections of the Cinder Cone Trail weave through thick pine and fir woods that often hold onto moisture longer than the exposed lava beds nearby. These lower-lying areas just off the trail are surrounded by duff-covered ground that tends to support a good mix of fungal growth, including chanterelles.

Along Lost Creek, especially the segments near the Summit Lake area, the forest floor is dense with leaf litter from Douglas-firs and red firs. That stretch of forest sees regular summer storms and runoff from higher elevations, creating exactly the kind of moist, undisturbed environment chanterelles favor.

The Childs Meadow area just southwest of the forest boundary also contains several trails that wind through mixed conifer stands and seasonal seeps. Areas around Gurnsey Creek and the adjacent forest slopes are also particularly promising.

Los Padres National Forest

Los Padres National Forest contains one of the longest stretches of protected coastline in California, along with pockets of surprisingly lush forest. One of those pockets sits in the canyons near Arroyo Seco, where a mix of oaks and sycamores offers the kind terrain where chanterelle mushrooms tend to grow.

Big Pine Mountain supports one of the only true subalpine environments in the southern half of the forest. Around Madulce Peak and the upper forks of Santa Barbara Creek, the blend of fir, pine, and hardwoods provides peak conditions for chanterelles.

Nacimiento-Fergusson Road winds from inland valleys to sweeping ocean views, crossing one of the most botanically diverse gradients in the forest. In the forests surrounding San Antonio River and Baldwin Creek, chanterelles often grow in moist pockets beneath tanoak and madrone near seasonal seeps.

The Ventana Wilderness holds some of the most rugged terrain in California, with deep canyons accessible only by foot. Along the Pine Ridge Trail near Tassajara Creek, chanterelles are known to emerge beneath Douglas-fir and oak in the cool, mist-fed understory.

Shasta-Trinity National Forest

Shasta-Trinity National Forest is the largest national forest in California, stretching across rugged terrain from Mount Shasta down to the Trinity Alps. Within its millions of acres, several pockets offer the kind of conditions where chanterelle mushrooms are likely to grow, especially in the cooler, wetter months.

On the eastern side near Castle Crags, the Root Creek Trail cuts through a deep, shaded ravine fed by spring runoff and lined with fir and oak. The mix of leaf litter and steady moisture here creates a promising zone for chanterelles, especially where the trail crosses beneath thicker canopy.

Farther west, the forest surrounding Trinity Lake holds a wide range of habitats, but the Coffee Creek drainage stands out. Its side streams, like East Fork Coffee Creek—are surrounded by mature conifers and duff-covered slopes, giving chanterelles plenty of space to thrive in late fall.

To the south, in the Trinity Alps Wilderness section of the forest, the Stuart Fork Trail leads you through high-elevation conifer stands and past Sapphire Lake. Around the lower switchbacks and creek-fed valleys, chanterelles are often found where tanoak and Douglas-fir dominate the hillsides.

Additional Locations to Find Chanterelles

If you’re looking to explore even more ground, these additional locations across the state are also worth checking:

| Bay Area | Chanterelle Collection Details |

| Point Reyes National Seashore | Foraging permitted in designated zones |

| Central Coast | Chanterelle Collection Details |

| Los Padres National Forest | Personal-use foraging allowed |

| North Coast | Chanterelle Collection Details |

| Jackson Demonstration State Forest | Permit required for foraging |

| Mendocino National Forest | Foraging allowed with seasonal limits |

| Redwood National and State Parks | No commercial foraging allowed |

| Salt Point State Park | Foraging for personal use only |

| Six Rivers National Forest | Limited foraging with local restrictions |

| Sierra Nevada | Chanterelle Collection Details |

| Eldorado National Forest | Personal foraging allowed, no sales |

| Klamath National Forest | Foraging permitted, some permits needed |

| Lassen National Forest | Non-commercial foraging allowed |

| Modoc National Forest | Limited personal-use foraging allowed |

| Plumas National Forest | Foraging permitted with caution |

| Shasta-Trinity National Forest | Foraging allowed in many areas |

| Sierra National Forest | Small-scale foraging permitted |

| Stanislaus National Forest | Foraging requires adherence to guidelines |

| Tahoe National Forest | Foraging allowed with some restrictions |

| Kings Canyon National Park | Personal-use foraging permitted with restrictions |

| Sequoia National Park | Small-scale foraging for personal use is allowed |

| Southern California | Chanterelle Collection Details |

| Angeles National Forest | Recreational foraging allowed |

When You Can Find Chanterelles

Chanterelles are one of the most prized wild mushrooms in North America, and knowing when to find them is just as important as knowing where they grow.

Their season depends heavily on rainfall, temperature, and the type of forest they grow in, which can vary across the United States. They often grow alongside other seasonal favorites like easy-to-identify wild fruits and berries, especially in wetter climates.

In the southeastern states, chanterelles often appear in early summer, especially after steady rains in May or June. They can continue fruiting through August or even into September in cooler, shaded areas. Southern Appalachian forests are known for producing long chanterelle seasons when the weather stays damp.

In the Midwest and Northeast, chanterelle season usually starts a little later. Most fruiting begins in late June or early July, following heavy summer storms. The season typically peaks in July and August, especially in mixed hardwood forests with plenty of leaf litter.

On the West Coast, the timing changes again. In California and the Pacific Northwest, chanterelles generally show up in the fall, especially after the first soaking rains of October or November. They can continue into January if the weather stays cool and wet.

Elevation also plays a role. In mountainous areas, you might find chanterelles at lower elevations early in the season, with higher elevation patches coming in a few weeks later. This can stretch the season out over several months if conditions are right.

The key is to track rainfall and watch local temperatures. Chanterelles thrive when the ground is moist but not soggy and the air is warm but not hot. If you pay attention to those patterns, you’ll start to notice the window when they reliably appear in your area.

While you’re planning your next outing, take a moment to read up on wild seeds, nuts, and berries that are easy to identify—they often grow in the same forest ecosystems.

One Final Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only. Foraging for wild plants and mushrooms involves inherent risks. Some wild plants and mushrooms are toxic and can be easily mistaken for edible varieties.

Before ingesting anything, it should be identified with 100% certainty as edible by someone qualified and experienced in mushroom and plant identification, such as a professional mycologist or an expert forager. Misidentification can lead to serious illness or death.

All mushrooms and plants have the potential to cause severe adverse reactions in certain individuals, even death. If you are consuming foraged items, it is crucial to cook them thoroughly and properly and only eat a small portion to test for personal tolerance. Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to specific mushrooms and plants, even if they are considered safe for others.

Foraged items should always be fully cooked with proper instructions to ensure they are safe to eat. Many wild mushrooms and plants contain toxins and compounds that can be harmful if ingested.